Politics of the Southern United States

The politics of the Southern United States generally refers to the political landscape of the Southern United States. The institution of slavery had a profound impact on the politics of the Southern United States, causing the American Civil War and continued subjugation of African-Americans from the Reconstruction era to the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Scholars have linked slavery to contemporary political attitudes, including racial resentment.[2] From the Reconstruction era to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, pockets of the Southern United States were characterized as being "authoritarian enclaves".[3][4][5][6]

The region was once referred to as the Solid South, due to its large consistent support for Democrats in all elective offices from 1877 to 1964. As a result, its Congressmen gained seniority across many terms, thus enabling them to control many congressional committees. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, Southern states became more reliably Republican in presidential politics, while Northeastern states became more reliably Democratic.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] Studies show that some Southern whites during the 1960s shifted to the Republican Party, in part due to racial conservatism.[13][15][16] Majority support for the Democratic Party amongst Southern whites first fell away at the presidential level, and several decades later at the state and local levels.[17] Both parties are competitive in a handful of Southern states, known as swing states.

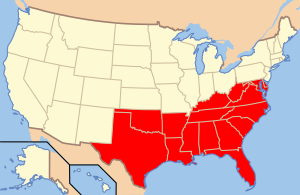

Southern states

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the following states are considered part of the South:

- Alabama

- Arkansas

- Delaware

- Florida

- Georgia

- Kentucky

- Louisiana

- Maryland

- Mississippi

- North Carolina

- Oklahoma

- South Carolina

- Tennessee

- Texas

- Virginia

- West Virginia

Other definitions vary. For example, Missouri is often considered a border or Midwestern state, although many Ozark Missourians claim Missouri as a Southern state.[18]

Post-Civil War through 19th century

[edit]At the end of the Civil War, the South entered the Reconstruction era (1865–1877). The Reconstruction Acts of 1867 and 1868 placed most of the Confederate states under military rule (except Tennessee), which required Union Army governors to approve appointed officials and candidates for election. They enfranchised African American citizens and required voters to recite an oath of allegiance to the U.S. Constitution, effectively discouraging still-rebellious individuals from voting, and led to Republican control of many state governments.[19] This was interpreted as anarchy and upheaval by many residents.[20] However, Democrats would regain power in most Southern states by the late 1870s. Later, this period came to be referred to as Redemption. From 1890–1908 states of the former Confederacy passed statutes and amendments to their state constitutions, that effectively disenfranchised African Americans from voting, as well as some poor whites. They did this through devices such as poll taxes and literacy tests.[21]

In the 1890s the South split bitterly, with poor cotton farmers moving to the Populist movement. In coalition with the remaining Republicans, the Populists briefly controlled Alabama and North Carolina. The local elites, townspeople, and landowners fought back, regaining control of the Democratic party by 1898.

20th century

[edit]During the 20th century, civil rights of African Americans became a central issue. Before 1964, African American citizens in the South and elsewhere in the United States were treated as second class citizens with minimal political rights.

1948: Dixiecrat revolt

[edit]Few Southern Democrats rejected the 1948 Democratic political platform over President Harry's Truman's civil rights platform.[22] They met at Birmingham, Alabama, and formed a political party named the "States' Rights" Democratic Party, more commonly known as the "Dixiecrats." Its main goal was to continue the policy of racial segregation and the Jim Crow laws that sustained it. South Carolina Governor Strom Thurmond, who had led the walkout, became the party's presidential nominee. Mississippi Governor Fielding L. Wright received the vice-presidential nomination. Thurmond had a moderate position in South Carolina politics, but with his allegiance with the Dixiecrats, he became the symbol of die-hard segregation.[23] The Dixiecrats had no chance of winning the election since they failed to qualify for the ballots of enough states. Their strategy was to win enough Southern states to deny Truman an electoral college victory and force the election into the House of Representatives, where they could then extract concessions from either Truman or his opponent Thomas Dewey on racial issues in exchange for their support. Even if Dewey won the election outright, the Dixiecrats hoped that their defection would show that the Democratic Party needed Southern support to win national elections, and that this fact would weaken the Civil Rights Movement among Northern and Western Democrats. However, the Dixiecrats were weakened when most Southern Democratic leaders (such as Governor Herman Talmadge of Georgia and "Boss" E. H. Crump of Tennessee) refused to support the party.[24] In the November election, Thurmond carried the Deep South states of Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina.[25] Outside of these four states however, it was only listed as a third-party ticket. Thurmond would receive well over a million popular votes and 39 electoral votes.[25]

Civil Rights Movement

[edit]Between 1955 and 1968, a movement towards desegregation began to take place in the American South. Martin Luther King Jr., a Baptist minister, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were highly influential in carrying out a strategy of non-violent protests and demonstrations. African American churches were prominent in organizing their congregations for leadership and protest. Protesters rallied against racial laws, at events such as the Montgomery bus boycott, the Selma to Montgomery marches, the Birmingham campaign, the Greensboro sit-in of 1960, and the March on Washington in 1963.[26]

Legal changes came in the mid-1960s when President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 through Congress. It ended legal segregation. He also pushed through the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which set strict rules for protecting the right of African Americans to vote. This law has since been used to protect equal rights for all minorities as well as women.[27]

Republican gains

[edit]For nearly a century after Reconstruction (1865–1877), the majority of the white South identified with the Democratic Party. Republicans during this time would only control parts of the mountains districts in southern Appalachia and competed for statewide office in the former border states. Before 1948, Southern Democrats believed that their stance on states' rights and appreciation of traditional southern values, was the defender of the southern way of life. Southern Democrats warned against designs on the part of northern liberals, Republicans (including Southern Republicans), and civil rights activists, whom they denounced as "outside agitators".[citation needed]

The adoption of the first civil rights plank by the 1948 convention and President Truman's Executive Order 9981, which provided for equal treatment and opportunity for African-American military service members, divided the Democratic party's northern and southern wings.[28] In 1952, the Democratic Party named John Sparkman, a moderate Senator from Alabama, as their vice presidential candidate with the hope of building party loyalty in the South.[29][30] By the late 1950s, the national Democratic Party again began to embrace the Civil Rights Movement, and the old argument that Southern whites had to vote for Democrats to protect segregation grew weaker. Modernization had brought factories, national businesses and a more diverse culture to cities such as Atlanta, Dallas, Charlotte and Houston. This attracted millions of U.S. migrants from outside the region, including many African Americans to Southern cities. They gave priority to modernization and economic growth, over preservation of the old economic ways.[31]

After the Civil Rights act of 1964 and The Voting Rights Act of 1965 were passed in Congress, only a small element resisted, led by Democratic governors Lester Maddox of Georgia, and especially George Wallace of Alabama. These populist governors appealed to a less-educated, working-class electorate, that favored the Democratic Party, but also supported segregation.[32] After the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case that outlawed segregation in schools in 1954, integration caused enormous controversy in the white South. For this reason, compliance was very slow and was the subject of violent resistance in some areas.[33]

The Democratic Party no longer acted as the champion of segregation. Newly enfranchised African American voters began supporting Democratic candidates at the 80-90-percent levels, producing Democratic leaders such as Julian Bond and John Lewis of Georgia, and Barbara Jordan of Texas.[34]

Many white southerners switched to the Republican Party during the 1960s, for a variety of reasons. The majority of white southerners shared conservative positions on taxes, moral values, and national security. The Democratic Party had increasingly liberal positions rejected by these voters.[35] In addition, the younger generations, who were politically conservative but wealthier and less attached to the Democratic Party, replaced the older generations who remained loyal to the party.[35] The shift to the Republican Party took place slowly and gradually over almost a century.[35]

Late 20th century into 21st century

[edit]By the 1990s Republicans were starting to win elections at the statewide and local level throughout the South, even though Democrats retained majorities in several state legislatures through the 2000s and 2010s.[35][36] By 2014, the region was heavily Republican at the local, state and national level.[36][37] A key element in the change was the transformation of evangelical white Protestants in the south from largely nonpolitical to heavily Republican. Pew pollsters reported, "In the late 1980s, white evangelicals in the South were still mostly wedded to the Democratic Party while evangelicals outside the South were more aligned with the GOP. But over the course of the next decade or so, the GOP made gains among white Southerners generally and evangelicals in particular, virtually eliminating this regional disparity."[38] Exit polls in the 2004 presidential election showed that Republican George W. Bush led Democrat John Kerry by 70–30% among Southern whites, who comprised 71% of the voters there. By contrast, Kerry had a 90–9 lead among the 18% of African American Southern voters. One-third of the Southern voters said they were white evangelicals; they voted for Bush by 80–20.[39]

2016–present

[edit]After the 2016 elections, nearly every state legislature in the South was GOP-controlled.[40] Republican nominee for President Donald Trump notably won Elliott County, KY, becoming the first Republican presidential nominee to ever win that county.[41] Following the 2019 elections, Democrats won control of Virginia's House of Delegates and State Senate, thus giving them trifecta over the state government for the first time since the 1990s.[42] However, in 2021, Virginians would elect Glenn Youngkin as Governor and Republicans would retake control of the House of Delegates with a 52–48 majority.[43] During the early 2020s, Georgia began to see itself become electorally competitive for Republicans again as Joe Biden won the state in 2020 election. Furthermore, Georgia would elect Democrats Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock as their Senators in concurrent regularly scheduled and special elections, respectively.[44] Warnock would be elected to a full term in 2022 even as Republicans swept all statewide races and retained control of the state legislature.[45]

Connections between education and politics

[edit]Research studies in American political affiliations demonstrate that an "uneducated"(lack of post-secondary school) white populace tends to vote Republican.[46] Looking at the racial composition through the 2022 census[47] demonstrates that the most prevalent race in the south are whites. Using these pieces of information, the tendency for the south to vote Republican could be further be explained as a lack of education in this region of the United States, as there are several majority-white states outside of the Deep South that tend to vote Democratic, but also many uneducated Southern blacks who vote Democrat as well, most likely due to the historical lack of state funding and educational focus in predominantly black schools and counties. (Red states and blue states).

Recent trends

[edit]LGBTQ rights

[edit]In September 2004, Louisiana became the first state to adopt a constitutional ban on same-sex marriage in the South. This was followed by Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Oklahoma in November 2004; Texas in 2005; Alabama, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia in 2006; Florida in 2008; and finally North Carolina in 2012. North Carolina became the 30th state to adopt a state constitutional ban of same-sex marriage.[48] This ended with Obergefell v. Hodges Supreme Court case, which ruled in favor of same-sex marriage nationwide on June 26, 2015.[49] Virginia removed its laws banning same-sex marriage in 2020, but the constitutional amendment banning it is still in place, although not currently enforceable also due to the 2022 Respect for Marriage Act.[50] Republican-majority legislatures in Florida, Tennessee and Texas pushed for increased restrictions on transgender rights and gender-nonconforming expression in the 2020s.

Politics

[edit]While the general trend in the South has shown an increasing dominance of the Republican party since the 1960s, Southern politics in the 21st century are still contentious and competitive.[51] States such as Georgia, Virginia and North Carolina are swing states. Georgia has a Republican governor and 2 Democratic U.S. Senators, Virginia has a Republican governor and 2 Democratic U.S. Senators, and North Carolina has a Democratic Governor and 2 Republican U.S. Senators. Most Southern state legislatures, however, have been governed with Republican supermajorities in both houses at least once since 2000.

All the former Confederate Southern states supported Donald Trump in the 2016 Republican presidential primary except Texas (won by native son Ted Cruz). Trump won every former Confederate State except Virginia.[52]

Most Southern states, since the earlier 20th century, adopted absolute majority requirements in Democratic "white primary" elections for state and local offices, largely to undermine challengers from among both moderates as well as those further to the right, such as members of the Ku Klux Klan. Some states, like Georgia and Mississippi, also adopted tighter thresholds, with Georgia adopting a County unit system for their Democratic primary and Mississippi adopting a requirement that general election candidates win with a majority of state house districts. Several court cases throughout the 20th and even the 21st centuries have challenged these laws. There have also been several changes to the laws, from Louisiana's adoption of the Nonpartisan blanket primary (in the form of the Louisiana primary) to Florida's abolition of the 50% requirement in primary and general elections. However, Georgia (from 1964 to 1994 and since 2005) and Mississippi (since 2020) remain the two states which require absolute majorities in both primaries and general elections.[53]

| Politics in the Southern United States, 2001–present | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| State | Elected office | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

| Alabama | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 R | D, R | 2 R | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | D | R | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | |||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | R supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Arkansas | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | D, R | 2 D | D, R | 2 R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | D majority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | R | D | R | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | |||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Delaware | President | Al Gore (D) | John Kerry (D) | Barack Obama (D) | Hillary Clinton (D) | Joe Biden (D) | ||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 D | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | D majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | D | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | R majority | D majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Florida | President | George W. Bush (R) | Barack Obama (D) | Donald Trump (R) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 D | D, R | 2R | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | R | I | R | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | R majority | R supermajority | R majority | R supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | R majority | R supermajority | R majority | R supermajority | R majority | R supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||

| Georgia | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | Joe Biden (D) | ||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | D, R | 2 R | 2 D | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | D | R | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kentucky | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 R | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | D | R | D | R | D | |||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | R majority | R supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Louisiana | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 D | D, R | 2R | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | R | D | R | D | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | |||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maryland | President | Al Gore (D) | John Kerry (D) | Barack Obama (D) | Hillary Clinton (D) | Joe Biden (D) | ||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 D | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | 4 D, 4 R | D majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | D | R | D | R | D | |||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | D supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Delegates | D supermajority | D majority | D supermajority | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Mississippi | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 R | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | D majority | 2 D, 2 R | D majority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | D | R | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | R majority | D majority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| North Carolina | President | George W. Bush (R) | Barack Obama (D) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | D, R | 2 R | D, R | 2 R | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | D majority | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | D | R | D | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | 60 D, 60 R | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||

| Oklahoma | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 R | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | R | D | R | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | 24 D, 24 R | R majority | R supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | |||||||||||||||||||||

| South Carolina | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | D, R | 2 R | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | D | R | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | R majority | R supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Tennessee | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 R | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | D majority | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | R | D | R | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D majority | 16 R, 16 D, 1 I | R majority | R supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | 49 R, 49 D, 1 CCR | R majority | R supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Texas | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 R | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | D majority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | R | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Virginia | President | George W. Bush (R) | Barack Obama (D) | Hillary Clinton (D) | Joe Biden (D) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 R | D, R | 2 D | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | R majority | D majority | R majority | D majority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | R | D | R | D | R | |||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | R majority | D majority | R majority | D majority | R majority | D majority | ||||||||||||||||||

| House of Delegates | R majority | R supermajority | R majority | D majority | R majority | |||||||||||||||||||

| West Virginia | President | George W. Bush (R) | John McCain (R) | Mitt Romney (R) | Donald Trump (R) | |||||||||||||||||||

| U.S. senators | 2 D | D, R | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Congressional districts | D majority | R majority | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Governor | D | R | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senate | D supermajority | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | ||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | D supermajority | D supermajority | D majority | R majority | R supermajority | |||||||||||||||||||

| Political views and affiliations | % living in the South | |

|---|---|---|

| Hard-Pressed Democrats[54] | 48 | |

| Disaffected[54] | 41 | |

| Bystander[54] | 40 | |

| Main Street Republicans[54] | 40 | |

| New Coalition Democrats[54] | 40 | |

| Staunch Conservative[54] | 38 | |

| Post-Modern[54] | 31 | |

| Libertarian[54] | 28 | |

| Solid Liberal[54] | 26 | |

See also

[edit]- Elections in the Southern United States

- Bible Belt

- Politics of the United States

- Blue Dog Democrats

- Boll weevil (politics)

- Conservative Democrat

- Southern Democrat

- Deep South

- Upland South

- History of the Southern United States

- History of the United States Republican Party

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- Political culture of the United States

- Southern Agrarians

- Southernization

- Southern strategy

References

[edit]- ^ Regions and Divisions—2007 Economic Census". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved January 14, 2013.

- ^ Acharya, Avidit; Blackwell, Matthew; Sen, Maya (2018-05-22). Deep Roots. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17674-1.

- ^ Mickey, Robert (2015). Paths Out of Dixie. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-13338-6.

- ^ How to Save a Constitutional Democracy. University of Chicago Press. 2018. p. 22.

- ^ Kuo, Didi (2019). "Comparing America: Reflections on Democracy across Subfields". Perspectives on Politics. 17 (3): 788–800. doi:10.1017/S1537592719001014. ISSN 1537-5927. S2CID 202249318.

- ^ Gibson, Edward L. (2013). "Subnational Authoritarianism in the United States". Boundary Control. pp. 35–71. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139017992.003. ISBN 9780521127332. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "Race, Campaign Politics, and the Realignment in the South". yalebooks.yale.edu. Archived from the original on June 5, 2019. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ Bullock, Charles S.; Hoffman, Donna R.; Gaddie, Ronald Keith (2006). "Regional Variations in the Realignment of American Politics, 1944–2004". Social Science Quarterly. 87 (3): 494–518. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6237.2006.00393.x. ISSN 0038-4941.

The events of 1964 laid open the divisions between the South and national Democrats and elicited distinctly different voter behavior in the two regions. The agitation for civil rights by southern blacks, continued white violence toward the civil rights movement, and President Lyndon Johnson's aggressive leadership all facilitated passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act. [...] In the South, 1964 should be associated with GOP growth while in the Northeast this election contributed to the eradication of Republicans.

- ^ Gaddie, Ronald Keith (February 17, 2012). "Realignment". Oxford Handbooks Online. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195381948.013.0013. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ Stanley, Harold W. (1988). "Southern Partisan Changes: Dealignment, Realignment or Both?". The Journal of Politics. 50 (1): 64–88. doi:10.2307/2131041. ISSN 0022-3816. JSTOR 2131041. S2CID 154860857.

Events surrounding the presidential election of 1964 marked a watershed in terms of the parties and the South (Pomper, 1972). The Solid South was built around the identification of the Democratic party with the cause of white supremacy. Events before 1964 gave white southerners pause about the linkage between the Democratic party and white supremacy, but the 1964 election, passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 altered in the minds of most the positions of the national parties on racial issues.

- ^ Miller, Gary; Schofield, Norman (2008). "The Transformation of the Republican and Democratic Party Coalitions in the U.S.". Perspectives on Politics. 6 (3): 433–50. doi:10.1017/S1537592708081218. ISSN 1541-0986. S2CID 145321253.

1964 was the last presidential election in which the Democrats earned more than 50 percent of the white vote in the United States.

- ^ "The Rise of Southern Republicans – Earl Black, Merle Black". hup.harvard.edu. Harvard University Press. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

When the Republican party nominated Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater—one of the few northern senators who had opposed the Civil Rights Act—as their presidential candidate in 1964, the party attracted many racist southern whites but permanently alienated African-American voters. Beginning with the Goldwater-versus-Johnson campaign more southern whites voted Republican than Democratic, a pattern that has recurred in every subsequent presidential election. [...] Before the 1964 presidential election the Republican party had not carried any Deep South state for eighty-eight years. Yet shortly after Congress passed the Civil Rights Act, hundreds of Deep South counties gave Barry Goldwater landslide majorities.

- ^ a b Issue Evolution. Princeton University Press. 6 September 1990. ISBN 9780691023311. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ^ Miller, Gary; Schofield, Norman (2003). "Activists and Partisan Realignment in the United States". American Political Science Review. 97 (2): 245–60. doi:10.1017/S0003055403000650. ISSN 1537-5943. S2CID 12885628.

By 2000, however, the New Deal party alignment no longer captured patterns of partisan voting. In the intervening 40 years, the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts had triggered an increasingly race-driven distinction between the parties. [...] Goldwater won the electoral votes of five states of the Deep South in 1964, four of them states that had voted Democratic for 84 years (Califano 1991, 55). He forged a new identification of the Republican party with racial conservatism, reversing a century-long association of the GOP with racial liberalism. This in turn opened the door for Nixon's "Southern strategy" and the Reagan victories of the eighties.

- ^ Valentino, Nicholas A.; Sears, David O. (2005). "Old Times There Are Not Forgotten: Race and Partisan Realignment in the Contemporary South". American Journal of Political Science. 49 (3): 672–88. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00136.x. ISSN 0092-5853.

- ^ Ilyana, Kuziemko; Ebonya, Washington (2018). "Why Did the Democrats Lose the South? Bringing New Data to an Old Debate". American Economic Review. 108 (10): 2830–2867. doi:10.1257/aer.20161413. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ Amanda Cox (2012-10-15). "Over the Decades, How States Have Shifted". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "Which States Are in the South?". FiveThirtyEight. 2014-04-30. Retrieved 2017-11-04.

- ^ "History Engine: The Second Reconstruction Act is passed". University of Virginia.

- ^ "Reconstruction vs. Redemption". National Endowment for the Humanities. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ Michael Perman, Pursuit of Unity: A Political History of the American South (2009)

- ^ Sitkoff, Harvard (November 1971). "Harry Truman and the Election of 1948: The Coming of Age of Civil Rights in American Politics". Journal of Southern History. 37 (4): 597–616. doi:10.2307/2206548. JSTOR 2206548.

- ^ Jack Bass and Marilyn W. Thompson, Strom: The Complicated Personal and Political Life of Strom Thurmond (2005).

- ^ Kari Frederickson, The Dixiecrat Revolt and the End of the Solid South, 1932–1968 (2001)

- ^ a b "Dixiecrats". Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "The Emergence of the Civil Rights Movement | Boundless US History". courses.lumenlearning.com. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "Johnson signs Civil Rights Act - Jul 02, 1964 - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ Littlejohn, Jeffrey L., and Charles H. Ford. "Truman and Civil Rights." in Daniel S. Margolies, ed. A Companion to Harry S. Truman (2012) p 287.

- ^ "Sparkman Chosen by Democrats as Running Mate for Stevenson; Senator Hails Party Solidarity". partners.nytimes.com. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "John J. Sparkman - Encyclopedia of Alabama". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ Byron E. Shafer, The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South (2006) ch 6

- ^ "Lester Maddox (1915-2003)". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "School Segregation and Integration - Civil Rights History Project". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ Lawson, Steven F. (1991). "Freedom then, freedom now: The historiography of the civil rights movement". American Historical Review. 96 (2): 456–471. doi:10.2307/2163219. JSTOR 2163219.

- ^ a b c d Trende, Sean (September 9, 2010). "Misunderstanding the Southern Realignment". RealClearPolitics. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ a b Hamby, Peter (December 9, 2014). "The plight of the Southern Democrat". CNN. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Cohn, Nate (December 4, 2014). "Demise of the Southern Democrat Is Now Nearly Complete". The New York Times. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ "Religion and the Presidential Vote | Pew Research Center". People-press.org. 6 December 2004. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- ^ "Exit Polls". CNN. 2004-11-02. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ^ Loftus, Tom (November 9, 2016). "GOP takes Ky House in historic shift". courier-journal.com. Retrieved November 9, 2016.

- ^ Simon, Jeff (December 9, 2016). "How Trump Ended Democrats' 144-Year Winning Streak in One County". CNN. Retrieved January 15, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Joel (9 January 2020). "Virginia becomes Democratic trifecta as legislators are sworn in – Ballotpedia News". Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ^ "Republican Glenn Youngkin wins election for governor in Virginia". PBS NewsHour. 2021-11-03. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ^ Stuart, Tessa (2021-01-06). "Warnock Makes History and Democrats Gain Senate Majority". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ^ "Georgia Election Results 2022: Live Map | Midterm Races by County & District". www.politico.com. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ^ Jones, Bradley (2018-03-20). "1. Trends in party affiliation among demographic groups". Pew Research Center - U.S. Politics & Policy. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ^ "The Chance That Two People Chosen at Random Are of Different Race or Ethnicity Groups Has Increased Since 2010". Census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ^ "Progression of same-sex Marriage in the United States and Worldwide". 2014-11-25. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "Timeline: Same-sex marriage through the years". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "Respect for Marriage Act resonates in Virginia". VPM. 2022-12-16. Retrieved 2023-02-01.

- ^ "The Long Goodbye". The Economist. Retrieved 2018-11-10.

- ^ "Why the South likes Donald Trump". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2017-11-09.

- ^ "States using runoffs for statewide or federal office". FairVote. Retrieved 7 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Beyond Red vs. Blue : Political Typology" (PDF). People-press.org. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

Bibliography

[edit]- Avidit Acharya, Matthew Blackwell & Maya Sen. 2018. Deep Roots: How Slavery Still Shapes Southern Politics. Princeton University Press.

- Bartley, Numan V. The New South, 1945-1980 (1995), broad survey

- David A. Bateman, Ira Katznelson & John S. Lapinski. 2018. Southern Nation: Congress and White Supremacy after Reconstruction. Princeton University Press.

- Billington, Monroe Lee. The Political South in the 20th Century (Scribner, 1975). ISBN 0-684-13983-9.

- Black, Earl, and Merle Black. Politics and Society in the South (1989) excerpt and text search

- Bullock III, Charles S. and Mark J. Rozell, eds. The New Politics of the Old South: An Introduction to Southern Politics (2007) state-by-state coverage excerpt and text search

- Cunningham, Sean P. Cowboy Conservatism: Texas and the Rise of the Modern Right. (2010).

- Grantham. Dewey. The Democratic South (1965)

- Guillory, Ferrel, "The South in Red and Purple: Southernized Republicans, Diverse Democrats," Southern Cultures, 18 (Fall 2012), 6–24.

- Kazin, Michael. What It Took to Win: A History of the Democratic Party (2022)excerpt

- Key, V. O. and Alexander Heard. Southern Politics in State and Nation (1949), a famous classic

- Perman, Michael. Pursuit of Unity: A Political History of the American South (2009)

- Shafer, Byron E., and Richard Johnston. The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South (2009) excerpt and text search

- Steed, Robert P. and Laurence W. Moreland, eds. Writing Southern Politics: Contemporary Interpretations and Future Directions (2006); historiography & scholarly essays excerpts & text search

- Tindall, George Brown. The Emergence of the New South, 1913-1945 (1967), influential survey

- Twyman, Robert W. and David C. Roller, ed. Encyclopedia of Southern History (LSU Press, 1979) ISBN 0-8071-0575-9.

- Woodard, J. David. The New Southern Politics (2006) 445pp

- Woodward, C. Vann. The Origins of the New South, 1877-1913 (1951), a famous classic