Sovereign citizen movement

The sovereign citizen movement (also SovCit movement or SovCits)[1] is a loose group of anti-government activists, vexatious litigants, tax protesters, financial scammers, and conspiracy theorists based mainly in the United States. Sovereign citizens have their own pseudolegal belief system based on misinterpretations of common law and claim not to be subject to any government statutes unless they consent to them.[2][3] The movement appeared in the U.S. in the early 1970s and has since expanded to other countries; the similar freeman on the land movement emerged during the 2000s in Canada before spreading to other Commonwealth countries such as Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.[4] The FBI has called sovereign citizens "anti-government extremists who believe that even though they physically reside in this country, they are separate or 'sovereign' from the United States".[5]

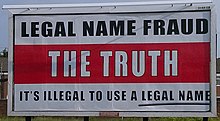

The sovereign citizen phenomenon is one of the main contemporary sources of pseudolaw. Sovereign citizens believe that courts have no jurisdiction over people and that certain procedures (such as writing specific phrases on bills they do not want to pay) and loopholes can make one immune to government laws and regulations.[6] They also regard most forms of taxation as illegitimate and reject Social Security numbers, driver's licenses, and vehicle registration.[7] The movement may appeal to people facing financial or legal difficulties or wishing to resist perceived government oppression. As a result, it has grown significantly during times of economic or social crisis.[8] Most schemes sovereign citizens promote aim to avoid paying taxes, ignore laws, eliminate debts, or extract money from the government.[3] Sovereign citizen arguments have no basis in law and have never been successful in any court.[3][6]

American sovereign citizens claim that the United States federal government is illegitimate.[3][9] Sovereign citizens outside the U.S. hold similar beliefs about their countries' governments. The movement can be traced to American far-right groups such as the Posse Comitatus and the constitutionalist wing of the militia movement.[10] The sovereign citizen movement was originally associated with white supremacism and antisemitism, but now attracts people of various ethnicities, including a significant number of African Americans.[3] The latter sometimes belong to self-declared Moorish sects.[11]

The majority of sovereign citizens are not violent.[2][12] But the methods the movement advocates are illegal. Sovereign citizens notably adhere to the fraudulent schemes promoted by the redemption "A4V" movement. Many sovereign citizens have been found guilty of offenses such as tax evasion, hostile possession, forgery, threatening public officials, bank fraud, and traffic violations.[3][5][13] Two of the most important crackdowns by U.S. authorities on sovereign citizen organizations were the 1996 case of the Montana Freemen and the 2018 sentencing of self-proclaimed judge Bruce Doucette and his associates.[14]

Because some have engaged in armed confrontations with law enforcement,[2][15] the FBI classifies "sovereign citizen extremists" as domestic terrorists.[16] Terry Nichols, one of the perpetrators of the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, subscribed to a variation of sovereign citizen ideology.[13] In surveys conducted in 2014 and 2015, representatives of U.S. law enforcement ranked the risk of terrorism from the sovereign citizen movement higher than the risk from any other group, including Islamic extremists, militias, racist skinheads, neo-Nazis, and radical environmentalists.[17][18] In 2015, the Australian New South Wales Police Force identified sovereign citizens as a potential terrorist threat.[19]

History

Origin

The sovereign citizen movement originated from a combination of tax protester ideas, from the radical and racist anti-government movements in the 1960s and 1970s,[20] and pseudolaw, which has existed in the U.S. since at least the 1950s.[6] Their belief in the illegitimacy of federal income tax gradually expanded to challenging the legitimacy of the government.[3]

The concept of a "sovereign citizen" whose rights are unfairly denied appeared in 1971 within the Posse Comitatus as a teaching of Christian Identity minister William Potter Gale.[3][9] The Posse Comitatus was a far-right anti-government movement[3] that denounced the income tax, debt-based currency, and debt collection as tools of Jewish control over the United States.[21] The roots of the sovereign citizen movement were thus strongly associated with white supremacist and antisemitic ideologies.[3][9] Gale's racist beliefs were far from unique, but he innovated by devising a "legal" philosophy about the illegitimacy of the government that appealed to disaffected people.[9]

After originating in that particular group, the sovereign citizen concept went on to influence the broader tax protester and Christian Patriot movements.[3][9] Until the 1990s, observers mainly classified the Posse Comitatus as a tax protester movement rather than an outright far-right extremist group. But while the Posse Comitatus, Christian Identity, and militia movements did not entirely merge with each other, there was significant overlap between them.[22]

Developments

In the early 1980s, Gordon Kahl, a former Posse Comitatus member, helped radicalize sovereign citizen anti-government rhetoric. Kahl considered the government not only illegitimate but actively hostile to Americans' interests. After Kahl was killed in 1983 during a shootout with law enforcement, the movement considered him a martyr, which helped disseminate his views.[22]

The movement garnered more support during the American farm crisis of the late 1970s and 1980s, which coincided with a general financial crisis in the U.S. and Canada.[20] The farm crisis saw the rise of anti-government protesters selling fraudulent debt relief programs,[23] some of whom were associated with far-right groups. They included Roger Elvick,[24] a member of a successor organization of the Posse Comitatus. Elvick conceived the redemption methods, a set of fraudulent debt and tax payment schemes[25] that became part of sovereign citizen ideology.[26]

As the Posse Comitatus movement evolved, its members created pseudolegal bodies that claimed to speak with the authority of "natural law" or "common law" and to supersede the government's legal system. The most common tactic of these "common law courts" was to issue false liens against their enemies' property.[22]

After the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, one perpetrator of which adhered to sovereign citizen ideology, observers categorized the Posse Comitatus as far-right extremism rather than a tax protester movement. Around the end of the decade, the term "Posse Comitatus" was supplanted by the term "sovereign citizen". This mirrored a change in the language adherents used, which reflected their increased focus on personal liberty secured through absolute ownership of personal property.[22]

In 1996, the case of the Montana Freemen attracted public attention to the sovereign citizen movement. The Montana Freemen were Christian Patriot sovereign citizens and direct ideological descendants of the Posse Comitatus:[9] they used false liens to harass public officials[27] and committed bank fraud with counterfeit checks and money orders.[28] The group surrendered in June 1996 after 81 days of armed standoff with the FBI.[29] Several members of the Montana Freemen received long prison sentences. The group's leader, LeRoy M. Schweitzer, died in prison in 2011.[30]

Over time, the movement expanded beyond its original white nationalist environment to people of all backgrounds.[31] By the 1990s, sovereign citizen arguments had been adopted by minority groups, notably the African American Moorish sovereigns.[11][32] The Moorish sovereigns' beliefs derive, in part, from the Moorish Science Temple of America, which has condemned this sovereign citizen offshoot.[11]

Since the 1990s, the number of African American sovereign citizens has increased substantially. Various Black sovereign citizen groups have appeared, some Islamic, others adhering to New Age philosophies.[13] Sovereign citizen ideas have also been adopted by some groups within the Hawaiian sovereignty movement[2] and various other fringe political or religious groups, such as black separatists or the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints.[13]

American pseudolaw became well-established by 2000. Notably, Elvick conceived the strawman theory around that time; it became a core sovereign citizen concept, as it gave an overarching explanation to the movement's pseudolegal beliefs.[6]

Spread

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, sovereign citizen ideology was introduced into Canada and then gradually into other countries[6] as the advent of the Internet facilitated communication between people sharing the same ideas.[20] One influential American "guru" who helped spread sovereign citizen ideology abroad was Winston Shrout, who held seminars in Canada (until he was banned from the country), Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.[33]

In Canada, sovereign citizen beliefs mixed with local tax protester concepts during the 2000s and gave birth to an offshoot, the freeman on the land movement, which eventually spread to other Commonwealth countries.[34]

Since the late 2000s, the sovereign citizen movement has significantly expanded in the U.S. due to the Great Recession and more specifically the mortgage crisis.[34][22][35][36] In 2010, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) estimated that 100,000 Americans were "hard-core sovereign believers", with another 200,000 "just starting out by testing sovereign techniques for resisting everything from speeding tickets to drug charges".[37] According to another SPLC estimate, the number of sovereign citizen-influenced militia groups in the U.S. increased dramatically between 2008 and 2011, from 149 to 1,274.[15]

Incidents such as the 2003 Abbeville standoff, the 2007 Edward and Elaine Brown standoff, the 2010 West Memphis police shootings, the 2014 Bundy standoff, the 2016 Malheur Refuge occupation (also involving the Bundy family), the 2016 Baton Rouge police shootings, and the 2021 Wakefield standoff (involving African-American Moorish sovereign citizens) attracted significant media attention. In 2022, the trial of the Waukesha Christmas parade attack's perpetrator brought the movement further attention, as the defendant used sovereign citizen arguments during the proceedings.[38]

The sovereign citizen and QAnon movements overlap.[3] A sovereign citizen group known as the Oath Enforcers attracted QAnon and Donald Trump supporters into the movement after the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol.[39] In 2022, the Anti-Defamation League reported that the sovereign citizen movement was attracting a growing number of QAnon adherents, whose belief in the illegitimacy of the Biden administration is compatible with the sovereign citizens' broader anti-government views.[40]

Videos of people attempting to use sovereign citizen-style arguments during traffic stops, in courtrooms, and in other public places are common on the Internet, where they are often considered a source of amusement. Researcher Christine Sarteschi has said that this may cause people to underestimate the movement's potential for violence and its links with criminal conduct. Several people charged with crimes such as murder or sexual assault have used sovereign citizen arguments as attempts to negate the court's jurisdiction over them.[41]

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the movement's spread. Sovereign citizens have been associated with the broader anti-mask and anti-vaccine movements and taken part in anti‐restriction protests.[42][43][44] An increase in sovereign citizens has been observed in Australia and the United Kingdom during the pandemic.[44][45][46] Several COVID-related incidents involving local sovereign citizens who refused to follow sanitary measures were also reported in Singapore.[47][48] In June 2022, Sarteschi reported that the movement was rapidly expanding and could now be found in 26 countries.[49]

Government response

After the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, U.S. federal law enforcement began cracking down on white supremacist groups, including sovereign citizen organizations. The Montana Freemen incident occurred in that context.[9] The bombing also led Congress to pass the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, enhancing sentences for certain terrorism-related offenses.[50]

Hundreds, if not thousands, of sovereign citizens have been imprisoned as a result of their actions. Many have continued their activities behind bars, often spreading their ideologies among other inmates.[13]

As of the 1990s, several hundred people involved in "common law courts" operated by sovereign citizens or, more broadly, by the Patriot movement have been arrested for crimes such as fraud, impersonating police, intimidating or threatening officials, and in some cases, outright violence. In 1998, a number of U.S. states passed laws outlawing the activities of these "courts" or strengthening existing sanctions.[51]

To prevent their courts from being burdened by frivolous litigation, some states have heightened penalties for people who file baseless motions. Some courts choose to impose pre-filing injunctions against certain pro se serial litigants, to preclude them from filing new lawsuits or documents without prior leave.[8]

After incidents such as the 2010 West Memphis police shootings, U.S. law enforcement agencies advised officers on how to deal with sovereign citizens at traffic stops and elsewhere.[52][53]

In Australia, after the 2022 Wieambilla shootings, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation and the Australian Federal Police indicated they would examine the groups more closely as their beliefs increasingly align with that of other extremists, with the AFP Joint Counter Terrorism Team now required to undergo training on sovereign citizen threats.[54][55]

Denominations and symbols

Not all members of the movement call themselves "sovereign citizens", and some regard the term as an oxymoron.[31] Sovereign citizens may prefer to call themselves "state nationals",[57] "constitutionalists", "freemen",[58] "natural people", "living people",[1] "private persons",[59] or people "seeking the truth"[60] or "living on the land".[59] The name "American State National"[40] (ASN) became popular among sovereign citizens in the early 2020s, especially among followers of the QAnon conspiracy theory.[61]

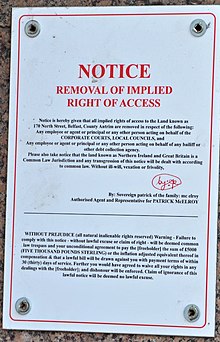

The sovereign citizen movement has no single universally accepted symbol or emblem, but sovereign citizen documents and signs often have distinctive identifying marks. Some of the most common ones are postage stamps and thumbprints on documents, and the addition of punctuation (dashes, hyphens, colons or commas) to one's name, which sovereign citizens believe has a legal effect.[56]

Groups such as Moorish sovereigns and the Washitaw Nation have their own specific flags and symbols. Some sovereign citizens use references to nonexistent "Republics" or to the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), variations on the flag of the United States, or religious symbols such as that of the Vatican, which are thought to establish "sovereignty".[62]

One common symbol of the American sovereign citizen movement is a version of the U.S. flag with alternate colors and vertical stripes. Sometimes known as "the flag of peace" or "Title Four flag", it is based on a flag allegedly used by American custom houses for a brief period during the 19th century. Around the 2000s, some sovereign citizens began to claim that this is the true flag of the United States.[56]

Theories

| Part of the Taxation in the United States series |

| Tax protest in the United States |

|---|

|

| History |

| Arguments |

| People |

| Related topics |

The movement has no defining text, established doctrine, or centralized leadership,[8][63] but there are common themes, generally implying that the legitimate government and legal system have been somehow replaced and that the current authorities are illegitimate. Taxes and licenses are likewise thought to be illegitimate. A number of leaders, commonly called "gurus", develop their own variations.[8][34] The movement's theories include influences from a variety of sources, some of them decades old, resulting in often confusing and incoherent narratives of U.S. history.[64]

Sovereign citizens' legal theories reinterpret the Constitution of the United States through selective reading of law dictionaries (notably an obsolete version of Black's Law Dictionary), state court opinions, or specific capitalization, and incorporate other details from a variety of sources, including the Uniform Commercial Code, the Articles of Confederation, the Magna Carta, the Bible, and foreign treaties. They ignore the second clause of Article VI of the Constitution (the Supremacy Clause), which establishes the Constitution as the law of the land and the United States Supreme Court as the ultimate authority to interpret it.[65][66][67] Most consider county sheriffs the most powerful law enforcement officers in the country, with authority superior to that of any federal agent, elected official, or other local law enforcement official.[68]

Illegitimacy of laws and government

A widespread belief among sovereign citizens is that the state is not an actual government, but a corporation. American movement members believe that the corporation that purports to be the U.S. federal government is illegally controlling the republic via a territorial government in Washington, D.C.[57]

Sovereign citizens believe that sometime after the Founding Fathers set up the government, commercial law secretly replaced common law. This commercial law is generally understood to be admiralty law, as sovereign citizens believe the current, illegitimate law is based on principles of international commerce.[64][3] Sovereign citizens also claim that the gold fringes on U.S. flags displayed in courtrooms is evidence that admiralty law is in effect.[26] This leads them to believe that U.S. judges and lawyers are actually agents of a foreign power,[3] typically thought to be the United Kingdom: one pseudolegal conspiracy theory claims that bar is an acronym for "British Accreditation Registry".[61]

Sovereign citizens therefore challenge the validity of the contemporary legal system and claim to answer only to God's law or to common law, by which they mean the system that supposedly existed before the conspiracy.[2]

There is no consensus among sovereign citizens as to when the secret change of the political and legal system took place; some believe it was during the Civil War, while others date it to 1933, when the U.S. abandoned the gold standard.[3] According to one version, the vehicle for the change was the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1871, which sovereign citizens believe created a "United States corporation" to govern the District of Columbia under commercial code; this form of corporate rule then extended to the entire country.[64] Another theory has it that the country was secretly reorganized as a post office in 1789.[69] Pseudolegal schemes attribute a particular power to the Universal Postal Union[70] and to the use of postage stamps on legal documents.[69][70]

The beliefs that the government is a corporation and that people are secretly under a form of commercial law leads sovereign citizens to believe that statutory law is a contract binding people to the state. According to this theory, people are tricked into this contract by various methods, including Social Security numbers, fishing licenses, or ZIP Codes: thus, avoiding their use means immunity from government authority.[71][72][31][73] Another common belief among sovereign citizens is that they can opt out of the purported contract, making themselves immune from the laws they do not wish to follow, by declining to "consent": when confronted by police officers or other officials, sovereign citizens typically attempt to negate their authority by saying, "I do not consent".[1]

Many sovereign citizens believe that the Uniform Commercial Code, which provides an interstate standard for documents that they believe apply only to their straw man, is a codification of the illegitimate commercial law ruling the United States. Therefore, they think that exploiting supposed loopholes in the UCC will help them assert their rights or invoke their special privileges and powers as "common law citizens".[64]

Adherents of the "American State National" concept believe that, through a specific procedure, they can renounce federal citizenship, make themselves immune from jurisdiction and arrest, avoid the IRS, and rescind voting registrations, marriages, or birth certificates. In March 2023, Chase Allan, a man who subscribed to this notion and used a false passport and an illegal license plate, was shot dead by police at a traffic stop in Utah during a confrontation with officers over his refusal to show an identification document.[61]

The belief that the current legal system is illegitimate has led some sovereign citizens to consider themselves "above the law" and commit crimes.[41]

Citizenship

American sovereign citizens posit that contemporary United States citizenship is somehow defective or fraudulent and that it curtails citizens' legitimate rights. Some sovereign citizens also claim that they can become immune to most or all laws of the United States by renouncing citizenship in a "federal corporation" and declaring themselves citizens only of the state where they reside: this process, which they call "expatriation", involves filing or delivering a nonlegal document claiming their renunciation of citizenship to any county clerk's office that can be convinced to accept it.[74]

In the 1970s, one of the movement's originators, white supremacist ideologue William Potter Gale, identified the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution as the act that converted "sovereign citizens" into "federal citizens" by their agreement to a contract to accept benefits from the federal government. Other commentators have identified other acts, including the Emergency Banking Act,[75] and the alleged suppression of the Titles of Nobility Amendment.[76]

Likewise, sovereign citizen leader Richard McDonald claimed that there are two classes of citizens in the U.S.: the "original citizens of the states" (also called "states citizens" or "organic citizens")[77] and "U.S. citizens". According to McDonald, U.S. citizens, whom he calls "Fourteenth Amendment citizens", have civil rights, legislated to give the rights to freed black slaves after the Civil War: this benefit is received by consent in exchange for freedom. On the other hand, white state citizens have unalienable constitutional rights. On this view, state citizens must take steps to revoke and rescind their U.S. citizenship and reassert their de jure common-law state citizen status. This involves removing oneself from federal jurisdiction and relinquishing any evidence of consent to U.S. citizenship, such as a Social Security number, driver's license, car registration, ZIP Code, marriage license, voter registration, or birth certificate. Also included is the refusal to pay state and federal income taxes because citizens not under U.S. jurisdiction are not required to pay them.[78]

The concept of "14th Amendment citizens" is consistent with the movement's white supremacist origins in that it can cause adherents to believe that African Americans, having become citizens only after the Civil War, have far fewer rights than Whites,[77] or that only Black people have to pay federal taxes and abide by federal laws.[57]

On the contrary, "Moorish" sovereign citizens think that African Americans constitute an elite class within American society, with special rights and privileges that make them immune from federal and state authority. They commonly adopt "Africanized" version of their names by adding "el", "Bey", or a combination of the two, and associate themselves with a particular "Moorish" group, claiming they are not culpable for acts committed under their former name and that their affiliation makes them immune to prosecution.[11][79] The underpinnings of their theories of exemption vary. One belief is that the "Moors" were America's original inhabitants and are therefore entitled to be self-governing. They claim to be descendants of the Moroccan "Moors" and thus subject to the 1786 Moroccan-American Treaty of Friendship, which they believe gives them exemption from U.S. law. A variation of "Moorish" ideology is found in the Washitaw Nation, which claims rights through provisions in the Louisiana Purchase treaty granting privileges to Moors as early colonists and the nonexistent "United Nations Indigenous People's Seat 215".[11] Various other groups claim special status and exemption from their countries' laws by purporting to belong to real or imaginary ethnic minorities.[13]

Sovereign citizens may claim that their status in the United States is that of "non-resident aliens".[77] Only residents (resident aliens) of the states, not its citizens, are income-taxable, sovereign citizens argue. And as a state citizen landowner, one can bring forward the original land patent and file it with the county for absolute or allodial property rights. Such allodial ownership is held "without recognizing any superior to whom any duty is due on account thereof" (Black's Law Dictionary). Superiors include those who levy property taxes or who hold mortgages or liens against the property.[78]

Dual personas

One recurring idea in sovereign citizen ideology is that individuals have two personas, one of flesh and blood and the other a separate, secret, legal personality (commonly called the "straw man"), created upon each person's birth, which is subject to the government. Sovereign citizens claim it is possible to dissociate oneself from the "straw man" by certain procedures, thus becoming free of all debts, liabilities and legal constraints.[6][10][26][69]

Economics

Sovereign citizen texts often posit that "international bankers" are at the source of the conspiracy that replaced the United States' legitimate government and legal system. In the movement's earlier form, these bankers were explicitly said to be Jews. While this can still be implied in sovereign citizen literature, the movement's original antisemitic conspiracy theories were diluted over time; most contemporary sovereign citizens tend to present greatly simplified versions of them, with no mention of Jewish conspiracies and only vague references to corrupt bankers.[64]

Some sovereign citizens believe that the United States "corporation" is bankrupt. This is often attributed to the 1933 abandonment of the gold standard.[64] As a result, the illegitimate U.S. government is said to secretly use its citizens as collateral against foreign debt, effectively enslaving Americans. Sovereign citizens believe that this sale of American citizens takes place at birth, through the issuance of birth certificates and Social Security numbers.[3][64][69]

The sovereign citizen movement overlaps with the redemption movement (also known as "A4V" after one of its schemes), which claims that a secret bank account is created for every citizen at birth as part of the process whereby the U.S. government uses its citizens as collateral.[70][69] Several prominent sovereign citizens have advocated redemption schemes.[13] The belief in a secret bank account is intertwined with the strawman theory, since each person's fund is supposedly associated with their "straw man".[13][64]

"Redemption" theories assert that the vast sums of money in this account can be reclaimed through certain procedures, and applied to financial obligations or even criminal charges.[70][69] In some variations of this theory, the secret fund may be called a "Cestui Que Vie Trust".[61]

Pseudolegal economic theories also imply various misconceptions about currencies and financial institutions, one being that banks "create money from thin air" so a borrower has no obligation to pay them back, and another that money is actually worthless when not backed by gold.[6] Many sovereign citizens do not recognize U.S. currency and demand to receive payments in the form of gold or silver coins.[80][81][82]

Some sovereign citizens also subscribe to the NESARA-related conspiracy theory.[3]

Freedom of movement

Using arguments that rely on exacting definitions and word choice, sovereign citizens may assert a constitutional "right to travel" in a "conveyance", distinguishing it from driving an automobile in order to justify ignoring requirements for license plates, vehicle registration, insurances, and driver's licenses. The right to travel is claimed based on a variety of passages.[13][63][65]

One common argument of sovereign citizens is that they are "traveling" and not "driving" and hence do not need a driver's license because they are not transporting commercial goods or paying passengers.[3]

Other

Other pseudolegal theories commonly shared by sovereign citizens include that "silence means consent" for any sort of documents, that any claim or alleged statement of fact placed in a sworn document (known in pseudolegal jargon as an "affidavit of truth") is proven true unless rebutted, and that there is no crime if there is no injured party.[6]

Some sovereign citizens are involved in other forms of conspiracy theories, including QAnon.[83] Certain subgroups ofs the movement adhere to theories about extraterrestrials and reptilians.[3] One advocate of sovereign citizen fraudulent tax avoidance schemes, Sean David Morton, was also active as a psychic and ufologist.[84] In Quebec, sovereign citizen ideology has been promoted by Guylaine Lanctôt, an anti-vaccine activist and AIDS denialist.[85]

In 2022, the Anti-Defamation League reported that sovereign citizen ideology was "increasingly seeping" into QAnon, as the movement's anti-government views were compatible with QAnon's belief in a worldwide "cabal" and in the illegitimacy of the Biden administration.[40]

Sovereign citizen groups, notably that led in Texas by "gurus" David and Bonnie Straight, a married couple, have been convincing parents whose children were removed from their custody that Child Protective Services engages in child trafficking, and encouraging them to kidnap their children.[41][86][61] The belief that child protection agencies are involved in crimes against children is also consistent with QAnon ideology.[61]

Several sovereign citizen "gurus" have made grandiose claims about the powers granted to them by their pseudolegal schemes. One American ideologue and "Quantum Grammar" advocate, Russell Jay Gould, claims that having signed a postal receipt in a specific way and filed a document relating to Title 4 of the United States Code, at a moment when the country was supposedly bankrupt, makes him the "Postmaster-General" and legitimate ruler of the United States.[32] Another American guru, Heather Ann Tucci-Jarraf, claimed before her sentencing for fraud to have "foreclosed" and "canceled" all banks and governments through UCC filings.[87] Likewise, Romana Didulo, a Canadian QAnon conspiracy theorist, uses sovereign citizen concepts to back her claims of being the rightful Queen of Canada, and eventually the "Queen of the World".[49][88][89]

Tactics

Sovereign citizens may be affiliated with a group within the movement, follow the teachings of a specific "guru", or act entirely on their own. By disobeying rules they consider illegitimate, they regularly find themselves in conflict with all forms of government institutions, most commonly law enforcement, the judiciary, and the revenue services.[13] One sovereign citizen from Montana, Ernie Wayne terTelgte, became a local celebrity in 2013 by engaging in a protracted legal battle with authorities over the need to have a fishing license[90] and then having multiple conflicts with law enforcement over this matter, as well as his lack of a driver's license.[91]

Sovereign citizens often use flawed or invented legal arguments or irregular documents that may have been bought from other movement members as "proof" of their claims.[44] It is common for sovereign citizen "gurus" to earn money by selling their followers standard documents such as template filings, scripts to recite at court appearances, or other "quick-fix" solutions to legal problems.[8] Some "gurus" sell "how-to" manuals explaining the movement's theories and schemes. One such manual is Title 4 Flag Says You're Schwag: The Sovereign Citizen's Handbook, which has been reprinted and updated several times.[70]

Sovereign citizens often use an unusual vocabulary[26] and twist the meaning of legal terms, or even commonplace phrases, for their convenience. This includes avoiding the use of expressions they think would make them enter into a "contract" with the government. For example, when dealing with the police, sovereign citizens will often avoid saying "I understand" and instead say "I comprehend", as they believe that the word "understand" acknowledges that one "stand[s] under the jurisdiction", thus recognizing the police's authority.[92]

As they regard themselves as bound only by their own interpretation of common law, sovereign citizens have been setting up militias of self-appointed "sheriffs",[41] as well as "common law courts", to handle matters regarding movement members. These "courts", which are devoid of legal authority, are frequently used to formalize the "declarations of sovereignty" of movement members, in a process often known as "asseveration".[26]

Sovereign citizens' conflicts with authorities have occasionally resulted in violence.[2][13][41][68]

Traffic law violations

Sovereign citizens consistently violate traffic laws by refusing to register or insure their vehicles or use driver's licenses or valid license plates.[63][13] Some use homemade license plates and bumper stickers, which can serve the unintended purpose of warning police officers that they are dealing with a sovereign citizen. Most sovereign citizens' interactions with law enforcement take place on the road. As a result, the general public is mostly familiar with the movement through online videos of sovereign citizens' confrontations with traffic officers.[63]

Anti-tax and other financial schemes

Many sovereign citizens engage in various forms of tax resistance, causing disputes with government administrations.[68][93] It is estimated that sovereign citizens and other tax protesters have caused about $1 billion in public losses in the U.S. from 1990 to 2013.[84]

Sovereign citizens use a variety of fraudulent schemes, including filing false securities, to avoid paying taxes, get "refunds" from the government, or eliminate their debts and mortgages.[84] The belief that money is worthless since the gold standard was abandoned has led sovereign citizens to create fictitious financial instruments. One of the first to use this method, in the 1980s, was tax protester and songwriter Tupper Saussy, who created check-like instruments he called "Public Money Office Certificates". Saussy issued these "certificates" primarily as a form of protest, but sovereign citizens have been using false "promissory notes", "bills of exchange", "coupons", "bonds", or "sight drafts" to pay taxes, purchase properties, or fight foreclosures. Some "gurus" have scammed adherents of the movement by selling them such counterfeit instruments.[94] Other scams primarily target victims who are not part of the movement.[95][96]

Sovereign citizens may use the ineffective methods the redemption movement advocates for appropriating the sums from one's purported secret Treasury account: such schemes are sometimes called "money for nothing".[6][97] For example, writing "Accepted for Value" or "Taken for Value" on bills or collection letters supposedly causes them to be paid with the straw man's secret fund[26][98] (this scheme is commonly known as "A4V").[4][70][97] Purported methods for claiming the secret fund include filing a UCC-1 financing statement against one's straw man after "separating" from it.[26]

Documents and formalities

Sovereign citizens are known to create their own irregular, pseudolegal documents, including false passports, license plates, or birth certificates.[99] Sovereign citizen documents may include unusual formalities, such as maxims written in Latin, thumbprints, or stamps in certain places, as well as unconventional, sometimes incomprehensible legalese. Stamps are generally accompanied by signatures (with the sovereign citizen's name signed across them), initials or other markings.[8][70][97]

Signatures and thumbprints are likely to be in red ink or blood, since black and blue inks are believed to indicate corporations.[69] As bonds are canceled using red ink in some U.S. states, sovereign citizens may sign in red ink to signify that they are canceling the bond attached to their birth certificate or to their straw man. Others use red ink because it represents the blood of the "flesh-and-blood person". Other methods to dissociate oneself from the straw man include unusual spelling and writing one's name in a different manner or with punctuation, i.e. "John of the family Doe" instead of "John Doe" or "John-Robert: Doe" instead of "John Robert Doe".[26]

Sovereign citizens often add the Latin phrase sui juris (meaning "of one's own right") to their names on legal documents to signify that they are reserving all the rights to which they are entitled as a free person.[26]

Postage stamps supposedly make pseudolegal documents authoritative, but their meaning varies depending on the "guru". One version has it that stamps grant sovereignty to pseudolaw affiliates: their use on documents purportedly makes one a "postmaster" with equal rights and peer status to nation states.[70]

When signing an official document such as a driver's license, mortgage document, or traffic ticket, sovereign citizens often add under threat, duress, and coercion (or a variation thereof, such as the initials TDC) after or under their name to signify that they are not signing the document voluntarily, which purportedly helps them avoid entering into a "contract" with the illegitimate government and falling under its jurisdiction. Some write TDC after their ZIP codes.[98]

People and groups linked to the movement have been using a constructed language created by American theorist David Wynn Miller, who asserted that this unorthodox version of the English language, variously called "Parse-Syntax-Grammar", "Correct-Language",[100] "Truth Language"[101] or "Quantum Grammar",[8][87] guarantees success in legal proceedings where it constitutes the only "correct" form of communication.[70][100][101]

Litigation and court cases

Cases involving sovereign citizens can cause law enforcement officers and court officials severe problems.[10] Sovereign citizens may challenge the laws, rules, or sentences they disagree with by engaging in the practice known as paper terrorism, which involves filing complaints with legal documents that may be bogus or simply misused. Minor issues such as traffic violations or disagreements over pet-licensing fees may provoke numerous court filings. Courts then find themselves burdened by having to process hundreds of pages of irregular, sometimes incomprehensible documents, straining their resources.[2][68][13][3][8]

When involved in court cases, sovereign citizens generally act as their own lawyers, though sometimes a sovereign citizen "leader" may assist them in court. They often use uncommon or downright disconcerting pseudolegal tactics, and typically deny the court's jurisdiction over them.[8][70][97]

In May 2019, Kim Blandino, a felon residing in Nevada, was found guilty of traffic offenses. He threatened the judge who presided over his hearing that he would file complaints against him and demanded a monetary "settlement" from him.[102] Blandino was charged with extortion and impersonation of an officer. He then filed numerous motions to delay the proceedings and tried to disqualify almost every judge in the district. Blandino's motions required multiple reviews and countless hours of hearings.[8] In March 2022, Blandino was convicted in a jury trial. He then appealed his conviction with similar methods. On December 20, 2023, the Court of Appeals of Nevada affirmed the conviction, noting that Blandino's claims were "merely speculative" and that the court did not need to consider his argument as it was not "cogently argued".[103]

False liens and other harassment tactics

Besides paper terrorism, sovereign citizens have used various techniques of intimidation and harassment to achieve their goals.[13] One method of retaliation they use against public officials or other real or perceived enemies is the filing of false liens. Anyone can file a notice of lien against property such as real estate, vehicles, or other assets of another. In most U.S. states, the validity of liens is not investigated or inquired into at the time of filing. Notices of liens (whether legally valid or not) are a cloud on the title of the property and may affect the property owner's credit rating and ability to obtain home equity loans or refinance the property. Clearing up fraudulent notices of liens may be expensive and time-consuming.[10]

Illegitimate sovereign citizen common law courts also put enemies on "trial": on occasion, sovereign citizens have tried public officials in absentia and sentenced them to death for treason.[2]

Another tactic involves false arbitration entities operated by movement members that issue unilaterally, on their clients' behalf, "rulings" ordering the client's creditors or other victims to pay damages.[59][104][105] In 2022, the Anti-Defamation League reported that although this particular tactic seems to have appeared around 2014, its use had intensified since 2019. According to the ADL's report, these sham rulings are designed, besides targeting specific victims, to clog the court system that sovereign citizens consider illegitimate.[104]

Some sovereign citizens have advocated and practiced adverse possession of properties.[3] Notably, Moorish Sovereigns have cited reparations for slavery as a justification for squatting homes and claiming other people's property as theirs, even though they also target the possessions of African Americans.[106]

In the United States, authorities have identified some people involved in First Amendment audits as sovereign citizens.[107]

Legal status of theories

Sovereign citizens' tactics often succeed in delaying legal proceedings and occasionally confuse or exhaust public officials,[2][8][86] but their arguments are never upheld in court.[6] Their claims have been consistently rejected by courts in various countries, including the U.S., Canada,[6][97] Australia,[108] and New Zealand.[109] Mark Pitcavage, a researcher working for the Anti-Defamation League's Center on Extremism, has summed up sovereign citizen ideology as "magical thinking".[110] One state representative from New Hampshire, Richard Marple, repeatedly tried to introduce legislation that would recognize sovereign citizen ideas, without success.[12]

One crucial flaw of pseudolegal theories in general is that the "common law" they cite is based not on historical precedent but instead on an erroneous perception of traditional English law.[6][70]

In 2012, the Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta's Meads v. Meads decision, pertaining to a contentious divorce case in which the husband used freeman on the land arguments, compiled a decade of Canadian jurisprudence and American academic research about pseudolaw. It went much further than the matters of the case by covering the most common pseudolegal arguments and tactics and refuting them in detail.[97][35] Meads v. Meads, written by Associate Chief Justice John D. Rooke, has since been used as case law by courts in Canada and in other Commonwealth countries.[35]

Immunity from laws and taxes

Pseudolegal documents and arguments claiming that one is personally immune from jurisdiction or should not be paying taxes have never been accepted by any court.[70][111] The idea that one can avoid paying taxes in the country one resides in by renouncing or challenging the validity of one's citizenship and claiming to be a "non-resident alien" is legally baseless. The Internal Revenue Service has refuted in detail "frivolous tax arguments" such as this and the idea that filing tax returns and paying Federal Income tax are "voluntary".[112][113]

In 1990, after Andrew Schneider was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for making a threat by mail, he argued that he was a free, sovereign citizen and therefore not subject to the jurisdiction of federal courts. The United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit rejected his argument as having "no conceivable validity in American law".[114] In 2017, former Subway spokesman Jared Fogle similarly tried to overturn his convictions on child sex tourism and child pornography charges by denying the court's jurisdiction over him. The court dismissed Fogle's motions, reminding him that "the Seventh Circuit has rejected theories of individual sovereignty, immunity from prosecution, and their ilk".[115][116]

When he faced tax evasion charges in 2006, actor Wesley Snipes adopted a sovereign citizen line of defense by claiming to be a "non-resident alien" who should not be subject to income tax. He was eventually found guilty of three misdemeanor counts of failing to file federal income tax returns and sentenced to 36 months in prison.[117][118]

The belief that legal obligations are contracts that can be opted out of fails to acknowledge that government and court authority is not a product of one's consent, and that the relationship between the state and an individual is not based on a contract.[119] The Canadian decision Meads v. Meads refuted the theory that laws are contracts, commenting:

A claim that the relationship between an individual and the state is always one of contract is clearly incorrect. Aspects of that relationship may flow from mutual contract (for example a person or corporation may be hired by the government to perform a task such as road maintenance), but the state has the right to engage in unilateral action, subject to the Charter, and the allocation and delegation of government authority.[97]

In a 2013 criminal case, the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington responded to pseudolegal filings by sovereign citizen Kenneth Wayne Leaming with the following comments:

The Court [...] feels some measure of responsibility to inform Defendant that all the fancy legal-sounding things he has read on the internet are make-believe.[111] Defendant can call himself a "public minister" and "private attorney general", he may file "mandatory judicial notices" citing all his favorite websites, he can even address mail to the "Washington Republic". But at the end of the day, while sovereign citizens and Defendant cite things like "Universal Law Ordinances", they are subject to both state and federal laws, just like everyone else.[120][121]

In 2021, Pauline Bauer, a Pennsylvania restaurant owner facing charges for participating in the Capitol riot,[122] used a sovereign citizen line of defense by claiming to be a "self-governed individual"[110] and a "Free Living Soul"[92] and thus immune to prosecution. She was jailed for one day for contempt of court[110][123] and later remanded to jail pending trial for refusing to cooperate with the court or comply with the conditions of her release.[122][124] In January 2023, Bauer was found guilty on all counts of misdemeanor and of the felony of obstructing an official proceeding.[125] In May, she was sentenced to 27 months in prison.[126] Bauer's co-defendant, who had pleaded guilty to a misdemeanor, was sentenced to probation and to a $500 fine.[125]

In 2022, Darrell Brooks, the perpetrator of the Waukesha Christmas parade attack, claimed to be "sovereign"[38] and used other pseudolegal arguments as part of his pro se defense.[127][128][129] Judge Jennifer Dorow ruled that Brooks was not allowed to argue he was sovereign citizen in court, saying the defense was without merit;[130] she said that sovereign citizen legal theories are "nonsense" and that the movement's tactics had no place in the judicial system.[131] Brooks was found guilty on all counts[132] and sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.[133]

"Gurus" Bonnie and David Straight sold to their adherents processes and documents (such as "noncitizen national passports" and illegal license plates) purported to give them "American State National" status and make them immune to U.S. jurisdiction. The Straights' methods were proved ineffective when they were arrested and detained on various charges in April 2023.[61] Bonnie Straight was sentenced to five years' imprisonment: the court rejected her arguments that it did not have jurisdiction over her.[134]

The sovereign citizen concept that U.S. courts are secretly admiralty courts and thus have no jurisdiction over people has been repeatedly dismissed as frivolous.[135][136]

Author Richard Abanes writes that sovereign citizens fail to sufficiently examine the context of the case law they cite, and ignore adverse evidence, such as Federalist No. 15, wherein Alexander Hamilton expressed the view that the Constitution placed everyone personally under federal authority.[78]

Strawman theory and redemption schemes

The core redemption/A4V theory that people possess vast sums of money hidden from them by the government in a secret account, and that this money can be unlocked through specific means, has no basis in reality. Likewise, the strawman theory has been repeatedly dismissed by courts. Both theories are listed by the FBI as common fraud schemes.[137] In 2021, the District Court of Queensland dismissed an application that relied on the strawman theory, commenting that this argument "may properly be described as nonsense or gobbledygook".[138] Redemption methods such as "Accepted for Value" are based on a misinterpretation of the Uniform Commercial Code and have no effect.[26]

Roger Elvick, the originator of the redemption movement, was convicted in 1991 in Hawaii of passing more than $1 million in false sight drafts, and of filing fraudulent IRS forms. He was sentenced to five years in federal prison. Upon his release, Elvick resumed his activities, conceiving the strawman theory at that point. In 2003, he was indicted in Ohio on multiple felony counts. During preliminary hearings, Elvick disrupted proceedings by denying his identity and claiming that the court had no jurisdiction over him or his "strawman". A judge ruled Elvick mentally unfit to stand trial and committed him to a correctional psychiatric facility. After nine months of treatment, Elvick stood trial and pleaded guilty; in April 2005, he was sentenced to four years in prison.[139]

Heather Ann Tucci-Jarraf, a licensed lawyer who had been at one point a state prosecutor, eventually joined the sovereign citizen movement: she built an online following as a "guru" and advocated the use of redemption methods to reclaim one's alleged secret fund from the banking system and the Federal Reserve. One of her followers, Randall Beane, used Internet fraud to embezzle two million dollars, which he believed were part of his secret account; Tucci-Jarraf was aware of Beane's scheme and advised him throughout. Beane and Tucci-Jarraf were arrested and charged with federal crimes. Both were found guilty of conspiracy to launder money in 2018, with Beane also being convicted of wire and bank fraud. The court ruled that Tucci-Jarraf, having used her legal training to assist Beane, was an aggravating circumstance.[140][141][142][143] Beane was sentenced to 155 months in prison, and Tucci-Jarraf to 57 months.[87]

Creating and selling fictitious financial instruments is likewise a scam. People who purchased sovereign citizen instruments purported to help them pay off their debts or avoid foreclosures have worsened their situation by doing so.[94] Winston Shrout, an influential sovereign citizen "guru" based in Oregon, who advocated tax resistance and redemption/A4V schemes, issued hundreds of fake "bills of exchange" for himself and others, and eventually mailed to a bank one quadrillion dollars in counterfeit securities supposedly to be honored by the Treasury.[93][144] Shrout was charged in 2016 with 13 counts of using fictitious financial instruments.[33] In 2017, he was found guilty of several counts of tax evasion and producing fraudulent documents. The next year, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison. Several of Shrout's followers who had tested his ideas, including his daughter, were also sentenced.[145][93][144]

Traffic

Sovereign citizens' argument that they do not need driver's licenses, license plates, and vehicle insurances has never been upheld in court.[63] One common response to this claim from U.S. law enforcement is that, while anyone is free to "travel" by foot, by bike or even by horse, operating a motor vehicle is a complex activity that requires training and licensure.[52]

Sovereign Citizens falsely claim that the United States Supreme Court has upheld the right to travel as allowing operation of a motor vehicle without a driver's license.[146] On the contrary, several rulings state that drivers' licenses and traffic regulations are necessary for public safety.[147][148][149]

Sovereign citizen legal entities

Sovereign citizens' "common law courts" and other "legal" entities lack any legitimacy. Some may be simply ignored by authorities: in 2015, sovereign citizen "guru" Anna Maria Riezinger aka Anna von Reitz, the self-proclaimed "judge" of a common law court in Alaska,[31] published a letter calling for federal agents to arrest President Barack Obama, the entire Congress and the Secretary of the Treasury,[57] causing a minor Internet rumor. Snopes debunked her claim by establishing that von Reitz was not a real judge and that her "orders" therefore had no force.[150]

However, depending on the nature and severity of their actions, sovereign citizen "courts" may be disbanded and their leaders prosecuted.[51]

In 2016, after David Wynn Miller's "Federal Postal court" issued a $11.5 million judgement against a mortgage service company, a federal judge investigated that entity and ruled that it was "a sham and no more than a product of fertile imagination".[151] Two years later, Leighton Ward, who worked as "clerk" of this false court[151] and had used this capacity as part of a mortgage elimination scheme based on the use of Miller's language,[152] was sentenced in Arizona to 23+1⁄2 years in prison for fraudulent schemes and artifices.[153][154][155]

During the 2010s, computer repair shop owner Bruce Doucette, who styled himself as "Superior Court Judge of the Continental uNited States of America" and led a group called "The People's Grand Jury in Colorado", traveled the country to help other sovereign citizens fight local governments and set up their own "common law courts".[156][157][158][159] He and his followers attempted to intimidate public officials so they would dismiss criminal cases against other sovereign citizens.[160] When these efforts failed, Doucette's group retaliated by engaging in paper terrorism against them[157] with false subpoenas and liens,[156][161] and threatening them with "arrest" by their self-appointed "Marshals".[160] Doucette and a number of his associates were arrested and charged with multiple felony counts.[156][159] In May 2018, Colorado's 18th Judicial District ruled that Doucette's network of "common law courts" was a racketeering enterprise equivalent to organized crime and also found Doucette guilty of retaliation against several judges and attempting to influence a public servant. He was sentenced to 38 years in prison.[160] Two of his co-defendants were sentenced to 36 and 22 years, respectively.[157] Colorado prosecutors commented that through this verdict, they wished to send a message nationally to sovereign citizens and remind them that threats against local government officials would not be tolerated.[159]

Randal Rosado, a Florida resident, created a series of false legal entities, including an "International Court of Commerce", and used them to file fictitious arrest warrants, court orders and liens against public officials and lawyers, most of whom had been involved in foreclosures. In September 2019, Rosado was sentenced to 40 years in prison on numerous counts of unlawful retaliation against public officials and of simulating the legal process.[162][163][164]

In August 2021, Sitcomm Arbitration Association, the largest sovereign citizen "arbitration" entity,[165] was held liable for a $1,384,371.24 fine in a default judgment for violation of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act.[166]

Other arguments and schemes

The claim that the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1871 turned the United States into a business corporation is based on a misunderstanding of the term municipal corporation used in the Act (which referred to the District of Columbia and not to the entire country)[167][168] and on a misinterpretation of a provision in Title 28 of the United States Code, which includes a definition of the United States as a "federal corporation" (meaning a group authorized to legally act as a single entity and not a business corporation).[64]

The theories that "silence means consent" and that an unrebutted affidavit stands as truth are based on misinterpretations of the legal maxim "He who does not deny, admits".[70]

The idea that "there is no crime if there is no injured party" is based on a misinterpretation of tort law[70] and fails to recognize the existence of different levels of legal violations.[52]

Filing fraudulent notices of liens or documents is a crime in the United States.[10] Other forms of paper terrorism may be similarly punished by law: Brett Andrew Nelson, a sovereign citizen from Colorado, spent years filing "claims of damages" against judges and other public officials, as well as private citizens whom he felt had wronged him. His conflict with the judiciary started in 2017 over a child custody dispute. He later issued numerous false "judgements", demanding thousand of dollars from officials who had fined him for issues such as traffic violations and dog bites, and similarly harassed the mother of his child and people from his neighborhood. In April 2024, Nelson was sentenced to 12 years in prison.[169][170]

American courts have routinely dismissed documents written in David Wynn Miller's "Parse-Syntax-Grammar"/"Quantum Grammar" language, calling them unintelligible.[100][171][172][173] Canadian judge John D. Rooke commented, in his Meads v. Meads decision, that Miller's "bizarre form of 'legal grammar'" is "not merely incomprehensible in Canada, but equally so in any other jurisdiction".[97]

The Universal Postal Union, which is often invoked as a supranational authority in sovereign citizen schemes,[70] has officially denied that it has "the authority to confer official recognition" upon sovereign citizens, "or to grant some kind of formal status to such individuals", also specifying that "the use of postage stamps on legal documents does not create an opportunity or obligation for the UPU to become involved in those matters".[174]

Groups outside the United States

There is some cross-over between the two groups calling themselves freemen on the land and sovereign citizens, as well as various others sharing similar beliefs, which may be loosely defined as "see[ing] the state as a corporation with no authority over free citizens".[20]

English-speaking countries

With the advent of the Internet and continuing during the 21st century, people throughout the Anglosphere who share the core beliefs of these movements have been able to connect and share their ideas. While arguments specific to the history and laws of the United States are not used (except inadvertently, by litigants who use poorly adapted U.S. material),[97] many concepts have been incorporated or adopted by individuals and groups in English-speaking Commonwealth countries.[20][175] In Canada, which has its own tradition of tax protesters,[176] fiscal misconceptions of American origin were gradually introduced during the 1980s and 1990s.[4]

Around 1999–2000, sovereign citizen and redemption concepts were introduced into Canada by Eldon Warman, who adapted them to a Commonwealth context. These ideas were further adapted in Canada by the freeman on the land movement, which espouses an ideology broadly similar to that of the sovereign citizen movement, but is aimed at a less conservative audience. Canadian-style freeman of the land ideas were later imported into other Commonwealth countries, but American-style sovereign citizen ideology has also reached these regions of the world.[4][177][178]

As of the 2010s, there are people identifying as sovereign citizens in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and South Africa.[70][20][179] Sovereign citizens from the U.S. have gone on speaking tours to New Zealand and Australia, appealing to struggling farmers, and there are Internet presences in both countries.[20]

Canada

Whilst the more Canada-specific freeman on the land movement has declined since the early 2010s,[4] the Canadian sovereign citizen movement has gained traction during the same period.[180] Canada had an estimated 30,000 sovereign citizens in 2015, many associating with the freeman on the land movement as well.[181] There can be confusion between the two populations.[35][182]

Legal scholar Donald J. Netolitzky makes a distinction between the Canadian sovereign citizen and freeman on the land movements, in that freemen on the land, while ideologically heterogenous, tend to be politically more left leaning than sovereign citizens.[35]

The 2012 Meads v. Meads ruling examined almost 150 cases involving pseudolaw and sovereign citizen or freeman of the land tactics, grouping them and characterizing them as "Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Arguments".[97][70]

In 2024 lawyer Naomi Arbabi resigned her license after being suspended by the Law Society of British Columbia for filing a lawsuit dismissed as frivolous making use of pseudo-legal arguments like those of the sovereign citizen movement.[183]

Australia

Australia, which has its own tradition of pseudolaw, imported sovereign citizen ideas in the 1990s, even before the movement's 2000s resurgence. It later imported the more Commonwealth-specific freeman on the land movement.[4] There is some cross-over between Australian freemen on the land,[184] local sovereign citizens groups, and some others.[20][184] The core concept has been tested by several court cases, none successful for the "freemen".[185] In 2011, climate denier and political activist Malcolm Roberts (later elected senator for Pauline Hanson's One Nation party), wrote a letter to then Prime Minister Julia Gillard filled with characteristic sovereign citizen ideas and vocabulary, although he denied that he was a "sovereign citizen".[186][187]

From the 2010s, there has been a growing number of freemen targeting Indigenous Australians, with groups using names like Tribal Sovereign Parliament of Gondwana Land, the Original Sovereign Tribal Federation (OSTF) and the Original Sovereign Confederation. OSTF Founder Mark McMurtrie, an Aboriginal man, has produced YouTube videos speaking about "common law", which incorporate freemen beliefs. Appealing to other Aboriginal people by partly identifying with the land rights movement, McMurtrie played on their feelings of alienation and lack of trust in the systems which had not served Indigenous people well.[188][189]

In 2015, the New South Wales Police Force identified "sovereign citizens" as a potential terrorist threat, estimating that there were about 300 sovereign citizens in the state at the time.[190] Freemen/sovereign citizen ideas have been promoted on the Internet by various Australian groups such as "United Rights Australia" (U R Australia).[20][191]

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the spread of the movement in Australia; numerous incidents with law enforcement have since been reported, some of them violent such as the 2022 Wieambilla shootings.[192]

New Zealand

New Zealand, which has imported foreign pseudolaw including Canadian freeman of the land ideology, has developed its own sovereign citizen movement.[4] In 2024, police identified 1,400 New Zealanders as acting under the influence of sovereign citizen ideology.[193] Many litigants using pseudolegal concepts in New Zealand are Maori.[4]

United Kingdom

Sovereign citizen ideology reached the United Kingdom around 2010.[34] British sovereign citizens have helped spread COVID vaccine misinformation as well as various conspiracy theories – including 9/11 theories and one about the Queen having been replaced by a satanic cabal – and tried to set up their own cryptocurrency.[44]

The Common Law Court website, one of the main UK sovereign citizen resources, has for a time supported an impostor who claimed to be the rightful heir to the British throne.[44] The group known as The Sovereign Project claims to have 20,000 members as at 2024.[195]

Austria and Germany

The Reichsbürger (lit. 'imperial citizen') movement in Germany originated around 1985 and had approximately 19,000 members in 2019, more concentrated in the south and east. The originator claimed to have been appointed head of the post-World War I Reich, but other leaders claim imperial authority. The movement consists of different, usually small groups. Some groups have issued passports and identification cards.[196][197] The Reichsbürger movement claims that modern day Germany is not a sovereign state but a corporation created by Allied nations after World War II. They also expressed their hope that Donald Trump would lead an army to restore the empire.[198] According to the German domestic intelligence service, only a small number of groups in the Reich citizen movement fall into the far-right spectrum. Rather, the common denominator is the rejection of the Federal Republic as a legal entity.[199] The Reichsbürger movement has used language and techniques from the One People's Public Trust, an American sovereign citizen group operated by "guru" Heather Ann Tucci-Jarraf.[87] On December 7, 2022, 25 people connected to the Reichsbürger movement were arrested in a nationwide raid by German police forces, for their involvement in a suspected terrorist plot against the German government and institutions.[200]

In Austria, the group Staatenbund Österreich ('Austrian Commonwealth'), in addition to issuing its own passports and licence plates, had a written constitution.[201] The group, established in November 2015, also used language from the One People's Public Trust.[202] In 2019, its leader was sentenced to 14 years in jail after trying to order the army to overthrow the government and requesting foreign assistance from Vladimir Putin; other members received lesser sentences.[203]

Italy

As of the 2010s, incidents involving sovereign citizens have been reported in Italy, with various people purporting to opt out of Italian citizenship through nonlegal procedures and make themselves immune from Italian law. Members of one group attempt to do so by declaring themselves citizens of the "Sovereign Kingdom of Gaia" (Regno Sovrano di Gaia) while others refer to themselves as the "People of Mother Earth" (Popolo della Terra Madre).[204] Another group called "We is, I am" (Noi è, Io sono) was reported in 2023. This movement is connected with American "guru" Heather Ann Tucci-Jarraf[205] and, according to Italian media, had about 10 000 followers in 2023.[206][207]

Russia

A Russian movement of conspiracy theorists, known among other names as the Union of Slavic Forces of Russia (Союз славянских сил Руси, Soyuz slavyanskikh sil Rusi), or more informally as "Soviet Citizens", holds that the Soviet Union still exists de jure and that the current Russian government and legislation are thus illegitimate. One of its beliefs is that the government of the Russian Federation is an offshore company through which the United States illegally controls the country.[208][209][210]

France and Belgium

In France, pseudolegal arguments claiming that enacted laws were invalid became gradually popular during the 2010s among conspiracy theorists. They gained more traction during the yellow vests protests, with claims that the Constitution of France was null and void.[211]

A New Age-oriented French group of conspiracy theorists called "One Nation" became known to the public in 2021 for their involvement in the kidnapping of a child. Later that year, they attempted to purchase a property in Lot, purportedly to create a "center for the arts" and a "research laboratory". The One Nation movement holds beliefs similar to those of American sovereign citizens and denies the legitimacy of the French State. They also share beliefs with QAnon. The group translates the name "sovereign citizens" in French as êtres souverains (sovereign beings) or êtres éveillés (awakened beings).[212][213][214][215]

In 2021, people affiliated with One Nation were reported to be active in Belgium.[216] In February 2022, the group's French spokeswoman was sentenced to six months in prison for multiple traffic violations.[217] She was arrested and incarcerated in September of the same year.[218]

In 2024, sovereign citizen ideology became more familiar to the French general public due to the viral video of an incident between a couple of conspiracy theorists and traffic police.[219][211] It was also reported that the movement was gaining more followers in Belgium.[220]

Czech Republic

The movement was first covered by Czech media in 2022, when the government noticed an increasing number of people submitting a "sworn declaration of life" and demanding to terminate a contract with the "Czech Republic corporation".[221][222] It gained further traction in the middle of 2023, when sovereign citizen movement followers tried to interrupt multiple court proceedings involving disseminators of COVID-19 and Russo-Ukrainian War disinformation, demanding that the judges "identify" themselves.[223][224] The movement was also connected to a case of a family with two unregistered children living in a yurt near Náchod.[225]

Czech members of the movement maintain that they remain de jure citizens of Czechoslovakia, based on a belief that the dissolution of Czechoslovakia was illegal.[222] There are multiple active groups based on the sovereign citizen ideology, the most prominent one being the "Community of Legitimate Creditors of the Czech Republic" (Czech: Společenství legitimních věřitelů České republiky).[226]

See also

Violent incidents

- 1995 Oklahoma City bombing

- 2003 standoff in Abbeville, South Carolina

- 2009 assassination of George Tiller

- 2010 West Memphis police shootings

- 2014 Bundy standoff

- 2016 occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge

- 2016 shooting of Baton Rouge police officers

- 2016 shooting of Korryn Gaines

- 2018 Nashville Waffle House shooting

- 2021 Wakefield, Massachusetts standoff

- 2021 Waukesha Christmas parade attack

- 2022 Wieambilla police shootings

Groups

- American militia movement

- Christian Patriot movement

- Citizens for Constitutional Freedom

- Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association

- Embassy of Heaven

- Family Farm Preservation

- Guardians of the Free Republics

- Kingdom Filipina Hacienda

- Montana Freemen

- Moorish Sovereign Citizens

- Patriot movement

- Posse Comitatus movement

- Sitcomm Arbitration Association

- Swissindo

- Washitaw Nation

Individuals

Concepts

- Anarcho-capitalism

- Anarchism and nationalism

- Anomie

- Anti-Federalism

- Antinomianism

- Consent of the governed

- Debt evasion

- Declarationism

- Individualist anarchism

- National-anarchism

- Paleoconservatism

- Paleolibertarianism

- Radical right (United States)

- Right-libertarianism

- Self-ownership

- Social contract

- Sovereignty

- Statelessness

- Tax resistance in the United States

- White supremacy

Other

References

- ^ a b c Kaz Ross (July 28, 2020), "Why do 'living people' believe they have immunity from the law?", University of Tasmania, retrieved January 20, 2022

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Laird, Lorelei (May 1, 2014), "'Sovereign citizens' plaster courts with bogus legal filings – and some turn to violence", ABA Journal, archived from the original on November 2, 2014, retrieved June 22, 2020

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Sovereign Citizens Movement, Southern Poverty Law Center, retrieved January 6, 2022

- ^ a b c d e f g h Netolitzky, Donald (May 3, 2018). A Pathogen Astride the Minds of Men: The Epidemiological History of Pseudolaw (Report). SSRN 3177472.

- ^ a b Domestic Terrorism. The Sovereign Citizen Movement, Federal Bureau of Investigation, April 13, 2010, retrieved February 6, 2022

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Netolitzky, Donald (May 3, 2018). A Rebellion of Furious Paper: Pseudolaw As a Revolutionary Legal System (Report). SSRN 3177484.

- ^ "Message for Students: What Is the Sovereign Citizen Movement?" Archived January 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Militia Watchdog Archives. Anti-Defamation League.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lee, Calvin (March 2, 2022). "Sovereign citizens: sitting on the docket all day, wasting time". Minnesota Law Review. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carey, Kevin (July 2008). "Too Weird for The Wire". Washington Monthly. May/June/July 2008. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Goode, Erica (August 23, 2013). "In Paper War, Flood of Liens Is the Weapon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Moorish Sovereign Citizens, Southern Poverty Law Center, archived from the original on July 11, 2019, retrieved July 11, 2019

- ^ a b c Weill, Kelly (January 4, 2018), "Republican Lawmaker: Recognize Sovereign Citizens or Pay $10,000 Fine", Daily Beast, retrieved August 4, 2020

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p The Sovereign Citizen Movement in the United States, Anti-Defamation League, December 21, 2023, retrieved June 12, 2024

- ^ Allison Sherry (May 22, 2018), 'Sovereign Citizen' Bruce Doucette Sentenced To 38 years, Colorado Public Radio, retrieved February 3, 2022

- ^ a b Johnson, Kevin (March 30, 2012). "Anti-government 'Sovereign Movement' on the rise in U.S." USA Today. Archived from the original on December 16, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "Sovereign Citizens A Growing Domestic Threat to Law Enforcement". Domestic Terrorism. Federal Bureau of Investigation. September 1, 2011. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ^ Rivinius, Jessica (July 30, 2014). "Sovereign citizen movement perceived as top terrorist threat". National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. Archived from the original on August 6, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ David Carter; Steve Chermak; Jeremy Carter; Jack Drew. "Understanding Law Enforcement Intelligence Processes: Report to the Office of University Programs, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security, July 2014, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (College Park, Maryland)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ Thomas, James; McGregor, Jeanavive (November 30, 2015). "Sovereign citizens: Terrorism assessment warns of rising threat from anti-government extremists". ABC News. Australia. Archived from the original on November 30, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kent, Stephen A. (2015). "Freemen, Sovereign Citizens, and the Challenge to Public Order in British Heritage Countries" (PDF). International Journal of Cultic Studies. 6: 1–15. OCLC 5807743608. EBSCOhost 101149893.

- ^ Balleck, Barry (2014). Allegiance to Liberty: The Changing Face of Patriots, Militias, and Political Violence in America. Praeger. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-1-4408-3095-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Hodge, Edwin (November 26, 2019). "The Sovereign Ascendant: Financial Collapse, Status Anxiety, and the Rebirth of the Sovereign Citizen Movement". Frontiers in Sociology. 4: 76. doi:10.3389/fsoc.2019.00076. PMC 8022456. PMID 33869398.

- ^ Miller, Joshua Rhett (January 5, 2014), "Sovereign citizen movement rejects gov't with tactics ranging from mischief to violence", Fox News, retrieved June 22, 2020

- ^ Schneider, Keith (December 7, 1987), "Economics, Hate and the Farm Crisis", The New York Times, retrieved December 18, 2022

- ^ Atkins, Stephen E. (September 13, 2011). Encyclopedia of Right-Wing Extremism In Modern American History. ABC-CLIO. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-59884-351-4. Retrieved August 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j The Sovereigns: A Dictionary of the Peculiar, Southern Poverty Law Center, August 1, 2010, retrieved January 20, 2022

- ^ Montana Freemen Trial May Mark End of an Era, Southern Poverty Law Center, June 15, 1998, retrieved March 30, 2024

- ^ Tom Kenworthy and Serge F. Kovaleski "`Freemen' Finally Taxed the Patience of Federal Government". Washington Post. March 31, 1996.

- ^ Goldberg, Carey (June 14, 1996). "Last of Freemen Surrender to F.B.I. at Montana Site". New York Times. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ^ "Supermax inmate, 72, found dead Canon City (CO) Daily Record – September 21, 2011". Canoncitydailyrecord.com. September 21, 2011. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Green, Sarah Jean (June 23, 2022). "Fall City extremist's eviction throws spotlight on sovereign citizen movement". The Seattle Times. Retrieved November 17, 2022.