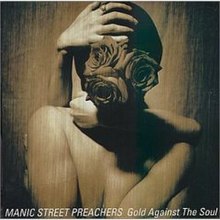

Gold Against the Soul

| Gold Against the Soul | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 21 June 1993 | |||

| Recorded | January–March 1993 | |||

| Studio | Outside Studios, Checkendon, England | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 42:51 | |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Producer | Dave Eringa | |||

| Manic Street Preachers chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Gold Against the Soul | ||||

| ||||

Gold Against the Soul is the second studio album by Welsh alternative rock band Manic Street Preachers, released on 21 June 1993 by Columbia Records. The follow-up to the band's 1992 debut album Generation Terrorists, the record reached No.8 on the UK Albums Chart.

Gold Against the Soul takes to an extreme the hard rock sound of its predecessor and saw the band experiment with styles including funk and the then-contemporary grunge.[1][2][3] The album's lyrical themes owed little to the political and social commentaries of its predecessor, and instead explored more personal themes of depression, melancholy and nostalgia.[4]

Recording

[edit]The band stated that the choice to work with Dave Eringa again was important for this album: "We finished work in November and then just went straight into a demo studio and we came out about four weeks later with the album all finished. We were all happy with all the songs, we knew what they wanted to sound like, so we didn't want to use a mainstream producer because they've got their own sound and vision of what a record should be like. So we just phoned Dave up and said 'Look, come down, let's see how this works out', and everyone loved what we were doing, so we decided to stay with him."[4]

When asked to look back on the album, the band themselves have described Gold Against the Soul as their least favourite album and the period surrounding the album as being the most unfocused of their career. The band's vocalist and guitarist James Dean Bradfield has said "All we wanted to do was go under the corporate wing. We thought we could ignore it but you do get affected."[5]

Content

[edit]Lyrics, writing and themes

[edit]Simon Price of The Telegraph opined that the lyrics on Gold Against the Soul "switched from the political [of Generation Terrorists] to the personal".[6] The lyrical content is considerably less political than their previous album Generation Terrorists, and the album is more reflective of the despair and melancholy of their later work.[4]

"La Tristesse Durera" (literally "the sadness will go on") is the title of a biography of Vincent van Gogh, although the song is not about him but about a war veteran.[7]

Style and influences

[edit]The album presents a different sound from their debut album, not only in terms of lyrics but in sound. The band privileged long guitar riffs and the drums feel more present and loud in the final mix of the album. This sound would be abandoned in their next album.[4] According to AllMusic, the album takes "the hard rock inclinations of Generation Terrorists to an extreme."[1] Meanwhile, Dave de Sylvia at Sputnikmusic characterized it as a glam rock album, similar to that of Bon Jovi,[7] with Simon Price likening the record to "a blend of Bon Jovi and Nirvana".[6] Cam Lindsay of Exclaim! proclaimed it to be a "sullen glam rock" album.[8] Writing Leyendas Urbanas del Rock in 2019, José Luis Martín proclaimed that Gold Against the Soul saw the Manics "abandon glam punk and dangerously approach grunge".[9] Tom Doyle of Q called the sound of the album "epic pop-rock",[10] while Gigwise described it as "hair metal".[11]

The album displayed a variety of styles; "Roses in the Hospital" tapped into a "stadium funk-rock" style,[12] while "From Despair to Where" incorporated a quiet-loud dynamic; "follow[ing] the grunge template" in the words of Rob Jovanocic.[3]

Regarding the album's influences, bassist Nicky Wire remarked that Gold Against the Soul was "all Alice in Chains and Red Hot Chili Peppers", and that he was emulating Flea at the time.[13]

Release

[edit]Gold Against the Soul was released on 14 June 1993. It reached number 8 on the UK Albums Chart. The album has since gone Gold (100,000 copies) and spent more than 10 weeks in the Top 75.[14] Gold Against the Soul also charted within the Top 100 in Germany and within the Top 50 in Japan.

Four singles were released from the album. "From Despair to Where" was the lead single. "La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh)" was the second single from the album and it has been described by many as its highlight. The third single, "Roses in the Hospital", peaked at number 15 on the UK Singles Chart, the highest-charting single from the band's first three albums.[14] The fourth and final single, "Life Becoming a Landslide", charted at number 36, which would be the lowest charting single by the band until 2011's "Some Kind of Nothingness".[14]

In March 2020, following several anniversary re-releases of old albums in previous years, the Manics announced a deluxe reissue of Gold Against the Soul for release on 12 June 2020. Bonus content included previously unreleased demos, B-sides from the era, remixes, and a live recording, while the CD was released alongside a book of unseen photographs from the era with handwritten annotations and lyrics from the band.[15]

Reception

[edit]| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Mojo | |

| Music Week | |

| NME | 6/10[18] |

| PopMatters | 7/10[19] |

| Q | |

| Record Collector | |

| Select | 4/5[22] |

| Uncut | 8/10[23] |

| Under the Radar | 9/10[24] |

| Vox | 6/10[25] |

Gold Against the Soul has received generally mixed reviews from critics.

Stuart Bailie, writing for the NME, called the album "confusing" and "too much Slash and not enough burn", but did compliment its musicality, saying "the drums and guitars rumble higher in the mix, and massive, harmonising riffs are everywhere".[18] In his review for Vox, Keith Cameron remarked that the album showed Manic Street Preachers "skating gingerly over that treacherous Difficult Second Album ice".[25] Q's Peter Kane was more critical, calling the album "superficially competent, of course, but scratch below the surface and you'll find few signs of life, just a vaguely expressed, bemused and bored dissatisfaction".[20] In Spin, Simon Reynolds opined that the band "motor-mouth a fine manifesto, but haven't got a musical bone between them".[26]

Among more favourable reviews, Stuart Maconie of Select praised the album as "a mammoth development even from their excellent debut" and "almost without exception terrific",[22] while Melody Maker remarked that the band had "stayed beautiful".[27] Kerrang! and Melody Maker listed Gold Against the Soul at number 8[28] and number 25, respectively,[29] in their end-of-year lists of the best albums of 1993.

Legacy

[edit]Both the NME and Q have since revised their opinions of Gold Against the Soul in some later articles, with the former's Paul Stokes opining that its short, "snappy, driven and focused" length contrasts with other albums' "indulgently lengthy tracklistings", and suggesting that "with its big, radio-friendly Dave Eringa production, it's easy to see why Gold Against the Soul caused such a stir compared to the wild, almost feral rock of Generation Terrorists that preceded it a year earlier. However, with the band's more beefed up, arena-friendly sound emerging in subsequent years, this album is no longer so at odds with the general Manics aesthetic."[30] The latter publication, in a retrospective review of The Holy Bible, looked back on Gold Against the Soul as "an underrated pop-metal effort that's armed with a handful of bona-fide big tunes", and cited "La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh)" as its highlight.[31]

In his retrospective review, Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic described Gold Against the Soul as a "flawed but intriguing second album".[1] Sputnikmusic writer Dave de Sylvia called it "a fine, and certainly underappreciated, album which fell victim to the weight of expectation generated by its predecessor and fell well short of the standard set by its successor, The Holy Bible, released the following year. The album has many flaws – it's rushed; it's formulaic in parts; the music was sometimes compromised in the search for a hit, but behind these flaws lies a solid rock 'n' roll album with a deeper, more profound edge than most any other rock album you'll hear."[7] Joe Tangari of Pitchfork, however, lambasted Gold Against the Soul as a "labored, sophomore-slumping hard rock turd that had them looking washed up early", concluding that "there was really no preparation for the intensity, perversion and genuine darkness of The Holy Bible" which would follow in 1994.[32]

"It's fair to say that history judged Gold… slightly unjustly," wrote Drowned in Sound's Ben Patashnik in 2008. He added that the album was "heavy, melodic and packed full of huge choruses: radio-friendly doesn’t have to be used in the pejorative sense and it's certainly more considered and mature than their debut."[33] Tom Ewing of Freaky Trigger hailed Gold Against the Soul as "a half-classic of sensitive metal" that built upon the style of the Manics' earlier single "Motorcycle Emptiness". He highlighted the "confused-nihilist persona internalised and fucked up to the point of collapse, while the riffs just keep on playing."[34] In 2013, "La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh)" was chosen by Clash as one of their favourite Manic Street Preachers singles.[35]

Gold Against the Soul was given a deluxe re-issue in 2020 with each track remastered, complete with a 120-page A4 book of photos taken by Mitch Ikeda and scans of original lyric sheets plus previously unreleased demos. In his review for FMS Magazine, Jimi Arundell addresses the discomfort the band have previously expressed about the record; "It seems that the band have exorcised the needless shame they have always seemed to carry for their second album, and finally given Gold Against The Soul the respect it deserves".[36]

Track listing

[edit]All lyrics are written by Richey Edwards and Nicky Wire, except where noted; all music is composed by James Dean Bradfield and Sean Moore, except where noted

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Sleepflower" | 4:51 |

| 2. | "From Despair to Where" | 3:34 |

| 3. | "La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh)" (titled "Scream to a Sigh (La Tristesse Durera)" on US releases) | 4:13 |

| 4. | "Yourself" | 4:11 |

| 5. | "Life Becoming a Landslide" | 4:14 |

| 6. | "Drug Drug Druggy" | 3:26 |

| 7. | "Roses in the Hospital" | 5:02 |

| 8. | "Nostalgic Pushead" | 4:14 |

| 9. | "Symphony of Tourette" | 3:31 |

| 10. | "Gold Against the Soul" | 5:34 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Slash 'n' Burn" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | 3:27 |

| 2. | "Crucifix Kiss" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | 4:46 |

| 3. | "Motown Junk" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | 3:05 |

| 4. | "Tennessee" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | 3:00 |

| 5. | "You Love Us" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | 3:00 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Roses in the Hospital" (O.G. Psychovocal mix) | 4:50 |

| 2. | "Roses in the Hospital" (51 Funk Salute mix) | 5:45 |

| 3. | "Roses in the Hospital" (ECG mix) | 4:42 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Hibernation" | |

| 2. | "Patrick Bateman" | |

| 3. | "Us Against You" | |

| 4. | "Are Mothers Saints" | |

| 5. | "Charles Windsor" (McCarthy cover) | |

| 6. | "Slash 'n' Burn" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | |

| 7. | "Crucifix Kiss" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | |

| 8. | "Motown Junk" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | |

| 9. | "Tennessee" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | |

| 10. | "You Love Us" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) | |

| 11. | "R.P. McMurphy" (live at Club Citta, Kawasaki, May 13, 1993) |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. | "Donkeys" | ||

| 12. | "Comfort Comes" | ||

| 13. | "Are Mothers Saints" | ||

| 14. | "Patrick Bateman" | ||

| 15. | "Hibernation" | ||

| 16. | "Us Against You" | ||

| 17. | "Charles Windsor" (McCarthy cover) | Malcolm Eden, Tim Gane, John Williamson, Gary Baker | |

| 18. | "Wrote for Luck" (Happy Mondays cover) | Shaun Ryder, Paul Ryder, Mark Day, Paul Davis, Gary Whelan, Mark "Bez" Berry | |

| 19. | "What's My Name" (live Clash cover) | Joe Strummer, Mick Jones, Keith Levene |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Sleepflower" (House in the Woods demo) | |

| 2. | "From Despair to Where" (House in the Woods demo) | |

| 3. | "La Tristesse Durera (Scream To a Sigh)" (House in the Woods demo) | |

| 4. | "Yourself" (live in Bangkok) | |

| 5. | "Life Becoming a Landslide" (House in the Woods demo) | |

| 6. | "Drug Drug Druggy" (House in the Woods demo) | |

| 7. | "Drug Drug Druggy" (Impact demo) | |

| 8. | "Roses in the Hospital" (House in the Woods demo) | |

| 9. | "Roses in the Hospital" (Impact demo) | |

| 10. | "Nostalgic Pushead" (House in the Woods demo) | |

| 11. | "Symphony Of Tourette" (House in the Woods demo) | |

| 12. | "Gold Against The Soul" (House in the Woods demo) | |

| 13. | "Roses in the Hospital" (OG Psychovocal remix) | |

| 14. | "Roses in the Hospital" (51 Funk Salute) | |

| 15. | "La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh)" (Chemical Brothers vocal remix) | |

| 16. | "Roses in the Hospital" (Filet O Gang remix) | |

| 17. | "Roses in the Hospital" (ECG remix) |

Personnel

[edit]Manic Street Preachers

- James Dean Bradfield – lead vocals, lead, rhythm and acoustic guitars, backing vocals

- Richey Edwards (credited as Richey James) – rhythm guitar (credited but only performs on 'La Tristesse Durera (Scream to a Sigh)'), backing vocals

- Sean Moore – drums, sampled percussion, drum programming on "Nostalgic Pushead" and "Gold Against the Soul", additional programming, backing vocals

- Nicky Wire – bass guitar, backing vocals

|

Additional musicians

|

Technical personnel

|

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1993) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[37] | 95 |

| Japanese Albums (Oricon)[38] | 32 |

| UK Albums (OCC)[39] | 8 |

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Gold Against the Soul – Manic Street Preachers". AllMusic. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ Clarke, Allison (25 April 2016). "Manic Street Preachers: Anything but Everything Must Go". LouderSound. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- ^ a b Jovanovic, Rob (2010). A Version of Reason: The Search for Richey Edwards. Hachette UK. ISBN 9781409111290.

- ^ a b c d Price (1999).

- ^ "James Dean Bradfield of the Manic Street Preachers on a year of hospital horror..." Select. Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- ^ a b Price, Simon (24 October 2004). "Manic Street Preachers: Sublime and ridiculous". The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ a b c de Sylvia, Dave (20 August 2005). "Manic Street Preachers – Gold Against the Soul". Sputnikmusic. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- ^ Lindsay, Cam (24 May 2016). "An Essential Guide to Manic Street Preachers". Exclaim!. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Martin, Jose Luis (29 July 2019). Leyendas Urbanas del Rock (in Spanish). Ma Non Troppo. ISBN 978-84-9917-574-4. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Doyle, Tom (June 1996). "Manic Street Preachers: Everything Must Go". Q. EMAP. p. 116. Archived from the original on 21 April 2001. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Trefor, Cai (25 November 2015). "The 27 greatest Welsh bands of all time". Gigwise. Retrieved 14 May 2021.

- ^ Scott, Ben P (11 June 2020). "ALBUM REVIEW: Manic Street Preachers – Gold Against The Soul (Deluxe Reissue)". XSNoise. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ Trendell, Andrew (11 March 2020). "Nicky Wire tells us about the Manics' 'Gold Against The Soul' reissue: "It's a strange and curious record"". NME. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ a b c "Manic Street Preachers". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on 15 June 2011. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- ^ "Gold Against the Soul Deluxe Re-Issue". Manic Street Preachers. 11 March 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2020.

- ^ Gilbert, Pat (August 2020). "Manic Street Preachers: Gold Against the Soul – Deluxe Edition". Mojo. No. 321. p. 102.

- ^ Jones, Alan (26 June 1993). "Market Preview: Mainstream - Albums — Pick of the Week" (PDF). Music Week. p. 11. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ a b Bailie, Stuart (19 June 1993). "Manic Street Preachers: Gold Against the Soul". NME. p. 31.

- ^ Carr, Paul (12 June 2020). "Manic Street Preachers Remaster 'Gold Against the Soul' with Deluxe Edition". PopMatters. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b Kane, Peter (August 1993). "Manic Street Preachers: Gold Against the Soul". Q. No. 83. p. 89. Archived from the original on 11 March 2002. Retrieved 4 January 2013.

- ^ "Manic Street Preachers: Gold Against the Soul". Record Collector. No. 507. July 2020.

- ^ a b Maconie, Stuart (August 1993). "Dai harder!". Select. No. 38. p. 99.

- ^ Sharp, Johnny (August 2020). "Manic Street Preachers: Gold Against the Soul". Uncut. No. 279. p. 50.

- ^ Gourlay, Dom (22 June 2020). "Manic Street Preachers: Gold Against the Soul – Deluxe Edition (Columbia/Sony)". Under the Radar. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ a b Cameron, Keith (August 1993). "Manic Depression". Vox. No. 35. p. 73.

- ^ Reynolds, Simon (October 1993). Marks, Craig (ed.). "Manic Street Preachers: Gold Against the Soul". Spin. Vol. 9, no. 7. p. 104. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "Manic Street Preachers: Gold Against the Soul". Melody Maker. 26 June 1993. p. 28.

- ^ "Rocklist.net...Kerrang! Lists Page 1..." Rocklist.net. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ "Albums of the Year". Melody Maker. 1 January 1994. p. 77.

- ^ Stokes, Paul (12 May 2011). "Album A&E – Manic Street Preachers, 'Gold Against The Soul'". NME. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ Grundy, Gareth (December 2004). "They took a trip to the heart of darkness. Not all returned". Q. No. 221. Archived from the original on 7 December 2004. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ Tangari, Joe (17 January 2005). "Manic Street Preachers: The Holy Bible". Pitchfork. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ Patashnik, Ben (25 February 2008). "Discography reassessed: the Manics in perspective". Drowned in Sound. Archived from the original on 4 February 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Ewing, Tom (26 November 1999). "19. Manic Street Preachers – "Motorcycle Emptiness"". Freaky Trigger. Retrieved 2 June 2019.

- ^ Murray, Robin; James, Gareth; Diver, Mike (23 August 2013). "7 of the Best: Manic Street Preachers". Clash. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ Arundell, Jimi (11 June 2020). "Manic Street Preachers Reissue Gold Against The Soul & Finally Give Their Second Album the Respect It Deserves". FMS. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – Manic Street Preachers – Gold Against the Soul" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

- ^ "マニック・ストリート・プリーチャーズのアルバム売り上げランキング" (in Japanese). Oricon. Archived from the original on 3 June 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "Official Albums Chart Top 100". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 3 July 2020.

External links

[edit]- Gold Against the Soul at YouTube (streamed copy where licensed)

- Gold Against the Soul at Discogs (list of releases)