Sodium vapor process

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2008) |

The sodium vapor process (occasionally referred to as yellowscreen) is a photochemical film technique for combining actors and background footage. It originated in the British film industry in the late 1950s and was used extensively by Walt Disney Productions in the 1960s and 1970s as an alternative to the more common bluescreen process. Wadsworth E. Pohl is credited with the invention or development of both of these processes (Patent US3133814A[1]), and received (with Ub Iwerks and Petro Vlahos) an Academy Award in 1965 for the sodium vapor process as used in the film Mary Poppins.[2][3][4][5]

Description

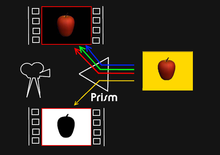

[edit]The process is not very complicated in principle. An actor is filmed performing in front of a white screen that is lit with powerful sodium vapor lights. This light has a narrow color spectrum, that falls neatly into a chromatic notch between the various color sensitivity layers of color film. In this way the yellow color does not register on the red, green, or blue layers.[5] This allows the complete range of colors to be used, not only in costumes, but also in makeup and props. A camera with a beam-splitter prism is used to expose two separate film elements. The main element is the regular color negative film insensitive to sodium light and the other a fine-grain black-and-white film that is extremely sensitive to the specific wavelength produced by the sodium vapor.[5]

This second film element is used to create a matte, as well as a counter-matte, for use during compositing on an optical printer. These complementary mattes allow the various image elements to be cleanly isolated, so that as they are re-exposed onto a single fresh piece of negative, one at a time and in jigsaw fashion, the various images do not show through one another (as they would using simple double exposure). Acquiring the matte film element (as a first-generation original) at the same time as the live action makes a much better fit during optical printing, because it requires fewer separate, duplicate film generations than does bluescreen (though both processes degrade the image and introduce more "error" to the resulting matte) in the process of achieving sufficiently dense mattes. This increased accuracy ultimately renders the matte "lines" almost invisible, though as with bluescreen, its use may be signaled by hard separation or mismatched coloration and contrast between elements, or in this case, a telltale white/yellow fringe.[2]

History

[edit]Disney made one sodium vapor camera. The camera was a retired Technicolor three-strip camera modified to use two films and used normal lenses for the conventional 1.85:1 aspect ratio.[citation needed] First developed in 1932, Technicolor three-strip cameras ran three rolls of black-and-white film past a beam splitter and a prism to film three strips of film, one for each primary color. In 1952, Eastman Kodak introduced its color negative film, Eastmancolor, which led to Hollywood's discontinuation of Technicolor cameras in 1954.

At the time of its use, the sodium process yielded cleaner results than did bluescreen, which was subject to noticeable color spill (a blue tint around the edges of the matte). The increased accuracy allowed for the compositing of materials with finer detail, such as hair or Mary Poppins' veiled hat. It was also useful that the "sodium yellow" light (and its removal via the matte) had a negligible effect on human skin tones.[2] As the bluescreen process improved, the sodium vapor process was abandoned; its screen and lamps monopolizing huge studios and incurring a higher cost.[citation needed] It was also reported that only three of the required prisms were produced.[6]

The first use of the process was in the J. Arthur Rank Organisation's Plain Sailing in 1956.[2] It was used in Disney's short Donald and the Wheel,[7] and the films The Parent Trap and Mary Poppins. It was also used for the Ray Harryhausen film First Men In The Moon, produced by Columbia Pictures. This was the only film Ray made in Cinemascope. He needed an alternate method of getting his stop motion characters together onto screen as his traditional methods did not fit the anamorphic lens process. Alfred Hitchcock's The Birds (produced by Universal Studios) used yellow screen, under the direction of Disney animator Ub Iwerks, in traveling matte shots with birds' rapidly fluttering wings.

The process was used in the 1970s for scenes in Island at the Top of the World, Gus, The Apple Dumpling Gang, Bedknobs and Broomsticks, Freaky Friday, Escape to Witch Mountain, Pete's Dragon, and The Black Hole. The last known use of the process was in the 1990 film Dick Tracy.[8]

Modern recreation

[edit]On April 7, 2024, production studio Corridor Digital published a video showcasing a modern implementation of the sodium vapor process using a custom filter setup developed by Paul Debevec.[6]

This setup had the following steps:

- Use Low Pressure Sodium lights outputting light at a spectrum of 589 nanometers onto a white backdrop screen.

- Illuminate the subject in front of the screen using LED lighting, making sure that none of the 589 nm light spills onto the subject.

- Take a normal beam splitter, and put a casing around it where two sides have light filters: One Notch-Reject filter, one Bandpass filter. Using two cameras, point one at each filter.

- This will film a foreground and a matte. When editing, start with a background image. Subtract the matte. Then edit the foreground image to remove everything that isn't part of the matte. Then add the edited foreground to the edited background on top of the subtracted area. [1]

Further reading

[edit]- US3095304A, Petro, Vlahos, "Composite photography utilizing sodium vapor illumination", issued 1963-06-25

- This Invention Made Disney MILLIONS, but Then They LOST It! (video). Corridor Crew. 8 April 2024. Archived from the original on 9 April 2024.

References

[edit]- ^ Patent US3133814A https://patents.google.com/patent/US3133814?oq=WADSWORTH+E.+POHL

- ^ a b c d Brosnan, John (1976). Movie Magic. New American Library. p. 111.

- ^ Smith, Alvy Ray (August 15, 1995). "Alpha and the History of Digital Compositing" (PDF). Retrieved January 8, 2012.

- ^ "Academy Awards Database". Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved January 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c Jackman, John (2007). Bluescreen compositing: a practical guide for video & moviemaking. Focal Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-57820-283-6.

- ^ a b Northrup, Ryan (2024-04-10). "VFX Artists Recreate Groundbreaking Disney Special Effect Lost For 58 Years". ScreenRant. Retrieved 2024-04-12.

- ^ Walt Disney's “Donald and The Wheel” (1961) | Cartoon Research

- ^ Cook, Peter (23 August 2011). "Matte Shot – a tribute to Golden Era special fx". Retrieved January 8, 2012.