Songhai Empire

Zaghai (Songhai) Empire | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1430s–1591 | |||||||||||||||

Territory of the Songhai Empire | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Gao[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | |||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Ayneha | ||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||

• 1464–1492 | Sunni Ali | ||||||||||||||

• 1492–1493 | Sonni Bāru | ||||||||||||||

• 1493–1528 | Askia the Great | ||||||||||||||

• 1529–1531 | Askia Musa | ||||||||||||||

• 1531–1537 | Askia Benkan | ||||||||||||||

• 1537–1539 | Askia Isma'il | ||||||||||||||

• 1539–1549 | Askia Ishaq I | ||||||||||||||

• 1549–1582 | Askia Daoud | ||||||||||||||

• 1588–1592 | Askia Ishaq II | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Early Modern Era | ||||||||||||||

• Songhai state emerges at Gao | c. 7th century | ||||||||||||||

• Independence from Mali Empire | c. 1430s | ||||||||||||||

• Sonni dynasty begins | 1468 | ||||||||||||||

• Askiya dynasty begins | 1493 | ||||||||||||||

| 1599 | |||||||||||||||

• The Nobles moved south to present-day Niger and formed various smaller kingdoms | 1599 | ||||||||||||||

• French depose last Askia of the Dendi | 1901 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| 1550[2] | 800,000 km2 (310,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The Songhai Empire was a state located in the western part of the Sahel during the 15th and 16th centuries. At its peak, it was one of the largest African empires in history. The state is known by its historiographical name, derived from its largest ethnic group and ruling elite, the Songhai people. Sonni Ali established Gao as the empire's capital, although a Songhai state had existed in and around Gao since the 11th century. Other important cities in the kingdom were Timbuktu and Djenné, where urban-centred trade flourished; they were conquered in 1468 and 1475, respectively. Initially, the Songhai Empire was ruled by the Sonni dynasty (c. 1464–1493), but it was later replaced by the Askia dynasty (1493–1591).

During the second half of the 13th century, Gao and the surrounding region had grown into an important trading centre and attracted the interest of the expanding Mali Empire. Mali conquered Gao near the end of the 13th century. Gao remained under Malian command until the late 14th century. As the Mali Empire started disintegrating, the Songhai reasserted control of Gao. Songhai rulers subsequently took advantage of the weakened Mali Empire to expand Songhai rule.

Under the rule of Sonni Ali, the Songhai surpassed the Malian Empire in area, wealth, and power, absorbing vast regions of the Mali Empire. His son and successor, Sonni Bāru, was overthrown by Muhammad Ture, one of his father's generals. Ture, more commonly known as Askia the Great, instituted political and economic reforms throughout the empire.

A series of plots and coups by Askia's successors forced the empire into a period of decline and instability. Askia's relatives attempted to govern the kingdom, but political chaos and several civil wars within the empire ensured the empire's continued decline, particularly during the rule of Askia Ishaq I. The empire experienced a period of stability and a string of military successes during the reign of Askia Daoud.

Askia Ishaq II, the last ruler of the Songhai Empire, ascended to power in a long dynastic struggle following the death of Daoud. In 1590, Al-Mansur took advantage of the recent civil conflict in the empire and sent an army under the command of Judar Pasha to conquer the Songhai and gain control of the trans-Saharan trade routes. The Songhai Empire collapsed after the defeat at the Battle of Tondibi in 1591.

circa 1500.

Name

[edit]The Songhai Empire has been variously translated in texts as Zagha, Zaghai, Zaghaya, Sughai, Zaghay, Zaggan, Izghan, Zaghawa, Zuwagha, Zawagha, Zauge, Azuagha, Azwagha, Sungee, Sanghee, Songhai, Songhay, Sughai, Zanghi, Zingani, Zanj, Zahn, Zaan, Zarai, Dyagha, and possibly Znaga.[3][dubious – discuss]

History

[edit]Early inhabitants

[edit]In ancient times somewhere surmised between the 9th and 3rd centuries BCE, several different groups of people collectively formed the Songhai identity, centered around the developing hub of ancient Kukiya. Among the first people to settle in the region of Gao were the Sorko people, who established small settlements on the banks of Niger. The Sorko fashioned boats and canoes from the wood of the cailcedrat tree, fished and hunted from their ships, and provided water-borne transport for goods and people. Another group of people that moved into the area to live off of Niger's resources were the Gao people. The Gao were hunters and specialized in hunting river animals such as crocodiles and hippopotamus.[citation needed]

The other group known to have inhabited the area were the Do people, farmers who raised crops in the fertile lands bordering the river. Before the 10th century, these early settlers were subjugated by more powerful, horse-riding Songhai speakers, who established control over the area. All these groups gradually began to speak the same language, and they and their country eventually became known as the Songhai.[4]: 49

Gao and Mali

[edit]The earliest dynasty of kings is obscure, and most information about it comes from an ancient cemetery near a village called Saney, close to Gao. Inscriptions on a few of the tombstones in the cemetery indicate that this dynasty ruled in the late 11th and early 12th centuries and that its rulers were given the title of Malik (Arabic for "King"). Other tombstones mention a second dynasty whose rulers bore the title zuwa. Only myth and legend describe the origins of the zuwa. The Tarikh al-Sudan (History of Sudan), written in Arabic around 1655, provides an early history of the Songhai as handed down through oral tradition. It reports that the founder of the Za dynasty was called Za Alayaman (also spelt Dialliaman), who originally came from Yemen and settled in the town of Kukiya.[4]: 60 [5] What happened to the Zuwa rulers is yet to be recorded.[6]

The Sanhaja tribes were among the early people of the Niger Bend region. These tribes rode out of the Sahara Desert and established trading settlements near the Niger. As time passed, North African traders crossed the Sahara and joined the Tuaregs in their settlements. Both groups conducted business with the people living near the river. As trade in the region increased, the Songhai chiefs took control of the profitable trade around what would later become Gao. Trade goods included gold, salt, slaves, kola nuts, leather, dates, and ivory.

By the 10th century, the Songhai chiefs had established Gao as a small kingdom, taking control of the people living along the trade routes. Around 1300, Gao had become prosperous enough to attract the Mali Empire's attention. Mali conquered the city, profited from Gao's trade, and collected taxes from its kings until about the 1430s. Conflict in the Malian homeland made it impossible to maintain control of Gao.[4]: 50–51 Ibn Battuta visited Gao in 1353 when the town was still a part of the Mali Empire. He arrived by boat from Timbuktu on his return journey from visiting the capital of the empire, writing:

Then I travelled to the town of Kawkaw, which is a great town on the Nīl [Niger], one of the finest, biggest, and most fertile cities of the Sūdān. There is much rice there, milk, chickens, fish, and the cucumber, which has no like. Its people conduct their buying and selling with cowries, like the people of Mālī.[7]

Independence

[edit]Following the death of Mansa Sulayman in 1360, disputes over who should succeed him weakened the Mali Empire. The reign of Mari Djata II left the empire in poor financial condition, but the kingdom itself passed intact to Musa II. Mari Djata, Musa's kankoro-sigui, put down a Tuareg rebellion in Takedda and attempted to quell the Songhai rebellion in Gao. While he succeeded in Takedda, he did not re-subjugate Gao.[8] Another round of dynastic instability in the 1380s and 90s likely allowed the Songhai to formalize their independence under Sunni Muhammad Dao.[9] In the 1460s, Sonni Sulayman Dama attacked Méma, the Mali province west of Timbuktu.[4][page needed]

Sonni Ali

[edit]After the death of Sulayman Dama, Sonni Ali reigned from 1464 to 1492. Unlike the previous Songhai kings, Ali sought to honour the traditional religion of his people, taught to him by his mother of the Dendi people. This earned him the reputation of a tyrant by Islamic Scholars.[10] In the late 1460s, he conquered many of the Songhai Empire's neighbouring states, including what remained of the Mali Empire.[citation needed]

During his campaigns for expansion, Ali conquered several territories, repelling attacks from the Mossi to the south and conquering the Dogon people to the north. He annexed Timbuktu in 1468 after the leaders of the town asked him to help overthrow the Tuaregs, who had taken the city following the decline of Mali.[11] When he attempted to conquer the trading town of Djenné, the townspeople resisted his efforts. After a seven-year siege, he was able to starve them into surrender, incorporating the town into his empire in 1473.

The invasion of Sonni Ali and his forces negatively impacted Timbuktu. Many Muslim accounts described him as a tyrant, including the Tarikh al-fattash, which Mahmud Kati wrote. According to The Cambridge History of Africa, the Islamic historian Al-Sa'di expresses this sentiment in describing his incursion on Timbuktu:

Sunni Ali entered Timbuktu, committed gross iniquity, burned and destroyed the town, and brutally tortured many people there. When Akilu heard of the coming of Sonni Ali, he brought a thousand camels to carry the fuqaha of Sankore and went with them to Walata..... The Godless tyrant slaughtered those who remained in Timbuktu and humiliated them.[12]

Sonni Ali created a policy against the scholars of Timbuktu, especially those of the Sankore region who were associated with the Tuareg. With his control of critical trade routes and cities such as Timbuktu, Sonni Ali increased the wealth of the Songhai Empire, which at its height would surpass the wealth of Mali.[13]

Askia the Great

[edit]

Sonni Ali was succeeded by Askia the Great. He organized the territories his predecessor conquered and extended his power to the south and the east. Under his rule, the Songhai military possessed a full-time corps of warriors. Askia is said to have cynical attitudes towards kingdoms lacking professional fighting forces.[14] Al-Sa'di, the chronicler who wrote the Tarikh al-Sudan, compared Askiya's army to that of his predecessor:

"he distinguished between the civilian and the army unlike Sunni Ali [1464–92] when everyone was a soldier."

He opened religious schools, constructed mosques, and opened his court to scholars and poets from throughout the Muslim world. His children went to an Islamic school, and he enforced Islamic practices but did not force religion on his people.[citation needed] Askia completed one of the Five Pillars of Islam by taking a hajj to Mecca, bringing a large amount of gold. He donated some of it to charity and spent the rest on gifts for the people of Mecca to display his empire's wealth. Historians from Cairo said his pilgrimage consisted of "an escort of 500 cavalry and 1000 infantry, and with him he carried 300,000 pieces of gold".[15]

Islam was so important to him that, upon his return, he established more learning centres throughout his empire and recruited Muslim scholars from Egypt and Morocco to teach at the Sankore Mosque in Timbuktu.

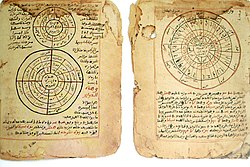

He was interested in astronomy, which led to increased astronomers and observatories in the capital.[16]

Askia initiated multiple military campaigns, including declaring Jihad against the neighbouring Mossi. He did not force them to convert to Islam after subduing them. His army consisted of war canoes, a cavalry, protective armour, iron-tipped weapons, and an organized militia.[citation needed]

He centralized the administration of the empire and established a bureaucracy responsible for tax collection and the administration of justice. He demanded the building of canals to enhance agriculture, eventually increasing trade. He introduced a system of weights and measures and appointed an inspector for each of Songhai's major trading centres.[citation needed]

During his reign, Islam became more entrenched, trans-Saharan trade flourished, and the salt mines of Taghaza were brought within the empire's boundaries.

Decline and Saadian Invasion

[edit]In 1528, Askia's children revolted against him, declaring his son Askia Musa king. Following Musa's overthrow in 1531, the Songhai Empire went into decline. Following the death of Emperor Askia Daoud in 1583, a war of succession weakened the Songhai Empire and split it into two feuding factions.[17]

During this period, Moroccan armies annihilated a Portuguese invasion at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir, but were left on the verge of economic depletion and bankruptcy, as they needed to pay for the defences used to hold off the siege. This led Sultan Ahmad I al-Mansur of the Saadi dynasty in 1591 to dispatch an invasion force south under the eunuch Judar Pasha.[18] The Moroccan invasion of Songhai was mainly to seize and revive the trans-Saharan trade in salt, gold and slaves for their developing sugar industry.[19]: 300 During Askia's reign, the Songhai military consisted of full-time soldiers, but the king never modernized his army. On the other hand, the invading Moroccan army included thousands of arquebusiers and eight English cannons.

Judar Pasha was a Spaniard by birth but had been captured as an infant and educated at the Saadi court. After a march across the Sahara desert, Judar's forces captured, plundered, and razed the salt mines at Taghaza and moved on to Gao. When Emperor Askia Ishaq II (r. 1588–1591) met Judar at the 1591 Battle of Tondibi, Songhai forces, despite vastly superior numbers, were routed by a cattle stampede triggered by the Saadi's gunpowder weapons.[18] Judar proceeded to sack Gao, Timbuktu and Djenné, destroying the Songhai as a regional power. Governing so vast an empire proved too much for the Saadi dynasty. They soon relinquished control of the region, letting it splinter into dozens of smaller kingdoms.[19]: 308

After the empire's defeat, the nobles moved south to an area known today as Songhai in current Niger, where the Sonni dynasty had already settled. They formed smaller kingdoms such as Wanzarbe, Ayerou, Gothèye, Dargol, Téra, Sikié, Kokorou, Gorouol, Karma, Namaro and further south, the Dendi which rose to prominence shortly after.

Organization

[edit]The original Songhai Empire only included the area from the region of Timbuktu to the east of Gao. Provinces were created after a military expansion under Sonni Ali and Askiya, whose territory was divided into three military zones:

- The kurma, where the Balama, the minister of defence of the empire and general-in-chief of the armies in charge of military surveillance of the western provinces, including Mali, was based. The western garrisons were stationed there, and the Balama resided with part of the naval fleet in the port of Kabara. The other important personality was the Kurma Fari, who acted as governor and lived in Timbuktu, the provincial capital.

- The capital city of Gao, where the emperor resided with the central garrisons and part of the fleet commanded by the Hikoy, the admiral of the empire stationed at the port of Gao with more than a thousand ships at its height. It was wheremost large-scale military campaigns started. The emperor was assisted in his military province in the south by the Tondi farma, governor of the province of Hombori, and in the north by the Surgukoy, the Amenokal of Tademekat and chief of the Berbers, in charge of the Saharan provinces and possessing a Camel cavalry army.

- The Dendifari led the eastern province of Dendi. This provincial governor has stationed a garrison in charge of the surveillance of the eastern provinces, including the Hausa kingdoms. The fleet was stationed at the port of Ayorou.

The Songhai Empire at its zenith extended over the current territories of Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Mauritania, Senegal, most other Guinean Coast countries and Algeria. Its influence stretched as far as Cameroon over a vast contiguous ethnolinguistic, cultural, and political space of Mandé peoples, Gur, Dogon, Berbers, Arab, Fula, Wolof, Hausa, Soninke people, Akan people, and Yoruba people.

An elite of Songhai horsemen led this population from nomadic Nilo-Saharan riders of the Neolithic coming from East Africa to mix with the Sorko fishing population and local Niger-Congo agriculturalists of the Niger River.[20]

Culture

[edit]At its peak, Timbuktu became a thriving cultural and commercial centre. Arab, Italian, and Jewish merchants all gathered for trade. A revival of Islamic scholarship took place at the university in Timbuktu.[21]

Economy

[edit]

Overland trade in the Sahel and river trade along the Niger were the primary sources of Songhai wealth. Trade along the West African coast was only possible in the late 1400s.[15] Several dikes were constructed during the reign of Sonni Ali, which enhanced the irrigation and agricultural yield of the empire.[22][23]

Overland trade was influenced by four factors: camels, Berber tribe members, Islam, and the structure of the empire. Gold was readily available in West Africa, but salt was not, so the gold-salt trade was the backbone of overland trade routes in the Sahel. Ivory, ostrich feathers, and slaves were sent north in exchange for salt, horses, camels, cloth, and art. While many trade routes were used, the Songhai heavily used the way through the Fezzan via Bilma, Agades, and Gao.[15]

The Niger River was essential to trade for the empire.[15] Goods were offloaded from camels onto either donkeys or boats at Timbuktu.[15] From there, they were moved along a 500-mile corridor upstream to Djenné or downstream to Gao.[15]

The Julla (merchants) would form partnerships, and the state would protect the merchants and port cities along Niger. Askia Muhammad I implemented a universal system of weights and measures throughout the empire.[24][25][26]

The Songhai economy was based on a clan system. The clan a person belonged to ultimately decided one's occupation. The most common occupations were metalworkers, fishermen, and carpenters. The lower castes mainly consisted of immigrants, who, at times, were provided special privileges and held high positions in society. At the top were noblemen and descendants of the original Songhai people, followed by freemen and traders. At the bottom were prisoners of war and enslaved people who mainly worked in agriculture. The Songhai used slaves more consistently than their predecessors, the Ghana and Mali empires. James Olson described the Songhai labour system as resembling trade unions, with the kingdom possessing craft guilds that consisted of various mechanics and artisans.[27]

Criminal justice

[edit]Criminal justice in Songhai was based mainly, if not entirely, on Islamic principles, especially during the rule of Askia Muhammad. The local qadis were, in addition to this, responsible for maintaining order by following Sharia law under Islamic domination, according to the Qur'an. An additional qadi was noted as a necessity to settle minor disputes between immigrant merchants. Kings usually did not judge a defendant; however, under exceptional circumstances, such as acts of treason, they felt obligated to do so and thus exerted their authority. Results of a trial were announced by the "town crier", and punishment for most trivial crimes usually consisted of confiscation of merchandise or even imprisonment since various prisons existed throughout the Empire.[28]

Qadis worked locally in important trading towns like Timbuktu and Djenné. The king appointed the Qadi and dealt with common-law misdemeanours according to Sharia law. The Qadi also had the power to grant a pardon or offer refuge. The Assara-munitions, or "enforcers", worked like a police commissioner whose sole duty was to execute sentencing. Jurists were mainly composed of representatives of the academic community; professors were often noted as taking administrative positions within the Empire, and many aspired to be qadis.[29]

Government

[edit]The upper classes in society converted to Islam, while the lower classes often continued to follow traditional religions. Sermons emphasized obedience to the king. Timbuktu was the educational capital. Sonni Ali established a system of government under the royal court, later to be expanded by Askia Muhammad, which appointed governors and mayors to preside over local tributary states around the Niger Valley. These local chiefs were still granted authority over their respective domains if they did not undermine Songhai policy.[30] Departmental positions existed in the central government. The hi koy was the fleet commander who performed roles likened to a home affairs minister. Fari Mondzo was the minister of agriculture who administered the state's agricultural estates. The Kalisa farm has been described by historians such as Ki-Zerbo to be the finance minister who supervised the empire's treasury. Korey Farma was also the "minister in charge of White foreigners."[31]

The tax was imposed on peripheral chiefdoms and provinces to ensure Songhai's dominance; in return, these provinces were given almost complete autonomy. Songhai rulers only intervened in the affairs of these neighbouring states when a situation became volatile, usually an isolated incident. Each town was represented by government officials, holding positions and responsibilities similar to today's central bureaucrats.[citation needed]

Under Askia Muhammad, the Empire saw increased centralization. He encouraged learning in Timbuktu by rewarding its professors with larger pensions as an incentive. He also established an order of precedence and protocol and was noted as a nobleman who gave back generously to people experiencing poverty. Under his policies, Muhammad brought much stability to Songhai, and great attestations of this registered organization are still preserved in the works of Maghreb writers such as Leo Africanus, among others.[citation needed]

Religion

[edit]The Sonni dynasty practised Islam while maintaining many aspects of the original Songhai traditions, unlike their successors, the Askiya dynasty.[15] Askia Mohammed I oversaw a complete Islamic revival and made a pilgrimage to Mecca.[15]

Military

[edit]The Songhai armed forces included a navy led by a hikoy (admiral), a cavalry of mounted archers, an infantry, and a camel cavalry. They trained herds of long-horned bulls in the imperial stables to charge at the enemy in battle. Vultures were also used to harass opposing camps.[citation needed]

The emperor was the strategist and commander-in-chief of the military, and the balama acted as minister of defence and army general. The janky was the army corps general, and the wonky were lieutenants in charge of a garrison. The head of the mounted archers was called the tongue farma. The hike was second in the chain of command of the empire and served as its interior minister. He was assisted by two vice-admirals at the ports of Kabara and Ayourou and commanded over a thousand captains, ensuring the rapid movement of troops along the Niger River.[citation needed]

The infantry was led by a general called the nyay hurry (war elephant), and the camel cavalry, called gu, was led by the guy, or cavalry chief. The cavalry mainly consisted of Berbers recruited from the northern provinces.[citation needed]

The Songhai included three military provinces, and an army was stationed in each. It was divided into several garrisons, the kurmina, led by the balama, the central province by the emperor himself and the dendi by the dendi fari. The army of the closest military province was mobilized with that of the emperor. Those remaining on the spot ensured order in the three provinces; the emperor was obliged to be in front of the armed during a war of conquest. The Jinakoy ruled secondary provinces and their lieutenants in the regions of the provinces.[citation needed]

According to Potholm, the Songhai army was dominated by heavy cavalry of "mounted knights outfitted in chain mail and helmets", similar to medieval European armies.[32] The infantry included a force made up primarily of freemen and captives. Swords, arrows and copper or leather shields made up the arsenal of the Songhai infantry. At the Battle of Tondibi, the Songhai army consisted of 30,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry.[33]

Navy

[edit]The Songhai navy dates to the reign of Sonni Ali, who formed a naval force on the Niger River. [34][35][36] The Hi-koi was the commander of the fleet.[37][38] The state had a large network of ports headed by fishermen such as the Goima-Koi in Gao and the Kabara-Farma in Kabara. They were tasked with various duties which included monitoring the state's fleet and the collection of entrance, as well as exit fees.[39] Songhai acquired boats such as the Kanta vessels from the Sorko people who served as tributaries to Songhai.[40] According to a report published by Nordic Africa Institute, the Songhai Kanta "could carry up to 30 tons of goods, i.e. the load capacity of 1,000 men, 200 camels, 300 cattle or a flotilla of 20 regular canoes (Mauny, 1961). Some of these boats had an even greater load capacity of 50 to 80 tons (Tvmowski, 1967).”[a]

List of rulers

[edit]Names and dates taken from John Stewart's African States and Rulers (2005).[41]

Songhai Dias (Kings)

[edit]| Name | Reign Start | Reign End |

|---|---|---|

| Alayaman | c. 837 | c. 849 |

| Za Koi | c. 849 | 861 |

| Takoi | 861 | 873 |

| Akoi | 873 | 885 |

| Ku | 885 | 897 |

| Ali Fai | 897 | 909 |

| Biyai Komai | 909 | 921 |

| Biyai Bei | 921 | 933 |

| Karai | 933 | 945 |

| Yama Karaonia | 945 | 957 |

| Yama Dombo | 957 | 969 |

| Yama Danka Kibao | 969 | 981 |

| Kukorai | 981 | 993 |

| Kenken | 993 | 1005 |

| Za Kosoi | 1005 | 1025 |

| Kosai Dariya | 1025 | 1044 |

| Hen Kon Wanko Dam | 1044 | 1063 |

| Biyai Koi Kimi | 1063 | 1082 |

| Nintasani | 1082 | 1101 |

| Biyai Kaina Kimba | 1101 | 1120 |

| Kaina Shinyunbo | 1120 | 1139 |

| Tib | 1139 | 1158 |

| Yama Dao | 1158 | 1177 |

| Fadazu | 1177 | 1196 |

| Ali Koro | 1196 | 1215 |

| Bir Foloko | 1215 | 1235 |

| Yosiboi | 1235 | 1255 |

| Duro | 1255 | 1275 |

| Zenko Baro | 1275 | 1295 |

| Bisi Baro | 1295 | 1325 |

| Bada | 1325 | 1332 |

Songhai Sunnis (Sheikhs)

[edit]| Name | Reign Start | Reign End |

|---|---|---|

| Ali Konon | 1332 | 1340 |

| Salman Nari | 1340 | 1347 |

| Ibrahim Kabay | 1347 | 1354 |

| Uthman Kanafa | 1354 | 1362 |

| Bar Kaina Ankabi | 1362 | 1370 |

| Musa | 1370 | 1378 |

| Bukar Zonko | 1378 | 1386 |

| Bukar Dalla Boyonbo | 1386 | 1394 |

| Mar Kirai | 1394 | 1402 |

| Muhammad Dao | 1402 | 1410 |

| Muhammad Konkiya | 1410 | 1418 |

| Muhammad Fari | 1418 | 1426 |

| Karbifo | 1426 | 1434 |

| Mar Fai Kolli-Djimbo | 1434 | 1442 |

| Mar Arkena | 1442 | 1449 |

| Mar Arandan | 1449 | 1456 |

| Suleiman Daman | 1456 | 1464 |

Songhai Emperors

[edit]| Name | Reign Start | Reign End |

|---|---|---|

| Sonni Ali | 1464 | 6 November 1492 |

| Sonni Baru | 6 November 1492 | 1493 |

| Askia Muhammad I (First Reign) | 3 March 1493 | 26 August 1528 |

| Askia Musa | 26 August 1528 | 12 April 1531 |

| Askia Mohammad Benkan | 12 April 1531 | 22 April 1537 |

| Askia Ismail | 22 April 1537 | 2 March 1539 |

| Askia Ishaq I | 1539 | 25 March 1549 |

| Askia Daoud | 25 March 1549 | August 1582 |

| Askia Muhammad II (al-Hajj) | August 1582 | 15 December 1586 |

| Muhammad Bani | 15 December 1586 | 9 April 1588 |

| Askia Ishaq II | 9 April 1588 | 14 April 1591 |

Songhai Emperors (ruled in exile from Dendi)

[edit]| Name | Reign Start | Reign End |

|---|---|---|

| Muhammad Gao | 14 April 1591 | 1591 |

| Nuh | 1591 | 1599 |

| Harun | 1599 | 1612 |

| Al-Amin | 1612 | 1618 |

| Dawud II | 1618 | 1635 |

| Ismail | 1635 | 1640 |

| Samsou-Béri | 1761 | 1779 |

| Hargani | 1779 | 1793 |

| Samsou Keïna | 1793 | 1798 |

| Fodi Maÿroumfa | 1798 | 1805 |

| Tomo | 1805 | 1823 |

| Bassarou Missi Izé | 1823 | 1842 |

| Boumi (Askia Kodama Komi) | 1842 | 1845 |

See also

[edit]- Za dynasty

- Sonni dynasty

- Askiya dynasty

- Saadi dynasty

- Mali Empire

- Dendi Kingdom

- Songhai languages

- Songhai country

- Songhaiborai

Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Bethwell A. Ogot, Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century, (UNESCO Publishing, 2000), 303.

- ^ Taagepera 1979, pp. 497.

- ^ Meyerowitz, Eva (1972). "The Origins of the "Sudanic" Civilization". Anthropos. 67 (1/2): 161–175. JSTOR 40458020.

- ^ a b c d David C. Conrad (1 November 2009). Empires of Medieval West Africa. Chelsea House Pub. ISBN 1604131640.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. 35.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 300.

- ^ Stride, George T.; Ifeka, Caroline (1 January 1971). Peoples and Empires of West Africa; West Africa in History, 1000–1800. Holmes & Meier Pub. ISBN 0841900698.

- ^ Person, Yves (1981). "Nyaani Mansa Mamudu et la fin de l 'empire du Mali". Le sol, la parole et l'écrit: Mélanges en hommage à Raymond Mauny, Tome II. Paris: Société française d'histoire d'outre-mer. p. 616. Retrieved 13 November 2024.

- ^ "Sonni Ali". Britannica.

- ^ Sonni ʿAlī.(2007). Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ The Cambridge History of Africa, Vol 5: University Press, 1977, pp 421

- ^ Daniel, McCall; Norman, Bennett (1971). Aspects of West African Islam. Boston University, African Studies Center. pp. 42–45.

- ^ Thornton, John K.. Warfare in Atlantic Africa, 1500-1800 (Warfare and History) (Kindle Locations 871-872). Taylor and Francis. Kindle Edition.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Willard, Alice (1993-04-01). "Gold, Islam and Camels: The Transformative Effects of Trade and Ideology". Comparative Civilizations Review. 28 (28): 88–89. ISSN 0733-4540.

- ^ Meri, Josef W. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: L-Z, index. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780415966924.

- ^ Loimeier, Roman (2013). Muslim Societies in Africa: A Historical Anthropology. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780253007971. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Kingdoms of Africa - Niger". www.historyfiles.co.uk. Retrieved 2020-01-23.

- ^ a b Abitbol, M. (1992). "The end of the Songhay empire". In Ogot, B. A. (ed.). General History of Africa vol. V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. UNESCO. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Stoller, Paul (15 June 1992), The Cinematic Griot: The Ethnography of Jean Rouch, University of Chicago Press, p. 56, ISBN 9780226775463, retrieved 2021-06-03

- ^ Owen Jarus (21 January 2013). "Timbuktu: History of Fabled Center of Learning". Live Science.

- ^ "Songhai Empire". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2021-08-15.

- ^ Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa (1998), p. 79

- ^ Shillington, Kevin (2013). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Routledge. p. 1589. ISBN 9781135456702.

- ^ Hunwick, John (1976). "Songhay, Borno, and Hausaland in the sixteenth century," in The History of West Africa. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 264–301.

- ^ Festus, Ugboaja Ohaegbulam (1990). Towards an Understanding of the African Experience from Historical and Contemporary Perspective. University Press of America. p. 79. ISBN 9780819179418.

- ^ Olson, James Stuart. The Ethnic Dimension in American History. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc., 1979

- ^ Lady Lugard 1997, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Dalgleish 2005.

- ^ Iliffe 2007, pp. 72.

- ^ Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa (1998), p. 81-82

- ^ Potholm, Christian P. (2010). Winning at War: Seven Keys to Military Victory Throughout History. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 107. ISBN 9781442201309.

- ^ Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa (1998), p. 83

- ^ Wiesner-Hanks, Merry E. (2005). The Medieval & Early Modern World. Oxford University Press. p. 104. ISBN 9780195176728.

- ^ Hogue, W. Lawrence (2012). The African American Male, Writing, and Difference: A Polycentric Approach to African American Literature, Criticism, and History. State University of New York Press. p. 258. ISBN 9780791487006.

- ^ Del Testa, David W. (2014). Government Leaders, Military Rulers and Political Activists. Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 9781135975661.

- ^ International Scientific Committee for the drafting of a General History of Africa (1984). General History of Africa: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. UNESCO Publishing. p. 197. ISBN 9789231017100.

- ^ Maiga, Hassimi Oumarou (2009). Balancing Written History with Oral Traditions: The Legacy of the Songhoy People. Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 9781135227036.

- ^ a b Tvedten, Inge; Hersoug, Bjørn (1992). Fishing for Development: Small-scale Fisheries in Africa. Nordic Africa Institute. p. 57. ISBN 9789171063274.

- ^ Hunwick 2003, p. xxxi.

- ^ Stewart, John (2005). African States and Rulers. London: McFarland. p. 206. ISBN 0-7864-2562-8.

Sources

[edit]- Dalgleish, David (April 2005). "Pre-Colonial Criminal Justice In West Africa: Eurocentric Thought Versus Africentric Evidence" (PDF). African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies. 1 (1). Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- Haskins, James; Benson, Kathleen; Cooper, Floyd (1998). African Beginnings. New York City: HarperCollins. pp. 48 Pages. ISBN 0-688-10256-5.

- Iliffe, John (2007). Africans: The History of a Continent. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68297-8.

- Hunwick, John O. (25 March 2003). Timbuktu and the Songhay Empire: Al-Sadi's Tarikh al-Sudan down to 1613 and other contemporary documents. Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 90-04-12822-0.

- Lady Lugard, Flora Louisa Shaw (1997). "Songhay Under Askia the Great". A tropical dependency: an outline of the ancient history of western Sudan with an account of the modern settlement of northern Nigeria / [Flora S. Lugard]. Black Classic Press. ISBN 0-933121-92-X.

- Malio, Thomas A. Hale. by The epic of Askia Mohammed / recounted by Nouhou (1990). Scribe, griot, and novelist: narrative interpreters of the Songhay Empire. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-0981-2.

- Taagepera, Rein (1979). Social Science History, Vol. 3, No. 3/4 "Size and Duration of Empires: Growth-Decline Curves, 600 B.C. to 600 A.D.". Durham: Duke University Press.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F.P., eds. (2000). Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa. New York, NY: Marcus Weiner Press. ISBN 1-55876-241-8.

- Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa (1998). UNESCO General History of Africa, Vol. IV, Abridged Edition: Africa from the Twelfth to the Sixteenth Century. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520066991.

Further reading

[edit]- Isichei, Elizabeth. A History of African Societies to 1870. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. Print.

- Shillington, Kevin. History of Africa . 2nd . NY: Macmillan, 2005. Print.

- Cissoko, S. M., Timbouctou et l'empire songhay, Paris 1975.

- Lange, D., Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa, Dettelbach 2004 (the book has a chapter titled "The Mande factor in Gao history", pp. 409–544).

- Gomez, Michael A., African Dominion: A New History of Empire in Early and Medieval West Africa. Princeton University Press, 2018.

External links

[edit]- The Story of Africa: Songhay — BBC World Service

- Askiyah's Questions and al-Maghili's Answers An essay about the rule of the Songhai Empire from the 15th century. (in English and Arabic)