Christian left

| Part of a series on |

| Progressivism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

The Christian left is a range of Christian political and social movements that largely embrace social justice principles and uphold a social doctrine or social gospel based on their interpretation of the teachings of Christianity. Given the inherent diversity in international political thought, the term Christian left can have different meanings and applications in different countries. While there is much overlap, the Christian left is distinct from liberal Christianity, meaning not all Christian leftists are liberal Christians and vice versa.

In the United States, the Christian left usually aligns with modern liberalism and progressivism, using the social gospel to achieve better social and economic equality.[1] Christian anarchism, Christian communism, and Christian socialism are subsets of the socialist Christian left. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, authors of the Communist Manifesto, both had Christian upbringings; however, neither were devout Christians.[2][3]

Terminology

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2018) |

As with any section within the left–right political spectrum, a label such as Christian left represents an approximation, including within it groups and persons holding many diverse viewpoints. The term left-wing might encompass a number of values, some of which may or may not be held by different Christian movements and individuals. As the unofficial title of a loose association of believers, it provides a clear distinction from the more commonly known Christian right, or religious right, and from its key leaders and political views. The Christian left does not hold the notion that left-leaning policies, whether economic or social, stand in apparent contrast to Christian beliefs.

The most common religious viewpoint that might be described as left-wing is social justice, or care for impoverished and oppressed minority groups. Supporters of this trend might encourage universal health care, welfare provisions, subsidized education, foreign aid, and affirmative action for improving the conditions of the disadvantaged. With values stemming from egalitarianism, adherents of the Christian left consider it part of their religious duty to take actions on behalf of the oppressed. Matthew 25:31–46, among other verses, is often cited to support this view. As nearly all major religions contain some kind of requirement to help others,[4] adherents of various religions have cited social justice as a movement in line with their faith.[5] The term social justice was coined in the 1840s by Luigi Taparelli, an Italian Catholic scholar of the Society of Jesus, who was inspired by the writings of Thomas Aquinas.[6] The Christian left holds that social justice, renunciation of power, humility, forgiveness, and private observation of prayer (as in Matthew 6:5–6) as opposed to publicly mandated prayer, are mandated by the Gospel. The Bible contains accounts of Jesus repeatedly advocating for the poor and outcast over the wealthy, powerful, and religious. The Christian left maintains that such a stance is relevant and important. Adhering to the standard of "turning the other cheek", which they believe supersedes the Old Testament law of "an eye for an eye", the Christian left sometimes hearkens towards pacifism in opposition to policies advancing militarism.[7]

The medieval Waldensians sect had a leftist character.[8] Some among the Christian left,[9] as well as some non-religious socialists, find support for anarchism, communism, and socialism in the Gospels, for example Mikhail Gorbachev citing Jesus as "the first socialist".[10] The Christian left is a broad category that includes Christian socialism, as well as Christians who would not identify themselves as socialists.

History

[edit]Early years

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2012) |

For much of the early history of anti-establishment leftist movements, such as socialism and communism, which was highly anti-clerical in the 19th century, some established churches were led by clergy who saw revolution as a threat to their status and power. The church was sometimes seen as part of the establishment. Revolutions in the United States, France and Russia were in part directed against the established churches, or rather their leading clergy, and instituted a separation of church and state.

In the 19th century, some writers and activists developed the school of thought of Christian socialism, which infused socialist principles into Christian theology and praxis. Early socialist thinkers such as Robert Owen, Henri de Saint-Simon based their theories of socialism upon Christian principles. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels reacted against these theories by formulating a secular theory of socialism in The Communist Manifesto.

Alliance of the left and Christianity

[edit]Starting in the late 19th century and early 20th century,[citation needed] some began to take on the view that genuine Christianity had much in common with a leftist perspective. From St. Augustine of Hippo's City of God through St. Thomas More's Utopia, major Christian writers had expounded upon views that socialists found agreeable. Of major interest was the extremely strong thread of egalitarianism in the New Testament. Other common leftist concerns such as pacifism, social justice, racial equality, human rights, and the rejection of excessive wealth are also expressed strongly in the Bible. In the late 19th century, the Social Gospel movement arose (particularly among some Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists and Baptists in North America and Britain,) which attempted to integrate progressive and socialist thought with Christianity to produce a faith-based social activism, promoted by movements such as Christian socialism. In the United States during this period, Episcopalians and Congregationalists generally tended to be the most liberal, both in theological interpretation and in their adherence to the Social Gospel. In Canada, a coalition of liberal Congregationalists, Methodists, and Presbyterians founded the United Church of Canada, one of the first true Christian left denominations. Later in the 20th century, liberation theology was championed by such writers as Gustavo Gutierrez and Matthew Fox.

Christians and workers

[edit]To a significant degree, the Christian left developed out of the experiences of clergy who went to do pastoral work among the working class, often beginning without any social philosophy but simply a pastoral and evangelistic concern for workers. This was particularly true among the Methodists and Anglo-Catholics in England, Father Adolph Kolping in Germany and Joseph Cardijn in Belgium.

Christian left and campaigns for peace and human rights

[edit]Some Christian groups were closely associated with the peace movements against the Vietnam War as well as the 2003 Invasion of Iraq. Religious leaders in many countries have also been on the forefront of criticizing any cuts to social welfare programs. In addition, many prominent civil rights activists were religious figures.

In the United States

[edit]In the United States, members of the Christian Left come from a spectrum of denominations: Peace churches, elements of the Protestant mainline churches, Catholicism, and some evangelicals.[11]

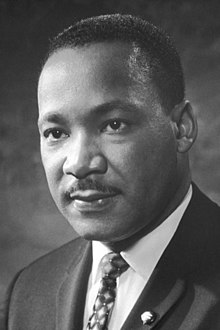

Martin Luther King Jr.

[edit]

Martin Luther King Jr. was an American Baptist minister and activist who became the most visible spokesman and leader in the civil rights movement from 1955 until his assassination in 1968. Inspired by his Christian beliefs and the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi, he led targeted, nonviolent resistance against Jim Crow laws and other forms of discrimination. In 1957, King and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The group was created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct nonviolent protests in the service of civil rights reform. The group was inspired by the crusades of evangelist Billy Graham, who befriended King, as well as the national organizing of the group in Friendship, founded by King allies Stanley Levison and Ella Baker. King led the SCLC until his death.

As a Christian minister, King's main influence was Jesus Christ and the Christian gospels, which he would almost always quote in his religious meetings, speeches at church, and in public discourses. King's faith was strongly based in Jesus' commandment of loving your neighbor as yourself, loving God above all, and loving your enemies, praying for them and blessing them. His nonviolent thought was also based in the injunction to turn the other cheek in the Sermon on the Mount, and Jesus' teaching of putting the sword back into its place (Matthew 26:52). In his famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail", King urged action consistent with what he describes as Jesus' "extremist" love, and also quoted numerous other Christian pacifist authors, which was very usual for him. In another sermon, he stated:

Before I was a civil rights leader, I was a preacher of the Gospel. This was my first calling and it still remains my greatest commitment. You know, actually all that I do in civil rights I do because I consider it a part of my ministry. I have no other ambitions in life but to achieve excellence in the Christian ministry. I don't plan to run for any political office. I don't plan to do anything but remain a preacher. And what I'm doing in this struggle, along with many others, grows out of my feeling that the preacher must be concerned about the whole man.

Beliefs

[edit]Homosexuality

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2018) |

The Christian left generally approaches homosexuality differently from some other Christian political groups. This approach can be driven by focusing on issues differently despite holding similar religious views, or by holding different religious ideas. Those in the Christian left who have similar ideas as other Christian political groups but a different focus may view Christian teachings on certain issues, such as the Bible's prohibitions against killing or criticisms of concentrations of wealth, as far more politically important than Christian teachings on social issues emphasized by the religious right, such as opposition to homosexuality. Others in the Christian left have not only a different focus on issues from other Christian political groups, but different religious ideas as well.

For example, some members of the Christian left may consider discrimination and bigotry against homosexuals to be immoral, but they differ on their views towards homosexual sex. Some believe homosexual sex to be immoral but unimportant compared with issues relating to social justice, or even matters of sexual morality involving heterosexual sex. Others assert that some homosexual practices are compatible with the Christian life. Such members believe common biblical arguments used to condemn homosexuality are misinterpreted, and that biblical prohibitions of homosexual practices are actually against a specific type of homosexual sex act, i.e. pederasty, the sodomizing of young boys by older men. Thus, they hold biblical prohibitions to be irrelevant when considering modern same-sex relationships.[12][13][14][15]

Consistent life ethic

[edit]A related strain of thought is the (Catholic and progressive evangelical) consistent life ethic, which sees opposition to capital punishment, militarism, euthanasia, abortion and the global unequal distribution of wealth as being related. It is an idea with certain concepts shared by Abrahamic religions as well as some Buddhists, Hindus, and members of other religions. The late Cardinal Joseph Bernardin of Chicago developed the idea for the consistent life ethic in 1983.[16] Sojourners is particularly associated with this strand of thought.[17][18]

Liberation theology

[edit]Liberation theology is a theological tradition that emerged in the developing world, primarily in Latin America.[19] Since the 1960s, Catholic thinkers have integrated left-wing thought and Catholicism, giving rise to Liberation theology. It arose at a time when Catholic thinkers who opposed the despotic leaders in Southern and Central America allied themselves with the communist opposition. However, it developed independently of and roughly simultaneously with Black theology in the U.S. and should not be confused with it.[20] The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith decided that while liberation theology is partially compatible with Catholic social teaching, certain Marxist elements of it, such as the doctrine of perpetual class struggle, are against Church teachings.

Political parties

[edit]Active

[edit]| State | Party | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Christian Democratic Party | |||

| Christian Democracy | |||

| 360 Association, AreaDem, Olivists, Reformist Base, Social Christians, Teodem, The Populars, and Veltroniani | Factions within the Democratic Party | ||

| Democratic Centre | |||

| Solidary Democracy | |||

| Christian Union | Economic left | ||

| Sandinista National Liberation Front | |||

| AGROunia | Agrarian and nationalist Christian left | ||

| Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland | |||

| Social Democratic Party | |||

| Religious Social Democrats of Sweden | Faction within the Swedish Social Democratic Party | ||

| Christian Social Party | |||

| Christians on the Left | Faction within the Labour Party | ||

| American Solidarity Party | Economic left | ||

| Prohibition Party | |||

| Christian Democratic Party of Uruguay | |||

Defunct

[edit]| State | Party | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humanist Democratic Centre | Factions only | ||

| Co-operative Commonwealth Federation | Merged into the New Democratic Party | ||

| Citizen Left | |||

| Christian Democratic Union | Until 1989 | ||

| Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy | Merged into the Democratic Party | ||

| Italian People's Party | Merged into Democracy is Freedom – The Daisy | ||

| Evangelical People's Party | Merged into GroenLinks | ||

| Political Party of Radicals | |||

See also

[edit]Early Christianity

[edit]Movements and denominations

[edit]A number of movements of the past had similarities to today's Christian left:

- Anabaptists

- Catholic Worker Movement

- Christian Church (Disciples of Christ)

- Congregationalists

- Diggers

- Emergent Church

- Episcopal Church (United States)

- Fifth Monarchists

- German Peasants' War

- Heretical movements such as the Cathars

- Jesus movement

- Liberation theology

- Lollard

- Peace churches

- Progressive National Baptist Convention

- Quakers

- Role of Christians in the Peasants' Revolt in England, see Lollard priest John Ball

- Seventh-day Adventist Church

- Unitarianism

- United Church of Christ

- Universalism

- Waldenses

Other

[edit]- Christian democracy

- Christian libertarianism

- Christian pacifism

- Christian politics

- Christian socialism

- Evangelical left

- Homosexuality and Christianity

- International League of Religious Socialists

- Jewish left

- Left-wing populism

- Liberal Christianity

- Pacifism

- Political Catholicism

- Progressive Christianity

- Progressive Muslim vote

- Religion and abortion

- Religious communism

- Religious socialism

- Religious Society of Friends

- Social Gospel

- Spiritual left

References

[edit]- ^ Stanton, Zack (25 February 2021). "You Need to Take the Religious Left Seriously This Time". Politico. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ Boer, Roland. "Engels and revolutionary religion". culturematters.org.uk. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "Religion as Opium of the People". Learn Religions. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ "The "Golden Rule" (a.k.a. Ethics of Reciprocity)". Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Leilah Danielson, Marian Mollin, Doug Rossinow, The Religious Left in Modern America: Doorkeepers of a Radical Faith, Springer, USA, 2018, p. 27

- ^ "The FAQs: What Christians Should Know About Social Justice". 17 August 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ Damon, Linker (31 March 2014). "Why Christianity demands pacifism". The Week. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- ^ von Kuehnelt-Leddihn, E. (1974). Leftism: from de Sade and Marx to Hitler and Marcuse. Arlington House. ISBN 978-0-87000-143-7. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ John Cort, Christian Socialism (1988) ISBN 0-88344-574-3, pp. 32.

- ^ "Mikhail S. Gorbachev Quotes". Brainyquote.com. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ Hall, Charles F. (September 1997). "The Christian Left: Who Are They and How Do They Differ from the Christian Right?". Review of Religious Research. 39: 31–32. doi:10.2307/3512477. JSTOR 3512477.

- ^ Why TCPC Advocates Equal Rights for Gay and Lesbian People Archived 12 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Equality for Gays and Lesbians – Christian Alliance for Progress". 1 December 2005. Archived from the original on 1 December 2005.

- ^ Bible & Homosexuality Home Page Archived 24 February 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Pflagdetroit.org (11 December 1998). Retrieved on 2013-08-24.

- ^ [1] Archived 21 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Bernardin, Joseph. Consistent ethics of life 1988, Sheed and Ward, p. v

- ^ McKanan, Dan (November 2011). Prophetic Encounters: Religion and the American Radical Tradition. Beacon Press. ISBN 9780807013168.

- ^ Dorrien, Gary (25 March 2009). Social Ethics in the Making: Interpreting an American Tradition. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781444305777.

- ^ Løland, Ole Jakob (July 2021). Usarski, Frank (ed.). "The Solved Conflict: Pope Francis and Liberation Theology" (PDF). International Journal of Latin American Religions. 5 (2). Berlin: Springer Nature: 287–314. doi:10.1007/s41603-021-00137-3. eISSN 2509-9965. ISSN 2509-9957.

- ^ "Prophets of a Modern Era: An Introduction to Liberation Theology | Koinonia Revolution". Archived from the original on 27 October 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Young, Shawn David (2015). Gray Sabbath: Jesus People USA, the Evangelical Left, and the Evolution of Christian Rock. New York: Columbia University Press.

External links

[edit]- American Socialist Voter at the Wayback Machine (archived 2009-06-12) – Educational and interactive networking (non-partisan)

- Anglo-Catholic Socialism

- CrossLeft: Balancing the Christian Voice, Organizing the Christian Left at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2008-09-19)

- The Christian Leftist: The 'Religious' 'Right' Is Neither

- Religious Movements Homepage: Call to Renewal: Christians for a New Political Vision

- Points of Unity for Social Democratic Branches within the USA at archive.today (archived 2008-08-31)

- Religion and Socialism Commission of the Democratic Socialists of America

- Socialism and Faith Commission of the Socialist Party USA at the Wayback Machine (archived 2007-07-02)

- Sojourners Magazine

- Social Redemption

- The Center for Progressive Christianity at the Wayback Machine (archived 2006-12-06)

- The Christian Alliance for Progress

- Known Author – discussion forum for liberal Christians

- The Bible on the Poor: Or Why God is a Liberal