Slavery in the colonial history of the United States

The institution of slavery in the European colonies in North America, which eventually became part of the United States of America, developed due to a combination of factors. Primarily, the labor demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were targets of enslavement by Europeans during the era.

As the Spaniards, French, Dutch, and British gradually established colonies in North America from the 16th century onward, they began to enslave indigenous people, using them as forced labor to help develop colonial economies. As indigenous peoples suffered massive population losses due to imported diseases, Europeans quickly turned to importing slaves from Africa, primarily to work on slave plantations that produced cash crops. The enslavement of indigenous people in North America was later replaced during the 18th century by the enslavement of black African people. Concurrent with the development of slavery, racist ideology was developed among Europeans, the rights of free people of color in European colonies were curtailed, slaves were legally defined as chattel property, and the condition of slavery as hereditary.

The Thirteen Colonies of northern British America, were for much or all of the period less dependent on slavery than the Caribbean colonies, or those of New Spain, or Brazil, and slavery did not develop significantly until later in the colonial era. Nonetheless, slavery was legal in every colony prior to the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), and was most prominent in the Southern Colonies (as well as, the southern Mississippi River and Florida colonies of France, Spain, and Britain), which by then developed large slave-based plantation systems. Slavery in Europe's North American colonies which did not have warm climates and ideal conditions for plantations to exist primarily took the form of domestic labor or doing other forms of unpaid work alongside non-enslaved counterparts. The American Revolution led to the first abolition laws in the Americas, although the institution of chattel slavery would continue to exist and expand across the Southern United States until finally being abolished at the time of the American Civil War in 1865.[2][3][4]

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labor and slavery |

|---|

|

Native Americans

[edit]

Native Americans enslaved members of their own and other tribes, usually as a result of taking captives in raids and warfare, both before and after Europeans arrived. This practice continued into the 1800s. In some cases, especially for young women or children, Native American families adopted captives to replace members they had lost. Among those native to the modern Southeastern United States, the children of slaves were considered free.[5][6] Slaves included captives from wars and slave raids; captives bartered from other tribes, sometimes at great distances; children sold by their parents during famines; and men and women who staked themselves in gambling when they had nothing else, which put them into servitude in some cases for life.[5]

In three expeditions between 1514 and 1525, Spanish explorers visited the Carolinas and enslaved Native Americans, who they took to their base on Santo Domingo.[7][8][9] The Spanish Crown's charter for its 1526 colony in the Carolinas and Georgia was more restrictive. It required that Native Americans be treated well, paid, and converted to Christianity, but it also allowed already enslaved Native Americans to be bought and exported to the Caribbean if they had been enslaved by other Native Americans.[9] This colony did not survive, so it is not clear if it exported any slaves. Native Americans were enslaved by the Spanish in Florida under the encomienda system.[10][11] New England and the Carolinas captured Native Americans in wars and distributed them as slaves.[12] Native Americans captured and enslaved some early European explorers and colonists.[5]

Larger societies structured as chiefdoms kept slaves as unpaid field laborers. In band societies, owning enslaved captives attested to the captor's military prowess.[13] Some war captives were subjected to ritualized torture and execution.[14] Alan Gallay and other historians emphasize differences between Native American enslavement of war captives and the European slave trading system, into which numerous native peoples were integrated.[15] Richard White, in The Middle Ground, elucidates the complex social relationships between Native American groups and the early empires, including 'slave' culture and scalping.[16] Robbie Ethridge states,

Let there be no doubt...that the commercial trade in Indian slaves was not a continuation and adaptation of pre-existing captivity patterns. It was a new kind of slave, requiring a new kind of occupational specialty ... organized militaristic slavers.[17]

One example of militaristic slaving can be seen in Nathaniel Bacon's actions in Virginia during the late 1670s. In June 1676, the Virginia assembly granted Bacon and his men what equated to a slave-hunting license by providing that any enemy Native Americans caught were to be slaves for life. They also provided soldiers who had captured Native Americans with the right to "reteyne and keepe all such Indian slaves or other Indian goods as they either have taken or hereafter shall take."[18] By this order, the assembly had made a public decision to enslave Native Americans. In the years to follow, other laws resulted in Native Americans being grouped with other non-Christian servants who had been imported to the colonies (Negro slaves) as slaves for life.

Puritan New England, Virginia, Spanish Florida, and the Carolina colonies engaged in large-scale[citation needed] enslavement of Native Americans, often through the use of Indian proxies to wage war and acquire the slaves. In New England, slave raiding accompanied the Pequot War and King Philip's War but declined after the latter war ended in 1676. Enslaved Native Americans were in Jamestown from the early years of the settlement,[citation needed] but large-scale cooperation between slave-trading English colonists and the Westo and Occaneechi peoples, whom they armed with guns, did not begin until the 1640s. These groups conducted enslaving raids in what is now Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, and possibly Alabama.[19] The Carolina slave trade, which included both trading and direct raids by colonists,[20] was the largest among the British colonies in North America,[21] estimated at 24,000 to 51,000 Native Americans by Gallay.[22]

Historian Ulrich Phillips argues that Africans were inculcated as slaves and the best answer to the labor shortage in the New World because Native American slaves were more familiar with the environment, and would often successfully escape into the frontier territory they knew. Africans had more difficulty surviving in unknown territory. Africans were also more familiar with large scale indigo and rice cultivation, of which Native Americans were unfamiliar.[23] The early colonial America depended heavily on rice and indigo cultivation[24] producing disease-carrying mosquitoes caused malaria, a disease the Africans were far less susceptible to than Native American slaves.[25]

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Native American slavery, the enslavement of Native Americans by European colonists, was common. Many of these Native slaves were exported to the Northern colonies and to off-shore colonies, especially the "sugar islands" of the Caribbean.[5][6] The exact number of Native Americans who were enslaved is unknown because vital statistics and census reports were at best infrequent.[26] Historian Alan Gallay has estimated that from 1670 to 1715, slave traders in the Province of Carolina sold between 24,000 and 51,000 Native Americans into slavery as part of the Indian slave trade in the American Southeast.[27] Andrés Reséndez estimates that between 147,000 and 340,000 Native Americans were enslaved in North America, excluding Mexico.[28] Even after the Indian Slave Trade ended in 1750 the enslavement of Native Americans continued in the west, and also in the Southern states mostly through kidnappings.[29][30]

Slavery of Native Americans was organized in colonial and Mexican California through Franciscan missions, theoretically entitled to ten years of Native labor, but in practice maintaining them in perpetual servitude, until their charge was revoked in the mid-1830s. Following the 1847–48 invasion by U.S. troops, the "loitering or orphaned Indians" were de facto enslaved in the new state from statehood in 1850 to 1867.[31] Slavery required the posting of a bond by the slave holder and enslavement occurred through raids and a four-month servitude imposed as a punishment for Indian "vagrancy".[32]

The first enslaved Africans

[edit]Carolinas

[edit]The first African slaves in what would become the present-day United States of America arrived in Puerto Rico in the early 16th century, at the hands of the Portuguese.[33] The island's native population was conquered by the Spanish settler Juan Ponce de León with the help of a free West African conquistador, Juan Garrido, by 1511. The slave population on the island grew after the Spanish crown granted import rights to its citizens, but did not reach its peak until the 18th century.[33] African slaves arrived on August 9, 1526, in Winyah Bay (off the coast of present-day South Carolina) with a Spanish expedition. Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón brought 600 colonists to start a colony at San Miguel de Gualdape. Records say the colonists included enslaved Africans, without saying how many. After a month Ayllón moved the colony to what is now Georgia.[8][9]

Until the early 18th century, enslaved Africans were difficult to acquire in the British mainland colonies. Most were sold from Africa to the West Indies for the labor-intensive sugar trade. The large plantations and high mortality rates required continued importation of slaves. One of the first major centers of African slavery in the English North American colonies occurred with the founding of Charles Town and the Province of Carolina (later, South Carolina) in 1670. The colony was founded mainly by sugar planters from Barbados, who brought relatively large numbers of African slaves from that island to develop new plantations in the Carolinas.[34]

To meet agricultural labor needs, colonists also practiced Indian slavery for some time. The Carolinians transformed the Indian slave trade during the late 17th and early 18th centuries by treating such slaves as a trade commodity to be exported, mainly to the West Indies. Historian Alan Gallay estimates that between 1670 and 1715, an estimated 24,000 to 51,000 captive Native Americans were exported from South Carolina to the Caribbean. This was a much higher number than the number of Africans imported to the English mainland colonies during the same period.[35]

In 1733, royal governor George Burrington complained that no ships brought their slave cargoes from Africa directly to the Province of North Carolina.[36]

Georgia

[edit]The first African slaves in what is now Georgia arrived in mid-September 1526 with Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón's establishment of San Miguel de Gualdape for the Spanish Crown.[8][9][37][38][39] They rebelled and lived with indigenous people, destroying the Spanish colony in less than two months.[37][40]

Two centuries later, the Province of Georgia was the last of Britain's Thirteen Colonies to be established and the farthest south. (Florida, a possession of Spain, lay just to its south). Founded in 1733, British Georgia and its powerful backers did not necessarily object to slavery as an institution, but their business model relied first on labor from Britain (primarily England's poor). The British were also concerned with security, given the closeness of Spanish Florida and Spain's regular offers to enemy-slaves to revolt or escape. Despite support for slavery, it was not until the defeat of the Spanish by Georgia's British colonials in the 1740s (Battle of Bloody Marsh) that arguments for opening the colony to slavery intensified. To staff Georgia's new rice plantations and settlements, the colony's proprietors relented in 1751, and African slavery grew quickly. After becoming a British royal colony in the 1760s, Georgia began importing slaves directly from Africa.[41]

Florida

[edit]One African slave, Estevanico arrived with the Narváez expedition in Tampa Bay in April 1528 and marched north with the expedition until September, when they embarked on rafts from the Wakulla River, heading for Mexico.[42] African slaves arrived again in Florida in 1539 with Hernando de Soto, and in the 1565 founding of St. Augustine, Florida.[39][40] When St. Augustine was founded in 1565, the site already had enslaved Native Americans, whose ancestors had migrated from Cuba.[5] The Spanish settlement was sparse and they held comparatively few slaves.[43]

The Spanish promised freedom to refugee slaves from the English colonies of South Carolina and Georgia in order to destabilize English settlement.[44][45] If the slaves converted to Catholicism and agreed to serve in a militia for Spain, they could become Spanish citizens. By 1730 the black settlement known as Fort Mose developed near St. Augustine and was later fortified. There were two known Fort Mose sites in the eighteenth century, and the men helped defend St. Augustine against the British. It is "the only known free black town in the present-day southern United States that a European colonial government-sponsored.[46] The Fort Mose Site, today a National Historic Landmark, is the location of the second Fort Mose."[46] During the nineteenth century, this site became marsh and wetlands.

In 1763, Great Britain took over Florida in an exchange with Spain after defeating France in the Seven Years' War. Spain evacuated its citizens from St. Augustine, including the residents of Fort Mose, transporting them to Cuba. As British colonists developed the colony for plantation agriculture, the percentage of slaves in the population in twenty years rose from 18% to almost 65% by 1783.[47]

Texas and the southwest

[edit]An African slave, Estevanico, reached Galveston island in November 1528, with the remnants of the Narváez expedition in Florida. The group headed south on the mainland in 1529, trying to reach Spanish settlements. They were captured and held by Native Americans until 1535.[42] They traveled northwest to the Pacific Coast, then south along the coast to San Miguel de Culiacán, which had been founded in 1531, and then to Mexico City.[42]

Spanish Texas had few African slaves, but the colonists enslaved many Native Americans.[48] Beginning in 1803, Spain freed slaves who escaped from the Louisiana territory, recently acquired by the United States.[49] More African-descended slaves were brought to Texas by American settlers.

Virginia and Chesapeake Bay

[edit]The first recorded Africans in Virginia arrived in late August 1619. The White Lion, a privateer ship owned by Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick but flying a Dutch flag, docked at what is now Old Point Comfort (located in modern-day Hampton) with approximately 20 Africans. They were captives from the area of present-day Angola and had been seized by the privateer's crew from a Portuguese slave ship, the "São João Bautista".[50][51] To obtain the Africans, the Jamestown colony traded provisions with the ship.[52] Some number of these individuals appear to have been treated like indentured servants, since slave laws were not passed until later, in 1641 in Massachusetts and in 1661 in Virginia.[53] But from the beginning, in accordance with the custom of the Atlantic slave trade, most of this relatively small group, appear to have been treated as slaves, with "African" or "negro" becoming synonymous with "slave".[54] Virginia enacted laws concerning runaway slaves and 'negroes' in 1672.[55]

Some number of the colony's early Africans earned freedom by fulfilling a work contract or for converting to Christianity.[56] At least one of these, Anthony Johnson, in turn, acquired slaves or indentured servants for workers himself. Historians such as Edmund Morgan say this evidence suggests that racial attitudes were much more flexible in early 17th-century Virginia than they would later become.[57] A 1625 census recorded 23 Africans in Virginia. In 1649 there were 300, and in 1690 there were 950.[58] Over this period, legal distinctions between white indentured servants and "Negros" widened into lifelong and inheritable chattel-slavery for Africans and people of African descent.[59]

New England

[edit]The 1677 work The Doings and Sufferings of the Christian Indians documented how hundreds of Praying Indians, who were allied with the New England Colonies, were enslaved and sent to the West Indies in the aftermath of King Philip's War by the colonists.[60][61] Captive indigenous opponents, including women and children, were also sold into slavery at a substantial profit, to be transported to West Indies colonies.[62][63]

African and Native American slaves made up a smaller part of the New England economy, which was based on yeoman farming and trades, than in the South, and a smaller fraction of the population, but they were present.[64] Most were house servants, but some worked at farm labor.[65] The Puritans codified slavery in 1641.[66][67] The Massachusetts Bay royal colony passed the Body of Liberties, which prohibited slavery in some instances, but did allow three legal bases of slavery.[67] Slaves could be held if they were captives of war, if they sold themselves into slavery, were purchased from elsewhere, or if they were sentenced to slavery by the governing authority.[67] The Body of Liberties used the word "strangers" to refer to people bought and sold as slaves, as they were generally not native born English subjects. Colonists came to equate this term with Native Americans and Africans.[68]: 261

The New Hampshire General Court passed "An Act To Prevent Disorders In The Night" in 1714, prefiguring the development of sundown towns in the United States:[69][70]

Whereas great disorders, insolencies and burglaries are oft times raised and committed in the night time by Indian, Negro, and Molatto Servants and Slaves to the Disquiet and hurt of her Majesty's subjects, No Indian, Negro, or Molatto is to be from Home after 9 o'clock.

Notices emphasizing and re-affirming the curfew were published in The New Hampshire Gazette in 1764 and 1771.[69]

New York and New Jersey

[edit]The Dutch West India Company introduced slavery in 1625 with the importation of eleven enslaved blacks who worked as farmers, fur traders, and builders to New Amsterdam (present day New York City), capital of the nascent province of New Netherland.[71] The Dutch colony expanded across the North River (Hudson River) to Bergen (in today's New Jersey). Later, slaves were also held privately by settlers in the area.[72][73] Although enslaved, the Africans had a few basic rights and families were usually kept intact. They were admitted to the Dutch Reformed Church and married by its ministers, and their children could be baptized. Slaves could testify in court, sign legal documents, and bring civil actions against whites. Some were permitted to work after hours earning wages equal to those paid to white workers. When the colony fell to the English in the 1660s, the company freed all its slaves, which created an early nucleus of free Negros in the area.[71]

The English continued to import slaves to New York. Slaves in the colony performed a wide variety of skilled and unskilled jobs, mostly in the burgeoning port city and surrounding agricultural areas. In 1703 more than 42% of New York City's households held slaves, a percentage higher than in the cities of Boston and Philadelphia, and second only to Charleston in the South.[74]

Midwest, Mississippi River, and Louisiana

[edit]

The French introduced legalized slavery into their colonies in New France both near the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River. They also used slave labor on their island colonies in the Caribbean: Guadeloupe and especially Saint-Domingue. After the port of New Orleans was founded in 1718 with access to the Gulf Coast, French colonists imported more African slaves to the Illinois Country for use as agricultural or mining laborers. By the mid-eighteenth century, slaves accounted for as much as one-third of the limited population in that rural area.[75]

Slavery was much more extensive in lower colonial Louisiana, where the French developed sugar cane plantations along the Mississippi River. Slavery was maintained during the French (1699–1763, and 1800–1803) and Spanish (1763–1800) periods of government. The first people enslaved by the French were Native Americans, but they could easily escape into the countryside which they knew well. Beginning in the early 18th century, the French imported Africans as laborers in their efforts to develop the colony. Mortality rates were high for both colonists and Africans, and new workers had to be regularly imported.

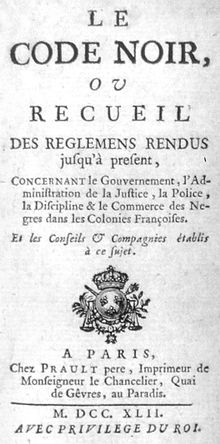

Implemented in colonial Louisiana in 1724, Louis XIV of France's Code Noir regulated the slave trade and the institution of slavery in the French colonies. As a result, Louisiana and the Mobile, Alabama areas developed very different patterns of slavery compared to the British colonies.[76]

As written, the Code Noir gave some rights to slaves, including the right to marry. Although it authorized and codified cruel corporal punishment against slaves under certain conditions, it forbade slave owners to torture slaves, to separate married couples, and to separate young children from their mothers. It required owners to instruct slaves in the Catholic faith, implying that Africans were human beings endowed with a soul, an idea that had not been acknowledged until then.[77][78][79]

The Code Noir forbade interracial marriages, but interracial relationships were formed in La Louisiane from the earliest years. In New Orleans society particularly, a formal system of concubinage, known as plaçage, developed. Usually formed between young white men and African or African-American women, these relationships were formalized with contracts that sometimes provided for freedom for a woman and her children (if she was still enslaved), education for the mixed-race children of the union, especially boys; and sometimes a property settlement. Free people of color became an intermediate social caste between whites and enslaved blacks; many practiced artisan trades, and some acquired educations and property. Some white fathers sent their mixed-race sons to France for education in military schools.

Gradually in the English colonies, slavery became known as a racial caste system that generally encompassed all people of African descent, including those of mixed race. From 1662, Virginia defined social status by the status of the mother, unlike in England, where under common law fathers determined the status of their children, whether legitimate or natural. Thus, under the doctrine of partus sequitur ventrum, children born to enslaved mothers were considered slaves, regardless of their paternity. Similarly, children born to mothers who were free were also free, whether or not of mixed-race. At one time, Virginia had prohibited enslavement of Christian individuals, but lifted that restriction with its 1662 law. In the 19th century, laws were passed to restrict the rights of free people of color and mixed-race people (sometimes referred to as mulattoes) after early slave revolts. During the centuries of slavery in the British colonies, the number of mixed-race slaves increased.[76][79]

Slave rebellions

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| North American slave revolts |

|---|

|

Colonial slave rebellions before 1776, or before 1801 for Louisiana, include:

- San Miguel de Gualdape (1526)

- Gloucester County, Virginia Revolt (1663)[80]

- New York Slave Revolt of 1712

- Samba Rebellion (1731)

- Stono Rebellion (1739)

- New York Slave Insurrection of 1741

- 1791 Mina conspiracy

- Pointe Coupée conspiracy (1794)

16th century

[edit]While the British knew about Spanish and Portuguese slave trading, they did not implement slave labor in the Americas until the 17th century.[81] British travelers were fascinated by the dark-skinned people they found in West Africa; they developed mythologies that situated them in their view of the cosmos.[82] The first Africans to arrive in England came voluntarily in 1555 with John Lok (an ancestor of the famous philosopher John Locke). Lok intended to teach them English in order to facilitate the trading of material goods with West Africa.[83] This model gave way to a slave trade initiated by John Hawkins, who captured 300 Africans and sold them to the Spanish.[84] Blacks in England were marginalized but remained free, as slavery was never authorized by law in England.[85]

In 1607, the English established Jamestown as their first permanent colony on the North American continent.[86] Tobacco became the chief commodity crop of the colony, due to the efforts of John Rolfe in 1611. Once it became clear that tobacco was going to drive the Jamestown economy, more workers were needed for the labor-intensive crop. British plantation owners in North America and the Caribbean also needed a workforce for their cash crop plantations, which was initially filled by indentured servants from Britain before transitioning to Native American and West African slave labor.[87] During this period, the English established colonies in Barbados in 1624 and Jamaica in 1655. These and other Caribbean colonies generated wealth by the production of sugar cane, as sugar was in high demand in Europe. They also were an early center of the slave trade for the growing English colonial empire.[88]

English colonists entertained two lines of thought simultaneously toward indigenous Native Americans. Because these people were lighter-skinned, they were seen as more European and therefore as candidates for civilization. At the same time, because they were occupying the land desired by colonists, they were from the beginning, frequent targets of colonial violence.[89] At first, indentured servants were used for labor.[90] These servants provided up to seven years of service in exchange for having their trip to Jamestown paid for by someone in Jamestown. The person who paid was granted additional land in headrights, dependent on how many persons he paid to travel to the colony. Once the seven years were over, the indentured servant who survived was free to live in Jamestown as a regular citizen. However, colonists began to see indentured servants as too costly, in part because the high mortality rate meant the force had to be resupplied. In addition, an improving economy in England reduced the number of persons who were willing to sign up as indentured servants for the harsh conditions in the colonies.

17th century

[edit]In 1619, the English privateer White Lion, with Dutch letters of marque, brought 20 Africans seized Portuguese slave ship to Point Comfort.[91] Several colonial colleges held enslaved people as workers and relied on them to operate.[92]

The development of slavery in 17th-century America

[edit]

The laws relating to slavery and their enforcement hardened in the second half of the 17th century, and the prospects for Africans and their descendants grew increasingly dim. By 1640, the Virginia courts had sentenced at least one black servant, John Punch, to slavery.[93] In 1656 Elizabeth Key won a suit for freedom based on her father's status as a free Englishman, his having baptized her as Christian in the Church of England, and the fact that he established a guardianship for her that was supposed to be a limited indenture. Following her case, in 1662 the Virginia House of Burgesses passed a law with the doctrine of partus, stating that any child born in the colony would follow the status of its mother, bond or free. This overturned a long held principle of English common law, whereby a child's status followed that of the father. It removed any responsibility for the children from white fathers who had abused and raped slave women. Most did not acknowledge, support, or emancipate their resulting children.

During the second half of the 17th century, the British economy improved and the supply of British indentured servants declined, as poor Britons had better economic opportunities at home. At the same time, Bacon's Rebellion of 1676 led the planter class to worry about the prospective dangers of creating a large class of restless, landless, and relatively poor white men (most of them former indentured servants). Wealthy Virginia and Maryland planters began to buy slaves in preference to indentured servants during the 1660s and 1670s, and poorer planters followed suit by c.1700. (Slaves cost more than servants, so initially only the wealthy could invest in slaves.) The first European colonists in Carolina introduced African slavery into the colony in 1670, the year the colony was founded, and Charleston ultimately became the busiest slave port in North America. Slavery spread from the South Carolina Lowcountry first to Georgia, then across the Deep South as Virginia's influence had crossed the Appalachians to Kentucky and Tennessee. Northerners also purchased slaves, though on a much smaller scale. Enslaved people outnumbered free whites in South Carolina from the early 1700s to the Civil War. An authoritarian political culture evolved to prevent slave rebellion and justify white slaveholding. Northern slaves typically dwelled in towns, rather than on plantations as in the South, and worked as artisans and artisans' assistants, sailors and longshoremen, and domestic servants.[94]

In 1672, King Charles II of England rechartered the Royal African Company (which had been originally established in 1660), granting the company an exclusive monopoly on all English trade with Africa, which included the slave trade. This monopoly was overturned by an Act of Parliament in 1697.[95] The slave trade to the mid-Atlantic colonies increased substantially in the 1680s, and by 1710 the African population in Virginia had increased to 23,100 (42% of total); Maryland contained 8,000 Africans (23% of total).[96] During the early 18th century, Britain passed Spain and Portugal to become the world's leading slave-trading nation.[95][97]

The North American royal colonies not only imported Africans but also captured Native Americans, impressing them into slavery. Many Native Americans were shipped as slaves to the Caribbean. Many of these slaves from the British colonies were able to escape by heading south, to the Spanish colony of Florida. There they were given their freedom if they declared their allegiance to the King of Spain and accepted the Catholic Church. In 1739 Fort Mose was established by African-American freedmen and became the northern defense post for St. Augustine. The fort was destroyed during the War of Jenkins' Ear in 1740, though it was rebuilt in 1752. Because Fort Mose became a haven for escaped slaves from the Southern Colonies to the north, it is considered a precursor site of the Underground Railroad.[98]

Chattel slavery developed in British North America before the full legal apparatus that supported slavery did. During the late 17th century and early 18th century, harsh new slave codes limited the rights of African slaves and cut off their avenues to freedom. The first full-scale slave code in British North America was South Carolina's (1696), which was modeled on the colonial Barbados slave code of 1661. It was updated and expanded regularly throughout the 18th century.[99]

A 1691 Virginia law prohibited slaveholders from emancipating slaves unless they paid for the freedmen's transportation out of Virginia.[100] Virginia criminalized interracial marriage in 1691,[101] and subsequent laws abolished free blacks' rights to vote, hold office, and bear arms.[100] Virginia's House of Burgesses established the basic legal framework for slavery in 1705.[102]

The Atlantic slave trade to North America

[edit]Of the enslaved Africans brought to the New World an estimated 5–7% ended up in British North America. The vast majority of slaves transported across the Atlantic Ocean were sent to the Caribbean sugar colonies, Brazil, or Spanish America. Throughout the Americas, but especially in the Caribbean, tropical disease took a large toll on their population and required large numbers of replacements. Many Africans had limited natural immunity to yellow fever and malaria; but malnutrition, poor housing, inadequate clothing allowances, and overwork contributed to a high mortality rate.

In British North America, the enslaved population rapidly increased via the birth rate, whereas in the Caribbean colonies they did not. The lack of proper nourishment, being suppressed sexually, and poor health are possible reasons. Of the small numbers of babies born to slaves in the Caribbean, only about 1 in 4 survived the miserable conditions on sugar plantations. It was not only the major colonial powers of Western Europe such as France, Great Britain, Spain, Portugal, and the Dutch Republic that were involved. Other countries, including Sweden and Denmark–Norway, also participated in the Atlantic slave trade, though on a much more limited scale.

Sexual role differentiation and slavery

[edit]"Depending upon their age and gender, slaves were assigned a particular task, or tasks, that had to be completed during the course of the day."[103] In certain settings, men would participate in the hard labor, such as working on the farm, while women would generally work in the household. They would "be sent out on errands but in most cases their jobs required that they spend much of their time within their owner's household."[104] These gender distinctions were mainly applied in the Northern colonies and on larger plantations. In Southern colonies and smaller farms, however, women and men typically engaged in the same roles, both working in the tobacco crop fields for example.

Although slave women and men in some areas performed the same type of day-to-day work, "[t]he female slave ... was faced with the prospect of being forced into sexual relationships for the purpose of reproduction."[105] This reproduction would either be forced between one African slave and another, or between the slave woman and the owner. Slave owners saw slave women in terms of prospective fertility. That way, the number of slaves on a plantation could multiply without having to purchase another African. Unlike the patriarchal society of white Anglo-American colonists, "slave families" were more matriarchal in practice. "Masters believed that slave mothers, like white women, had a natural bond with their children that therefore it was their responsibility—more so than that of slave fathers—to care for their offspring."[106] Therefore, women had the extra responsibility, on top of their other day-to-day work, to take care of children. Men, in turn, were often separated from their families. "At the same time that slaveholders promoted a strong bond between slave mothers and their children, they denied to slave fathers their paternal rights of ownership and authority..."[106] Biological families were often separated by sale.

Indentured servitude

[edit]Some historians such as Edmund Morgan and Lerone Bennett have suggested that indentured servitude provided a model for slavery in the 17th-century Crown colonies. In practice, indentured servants were teenagers in England whose fathers sold their labor voluntarily for a period of time (typically four to seven years), in return for free passage to the colonies, room and board and clothes, and training in an occupation. After that, they received cash, clothing, tools, and/or land, and became ordinary settlers.

The Quaker petition against slavery

[edit]In 1688, four German Quakers in Germantown, a town outside Philadelphia, wrote a petition against the existence of slavery in the Province of Pennsylvania. They presented the petition to their local Quaker Meeting, and the Meeting was sympathetic, but could not decide what the appropriate response should be. The Meeting passed the petition up the chain of authority to the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting, where it continued to be ignored. It was archived and forgotten for 150 years.

The Quaker petition was the first public American document of its kind to protest slavery. It was also one of the first public declarations of universal human rights.[citation needed]

18th century

[edit]During the Great Awakening of the late eighteenth century, Methodist and Baptist preachers toured in the South, trying to persuade planters to manumit their slaves on the basis of equality in God's eyes. They also accepted slaves as members and preachers of new chapels and churches. The first black churches (all Baptist) in what became the United States were founded by slaves and free blacks in Aiken County, South Carolina, in 1773;[107] Petersburg, Virginia, in 1774; and Savannah, Georgia, in 1778, before the end of the Revolutionary War.[108][109]

Slavery was officially recognized as a serious offense in 1776 by the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting.[110][111][112] The Yearly Meeting had been against slavery since the 1750s.[113][114]

East Indian slaves

[edit]In the early 21st century, new research has revealed that small numbers of East Indians were brought to the Thirteen Colonies as slaves, during the period when both India and the colonies were under British control. As an example, an ad in the Virginia Gazette of August 4, 1768, describes one young "East Indian" as "a well made fellow, about 5 feet 4 inches high" who had "a thin visage, a very sly look, and a remarkable set of fine white teeth." Another slave is identified as "an East India negro man" who speaks French and English.[115] Most of the Indian slaves were already converted to Christianity, were fluent in English, and took western names.[115] Their original names and homes are not known, though some of them reportedly came from Bombay and Bengal.[116] Their descendants have mostly merged with the African-American community, which also incorporated European ancestors. Today, descendants of such East Indian slaves may have a small percent of DNA from Asian ancestors but it likely falls below the detectable levels for today's DNA tests, as most of the generations since would have been primarily of ethnic African and European ancestry.[117]

Beginning of the anti-slavery movement

[edit]African and African-American slaves expressed their opposition to slavery through armed uprisings such as the Stono Rebellion (1739) in South Carolina. More typically, they resisted through work slowdowns, tool-breaking, and running away, either for short periods or permanently. Until the Revolutionary era, almost no white American colonists spoke out against slavery. Even the Quakers generally tolerated slaveholding (and slave-trading) until the mid-18th century, although they emerged as vocal opponents of slavery in the Revolutionary era. During the Great Awakening, Baptist and Methodist preachers in the South originally urged planters to free their slaves. In the nineteenth century, they more often urged better treatment of slaves.[citation needed]

Further events

[edit]Late 18th and 19th centuries

[edit]During and following the Revolution, the northern states all abolished slavery, with New Jersey acting last in 1804. Some of these state jurisdictions enacted the first abolition laws in the entire New World.[118] In states that passed gradual abolition laws, such as New York and New Jersey, children born to slave mothers had to serve an extended period of indenture into young adulthood. In other cases, some slaves were reclassified as indentured servants, effectively preserving the institution of slavery through another name.[119]

Often citing Revolutionary ideals, some slaveholders freed their slaves in the first two decades after independence, either outright or through their wills. The proportion of free blacks rose markedly in the Upper South in this period, before the invention of the cotton gin created a new demand for slaves in the developing "Cotton Kingdom" of the Deep South.

By 1808 (the first year allowed by the Constitution to federally ban the import slave trade), all states (except South Carolina) had banned the international buying or selling of slaves. Acting on the advice of President Thomas Jefferson, who denounced the international trade as "violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa, in which the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country have long been eager to proscribe", in 1807 Congress also banned the international slave trade. However, the domestic slave trade continued in the South.[120] It brought great wealth to the South, especially to New Orleans, which became the fourth largest city in the country, also based on the growth of its port. In the antebellum years, more than one million enslaved African Americans were transported from the Upper South to the developing Deep South, mostly in the slave trade. Cotton culture, dependent on slavery, formed the basis of new wealth in the Deep South.

In 1844 the Quaker petition was rediscovered and became a focus of the burgeoning abolitionist movement.

Emancipation Proclamation and end of slavery in the US

[edit]On 1 January 1863, Abraham Lincoln signed Emancipation Proclamation freeing slaves in areas in rebellion during the American Civil War when Union troops advanced south. The Thirteenth Amendment (abolition of slavery and involuntary servitude) was ratified in December 1865.

Social and cultural developments during the colonial period

[edit]First slave laws

[edit]There were no laws regarding slavery early in Virginia's history, but, in 1640, a Virginia court sentenced John Punch, an African, to life in servitude after he attempted to flee his service.[121] The two whites with whom he fled were sentenced only to an additional year of their indenture, and three years' service to the colony.[122] This marked the first de facto legal sanctioning of slavery in the English colonies and was one of the first legal distinctions made between Europeans and Africans.[121][123]

| Date | Slaves |

|---|---|

| 1626–1650 | 824 |

| 1651–1675 | 0 |

| 1676–1700 | 3,327 |

| 1701–1725 | 3,277 |

| 1726–1750 | 34,004 |

| 1751–1775 | 84,580 |

| 1776–1800 | 67,443 |

| 1801–1825 | 109,545 |

| 1826–1850 | 1,850 |

| 1851–1875 | 476 |

| Total | 305,326 |

In 1641, the Massachusetts Bay Colony became the first colony to authorize slavery through enacted law.[67] Massachusetts passed the Body of Liberties, which prohibited slavery in many instances but allowed people to be enslaved if they were captives of war, if they sold themselves into slavery or were purchased elsewhere, or if they were sentenced to slavery as punishment by the governing authority.[67] The Body of Liberties used the word "strangers" to refer to people bought and sold as slaves; they were generally not English subjects. Colonists came to equate this term with Native Americans and Africans.[68]: 258–280

In 1654, John Casor, a black indentured servant in colonial Virginia, was the first man to be declared a slave in a civil case. He had claimed to an officer that his master, Anthony Johnson, had held him past his indenture term. Johnson himself was a free black, who had arrived in Virginia in 1621 from Portuguese Angola. A neighbor, Robert Parker, told Johnson that if he did not release Casor, he would testify in court to this fact. Under local laws, Johnson was at risk for losing some of his headright lands for violating the terms of indenture. Under duress, Johnson freed Casor. Casor entered into a seven years' indenture with Parker. Feeling cheated, Johnson sued Parker to repossess Casor. A Northampton County, Virginia court ruled for Johnson, declaring that Parker illegally was detaining Casor from his rightful master who legally held him "for the duration of his life".[125]

First inherited status laws

[edit]During the colonial period, the status of enslaved people was affected by interpretations related to the status of foreigners in England. England had no system of naturalizing immigrants to its island or its colonies. Since persons of African origins were not English subjects by birth, they were among those peoples considered foreigners and generally outside English common law. The colonies struggled with how to classify people born to foreigners and subjects. In 1656 Virginia, Elizabeth Key Grinstead, a mixed-race woman, successfully gained her freedom and that of her son in a challenge to her status by making her case as the baptized Christian daughter of the free Englishman Thomas Key. Her attorney was an English subject, which may have helped her case (he was also the father of her mixed-race son, and the couple married after Key was freed).[126]

In 1662, shortly after the Elizabeth Key trial and similar challenges, the Virginia royal colony approved a law adopting the principle of partus sequitur ventrem (called partus, for short), stating that any children born in the colony would take the status of the mother. A child of an enslaved mother would be born into slavery, regardless if the father were a freeborn Englishman or Christian. This was a reversal of common law practice in England, which ruled that children of English subjects took the status of the father. The change institutionalized the skewed power relationships between those who enslaved people and enslaved women, freed white men from the legal responsibility to acknowledge or financially support their mixed-race children, and somewhat confined the open scandal of mixed-race children and miscegenation to within the slave quarters.

First religious status laws

[edit]The Virginia slave codes of 1705 further defined as slaves those people imported from nations that were not Christian. Native Americans who were sold to colonists by other Native Americans (from rival tribes), or captured by Europeans during village raids, were also defined as slaves.[127] This codified the earlier principle of non-Christian foreigner enslavement.

First anti-slavery causes

[edit]

In 1735, the Georgia Trustees enacted a law prohibiting slavery in the new colony, which had been established in 1733 to enable the "worthy poor", as well as persecuted European Protestants, to have a new start. Slavery was then legal in the other 12 English colonies. Neighboring South Carolina had an economy based on the use of enslaved labor. The Georgia Trustees wanted to eliminate the risk of slave rebellions and make Georgia better able to defend against attacks from the Spanish to the south, who offered freedom to escaped enslaved people. James Edward Oglethorpe was the driving force behind the colony, and the only trustee to reside in Georgia. He opposed slavery on moral grounds as well as for pragmatic reasons, and vigorously defended the ban on slavery against fierce opposition from Carolina merchants of enslaved people and land speculators.[128][129][130]

The Protestant Scottish highlanders who settled what is now Darien, Georgia, added a moral anti-slavery argument, which became increasingly rare in the South, in their 1739 "Petition of the Inhabitants of New Inverness".[131] By 1750 Georgia authorized slavery in the colony because it had been unable to secure enough indentured servants as laborers. As economic conditions in England began to improve in the first half of the 18th century, workers had no reason to leave, especially to face the risks in the colonies.

Slavery in French Louisiana

[edit]

Louisiana was founded as a French colony. Colonial officials in 1724 implemented Louis XIV of France's Code Noir, which regulated the slave trade and the institution of slavery in New France and the French West Indies. This resulted in Louisiana, which was purchased by the United States in 1803, having a different pattern of slavery than the rest of the United States.[132] As written, the Code Noir gave some rights to slaves, including the right to marry. Although it authorized and codified cruel corporal punishment against slaves under certain conditions, it forbade slave owners from torturing them, separating married couples, or separating young children from their mothers. It also required owners to instruct slaves in the Catholic faith.[133][134]

Together with a more permeable historic French system that allowed certain rights to gens de couleur libres (free people of color), who were often born to white fathers and their mixed-race concubines, a far higher percentage of African Americans in Louisiana were free as of the 1830 census (13.2% in Louisiana compared to 0.8% in Mississippi, whose population was dominated by white Anglo-Americans). Most of Louisiana's "third class" of free people of color, situated between the native-born French and mass of African slaves, lived in New Orleans.[133] The Louisiana free people of color were often literate and educated, with a significant number owning businesses, properties, and even slaves.[134][135] Although Code Noir forbade interracial marriages, interracial unions were widespread. Whether there was a formalized system of concubinage, known as plaçage, is subject to debate. The mixed-race offspring (Creoles of color) from these unions were among those in the intermediate social caste of free people of color. The English colonies, in contrast, operated within a binary system that treated mulatto and black slaves equally under the law and discriminated against free black people equally, without regard to their skin tone.[132][135]

When the U.S. took over Louisiana, Americans from the Protestant South entered the territory and began to impose their norms. They officially discouraged interracial relationships (although white men continued to have unions with black women, both enslaved and free.) The "Americanization" of Louisiana gradually resulted in a binary system of race, causing free people of color to lose status as they were grouped with the slaves. They lost certain rights as they became classified by American whites as officially "black".[132][136]

Early abolitionism

[edit]The first voices to advocate the abolition of slavery were Puritans. For example, in 1700, Massachusetts judge and Puritan Samuel Sewall published "The Selling of Joseph," the first antislavery tract written in America.[137] In it, Sewall condemns slavery and the slave trade and refutes many of the era's typical justifications for slavery.[138][139]

The Puritan influence on slavery was still strong at the time of the American Revolution and beyond. In the decades leading up to the American Civil War, abolitionists such as Theodore Parker, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau and Frederick Douglass repeatedly used the Puritan heritage of the country to bolster their cause. The most radical anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, invoked the Puritans and Puritan values over a thousand times. Parker, in urging New England Congressmen to support the abolition of slavery, writes "The son of the Puritan ... is sent to Congress to stand up for Truth and Right ..."[140][141]

There was legal agitation against slavery in the Thirteen Colonies starting in 1752 by lawyer Benjamin Kent, whose cases were recorded by one of his understudies, the future president John Adams. Kent represented numerous slaves in their attempts to gain their freedom. He handled the case of a slave, Pompey, suing his master.[142] In 1766, Kent was the first lawyer in the United States to win a case to free a slave, Jenny Slew.[143] He also won a trial in the Old County Courthouse for a slave named Ceasar Watson (1771).[144] Kent also handled Lucy Pernam's divorce and the freedom suits of Rose and Salem Orne.[145]

In Massachusetts, slavery was successfully challenged in court in 1783 in a freedom suit by Quock Walker; he said that slavery was in contradiction to the state's new constitution of 1780 providing for equality of men. Freed slaves were subject to racial segregation and discrimination in the North, and in many cases they did not have the right to vote until ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870.[146]

See also

[edit]- Abolitionism in the United States

- American Descendants of Slavery (ADOS)

- Atlantic Creole

- Bristol slave trade

- Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

- Emancipation Proclamation

- Timeline of abolition of slavery and serfdom

- Colonial history of the United States

- Female slavery in the United States

- Free Negro

- Grand Model for the Province of Carolina

- History of labor law in the United States

- History of slavery in Connecticut

- History of slavery in Florida

- History of slavery in Georgia

- History of slavery in Maryland

- History of slavery in Massachusetts

- History of slavery in New Jersey

- History of slavery in New York

- History of slavery in Pennsylvania

- History of slavery in Rhode Island

- History of slavery in Virginia

- Indentured servitude in the Americas

- Mississippian shatter zone

- Scramble (slave auction)

- Seasoning (slavery)

- Slave Trade Act

- Slavery among Native Americans in the United States

- Slavery at common law

- Slavery in the British and French Caribbean

- Slavery in the Spanish New World colonies

- Slavery in the United States

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Ira Berlin, Generations of Captivity: A History of African-American Slaves (2003) pp. 272–276.

- ^ James A. Cox, "Bilboes, Brands, and Branks: Colonial Crimes and Punishments", Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Spring 2003.

- ^ E.g., Alisha Ebrahimji, "Slavery as a punishment for crimes is in the books in Ohio and lawmakers have been trying to change that for years", CNN, June 24, 2020; accessed 2021.10.18.

- ^ Oxford Journals (subscription required)Botzer, Tally (2017-08-15). "Myths and Misunderstandings: Slavery in the United States". American Civil War Museum. Retrieved 2020-07-04.

- ^ a b c d e Lauber, Almon Wheeler (1913). Indian Slavery in Colonial Times Within the Present Limits of the United States Chapter 1: Enslavement by the Indians Themselves. Vol. 53. New York: Columbia University. pp. 25–48. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Gallay, Alan (2009). "Introduction: Indian Slavery in Historical Context". In Gallay, Alan (ed.). Indian Slavery in Colonial America. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. pp. 1–32. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ Hoffman, Paul E. (1980). "A New Voyage of North American Discovery: Pedro de Salazar's Visit to the "Island of Giants"". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 58 (4): 415–426. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30140493.

- ^ a b c Peck, Douglas T. (2001). "Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón's Doomed Colony of San Miguel de Gualdape". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 85 (2): 183–198. ISSN 0016-8297. JSTOR 40584407.

- ^ a b c d Milanich, Jerald T. (2018). Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville: Library Press at UF. ISBN 978-1947372450. OCLC 1021804892.

- ^ Guitar, Lynne, No More Negotiation: Slavery and the Destabilization of Colonial Hispaniola's Encomienda System, by Lynne Guitar, retrieved 2019-12-06

- ^ Indian Slavery in the Americas – AP US History Study Guide from The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, 2012-03-22, retrieved 2019-12-06[dead link]

- ^ Lauber, Almon Wheeler (1913). "The Institution as Practiced by the English". Indian Slavery in Colonial Times Within the Present Limits of the United States. New York: Columbia University.

- ^ Gallay, Alan. (2002) The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717. Yale University Press: New York. ISBN 0300101937, p. 29

- ^ Gallay, Alan. (2002) The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717. Yale University Press: New York. ISBN 0300101937, pp. 187–190.

- ^ "Europeans did not introduce slavery or the notion of slaves as laborers to the American South but instead were responsible for stimulating a vast trade in humans as commodities." (p. 29) "In Native American societies, ownership of individuals was more a matter of status for the owner and a statement of debasement and "otherness" for the slave than it was a means to obtain economic rewards from unfree labor. … The slave trade was an entirely new enterprise for most people of all three culture groups [Native American, European, and African]." (p. 8) Gallay, Alan. (2002) The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717. Yale University Press: New York. ISBN 0300101937, p. 29

- ^ White, Richard. (1991) The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521424607

- ^ Ethridge, From Chicaza to Chickasaw (2010), p. 93.

- ^ Morgan, Edmund (1975). American Slavery, American Freedom. New York: W.W. Norton and Company. pp. 328–329. ISBN 978-0-393-32494-5.

- ^ Ethridge, From Chicaza to Chickasaw (2010), pp. 97–98.

- ^ Ethridge, From Chicaza to Chickasaw (2010), p. 109.

- ^ Ethridge, From Chicaza to Chickasaw (2010), p. 65.

- ^ Figures cited in Ethridge, From Chicaza to Chickasaw (2010), p. 237.

- ^ "Africans in America | African | Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ "malaria in Colonial America | Historia Obscura". Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ Phillips, Ulrich. American Negro Slavery (1918)

- ^ Lauber (1913), "The Number of Indian Slaves" [Ch. IV], in Indian Slavery, pp. 105–117.

- ^ Gallay, Alan. (2002) The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–171. New York: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300101937.

- ^ Reséndez, Andrés (2016). The other slavery: The uncovered story of Indian enslavement in America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 324. ISBN 978-0544947108.

- ^ Yarbrough, Fay A. (2008). "Indian Slavery and Memory: Interracial sex from the slaves' perspective". Race and the Cherokee Nation. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 112–123.

- ^ Castillo, E.D. 1998. "Short Overview of California Indian History" Archived 2006-12-14 at the Wayback Machine, California Native American Heritage Commission, 1998. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- ^ Castillo, E. D. 1998. "Short Overview of California Indian History" Archived December 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, California Native American Heritage Commission, 1998. Retrieved October 24, 2007.

- ^ Beasley, Delilah L. (1918). "Slavery in California," The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 3, No. 1. (January), pp. 33–44.

- ^ a b Bowman, Katherine (2002-03-04). "Slavery in Puerto Rico" (PDF). Hunter College. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-05-30. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Gallay, Alan. (2002) The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South 1670–1717. Yale University Press: New York. ISBN 0300101937, p. 299

- ^ Minchinton, Walter E. “The Seaborne Slave Trade of North Carolina.” The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 71, no. 1, 1994, pp. 1–61. JSTOR website Retrieved 16 Oct. 2023.

- ^ a b Cameron, Guy, and Stephen Vermette; Vermette, Stephen (2012). "The Role of Extreme Cold in the Failure of the San Miguel de Gualdape Colony". The Georgia Historical Quarterly. 96 (3): 291–307. ISSN 0016-8297. JSTOR 23622193.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Parker, Susan (2019-08-24). "'1619 Project' ignores fact that slaves were present in Florida decades before". St. Augustine Record. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ a b Francis, J. Michael; Mormino, Gary; Sanderson, Rachel (2019-08-29). "Slavery took hold in Florida under the Spanish in the 'forgotten century' of 1492-1619". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ a b Torres-Spelliscy, Ciara; Law, a fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of (2019-08-23). "Perspective – Everyone is talking about 1619. But that's not actually when slavery in America started". Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ Wood, Betty; et al. "Slavery in Colonial Georgia". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ a b c Chipman, Donald. "Estevanico". Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ^ "Before 1861", Florida Memory

- ^ Hankerson, Derek (2008-01-02). "The journey of Africans to St. Augustine, Florida and the establishment of the underground railway". Patriotic Vanguard. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ Gardner, Sheldon (2019-05-20). "St. Augustine's Fort Mose added to UNESCO Slave Route Project". St. Augustine record. Retrieved 2019-12-06.

- ^ a b "Fort Mose", "American Latino Heritage", National Park Service

- ^ "Plantations", Florida Memory

- ^ Teja, Jesús F. de la (1996). San Antonio de Béxar: a community on New Spain's northern frontier (1st ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0585276722. OCLC 45732379.

- ^ Williams, David A. (1997). Bricks without straw: a comprehensive history of African Americans in Texas (1st ed.). Austin, Tex.: Eakin Press. ISBN 0585242755. OCLC 44956931.

- ^ Deetz, Kelley Fanto (August 13, 2019). "400 years ago, enslaved Africans first arrived in Virginia". National Geographic. Archived from the original on August 13, 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ Waxman, Olivia B. (August 20, 2019). "Where the Landing of the First Africans in English North America Really Fits in the History of Slavery". Time. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ Finley, Ben (2019-08-22). "Virginia marks pivotal moment when African slaves arrived". Associated Press. Retrieved 2019-08-25.

- ^ https://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/feature/indentured-servants-in-the-us/, Indentured Servants In The U.S.

- ^ Austin, Beth (December 2019). 1619: Virginia's First Africans (Report). Hampton History Museum. pp. 12, 17–20.

- ^ "America and West Indies: September 1672." Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies: Volume 7, 1669-1674. Ed. W Noel Sainsbury. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1889. 404–417. British History Online. Web. 31 May 2021.

- ^ Edmund S. Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia (New York: Norton, 1975), pp.154–157.

- ^ Morgan, American Slavery, American Freedom, pp.327–328.

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), p. 78.

- ^ Foner, Phillip. "Slaves and Free Blacks in the Southern Colonies." History of Black Americans: From Africa to the Emergence of the Cotton Kingdom. Greenwood Press. 1975. (web archive access from October 14, 2013)

- ^ Gookin, Daniel (1836) [1677]. . Worcester, etc. hdl:2027/mdp.39015005075109. OCLC 3976964. archaeologiaame02amer.

But this shows the prudence and fidelity of the Christian Indians; yet notwithstanding all this service they were, with others of our Christian Indians, through the harsh dealings of some English, in a manner constrained, for want of shelter, protection, and encouragement, to fall off to the enemy at Hassanamesit, the story whereof follows in its place; and one of them, viz. Sampson, was slain in fight, by some scouts of our praying Indians, about Watchuset; and the other, Joseph, taken prisoner in Plymouth Colony, and sold for a slave to some merchants at Boston, and sent to Jamaica, but upon the importunity of Mr. Elliot, which the master of the vessel related to him, was brought back again, but not released. His two children taken prisoners with him were redeemed by Mr. Elliot, and afterward his wife, their mother, taken captive, which woman was a sober Christian woman and is employed to teach school among the Indians at Concord, and her children are with her, but her husband held as before, a servant; though several that know the said Joseph and his former carriage, have interceded for his release, but cannot obtain it; some informing authority that he had been active against the English when he was with the enemy.

- ^ Bodge, George Madison (1906). "Capt. Thomas Wheeler and his Men; with Capt. Edward Hutchinson at Brookfield". Soldiers in King Philip's War: Being a Critical Account of that War, with a Concise History of the Indian Wars of New England from 1620–1677 (Third ed.). Boston: The Rockwell and Churchill Press. p. 109. hdl:2027/bc.ark:/13960/t4hn31h3t. LCCN 08003858. OCLC 427544035.

Sampson was killed by some English scouts near Wachuset, and Joseph was captured and sold into slavery in the West Indies.

- ^ Bodge, George Madison (1906). "Appendix A". Soldiers in King Philip's War: Being a Critical Account of that War, with a Concise History of the Indian Wars of New England from 1620–1677 (Third ed.). Boston: The Rockwell and Churchill Press. p. 479. hdl:2027/bc.ark:/13960/t4hn31h3t. LCCN 08003858. OCLC 427544035.

Captives. The following accounts show the harsh custom of the times, and reveal a source of Colonial revenue not open to our country since that day. Account of Captives sold by Mass. Colony. August 24th, 1676. John Hull's Journal page 398.

- ^ Winiarski, Douglas L. (September 2004). Rhoads, Linda Smith (ed.). "A Question of Plain Dealing: Josiah Cotton, Native Christians, and the Quest for Security in Eighteenth-Century Plymouth County" (PDF). The New England Quarterly. 77 (3): 368–413. ISSN 0028-4866. JSTOR 1559824. OCLC 5552741105. Archived from the original on 2020-03-22.

While Philip and the vast majority of hostile Natives were killed outright during the war or sold into slavery in the West Indies, the friendly Wampanoag at Manomet Ponds retained their lands.

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Jared Ross Hardesty, "Creating an Unfree Hinterland: Merchant Capital, Bound Labor, and Market Production in Eighteenth-century Massachusetts." Early American Studies 15.1 (2017): 37–63.

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), p. 103.

- ^ a b c d e Higginbotham, A. Leon (1975). In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period. Greenwood Press. ISBN 9780195027457.

- ^ a b William M. Wiecek (1977). "the Statutory Law of Slavery and Race in the Thirteen Mainland Colonies of British America". The William and Mary Quarterly. 34 (2): 258–280. doi:10.2307/1925316. JSTOR 1925316.

- ^ a b Sammons, Mark J.; Cunningham, Valerie (2004). Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage. Durham, New Hampshire: University of New Hampshire Press. ISBN 978-1584652892. LCCN 2004007172. OCLC 845682328. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ^ Acts and laws of His Majesty's province of New-Hampshire, in New-England: With sundry acts of Parliament. Laws, etc. Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Daniel Fowle. 1759. p. 40.

- ^ a b Hodges, Russel Graham (1999). Root and Branch: African Americans in New York and East Jersey, 1613–1863. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ^ Shakir, Nancy. "Slavery in New Jersey". Slaveryinamerica. Archived from the original on 2003-10-17. Retrieved 2008-10-22.

- ^ Karnoutsos, Carmela. "Underground Railroad". Jersey City Past and Present. New Jersey City University. Retrieved 2011-03-27.

- ^ "The Hidden History of Slavery in New York". The Nation. ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 2016-10-11.

- ^ Ekberg, Carl J. (2000). French Roots in the Illinois Country. University of Illinois. pp. 2–3. ISBN 0252069242.

- ^ a b Martin H. Steinberg, Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management, pp. 725–726

- ^ Rodney Stark, "For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-hunts, and the End of Slavery", p.322 [1] Note that the hardcover edition has a typographical error stating "31.2 percent"; it is corrected to 13.2 in the paperback edition. The 13.2% value is confirmed with 1830 census data.

- ^ Cook, Samantha; Hull, Sarah (2011). The Rough Guide to the USA. Rough Guides UK. ISBN 9781405389525.

- ^ a b Jones, Terry L. (2007). The Louisiana Journey. Gibbs Smith. p. 115. ISBN 9781423623809.

- ^ Joseph Cephas Carroll, Slave Insurrections in the United States, 1800–1865, p. 13

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), p. 21. "Yet those in high places who advocated the overseas expansion of England did not propose that West Africans could, should, or would be enslaved by the English in the Americas. Indeed, West Africans scarcely figured at all in the sixteenth-century English agenda for the New World."

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), p. 23. "More than anything else it was the blackness of West Africans that at once fascinated and repelled English commentators. The negative connotations that the English had long attached to the color black were to deeply prejudice their assessment of West Africans."

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), p. 26. "It seems that these men were the first West Africans to set foot in England, and their arrival marked the beginning of a black British population. The men in question had come to England willingly. Lok's sole motive was to facilitate English trading links with West Africa. He intended that these five men should be taught English, and something about English commercial practices, and then returned home to act as intermediaries between the English and their prospective West African trading partners."

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), p. 27.

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), p. 28.

- ^ Wilford, John Noble (13 September 1996). "Jamestown Fort, 'Birthplace' Of America in 1607, Is Found". The New York Times.

- ^ Wood, Betty, The Origins of American Slavery: Freedom and Bondage in the English Colonies (1997), p. 18.

- ^ "British Involvement in the Transatlantic Slave Trade". The Abolition Project. E2BN – East of England Broadband Network and MLA East of England. 2009. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), pp. 34–39.

- ^ Barker, Deanna. "Indentured Servitude in Colonial America". Mert Sahinoglu. Frontier Resources.

- ^ "History & Culture – Fort Monroe National Monument". U.S. National Park Service). Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- ^ Wilder, Craig Steven (2014-09-02). Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America's Universities. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781608194025.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-07-31. Retrieved 2012-07-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Wilson, Thomas D. The Ashley Cooper Plan: The Founding of Carolina and the Origins of Southern Political Culture. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2016. Chapters 1 and 4.

- ^ a b "Africans in America | Part 1 | Narrative | from Indentured Servitude to Racial Slavery". PBS.

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), p. 88.

- ^ "European traders – International Slavery Museum, Liverpool museums".

- ^ "Aboard the Underground Railroad – Fort Mose Site". U.S. National Park Service.

- ^ Alan Taylor, American Colonies (New York: Viking, 2001), p. 213.

- ^ a b Alan Taylor, American Colonies (New York: Viking, 2001), p. 156.

- ^ America Past and Present Online – The Laws of Virginia (1662, 1691, 1705) Archived 2008-04-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wood, Origins of American Slavery (1997), p. 92. "In 1705, almost exactly a century after the first colonists had set foot in Jamestown, the House of Burgesses codified and systematized Virginia's laws of slavery. These laws would be modified and added to over the next century and a half, but the essential legal framework within which the institution of slavery would subsequently operate had been put in place."

- ^ Wood, Betty (January 1, 2005). Slavery in Colonial America. Rowman and Littlefield. p. 33.

- ^ Wood, Betty (2005). Slavery in Colonial America. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 39.

- ^ Hallam, Jennifer. "The Slave Experience: Men, Women, and Gender". PBS. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- ^ a b Stevenson, Brenda. "Distress and Discord in Virginia Slave Families, 1830–1860". In Joy and in Sorrow: Women, Family and Marriage in the Victorian South.

- ^ Raboteau, Albert J. (2004). Slave Religion: The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South. Oxford University Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-0195174137. Retrieved 28 May 2013.

- ^ Edward A. Hatfield, "First African Baptist Church", New Georgia Encyclopedia, 2009

- ^ Andrew Billingsley, Mighty Like a River: The Black Church and Social Reform (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003)

- ^ First formal protest against slavery filed in Pennsylvania in 1688, UCLA

- ^ African Presence in Pennsylvania

- ^ Slavery and anti-slavery; a history of the great struggle in both hemispheres, by William Goodell (abolitionist)

- ^ Revolution as Reformation – Protestant Faith in the Age of Revolutions, 1688–1832

- ^ Johns Hopkins University Studies in Historical and Political Science

- ^ a b Assisi, Francis C. (16 May 2007). "Indian Slaves in Colonial America". India Currents. Archived from the original (reprint) on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 2013-02-19.

- ^ https://www.nedhector.com/east-indians-enslaved-in-america/

- ^ Estes, Roberta (2012). "East India Indians in Early Colonial Records". Native Heritage Project.

- ^ Foner, Eric (2010). The Fiery Trial: Abraham Lincoln and American Slavery. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. p. 14.

- ^ Edgar J. McManus, A History of Negro Slavery in New York, Syracuse University Press, 1966

- ^ Dumas Malone, Jefferson and the President: Second Term, 1805–1809 (1974) pp. 543–44

- ^ a b Donoghue, John (2010). "Out of the Land of Bondage": The English Revolution and the Atlantic Origins of Abolition". The American Historical Review. Archived from the original on 2015-09-04.

- ^ Higginbotham, A. Leon (1975). In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process: The Colonial Period. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0195027457.

- ^ Tom Costa (2011). "Runaway Slaves and Servants in Colonial Virginia". Encyclopedia Virginia.

- ^ "Assessing the Slave Trade: Estimates". The Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database. Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia.

- ^ William J. Wood. "The Illegal Beginning of American Negro Slavery," American Bar Association Journal, January 1970.

- ^ Banks, Taunya (2008-01-01). "Dangerous Woman: Elizabeth Key's Freedom Suit - Subjecthood and Racialized Identity in Seventheenth Century Colonial Virginia". Faculty Scholarship.

- ^ Seybert, Tony (August 4, 2004). "Slavery and Native Americans in British North America and the United States: 1600 to 1865". Slavery in America. Archived from the original on August 4, 2004. Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- ^ Wilson, Thomas D., The Oglethorpe Plan: Enlightenment Design in Savannah and Beyond, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2012, chapter 3

- ^ Scott, Thomas Allan (July 1995). Cornerstones of Georgia history. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 978-0820317434.

- ^ "Thurmond: Why Georgia's founder fought slavery". Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved October 4, 2009.

- ^ "It is shocking to human Nature, that any Race of Mankind and their Posterity should be sentanc'd to perpetual Slavery; nor in Justice can we think otherwise of it, that they are thrown amongst us to be our Scourge one Day or other for our Sins: And as Freedom must be as dear to them as it is to us, what a Scene of Horror must it bring about! And the longer it is unexecuted, the bloody Scene must be the greater."

– Inhabitants of New Inverness, s:Petition against the Introduction of Slavery - ^ a b c Steinberg, Martin H.; Forget, Bernard G.; Higgs, Douglas R.; Nagel, Ronald L. (2001). Disorders of Hemoglobin: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63266-9.

- ^ a b Rodney Stark, For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-hunts, and the End of Slavery, p. 322 Internet Archive The hardcover edition has a typographical error stating "31.2 percent"; it is corrected to 13.2 in the paperback edition. The 13.2% value for the percentage of free people of color (see below) is confirmed with 1830 census data.

- ^ a b Cook, Samantha; Hull, Sarah (2011). The Rough Guide to the USA. Rough Guides UK. ISBN 978-1405389525.

- ^ a b Jones, Terry L. (2007). The Louisiana Journey. Gibbs Smith. ISBN 978-1423623809.

- ^ Stark, Rodney (2003). For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-hunts, and the End of Slavery. Princeton University Press. p. 322. ISBN 978-0691114361.

- ^ Bremer 1995, p. 208.

- ^ Sewall, pp. 1-3.

- ^ McCullough, pp. 132-133.

- ^ Gradert, pp. 1-3, 14-15, 24, 29-30.

- ^ Commager, pp. 206-210.

- ^ Hardesty, Jared Ross (2018). Unfreedom: Slavery and Dependence in Eighteenth-Century Boston. NYU Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-1479801848. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Jenny Slew: The first enslaved person to win her freedom via jury trial". Kentake Page. 2016-01-29. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Mand, Frank. "Ceasar Watson's tale highlight of 1749 Courthouse Thanksgiving ceremony". Wicked Local Plymouth. Archived from the original on 18 August 2021. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ Adams, Catherine; Pleck, Elizabeth (2010). Love of Freedom: Black Women in Colonial and Revolutionary New England. Oxford University Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-0199741786. Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ^ "Africans in America/Part 4/Narrative: Fugitive Slaves and Northern Racism". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2022-12-29.

Sources

[edit]- Bremer, Francis J. (1995). The Puritan Experiment: New England society from Bradford to Edwards (Revised ed.). University Press of New England. ISBN 978-0-87451-728-6.