GSK plc

Logo since 9 June 2022 | |

Head office in Brentford, London with the former GlaxoSmithKline logo, taken on 30 July 2007 | |

| Formerly | GlaxoSmithKline (2000–2022) |

|---|---|

| Company type | Public limited company |

| Industry | |

| Predecessors |

|

| Founded | 27 December 2000 |

| Headquarters | London, England, UK |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | 70,000 (2024)[2] |

| Subsidiaries | |

| Website | www |

GSK plc (an acronym from its former name GlaxoSmithKline plc) is a British multinational pharmaceutical and biotechnology company with headquarters in London.[3][4] It was established in 2000 by a merger of Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham,[n 1] which was itself a merger of a number of pharmaceutical companies around the Smith, Kline & French firm.

GSK is the tenth largest pharmaceutical company and No. 294 on the 2022 Fortune Global 500, ranked behind other pharmaceutical companies China Resources, Sinopharm, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer, Roche, AbbVie, Novartis, Bayer, and Merck Sharp & Dohme.[5]

The company has a primary listing on the London Stock Exchange and is a constituent of the FTSE 100 Index. As of February 2024, it had a market capitalisation of £69 billion, the eighth largest on the London Stock Exchange.[6]

The company developed the first malaria vaccine, RTS,S, which it said in 2014, it would make available for five per cent above cost.[7] Legacy products developed at GSK include several listed in the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, such as amoxicillin, mercaptopurine, pyrimethamine and zidovudine.[8]

In 2012, under prosecution by the United States Department of Justice (DoJ) based on combined investigations of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS-OIG), FDA and FBI, primarily concerning sales and marketing of the drugs Avandia, Paxil and Wellbutrin, GSK pleaded guilty to promotion of drugs for unapproved uses, failure to report safety data and kickbacks to physicians in the United States and agreed to pay a US$3 billion (£1.9bn) settlement. It was the largest health-care fraud case to date in the US and the largest settlement in the pharmaceutical industry.[9]

History

[edit]Glaxo Wellcome

[edit]

Glaxo

[edit]Joseph Nathan and Co. was founded in 1873, as a general trading company in Wellington, New Zealand, by a Londoner, Joseph Edward Nathan.[10] In 1904, it began producing a dried-milk baby food from excess milk produced on dairy farms near Bunnythorpe. The resulting product was first known as Defiance, then as Glaxo (from lacto), and sold with the slogan "Glaxo builds bonnie babies."[11][12]: 306 [13] The Glaxo Laboratories sign is still visible on what is now a car repair shop on the main street of Bunnythorpe. The company's first pharmaceutical product, released in 1924, was vitamin D.[12]: 306

Glaxo Laboratories was incorporated as a distinct subsidiary company in London in 1935.[14] Joseph Nathan's shareholders reorganised the group's structure in 1947, making Glaxo the parent[15] and obtained a listing on the London Stock Exchange.[16] Glaxo acquired Allen & Hanburys in 1958. The Scottish pharmacologist David Jack was hired as a researcher for Allen & Hanburys a few years after Glaxo took it over; he went on to lead the company's research and development (R&D) until 1987.[12]: 306 After Glaxo bought Meyer Laboratories in 1978, it began to play an important role in the US market. In 1983, the American arm, Glaxo Inc., moved to Research Triangle Park (US headquarters/research) and Zebulon (US manufacturing) in North Carolina.[13]

Burroughs Wellcome

[edit]Burroughs Wellcome & Company was founded in 1880, in London by the American pharmacists Henry Wellcome and Silas Burroughs.[17] The Wellcome Tropical Research Laboratories opened in 1902. In the 1920s, Burroughs Wellcome established research and manufacturing facilities in Tuckahoe, New York,[18]: 18 [19][20] which served as the US headquarters until the company moved to Research Triangle Park in North Carolina in 1971.[21][22] The Nobel Prize winning scientists Gertrude B. Elion and George H. Hitchings worked there and invented drugs still used many years later, such as mercaptopurine.[23] In 1959, the Wellcome Foundation bought Cooper, McDougall & Robertson Inc to become more active in animal health.[13]

When Burroughs Wellcome decided to move its headquarters, the company selected Paul Rudolph to design its new building.[24] The Elion-Hitchings Building "was celebrated worldwide when it was built," according to Paul Rudolph Heritage Foundation president Kelvin Dickinson. Alex Sayf Cummings of Georgia State University wrote in 2016, that the "iconic building helped define the image of RTP," saying, "Love it or hate it, Rudolph's design remains an impressively audacious creative gesture and an important part of the history of both architecture and Research Triangle Park."[25] United Therapeutics, which bought the building in 2012, announced plans in 2020, to tear it down.[25]

Merger

[edit]Glaxo and Wellcome merged in 1995, to form Glaxo Wellcome plc.[26][12] The merger was then considered the biggest in the UK corporate history.[17] Glaxo Wellcome restructured its R&D operation that year, cutting 10,000 jobs worldwide, closing its R&D facility in Beckenham, Kent, and opening a Medicines Research Centre in Stevenage, Hertfordshire.[27][28][29] Also that year, Glaxo Wellcome acquired the California-based Affymax, a leader in the field of combinatorial chemistry.[30]

By 1999, Glaxo Wellcome had become the world's third-largest pharmaceutical company by revenues (behind Novartis and Merck), with a global market share of around 4 per cent.[31] Its products included Imigran (for the treatment of migraine), salbutamol (Ventolin) (for the treatment of asthma), Zovirax (for the treatment of coldsores), and Retrovir and Epivir (for the treatment of AIDS). In 1999, the company was the world's largest manufacturer of drugs for the treatment of asthma and HIV/AIDS.[32] It employed 59,000 people, including 13,400 in the UK, had 76 operating companies and 50 manufacturing facilities worldwide, and seven of its products were among the world's top 50 best-selling pharmaceuticals. The company had R&D facilities in Hertfordshire, Kent, London and Verona (Italy), and manufacturing plants in Scotland and the north of England. It had R&D centres in the US and Japan, and production facilities in the US, Europe and the Far East.[33]

SmithKline Beecham

[edit]Beecham

[edit]

In 1848, Thomas Beecham launched his Beecham's Pills laxative in England, giving birth to the Beecham Group. In 1859, Beecham opened its first factory in St Helens, Lancashire. By the 1960s, Beecham was extensively involved in pharmaceuticals and consumer products such as Macleans toothpaste, Lucozade and synthetic penicillin research.[13][34]

SmithKline

[edit]John K. Smith opened his first pharmacy in Philadelphia in 1830. In 1865, Mahlon Kline joined the business, which 10 years later became Smith, Kline & Co. In 1891, it merged with French, Richard and Company, and in 1929, changed its name to Smith Kline & French Laboratories as it focused more on research. Years later it bought Norden Laboratories, a business doing research into animal health, and Recherche et Industrie Thérapeutiques in Belgium in 1963, to focus on vaccines. The company began to expand globally, buying seven laboratories in Canada and the United States in 1969. In 1982, it bought Allergan, a manufacturer of eye and skincare products.[13]

Smith Kline & French merged with Beckman Inc. in 1982, and changed its name to SmithKline Beckman.[35] In 1988, it bought International Clinical Laboratories.[36]

Merger

[edit]In 1989, SmithKline Beckman merged with Beecham Group to form SmithKline Beecham P.L.C..[37] The headquarters moved from the United States to England. To expand R&D in the United States, the company bought a new research center in 1995; another opened in 1997, in England at New Frontiers Science Park, Harlow.[13]

2000: Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham merger

[edit]Glaxo Wellcome and SmithKline Beecham announced their intention to merge in January 2000. The merger was completed on 27 December that year, forming GlaxoSmithKline (GSK).[38][39] The company's global headquarters were at GSK House, Brentford, London, officially opened in 2002, by then-Prime Minister Tony Blair. The building was erected at a cost of £300 million and as of 2002[update] was home to 3,000 administrative staff.[40]

2001–2010

[edit]

GSK completed the acquisition of New Jersey–based Block Drug in 2001, for US$1.24 billion.[41] In 2006, GSK acquired the US-based consumer healthcare company CNS Inc., whose products included Breathe Right nasal strips and FiberChoice dietary supplements, for US$566 million in cash.[42]

Chris Gent, previously CEO of Vodafone, was appointed chairman of the board in 2005.[43] GSK opened its first R&D centre in China in 2007, in Shanghai, initially focused on neurodegenerative diseases.[44] Andrew Witty became the chief executive officer in 2008.[45] Witty joined Glaxo in 1985, and had been president of GSK's Pharmaceuticals Europe since 2003.[46]

In 2009, GSK acquired Stiefel Laboratories, then the world's largest independent dermatology drug company, for US$3.6 billion.[47] In November 2009, the FDA approved GSK's vaccine for 2009 H1N1 influenza protection, manufactured by the company's ID Biomedical Corp in Canada.[48] Also in November 2009, GSK formed a joint venture with Pfizer to create ViiV Healthcare, which specializes in HIV research.[49] In 2010, the company acquired Laboratorios Phoenix, an Argentine pharmaceutical company, for US$253m,[50] and the UK-based sports nutrition company Maxinutrition for £162 million (US$256 million).[51]

2011–2022

[edit]In 2011, in a US$660-million deal, Prestige Brands Holdings took over 17 GSK brands with sales of US$210 million, including BC Powder, Beano, Ecotrin, Fiber Choice, Goody's Powder, Sominex and Tagamet.[52] In 2012, the company announced that it would invest £500 million in manufacturing facilities in Ulverston, northern England, designating it as the site for a previously announced biotech plant.[53] In May that year it acquired CellZome, a German biotech company, for US$98 million,[54] and in June, worldwide rights to alitretinoin (Toctino), an eczema drug, for US$302 million.[55] In 2013, GSK acquired Human Genome Sciences (HGS) for US$3 billion; the companies had collaborated on developing the lupus drug Belimumab (Benlysta), albiglutide for type 2 diabetes, and darapladib for atherosclerosis,[56] and in September, sold its beverage division to Suntory. This included the brands Lucozade and Ribena; however, the deal did not include Horlicks.[57]

In March 2014, GSK paid US$1 billion to raise its stake in its Indian pharmaceutical unit, GlaxoSmithKline Pharmaceuticals, to 75 per cent as part of a move to focus on emerging markets.[58] In April 2014, Novartis and Glaxo agreed on more than US$20 billion in deals, with Novartis selling its vaccine business to GSK and buying GSK's cancer business.[59][60] In February 2015, GSK announced that it would acquire GlycoVaxyn, a Swiss pharmaceutical company, for US$190 million,[61] and in June that year that it would sell two meningitis drugs to Pfizer, Nimenrix and Mencevax for around US$130 million.[62]

Philip Hampton, at that time chair of the Royal Bank of Scotland, became GSK chairman in September 2015.[63]

On 31 March 2017, Emma Walmsley became CEO. She is the first female CEO of the company.[64][65]

In December 2017, Reuters reported that Glaxo had increased its stake in its Saudi Arabian unit to 75% (from 49%) taking over control from its Saudi partner Banaja KSA Holding Company.[66]

With respect to rare diseases, the company divested its portfolio of gene therapy drugs to Orchard Therapeutics in April 2018.[67] In November 2018, Reuters reported that Unilever was in prime position to acquire GSK's interest in its Indian unit, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare Ltd, in a sale that could generate around US$4 billion for the company.[68] Nestlé and Coca-Cola have also been reported to be interested in the business unit as they look to strengthen their presence in India.[68][69] On 3 December 2018, GSK announced that Unilever would acquire the Indian-listed GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare business for US$3.8 billion (£2.98 billion). Unilever will pay the majority of the deal in cash, with the remaining being paid in shares in its Indian operation, Hindustan Unilever Limited. Upon completion, GSK will then own around 5.7% of Hindustan Unilever Limited, selling those shares in a number of tranches.[70] The same day, the company also announced it would acquire oncology specialist, Tesaro, for US$5.1 billion. The deal will give GSK control of ovarian cancer treatment, Zejula - a member of the class of poly ADP ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.[71]

In October 2019, GSK agreed to sell its rabies vaccine, RabAvert, and its tick-borne encephalitis vaccine, Encepur, to Bavarian Nordic for US$1.06 billion (€955 million).[72][73]

In July 2020, GSK acquired a 10% stake in German biotech company CureVac.[74]

GSK–Novartis consumer healthcare buy-out

[edit]In March 2018, GSK announced that it has reached an agreement with Novartis to acquire Novartis's 36.5% stake in their Consumer Healthcare Joint Venture for US$13 billion (£9.2 billion).[75][67]

GSK–Pfizer joint venture

[edit]In December 2018, GSK announced that it, along with Pfizer, had reached an agreement to merge and combine their consumer healthcare divisions into a single entity. The combined entity would have sales of around £9.8 billion ($12.7 billion), with GSK maintaining a 68% controlling stake in the joint venture. Pfizer would own the remaining 32% shareholding. The deal builds on an earlier 2018 deal where GSK bought out Novartis' stake in the GSK-Novartis consumer healthcare joint business.[76]

Subsequent split

[edit]

The culmination of the Consumer Healthcare string of deals will result in GSK splitting into two separate companies, via a demerger and subsequent listing of the joint venture. This will create two publicly traded companies, one focusing on pharmaceuticals and research & development, the other on consumer healthcare. On 22 February 2022, GSK announced that the spin-off consumer healthcare company will be called Haleon.[76][77]

In January 2022, the company announced that they had received three unsolicited offers from Unilever to acquire the Consumer Healthcare business unit, with the final proposal valuing the business unit at £50 billion (£41.7 billion in cash, plus £8.3 billion in Unilever shares).[78]

Subsequently, GSK declined all outside offers/attempts to acquire its consumer healthcare business and moved forward with its plan to complete the demerger from the main biopharmaceutical business.[79]

Recent developments

[edit]In April 2022, the business announced it would acquire Sierra Oncology Inc for $1.9 billion ($55 per share).[80] In May 2022, GSK announced it would acquire Affinivax and its phase II 24-valent pneumococcal vaccine candidate for up to $3.3 billion, strengthening its vaccine business.[81]

On 16 May 2022, the company changed its name from GlaxoSmithKline to GSK.[82]

In April 2023, GSK announced it would acquire Bellus Health Inc. for $2 billion.[83]

In February 2024, the company acquired Aiolos Bio for over $1 billion, adding to its existing asthma business through AIO-001 a long-acting monoclonal antibody that targets the thymic stromal lymphopoietin cytokine.[84][85]

In May 2024, GSK sold off its 4.2% shares in Haleon for $1.58 billion.[86][87][88]

In July 2024, GSK moved its headquarters from Brentford to New Oxford Street in central London.[89]

Acquisition-history diagram

[edit]- GSK

- GlaxoSmithKline

- SmithKline Beecham Plc (Renamed 1989)

- SmithKline Beckman (Renamed 1982)

- SmithKline-RIT (Renamed 1968)

- Smith, Kline & French (Reorganized 1929 into Smith Kline and French Laboratories)

- French, Richards and Company (Acquired 1891)

- Smith, Kline and Company

- Recherche et Industrie Thérapeutiques (Acquired 1968)

- Smith, Kline & French (Reorganized 1929 into Smith Kline and French Laboratories)

- Beckman Instruments, Inc. (Merged 1982, Sold 1989)

- Specialized Instruments Corp. (Acquired 1954)

- Offner Electronics (Acquired 1961)

- International Clinical Laboratories (Acquired 1989)

- Reckitt & Colman (Acquired 1999)

- SmithKline-RIT (Renamed 1968)

- Beecham Group Plc (Merged 1989)

- Beecham Group Ltd

- S. E. Massengill Company (Acquired 1971)

- C.L. Bencard (Acquired 1953)

- County Chemicals

- Norcliff Thayer (Acquired 1986)

- Beecham Group Ltd

- SmithKline Beckman (Renamed 1982)

- Glaxo Wellcome

- Glaxo (Merged 1995)

- Joseph Nathan & Co

- Allen & Hanburys (Founded 1715, acquired 1958)

- Meyer Laboratories (Merged 1978)

- Affymax (Acquired 1995)

- Wellcome Foundation (Renamed 1924, merged 1995)

- Burroughs Wellcome & Company (Founded 1880)

- McDougall & Robertson Inc (Acquired 1959)

- Glaxo (Merged 1995)

- SmithKline Beecham Plc (Renamed 1989)

- Block Drug (Acquired 2001)

- CNS Inc. (Acquired 2006)

- Stiefel Laboratories (Acquired 2009)

- Laboratorios Phoenix (Acquired 2010)

- Maxinutrition (Acquired 2010)

- CellZome (Acquired 2011)

- Human Genome Sciences (Acquired 2013)

- GlycoVaxyn (Acquired 2015)

- Tesaro (Acquired 2019)

- Sitari Pharmaceuticals (Acquired 2019)

- Sierra Oncology (Acquired 2022)

- Affinivax (Acquired 2022)

- Bellus Health Inc. (Acquired 2023)

- Aiolos Bio (Acquired 2024)

- GlaxoSmithKline

Research areas and products

[edit]Pharmaceuticals

[edit]GSK manufactures products for major disease areas such as asthma, cancer, infections, diabetes, and mental health. Medicines historically discovered or developed at GSK and its legacy companies and now sold as generics include amoxicillin[90] and amoxicillin-clavulanate,[91] ticarcillin-clavulanate,[92] mupirocin,[93] and ceftazidime[94] for bacterial infections, zidovudine for HIV infection, valacyclovir for herpes virus infections, albendazole for parasitic infections, sumatriptan for migraine, lamotrigine for epilepsy, bupropion and paroxetine for major depressive disorder, cimetidine and ranitidine for gastroesophageal reflux disorder, mercaptopurine[95] and thioguanine[96] for the treatment of leukemia, allopurinol for gout,[97] pyrimethamine for malaria,[98] and the antibacterial trimethoprim.[96]

Among these, albendazole, amoxicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, allopurinol, mercaptopurine, mupirocin, pyrimethamine, ranitidine, thioguanine, trimethoprim, and zidovudine are on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8]

Malaria vaccine

[edit]In 2014, GSK applied for regulatory approval for the first malaria vaccine.[7] Malaria is responsible for over 650,000 deaths annually, mainly in Africa.[99] Known as RTS,S, the vaccine was developed as a joint project with the PATH vaccines initiative and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The company has committed to making the vaccine available in developing countries for five per cent above the cost of production.[7]

As of 2013[update], RTS,S, which uses GSK's proprietary AS01 adjuvant, was being examined in a Phase 3 trial in eight African countries. PATH reported that "[i]n the 12-month period following vaccination, RTS,S conferred approximately 50% protection from clinical Plasmodium falciparum disease in children aged 5-17 months, and approximately 30% protection in children aged 6-12 weeks when administered in conjunction with Expanded Program for Immunization (EPI) vaccines."[100] In 2014, Glaxo said it had spent more than US$350 million and expected to spend an additional US$260 million before seeking regulatory approval.[101][102]

Consumer healthcare

[edit]GSK's consumer healthcare division, which earned £5.2 billion in 2013, sells oral healthcare, including Aquafresh, Macleans and Sensodyne toothpastes. GSK also previously owned the Lucozade and Ribena brands of soft drinks, but they were sold in 2013, to Suntory for £1.35bn.[57] Other products include Abreva to treat cold sores; Night Nurse, a cold remedy; Breathe Right nasal strips; and Nicoderm and Nicorette nicotine replacements.[103] In March 2014, it recalled Alli, an over-the-counter weight-loss drug, in the United States and Puerto Rico because of possible tampering, following customer complaints.[104] On 18 July 2022, GSK formally spun off its consumer healthcare business as a separate entity, Haleon.[105][106][107]

Facilities

[edit]As of 2013[update], GSK had offices in over 115 countries and employed over 99,000 people, 12,500 in R&D. The company's single largest market is the United States. Its US headquarters are in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Durham, North Carolina; its consumer-products division is in Moon Township, Pennsylvania.[108]

COVID-19 vaccine

[edit]In July 2020, the UK government signed up for 60 million doses of a COVID-19 vaccine developed by GSK and Sanofi. It uses a recombinant protein–based technology from Sanofi and GSK's pandemic technology. The companies claimed to be able to produce one billion doses, subject to successful trials and regulatory approval, during the first half of 2021.[109] The company also agreed to a $2.1 billion deal with the United States to produce 100 million doses of the vaccine.[110]

Venture arms

[edit]SR One was established in 1985, by SmithKline Beecham to invest in new biotechnology companies and continued operating after GSK was formed; by 2003, GSK had formed another subsidiary, GSK Ventures, to out-license or start new companies around drug candidates that it did not intend to develop further.[111] As of 2003[update], SR One tended to invest only if the company aligned with GSK's business.[111]

In September 2019, Avalon Ventures announced that it entered into a definitive agreement with GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) for the acquisition of Sitari Pharmaceuticals by GSK. This includes its transglutaminase 2 (TG2) small molecule program for the treatment of celiac disease.[112]

Recognition, philanthropy and social responsibility

[edit]Scientific recognition

[edit]Four GlaxoSmithKline scientists have been recognized by the Nobel Committee for their contributions to basic medical science and/or therapeutics development.

- Henry Dale, a former student of Paul Ehrlich, received the 1936 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his work on the chemical transmission of neural impulses. Dale served as a pharmacologist and then as Director of the Wellcome Physiological Research Laboratories from 1904 to 1914, and later served as Trustee and chairman of the board of the Wellcome Trust.[113]

- John Vane of Wellcome Research Laboratories shared the 1982 Nobel Prize for Medicine for his work on prostaglandin biology and the discovery of prostacyclin. Vane served as group research and development director for The Wellcome Foundation from 1973 to 1985.[114]

- Gertrude B. Elion and George Hitchings, both of the Wellcome Research Laboratories, shared the 1988 Nobel Prize in Medicine with Sir James W. Black, formerly of Smith Kline & French and the Wellcome Foundation, ""for their discoveries of important principles for drug treatment"." Elion and Hitchings were responsible for the discovery of a plethora of important drugs, including mercaptopurine[95] and thioguanine[96] for the treatment of leukemia, the immunosuppressant azothioprine,[115] allopurinol for gout,[97] pyrimethamine for malaria,[98] the antibacterial trimethoprim,[96] acyclovir for herpes virus infection,[116] and nelarabine for cancer treatment.[117]

Philanthropy and social responsibility

[edit]Since 2010, GlaxoSmithKline has several times ranked first among pharmaceutical companies on the Global Access to Medicines Index, which is funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.[118] In 2014, the Human Rights Campaign, an LGBT-rights advocacy group gave GSK a score of 100 per cent in its Corporate Equality Index.[119]

GSK has been active, with the World Health Organization (WHO), in the Global Alliance to Eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis (GAELF). Around 120 million people globally are believed to be infected with lymphatic filariasis.[120] In 2012, the company endorsed the London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases; it agreed to donate 400 million albendazole tablets to the WHO each year to fight soil-transmitted helminthiasis and to provide 600 million albendazole tablets every year for lymphatic filariasis until the disease is eradicated.[121] As of 2014[update], over 5 billion treatments had been delivered, and 18 of 73 countries in which the disease is considered endemic had progressed to the surveillance stage.[122]

In 2009, the company said it would cut drug prices by 25 per cent in 50 of the poorest nations, release intellectual property rights for substances and processes relevant to neglected disease into a patent pool to encourage new drug development, and invest 20 per cent of profits from the least-developed countries in medical infrastructure for those countries.[123][124] Médecins Sans Frontières welcomed the decision, but criticized GSK for failing to include HIV patents in its patent pool and for not including middle-income countries in the initiative.[125]

In 2013, GSK licensed its HIV portfolio to the Medicines Patent Pool for use in children, and agreed to negotiate a license for dolutegravir, an integrase inhibitor then in clinical development.[126] In 2014, this license was extended to include dolutegravir and adults with HIV. The licenses include countries in which 93 per cent of adults and 99 per cent of children with HIV live.[127] Also in 2013 GSK joined AllTrials, a British campaign to ensure that all clinical trials are registered and the results reported. The company said it would make its past clinical-trial reports available and future ones within a year of the studies' end.[128]

GSK has largely had an access strategy, providing medicines at a subsidized price to lower and middle income markets including Africa under the former CEO Andrew Witty. In 2017, its new CEO, Emma Walmsley,[129] shifted away from this with GSK exiting all Sub-Saharan African markets and there being no plans to provide its newer expensive oncology and genetics pipeline to this population.[130]

Controversies

[edit]1973 Antitrust case over griseofulvin

[edit]In the 1960s, Glaxo Group Ltd. (Glaxo) and Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) each owned patents covering various aspects of the antifungal drug griseofulvin.[131]: 54, nn. 1–2 [132] They created a patent pool by cross-licensing their patents, subject to express licensing restrictions that the chemical from which the "finished" form of the drug (tablets and capsules) was made must not be resold in bulk form, and they licensed other drug companies to sell the drug in finished form and subject to similar restrictions.[131]: 54–55 [132] The effect and intent of the bulk-sale restriction was to keep the drug chemical out of the hands of small companies that might act as price-cutters, and the effect was to maintain stable, uniform prices.[133][134][135]

The United States brought an antitrust suit against the two companies—United States v. Glaxo Group Ltd.—charging them with violation of the Sherman Act and also seeking to have the patents declared invalid.[131]: 55 [132] The trial court found that the defendants had engaged in several unlawful conspiracies, but dismissed the part of the suit seeking invalidation of patents and refused to grant as relief mandatory sales of the bulk drug chemical and compulsory licensing of the patents.[131]: 56 [132] The government appealed to the Supreme Court, which reversed, in United States v. Glaxo Group Ltd., 410 U.S. 52 (1973).[132]

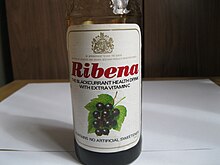

2000s Ribena

[edit]There were concerns in the 2000s about the sugar and vitamin content of Ribena, a blackcurrant-based syrup and soft drink owned by GSK until 2013. Produced in England by H.W. Carter & Co from the 1930s, the company's unbranded syrup was distributed to children as a source of vitamin C during World War II, which gave the drink a reputation as good for health. Beecham bought H. W. Carter in 1955.[136]

In 2001, the British Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) required GSK to withdraw its claim that Ribena Toothkind, a lower-sugar variety, did not encourage tooth decay. A company poster showed bottles of Toothkind in place of the bristles on a toothbrush. The ASA's ruling was upheld by the High Court.[137] In 2007, GSK was fined US$217,000 in New Zealand over its claim that ready-to-drink Ribena contained high levels of vitamin C, after two schoolgirls showed it contained no detectable vitamin C.[138] In 2013, GSK sold Ribena and another drink, Lucozade, to the Japanese multinational Suntory for £1.35 billion.[57]

SB Pharmco Puerto Rico

[edit]In 2010, the US Department of Justice announced that GSK would pay a US$150 million criminal fine and forfeiture, and a civil settlement of US$600 million under the False Claims Act. The fines stemmed from production of improperly made and adulterated drugs from 2001 to 2005, at GSK's subsidiary, SB Pharmco Puerto Rico Inc., in Cidra, Puerto Rico, which at the time produced US$5.5 billion of products each year. The drugs involved were Kytril, an antiemetic; Bactroban, used to treat skin infections; Paxil, the anti-depressant; and Avandamet, a diabetes drug.[139] GSK closed the factory in 2009.[140]

The case began in 2002, when GSK sent experts to fix problems cited by the FDA. The lead inspector recommended recalls of defective products, but they were not authorised; she was fired in 2003, and filed a whistleblower lawsuit. In 2005, federal marshals seized US$2 billion worth of products, the largest such seizure in history. In the 2010 settlement SB Pharmco pleaded guilty to criminal charges, and agreed to pay US$150 million in a criminal fine and forfeiture, at that time the largest such payment ever by a manufacturer of adulterated drugs, and US$600 million in civil penalties to settle the civil lawsuit.[140]

2010 Pandemrix connected with narcolepsy

[edit]The Pandemrix influenza vaccine was developed by GlaxoSmithKline in 2006. It was used by Finland and Sweden in the H1N1 mass vaccination of the population against the 2009 swine flu pandemic. In August 2010, The Swedish Medical Products Agency (MPA) and The Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) launched investigations regarding the development of narcolepsy as a possible side effect to Pandemrix flu vaccination in children,[141] and found a 6.6-fold increased risk among children and youths, resulting in 3.6 additional cases of narcolepsy per 100,000 vaccinated subjects.[142]

In February 2011, The Finnish National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL) concluded that there is a clear connection between the Pandemrix vaccination campaign of 2009 and 2010, and the narcolepsy epidemic in Finland. A total of 152 cases of narcolepsy were found in Finland during 2009–2010, and ninety per cent of them had received the Pandemrix vaccination.[143][144][145] Sweden however observed very few influenza cases totally in 2009 and especially 2010 as compared to most other years.[146] In 2015, it was reported that the British Department of Health was paying for Sodium oxybate medication for 80 patients who are taking legal action over problems linked to the use of the swine flu vaccine, at a cost to the government of £12,000 per patient per year.[147]

2012 criminal and civil settlement

[edit]Overview

[edit]In July 2012, GSK pleaded guilty in the United States to criminal charges, and agreed to pay US$3 billion, in what was the largest settlement until then between the Justice Department and a drug company. The US$3 billion included a criminal fine of US$956,814,400 and forfeiture of US$43,185,600. The remaining US$2 billion covered a civil settlement with the government under the False Claims Act. The investigation was launched largely on the basis of information from four whistleblowers who filed qui tam (whistleblower) lawsuits against the company under the False Claims Act.[9]

The charges stemmed from GSK's promotion of the anti-depressants Paxil (paroxetine) and Wellbutrin (bupropion) for unapproved uses from 1998 to 2003, specifically as suitable for patients under the age of 18, and from its failure to report safety data about Avandia (rosiglitazone), both in violation of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Other drugs promoted for unapproved uses were two inhalers, Advair (fluticasone/salmeterol) and Flovent (fluticasone propionate), as well as Zofran (ondansetron), Imitrex (sumatriptan), Lotronex (alosetron) and Valtrex (valaciclovir).[9]

The settlement also covered reporting false best prices and underpaying rebates owed under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, and kickbacks to physicians to prescribe GSK's drugs. There were all-expenses-paid spa treatments and hunting trips for doctors and their spouses, speakers' fees at conferences, and payment for articles ghostwritten by the company and placed by physicians in medical journals.[9] The company set up a ghostwriting programme called CASPPER, initially to produce articles about Paxil but which was extended to cover Avandia.[148]

As part of the settlement GSK signed a five-year corporate integrity agreement with the Department of Health and Human Services, which obliged the company to make major changes in the way it did business, including changing its compensation programmes for its sales force and executives, and to implement and maintain transparency in its research practices and publication policies.[9] It announced in 2013, that it would no longer pay doctors to promote its drugs or attend medical conferences, and that its sales staff would no longer have prescription targets.[149]

Rosiglitazone (Avandia)

[edit]

The 2012 settlement included a criminal fine of US$242,612,800 for failing to report safety data to the FDA about Avandia (rosiglitazone), a diabetes drug approved in 1999, and a civil settlement of US$657 million for making false claims about it. The Justice Department said GSK had promoted rosiglitazone to physicians with misleading information, including that it conferred cardiovascular benefits despite an FDA-mandated label warning of cardiovascular risks.[9]

In 1999, John Buse, a diabetes specialist, told medical conferences that rosiglitazone might carry an increased risk of cardiovascular problems. GSK threatened to sue him, called his university head of department, and persuaded him to sign a retraction.[150] GSK raised questions internally about the drug's safety in 2000, and in 2002, the company ghostwrote an article in Circulation describing a GSK funded clinical trial that suggested rosiglitazone might have a beneficial effect on cardiovascular risk.[151] From 2001, reports began to link the thiazolidinediones (the class of drugs to which rosiglitazone belongs) to heart failure.[152] In April that year, GSK began a six-year, open-label, randomized trial, known as RECORD, to examine rosiglitazone and cardiovascular events.[153] Two GSK meta-analyses in 2005, and 2006, showed an increased risk of cardiovascular problems with rosiglitazone; the information was passed to the FDA and posted on the company website, but not otherwise published. By December 2006, rosiglitazone had become the top-selling diabetes drug, with annual sales of US$3.3 billion.[152]

In June 2007, The New England Journal of Medicine published a meta-analysis that associated the drug with an increased risk of heart attack.[154] GSK had reportedly tried to persuade one of the authors, Steven Nissen, not to publish it, after receiving an advance copy from one of the journal's peer reviewers, a GSK consultant.[155][156] In July 2007, FDA scientists suggested that rosiglitazone had caused 83,000 excess heart attacks between 1999 and 2007.[157]: 4 [158] The FDA placed restrictions on the drug, including adding a boxed warning, but did not withdraw it.[159] (In 2013, the FDA rejected that the drug had caused excess heart attacks.)[160] A Senate Finance Committee inquiry concluded in 2010, that GSK had sought to intimidate scientists who had concerns about rosiglitazone.[157] In February that year the company tried to halt publication of an editorial about the controversy by Nissen in the European Heart Journal.[161]

The results of GSK's RECORD trial were published in June 2009. It confirmed an association between rosiglitazone and an increased risk of heart failure and fractures, but not of heart attack, and concluded that it "does not increase the risk of overall cardiovascular morbidity or mortality compared with standard glucose-lowering drugs."[153] Steven Nissan and Kathy Wolkski argued that the study's low event rates reduced its statistical power.[162] In September 2009, rosiglitazone was suspended in Europe.[163] The results of the RECORD study were confirmed in 2013, by the Duke Clinical Research Institute, in an independent review required by the FDA.[164] In November that year the FDA lifted the restrictions it had placed on the drug.[165] The boxed warning about heart attack was removed; the warning about heart failure remained in place.[160]

Paroxetine (Paxil/Seroxat)

[edit]

GSK was fined for promoting Paxil/Seroxat (paroxetine) for treating depression in the under-18s, although the drug had not been approved for pediatric use.[9] Paxil had US$4.97 billion worldwide sales in 2003.[166] The company conducted nine clinical trials between 1994, and 2002, none of which showed that Paxil helped children with depression.[167] From 1998, to 2003, it promoted the drug for the under-18s, paying physicians to go on all-expenses paid trips, five-star hotels and spas.[9] From 2004, Paxil's label, along with those of similar drugs, included an FDA-mandated boxed warning that it might increase the risk of suicidal ideation and behaviour in patients under 18.[9]

An internal SmithKline Beecham document said in 1998, about withheld data from two GSK studies: "It would be commercially unacceptable to include a statement that [pediatric] efficacy had not been demonstrated, as this would undermine the profile of paroxetine."[166][168] The company ghostwrote an article, published in 2001, in the Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, that misreported the results of one of its clinical trials, Study 329.[9][169] The article concluded that Paxil was "generally well tolerated and effective for major depression in adolescents."[170] The suppression of the research findings is the subject of the 2008 book Side Effects by Alison Bass.[171][172]

For 10 years GSK marketed Paxil as non-habit forming. In 2001, 35 patients filed a class-action suit alleging they had had withdrawal symptoms, and in 2002, a Los Angeles court issued an injunction preventing GSK from advertising that the drug was not habit forming.[173] The court withdrew the injunction after the FDA objected that the court had no jurisdiction over drug marketing that the FDA had approved.[174] In 2003, a World Health Organization committee reported that Paxil was among the top 30 drugs, and top three antidepressants, for which dependence had been reported.[175][n 2]

Bupropion (Wellbutrin)

[edit]The company was also fined for promoting Wellbutrin (bupropion) – approved at the time for major depressive disorder and also sold as a smoking-cessation aid, Zyban – for weight loss and the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, sexual dysfunction and substance addiction. GSK paid doctors to promote these off-label uses, and set up supposedly independent advisory boards and Continuing Medical Education programmes.[9]

Bribery in China

[edit]In 2013, Chinese authorities announced that, since 2007, GSK had funnelled HK$3.8 billion in kickbacks to GSK managers, doctors, hospitals and others who prescribed their drugs, using over 700 travel agencies and consulting firms.[176] Chinese authorities arrested four GSK executives as part of a four-month investigation into claims that doctors were bribed with cash and sexual favours.[177] In 2014, a Chinese court found the company guilty of bribery and imposed a fine of US$490 million. Mark Reilly, the British head of GSK's Chinese operations, received a three-year suspended prison sentence after a one-day trial held in secret.[178] Reilly was reportedly deported from China and dismissed by the company.[179]

Market manipulation in the UK

[edit]In February 2016, the company was fined over £37 million in the UK by the Competition and Markets Authority for paying Generics UK, Alpharma and Norton Healthcare more than £50m between 2001, and 2004, to keep generic varieties of paroxetine out of the UK market. The generics companies were fined a further £8 million. At the end of 2003, when generics became available in the UK, the price of paroxetine dropped by 70 per cent.[180]

Miscellaneous

[edit]Italian police sought bribery charges in May 2004, against 4,400 doctors and 273 GSK employees. GSK and its predecessor were accused of having spent £152m on physicians, pharmacists and others, giving them cameras, computers, holidays and cash. Doctors were alleged to have received cash based on the number of patients they treated with a cancer drug, topotecan (Hycamtin).[181] The following month prosecutors in Munich accused 70–100 doctors of having accepted bribes from SmithKline Beecham between 1997 and 1999. The inquiry was opened over allegations that the company had given over 4,000 hospital doctors money and free trips.[182][183] All charges were dismissed by the Verona court in January 2009.[184]

In 2006, in the United States GSK settled the largest tax dispute in IRS history, agreeing to pay US$3.1 billion. At issue were Zantac and other products sold in 1989 to 2005. The case revolved around intracompany transfer pricing—determining the share of profit attributable to the US subsidiaries of GSK and subject to tax by the IRS.[185][186]

The UK's Serious Fraud Office (SFO) opened a criminal inquiry in 2014 into GSK's sales practices, using powers granted by the Bribery Act 2010.[187] The SFO said it was collaborating with Chinese authorities to investigate bringing charges in the UK related to GSK's activities in China, Europe and the Middle East.[188] Also as of 2014[update], the US Department of Justice was investigating GSK with reference to the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act.[189]

In October 2020, GSK told some staff that while at work they should disable the contact tracing function of the NHS test-and-trace app which monitors the spread of COVID-19. GSK explained the reason for this was due to social distancing measures in place at their sites rendering the technology unnecessary.[190]

In November 2023, GSK filed a lawsuit against Moderna Inc. in U.S. federal court in Delaware, accusing the company of violating GSK's patents related to messenger RNA (mRNA) technology. The lawsuit claims that Moderna's COVID-19 vaccine Spikevax and RSV vaccine mResvia infringe on several of GSK's patents, particularly those related to lipid nanoparticles used for delivering mRNA into the human body.[191] This legal action follows a similar lawsuit GSK filed against Pfizer and BioNTech earlier in 2024, also over patent infringement concerning their mRNA-based COVID-19 vaccine. The current litigation seeks unspecified monetary damages from Moderna.[191]

Operation in Russia

[edit]Following Russia's invasion of Ukraine in 2022, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) was criticized for continuing its operations in Russia, despite the ongoing conflict and international sanctions. Although GSK suspended clinical trials, advertising, and promotion in Russia, the company has maintained its supply of essential medicines, vaccines, and medical equipment, with proceeds reportedly directed towards humanitarian aid. Critics argue that GSK's decision to continue exporting products—resulting in increased sales and profit volumes in 2022 compared to 2021—undermines the intended impact of sanctions, raising ethical concerns.[192][193][194]

See also

[edit]- List of toothpaste brands

- Galvani Bioelectronics

- Index of oral health and dental articles

- Recherche et Industrie Thérapeutiques (R.I.T.)

51°29′17″N 0°19′1″W / 51.48806°N 0.31694°W

Notes

[edit]- ^ Glaxo Wellcome was formed from Glaxo's 1995 acquisition of The Wellcome Foundation and SmithKline Beecham from the 1989 merger of the Beecham Group and the SmithKline Beckman Corporation.

- ^ World Health Organization Expert Committee on Drug Dependence, 2003: "The Committee noted the striking number of reports on paroxetine and 'withdrawal syndrome' ... The representative of Consumers International reported that a number of patients had experienced difficulty in withdrawing from SSRIs in general. It was agreed that withdrawal was indeed a problem in some patients, but there was a difference of opinion on the degree of dependence that was involved, given the possibility that the need for treatment of resistant or relapsing disease could make these drugs indispensable for patient care. The Committee expressed concern about the possibility of inappropriate prescribing resulting in the risk of problems of withdrawal outweighing the benefits of treatment with SSRIs."[175]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Preliminary Results 2023" (PDF). GSK. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "At a glance". GSK. Retrieved 11 February 2024.

- ^ "Headquarters | GSK US". us.gsk.com. Archived from the original on 22 May 2022. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "GlaxoSmithKline on the Forbes Top Multinational Performers List". Forbes. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ "Global 500". Fortune. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ "FTSE All-Share Index Ranking". stockchallenge.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 March 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Plumridge H (24 July 2014). "Glaxo Files Its Entry in Race for a Malaria Vaccine". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

Lorenzetti L (24 July 2014). "GlaxoSmithKline seeks approval on first-ever malaria vaccine". Fortune. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ^ a b World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "GlaxoSmithKline to Plead Guilty and Pay $3 Billion to Resolve Fraud Allegations and Failure to Report Safety Data" Archived 9 September 2014 at the Wayback Machine, United States Department of Justice, 2 July 2012.

Katie Thomas and Michael S. Schmidt, "Glaxo Agrees to Pay $3 Billion in Fraud Settlement" Archived 2 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The New York Times, 2 July 2012.

Simon Neville, "GlaxoSmithKline fined $3bn after bribing doctors to increase drugs sales", The Guardian, 3 July 2012.

- ^ R. P. T. Davenport-Hines, Judy Slinn, Glaxo: A History to 1962, Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 7–13.

- ^ David Newton, Trademarked: A History of Well-Known Brands, from Airtex to Wright's Coal Tar, The History Press, 2012, p. 435.

- ^ a b c d Ravenscraft DJ, Long WF (January 2000). "Paths to Creating Value in Pharmaceutical Mergers" (PDF). National Bureau of Economic Research. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "GSK History". GlaxoSmithKline. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 18 April 2011.

- ^ New "Glaxo" Company. The Times, Tuesday, 15 October 1935; pg. 22; Issue 47195

- ^ J. Nathan And "Glaxo" Reorganization. The Times, Wednesday, 8 January 1947; pg. 8; Issue 50653

- ^ Joseph Nathan & Co. The Times, Thursday, 20 February 1947; pg. 8; Issue 50690

- ^ a b Kumar BR (2012). Mega Mergers and Acquisitions: Case Studies from Key Industries. Cham: Springer. p. 14. ISBN 978-1-137-00590-8.

- ^ "Eastchester: History of the Town" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2016.

- ^ "Addition to Factory" Archived 1 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Eastchester Citizen-Bulletin, 19 November 1924

- ^ Peter Pennoyer, Anne Walker, The Architecture of Delano & Aldrich, W. W. Norton & Company, 2003, p. 188.

- ^ "Iconic Burroughs Wellcome Headquarters Open for Rare Public Tour" Archived 28 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Triangle Modernist Houses, press release, 8 October 2012.

- ^ Cummings AS (13 June 2016). "Into the Spaceship: A Visit to the Old Burroughs Wellcome Building". Tropics of Meta historiography for the masses. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 25 November 2019.

- ^ Bouton K (29 January 1989). "The Nobel Pair". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Kaji-O'Grady S, Smith CL (2019). LabOratory: Speaking of Science and Its Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-262-35636-7.

- ^ a b Stradling R (21 September 2020). "United Therapeutics to demolish an RTP landmark building". News & Observer. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021.

- ^ Lesney MS (January 2004). "The ghosts of pharma past" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 January 2023.

- ^ Grimond M (15 June 1995). "10,000 face Glaxo's axe at Wellcome". The Independent. Archived from the original on 6 July 2022.

- ^ Grimond M (21 June 1995). "Glaxo warns of redundancies". The Independent. Archived from the original on 26 February 2014.

- ^ Grimond M (7 September 1995). "Glaxo Wellcome plans to axe 7,500 jobs". The Independent. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022.

- ^ "Glaxo to Acquire Affymax". The New York Times. 27 January 1995. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "Outlook: Glaxo Wellcome". The Independent. 30 March 1999. Archived from the original on 16 March 2023.

- ^ "Company of the week: Glaxo Wellcome". The Independent. 1 August 1999. Archived from the original on 24 November 2022.

- ^ "Profile: Glaxo Wellcome". BBC News. 17 January 2000. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023.

- ^ Corely T (2011). Beechams, 1848-2000: from Pills to Pharmaceuticals. Crucible Books. ISBN 978-1905472147.

- ^ Kleinfield NR (29 May 1984). "Smithkline: One-Drug Image". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "SmithKline Beckman Corp. and International Clinical Laboratories Inc. announced..." UPI. 13 April 1988. Archived from the original on 30 September 2019. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ Lohr S (13 April 1989). "SmithKline, Beecham to Merge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 22 May 2023. Retrieved 30 September 2019.

- ^ "The new alchemy – The drug industry's flurry of mergers is based on a big gamble". The Economist. 20 January 2000. Archived from the original on 25 July 2023.

- ^ Gershon D (May 2000). "Partners resolve their differences and unite at the second attempt". Nature. 405 (6783): 258. doi:10.1038/35012210. PMID 10821289. S2CID 23140509.

- ^ "Hall that glitters isn't shareholder gold". The Daily Telegraph. 15 July 2002. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ "GlaxoSmithKline Completes the Purchase of Block Drug for $1.24 Billion". PR Newswire. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ Stouffer R (9 October 2006). "Glaxo unit buys Breathe Right maker". Trib Live. Archived from the original on 28 July 2013.

- ^ "Sir Christopher Gent to exit GlaxoSmithKline". The Telegraph. 28 October 2012. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ Ben Hirschler (24 May 2007). "Glaxo China R&D centre to target neurodegeneration". Reuters. Archived from the original on 11 August 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

Cyranoski D (29 October 2008). "Pharmaceutical futures: Made in China?". Nature. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 13 July 2012. - ^ "Corporate Executive Team", GlaxoSmithKline. Retrieved 16 November 2013. Archived 14 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Andrew Witty's journey from Graduate to GSK CEO" Archived 9 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, GlaxoSmithKline, 12 August 2008; "Andrew Philip Witty", Bloomberg.

- ^ Ruddick G (20 April 2009). "GlaxoSmithKline buys Stiefel for $3.6bn". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022.

- ^ "FDA Approves Additional Vaccine for 2009 H1N1 Influenza Virus". US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 16 November 2009. Archived from the original on 19 November 2009.

- ^ Jack A (16 April 2009). "Companies / Pharmaceuticals – GSK and Pfizer to merge HIV portfolios". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022.

- ^ "GSK Acquires Laboratorios Phoenix for 3m | InfoGrok". infogrok.com. 14 June 2010. Archived from the original on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ Sandle P (13 December 2010). "UPDATE 2-Glaxo buys protein-drinks firm Maxinutrition". Reuters. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010.

- ^ Ranii D (21 December 2011). "GSK sells BC, Goody's and other brands". News & Observer. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012.

- ^ "GSK confirms 500 mln stg UK investment plans". Reuters. 22 March 2012. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ European Biotechnology News 16 May 2012. GSK acquires Cellzome 100%: Britain's largest drugmaker GlaxoSmithKline will pay about €75m in cash to acquire Cellzome AG completely Archived 4 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine; John Carroll for FierceBiotech 15 May 2012 GSK snags proteomics platform tech in $98M Cellzome buyout

- ^ John Carroll for FiercePharma. 12 June 2012 GSK continues deal spree with $302M pact for Basilea eczema drug Archived 29 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine; Basilea Pharmaceutica Press Release. 11 June 2012 Basilea enters into global agreement with Stiefel, a GSK company, for Toctino (alitretinoin)

- ^ Herper M (16 July 2012). "Three Lessons From GlaxoSmithKline's Purchase Of Human Genome Sciences". Forbes. Archived from the original on 27 May 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Monaghan A (9 September 2013). "Ribena and Lucozade sold to Japanese drinks giant". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ Hirschler B (10 March 2014). "GSK pays $1 billion to lift Indian unit stake to 75 percent". Reuters. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Bray C, Jolly D (23 April 2014). "Novartis and Glaxo Agree to Trade $20 Billion in Assets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Rockoff JD, Whalen J, Falconi M (22 April 2014). "Deal Flurry Shows Drug Makers' Swing Toward Specialization". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 10 September 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ "GEN - News Highlights:GSK Acquires GlycoVaxyn for $190M". GEN. 11 February 2015. Archived from the original on 3 April 2023.

- ^ "Pfizer Buys Two GSK Meningitis Vaccines for $130M". GEN. 22 June 2015. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Quinn J (25 September 2014). "Sir Philip Hampton to chair Glaxo". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ Herper M. "GlaxoSmithKline Appoints Big Pharma's First Woman Chief Executive". Forbes. Archived from the original on 10 September 2023. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ^ Yeomans J (20 September 2016). "Emma Walmsley becomes latest female CEO in FTSE 100 as she replaces Sir Andrew Witty at GSK". The Telegraph. Daily Telegraph, London. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ "GlaxoSmithKline boosts stake in Saudi Arabia unit". Reuters. 18 December 2017. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023.

- ^ a b "GlaxoSmithKline considers splitting up the group - FT". Reuters. 21 July 2018. Archived from the original on 21 July 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ a b Gruber KW (28 November 2018). "Unilever in pole position to swallow GSK's Indian Horlicks business". Reuters. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ Sagonowsky E (28 November 2018). "GlaxoSmithKline taps Unilever as lead bidder in Indian Horlicks buyout: report". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 28 November 2018.

- ^ "Unilever swallows GSK's Indian Horlicks business for $3.8 billion". Reuters. 3 December 2018. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Hirschler B (3 December 2018). "GSK slides after buying cancer firm Tesaro for hefty $5.1 billion". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2018.

- ^ Sagonowsky E (21 October 2019). "Zeroing in on fast-growing vaccines, GSK sheds 2 shots to Bavarian Nordic for up to $1.1B". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on 5 January 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ "GSK agrees to divest rabies and tick-borne encephalitis vaccines to Bavarian Nordic". GSK. 21 October 2019. Archived from the original on 4 August 2023. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ^ Schuetze A, Aripaka P (20 July 2020). "GSK buys 10% of CureVac in vaccine tech deal". Reuters. Archived from the original on 20 July 2020 – via uk.reuters.com.

- ^ Shields M (27 March 2018). "GSK buys out Novartis in $13 billion consumer healthcare shake-up". Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 March 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ a b Hirschler B (19 December 2018). "Drugmaker GSK to split after striking Pfizer consumer health deal". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2018.

- ^ Freeman S (22 February 2022). "Hello, Haleon: GlaxoSmithKline reveals name of £60bn consumer health spin-out". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 23 February 2022.

- ^ Cavale S, Burger L, Dey M (15 January 2022). "GSK rejects 50-billion-pound Unilever offer for consumer assets". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 January 2022 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "Pfizer to exit GSK consumer health joint venture after London listing". Financial Times. 1 June 2022. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- ^ Grover N, Shabong Y (13 April 2022). "GSK to buy Sierra Oncology amid pressure to boost drug pipeline". Reuters. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ Keown A (31 May 2022). "GSK Bolsters Vaccines Business with $3.3B Affinivax Buy". Biospace. Archived from the original on 5 February 2023. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ "Change of name". London Stock Exchange. 16 May 2022. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2022.

- ^ Susin M (18 April 2023). "GSK: To Acquire The Late-stage Biopharmaceutical Group For $14.75 Per Share". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 18 April 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2023.

- ^ "GSK Puts $1.4B on the Line in Aiolos Acquisition to Boost Asthma Pipeline".

- ^ "GSK completes acquisition of Aiolos Bio for up to $1.4 bln". Reuters. 16 February 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2024.

- ^ "GSK sells off remaining stake in Haleon". www.ft.com. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "GSK to sell remaining 4.2% stake in Haleon". Sharecast. Retrieved 17 May 2024.

- ^ "GSK Sells Last Haleon Shares for $1.58 Bln". Marketwatch.

- ^ "GSK moves to new HQ in return to central London". The Independent. 13 July 2024. Retrieved 16 July 2024.

- ^ "Most-recognized brands: Anti-infectives, December 2013". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 27 January 2023.

- ^ Geddes AM, Klugman KP, Rolinson GN (December 2007). "Introduction: historical perspective and development of amoxicillin/clavulanate". Int J Antimicrob Agents. 30 (Suppl 2): S109–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.015. PMID 17900874.

- ^ Brown AG (August 1986). "Clavulanic acid, a novel beta-lactamase inhibitor--a case study in drug discovery and development". Drug Des Deliv. 1 (1): 1–21. PMID 3334541.

- ^ "mupirocin search results". DailyMed. Archived from the original on 4 December 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Richards DM, Brogden RN (February 1985). "Ceftazidime. A review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use". Drugs. 29 (2): 105–61. doi:10.2165/00003495-198529020-00002. PMID 3884319. S2CID 265707490.

- ^ a b "Chemical & Engineering News: Top Pharmaceuticals: 6-Mercaptopurine". pubsapp.acs.org. Archived from the original on 1 June 2023. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d "George Hitchings and Gertrude Elion". Science History Institute. June 2016. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b Elion GB (1989). "The purine path to chemotherapy". Science. 244 (4900): 41–7. Bibcode:1989Sci...244...41E. doi:10.1126/science.2649979. PMID 2649979.

- ^ a b Altman LK (23 February 1999). "Gertrude Elion, Drug Developer, Dies at 81". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 17 October 2009.

- ^ "Press release: Malaria vaccine candidate reduces disease over 18 months of follow-up in late-stage study of more than 15,000 infants and young children". PATH. Archived from the original on 15 April 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ Birkett AJ, Moorthy VS, Loucq C, et al. (April 2013). "Malaria vaccine R&D in the Decade of Vaccines: breakthroughs, challenges and opportunities". Vaccine. 31 (Supplement 2): B233–43. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.02.040. PMID 23598488.

- ^ "Malaria vaccine candidate reduces disease over 18 months of follow-up in late-stage study of more than 15,000 infants and young children". GlaxoSmithKline. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- ^ McNeil DG Jr (18 October 2011). "Scientists See Promise in Vaccine for Malaria". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023.

- ^ Majumdar R (2007). Product management in India (3rd ed.). PHI Learning. p. 242. ISBN 978-81-203-3383-3.

- ^ Smith A (27 March 2014). "Alli, a popular weight-loss drug, is recalled by maker GlaxoSmithKline for possible tampering". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ Kansteiner F (17 May 2024). "GSK offloads remaining stake in Haleon for £1.25B". www.fiercepharma.com.

- ^ "Consumer Healthcare Demerger | GSK". www.gsk.com.

- ^ Roland D. "GSK Spins Off $36 Billion Consumer-Healthcare Business Haleon". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "About us: what we do", GlaxoSmithKline, accessed 16 November 2013 Archived 13 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Coronavirus vaccine: UK signs deal with GSK and Sanofi". BBC News. 29 July 2020. Archived from the original on 29 July 2020.

- ^ Lovelace Jr B (31 July 2020). "U.S. agrees to pay Sanofi and GSK $2.1 billion for 100 million doses of coronavirus vaccine". CNBC. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020.

- ^ a b Reaume A (1 January 2003). "Is Corporate Venture Capital a Prescription for Success in the Pharmaceutical Industry?". The Journal of Private Equity. 6 (4): 77–87. doi:10.3905/jpe.2003.320058. JSTOR 43503355. S2CID 154182967.

- ^ Keown A (11 September 2019). "GSK to Acquire Celiac-Focused Sitari Pharmaceuticals". BioSpace. Archived from the original on 22 September 2019.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1936". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 26 August 2018.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1982". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 20 February 2019.

- ^ Maltzman JS, Koretzky GA (April 2003). "Azathioprine: old drug, new actions". J. Clin. Invest. 111 (8): 1122–4. doi:10.1172/JCI18384. PMC 152947. PMID 12697731.

- ^ Elion GB (1993). "Acyclovir: discovery, mechanism of action, and selectivity". J. Med. Virol. Suppl 1: 2–6. doi:10.1002/jmv.1890410503. PMID 8245887. S2CID 37848199.

- ^ Koenig R (2006). "The legacy of great science: the work of Nobel Laureate Gertrude Elion lives on". Oncologist. 11 (9): 961–5. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.11-9-961. PMID 17030634.

- ^ "Access to medicine" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2014.

- ^ Human Rights Campaign. Profile: Buyers Guide entry for GlaxoSmithKline Archived 13 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed 16 May 2014

- ^ "Global alliance to eliminate Lymphatic Filariasis". Ifpma.org. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008.

- ^ "Private and Public Partners Unite to Combat 10 Neglected Tropical Diseases by 2020". Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. 30 January 2012. Archived from the original on 14 March 2013. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

"Research-based pharma pledges on neglected tropical diseases". The Pharma Letter. 31 January 2012. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2013.

- ^ "Global programme to eliminate lymphatic filariasis: progress report, 2014" (PDF). World Health Organization. 18 September 2015. p. 490. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2015.

- ^ Boseley S (13 February 2009). "Drug giant GlaxoSmithKline pledges cheap medicine for world's poor". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ UNITAID 16 February 2009. UNITAID Statement on GSK Patent Pool For Neglected Diseases Archived 27 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Guardian: Letter in response to GSK's patent pool proposal". Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign. 24 February 2009. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ "GlaxoSmithKline unit joins patent pool for AIDS drugs". Reuters. 27 February 2013. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023.

- ^ "Medicines Patent Pool, ViiV Healthcare Sign Licence for the Most Recent HIV Medicine to Have Received Regulatory Approval". Medicines Patent Pool. 1 April 2014. Archived from the original on 2 June 2023.

- ^ Ben Goldacre, Bad Pharma, Fourth Estate, 2013 [2012], p. 387.

- ^ Palmer E (17 January 2018). "GSK cutting jobs in sub-Saharan Africa, will rely on distributors". Fierce Pharma. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Mwangi K (15 October 2022). "GSK stops Nairobi production as high costs and low sales eat into revenue". The East African. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 9 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d "UNITED STATES v. GLAXO GROUP LTD., 410 U.S. 52 (1973)". FindLaw. Archived from the original on 11 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e LaHatte G (2011). "Reverse Payments: When the Federal Trade Commission can Attack the Validity of Underlying Patents". Case Western Reserve Journal of Law, Technology & the Internet. 2: 37–73. Archived from the original on 18 November 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- ^ Leslie CR (2011). Antitrust Law and Intellectual Property Rights: Cases and Materials. Oxford University Press. pp. 574–75. ISBN 9780195337198.

- ^ United States v. Glaxo Group Ltd. Archived 4 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine at 62-63.

- ^ Jacobson JM (2007). Antitrust Law Developments. American Bar Association. p. 1162. ISBN 9781590318676.

- ^ Oliver Thring, "Consider squash and cordial" Archived 10 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, 7 September 2010.

"We have Frank and Vernon to thank for Ribena" Archived 18 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Bristol Post, 17 September 2013.

- ^ Gregoriadis L (18 January 2001). "Makers of Ribena lose fight over anti-decay claims". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ Eames D (28 March 2007). "Judge orders Ribena to fess up". The New Zealand Herald. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 15 April 2018.

Tony Jaques, "When an Icon Stumbles – The Ribena Issue Mismanaged" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 13(4), 2008, pp. 394–406.

Michael Regester, Judy Larkin, Risk Issues and Crisis Management in Public Relations, Kogan Page Publishers, 2008, p. 67ff.

- ^ "Office of Public Affairs | GlaxoSmithKline to Plead Guilty & Pay $750 Million to Resolve Criminal and Civil Liability Regarding Manufacturing Deficiencies at Puerto Rico Plant | United States Department of Justice". www.justice.gov. 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ a b Harris G, Wilson D (26 October 2010). "Glaxo to Pay $750 Million for Sale of Bad Products". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023.

- ^ "The MPA investigates reports of narcolepsy in patients vaccinated with Pandemrix". The Swedish Medical Products Agency. 18 August 2010. Archived from the original on 17 February 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ Report from an epidemiological study in Sweden on vaccination with Pandemrix and narcolepsy Archived 15 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Swedish medical product agency, 30 June 2011.

- ^ "THL: Pandemrixilla ja narkolepsialla on selvä yhteys". Mtv3.fi. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos - THL". Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "Narkolepsia ja sikainfluenssarokote - THL". Terveyden ja hyvinvoinnin laitos. Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ^ "Statistikdatabas för dödsorsaker (den öppna delen av dödsorsaksregistret)" (in Swedish). Socialstyrelsen. Archived from the original on 13 February 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2020., diagnoskod J09, J10 och J11

- ^ Lintern S (20 July 2015). "DH funds private prescriptions for drug denied to NHS patients". Health Service Journal. Archived from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Max Baucus, Chuck Grassley, "Finance Committee Letter to the FDA Regarding Avandia" Archived 5 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, United States Senate Finance Committee, 12 July 2010.

Jim Edwards, "Inside GSK's CASSPER Ghostwriting Program", CBS News, 21 August 2009. - ^ "GSK to stop paying doctors in major marketing overhaul" Archived 28 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Thomson/Reuters, 17 December 2013.

- ^ "United States Senate Committee on Finance Report: The Intimidation of Dr. John Buse and the Diabetes Drug Avandia". www.finance.senate.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ Max Baucus, Chuck Grassley, "Finance Committee Letter to the FDA Regarding Avandia" Archived 5 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, United States Senate Finance Committee, 12 July 2010; for internal concerns, p. 2 and attachment E, pp. 20–35; for ghostwriting, p. 3 and attachment H, pp. 58–109; for the ghostwriting, attachment I, p. 110ff; for cover letter to Circulation, attachment I, p. 143; for the ghostwritten article, attachment I, pp. 152–158.

Haffner SM, Greenberg AS, Weston WM, et al. (August 2002). "Effect of rosiglitazone treatment on nontraditional markers of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus". Circulation. 106 (6): 679–84. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000025403.20953.23. PMID 12163427.

- ^ a b Nissen SE (April 2010). "The rise and fall of rosiglitazone". European Heart Journal. 31 (7): 773–776. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq016. PMID 20154334. see table 1 for timeline.

- ^ a b Home PD, Pocock SJ, Beck-Nielsen H, et al. (June 2009). "Rosiglitazone evaluated for cardiovascular outcomes in oral agent combination therapy for type 2 diabetes (RECORD): a multicentre, randomised, open-label trial". Lancet. 373 (9681): 2125–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60953-3. PMID 19501900. S2CID 25939495.

Home PD, Pocock SJ, Beck-Nielsen H, et al. (September 2005). "Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiac Outcomes and Regulation of Glycaemia in Diabetes (RECORD): study design and protocol". Diabetologia. 48 (9): 1726–35. doi:10.1007/s00125-005-1869-1. PMID 16025252.

"RECORD: Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiac Outcomes and Regulation of Glycaemia in Diabetes - Full Text View". ClinicalTrials.gov. 21 March 2017. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Nissen SE, Wolski K (2007). "Effect of Rosiglitazone on the Risk of Myocardial Infarction and Death from Cardiovascular Causes". New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (24): 2457–71. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072761. PMID 17517853.

Rosiglitazone was associated with a significant increase in the risk of myocardial infarction and with an increase in the risk of death from cardiovascular causes that had borderline significance.

- ^ Saul S (30 January 2008). "Doctor Accused of Leak to Drug Maker". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ Harris G (22 February 2010). "A Face-Off on the Safety of a Drug for Diabetes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Staff report on GlaxoSmithKline and the diabetes drug Avandia" Archived 6 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Committee on Finance, United States Senate, January 2010.

"Grassley, Baucus Release Committee Report on Avandia" Archived 6 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, The United States Senate Committee on Finance, 20 February 2010.

Andrew Clark, "Glaxo's handling of Avandia concerns damned by US Senate committee", The Guardian, 22 February 2010.

- ^ David Graham, "Assessment of the cardiovascular risks and health benefits of rosiglitazone" Archived 17 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Office of Surveillance and Epidemiology, Food and Drug Administration, 30 July 2007.

- ^ "FDA Adds Boxed Warning for Heart-related Risks to Anti-Diabetes Drug Avandia". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 14 November 2007. Archived from the original on 18 June 2009.

- ^ a b "FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA requires removal of some prescribing and dispensing restrictions for rosiglitazone-containing diabetes medicines". Food and Drug Administration. 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 24 April 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

Avandia. Prescribing information" Archived 27 March 2019 at the Wayback Machine, Food and Drug Administration. - ^ Thomas F. Lüscher, Ulf Landmesser, Frank Ruschitzka (23 April 2010). "Standing firm—the European Heart Journal, scientific controversies and the industry". European Heart Journal. 31 (10): 1157–1158. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq127.

Nissen SE (April 2010). "The rise and fall of rosiglitazone". Eur. Heart J. 31 (7): 773–6. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq016. PMID 20154334.

Slaoui M (2010). "The rise and fall of rosiglitazone: reply". Eur. Heart J. 31 (10): 1282–4. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehq118. PMID 20499440.

Komajda M, McMurray JJ, Beck-Nielsen H, Gomis R, Hanefeld M, Pocock SJ, Curtis PS, Jones NP, Home PD (2010). "Heart failure events with rosiglitazone in type 2 diabetes: data from the RECORD clinical trial". Eur. Heart J. 31 (7): 824–31. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp604. PMC 2848325. PMID 20118174.

- ^ Nissen SE, Wolski K (July 2010). "Rosiglitazone RevisitedAn Updated Meta-analysis of Risk for Myocardial Infarction and Cardiovascular Mortality". Archives of Internal Medicine. 170 (14): 1191–1202. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.207. PMID 20656674.

That study was limited by low event rates, which resulted in insufficient statistical power to confirm or refute evidence of an increased risk for ischemic myocardial events.

- ^ "European Medicines Agency recommends suspension of Avandia, Avandamet and Avaglim". European Medicines Agency. 17 September 2018. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 11 September 2023.

- ^ McHaffey KW, et al. (2013). "Results of a reevaluation of cardiovascular outcomes in the RECORD trial". American Heart Journal. 166 (2): 240–249. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.05.004. PMID 23895806.

- ^ "FDA requires removal of certain restrictions on the diabetes drug Avandia" Archived 4 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Food and Drug Administration, 25 November 2013.

"Readjudication of the Rosiglitazone Evaluated for Cardiovascular Outcomes and Regulation of Glycemia in Diabetes Trial (RECORD)" Archived 9 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Joint Meeting of the Endocrinologic and Metabolic Drugs Advisory Committee and the Drug Safety and Risk Management Advisory Committee, Food and Drug Administration, 5–6 June 2013.

Steven Nissen, "Steven Nissen: The Hidden Agenda Behind The FDA's New Avandia Hearings" Archived 8 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Forbes, 23 May 2013.

"The FDA Responds To Steve Nissen's Criticism Of Upcoming Avandia Meeting", Forbes, 23 May 2013.

- ^ a b W. Kondro, B. Sibbald (March 2004). "Drug company experts advised staff to withhold data about SSRI use in children". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 170 (5): 783. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1040213. PMC 343848. PMID 14993169.

- ^ Goldacre 2013, p. 58.

- ^ Samson K (December 2008). "Senate probe seeks industry payment data on individual academic researchers". Annals of Neurology. 64 (6): A7–9. doi:10.1002/ana.21271. PMID 19107985. S2CID 12019559.

- ^ Letter showing authorship of Study 239 Archived 5 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Drug Industry Document Archive, University of California, San Francisco.

Isabel Heck, "Controversial Paxil paper still under fire 13 years later" Archived 5 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Brown Daily Herald, 2 April 2014.