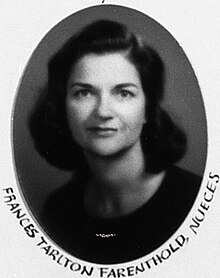

Frances Farenthold

Frances Farenthold | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Texas House of Representatives from the 45th district | |

| In office January 14, 1969 – January 9, 1973 | |

| Preceded by | Charles R. Scoggins |

| Succeeded by | John H. Poerner |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mary Frances Tarlton October 2, 1926 Corpus Christi, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | September 26, 2021 (aged 94) Houston, Texas, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

George Farenthold

(m. 1950; div. 1985) |

| Education | Vassar College (AB) University of Texas (JD) |

| Occupation | Educator, lawyer, politician, college administrator, activist |

Mary Frances Tarlton "Sissy" Farenthold (October 2, 1926 – September 26, 2021) was an American politician, attorney, activist, and educator. She was best known for her two campaigns for governor of Texas in 1972 and 1974, and for being placed in nomination for vice president of the United States, finishing second at the 1972 Democratic National Convention. She was elected as the first chair of the National Women's Political Caucus in 1973.[1]

Early life and education

[edit]Mary Frances Tarlton was born in Corpus Christi, Texas, on October 2, 1926, the daughter of Catherine (Bluntzer) and Benjamin Dudley Tarlton, Jr., a district attorney.[2] She was nicknamed "Sissy" as her slightly older brother could not yet pronounce the word sister.[2] After attending the Hockaday School,[3] Farenthold graduated from Vassar College in 1946. In 1949, she graduated from the University of Texas School of Law. She was one of only three women in a class of 800. Farenthold came from a line of lawyers and judges. Her grandfather, Judge Benjamin D. Tarlton Sr., served as chief justice of the Texas Court of Civil Appeals, a state legislator, professor at the University of Texas School of Law and as the namesake of the University of Texas School of Law Tarlton Law Library.[4][5]

Career

[edit]Politics

[edit]Farenthold started her political career in 1968, when she was elected to represent Nueces and Kleberg counties in the Texas House of Representatives. She ran against Jack K. Pedigo of Corpus Christi, Texas, graduate of the University of Michigan Law School and World War II veteran. She was the only woman serving in the Texas House at the time. Senator Barbara Jordan was then the only woman serving in the Texas Senate. They co-sponsored the Equal Legal Rights Amendment to the Texas Constitution.[5]

Farenthold was the third woman whose name was put into nomination for vice president of the United States at a major party's nominating convention. The first was Lena Springs, who was not a public official and whose 1924 nomination was a gesture of affection. The second was India Edwards in 1952, whose nomination was also a gesture of gratitude for her influence over Harry Truman. At the Democratic National Convention in 1972, Farenthold came in second to the presidential nominee's choice, U.S. Senator Thomas F. Eagleton of Missouri. She garnered more delegate votes (404.04) than Senator Mike Gravel of Alaska, Senator Birch Bayh of Indiana, and Governor Jimmy Carter of Georgia, among others.

In 1972, and 1974, she unsuccessfully sought the Democratic nomination for governor of Texas. She was defeated both times by Dolph Briscoe of Uvalde, who went on to win the general election each time. In 1973, she was elected as the first chair of the National Women's Political Caucus.[1] She later served as president of Wells College in Aurora, New York, from 1976 to 1980.

Farenthold founded the Public Leadership Education Network in 1978 with key support for her vision from Ruth Mandel, who directed the Center for American Women and Politics, which is a part of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University and Betsey Wright, who headed the National Women's Education Fund. The organization was founded on Farenthold's proposal that women's colleges needed to work together to educate and prepare women for public leadership.

Human rights work

[edit]During her tenure at Wells, Farenthold expanded her work with women’s groups and anti-nuclear, peace, and human rights groups. She was an active member of Helsinki Watch, the predecessor to the organization Human Rights Watch and Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.[6]

Farenthold left Wells College in 1980 to return to Houston, where she opened a private law practice and taught law at the University of Houston. She also continued to devote significant time to the international women’s movement and began a collaboration with her cousin, Genevieve Vaughan, that would last the next decade.[7]

Farenthold and Vaughan organized the Peace Tent at the 1985 U.N. NGO Forum in Nairobi, Kenya, in conjunction with the third United Nations World Conference on Women.[8] They also were founding members of Women For a Meaningful Summit, an ad hoc coalition of female leaders voicing concerns for nuclear disarmament at the Reagan–Gorbachev summits.[6] Farenthold worked with the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS), a progressive multi-issue think tank devoted to peace, justice, and the environment. With IPS, Farenthold made trips to investigate human rights violations in Central America and Iraq.

She was an emeritus trustee for the Institute for Policy Studies and served on the advisory board of the Bernard and Audre Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice at the University of Texas. She also served as honorary director of the Rothko Chapel in Houston.

Personal life

[edit]She married George Farenthold (1915–2000) in 1950, and divorced him in 1985. They had five children: Dudley (born 1951), George Jr. (born 1952), Emilie (born 1954), and twins Vincent Bluntzer Tarlton (1956–1960) and James Robert Dougherty (born 1956; disappeared 1989).[9] Her step-grandson, Blake Farenthold, was elected in 2010 to the U.S. House of Representatives from Texas as a Republican, and served as a member of the Tea Party Caucus until he resigned April 6, 2018, due to allegations he used $84,000 of taxpayer money to pay a settlement to a former aide who accused him of sexual harassment and other improper conduct.[10]

Death

[edit]Farenthold died from complications caused by Parkinson's disease on September 26, 2021, at the age of 94 at her home in Houston.[2][11]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "National Women's Political Caucus: History". Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c Fox, Margalit (September 27, 2021). "Frances T. Farenthold, Liberal Force in Texas and Beyond, Dies at 94". The New York Times. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Fields-Hawkins, Stephanie (December 2012). Frances Farenthold: Texas' Joan of Arc (Master of Arts thesis). University of North Texas.

- ^ Draper, Robert (April 1992). "The Blood of the Farentholds". Texas Monthly. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- ^ a b "A Guide to the Frances Tarlton Farenthold Papers, 1913–2016". Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, The University of Texas at Austin.

- ^ a b "Frances Tarlton "Sissy" Farenthold: A Noble Citizen". Bernard and Audre Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice, The University of Texas at Austin School of Law.

- ^ The Frances T. Farenthold Papers, The Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin

- ^ Vaughan, Genevieve (1984). "The Nairobi Peace Tent". Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ James Robert Dougherty Farenthold. CharleyProject.org, 2007. Retrieved September 22, 2013,

- ^ Diaz, Daniella (April 6, 2018). "Embattled Texas Republican Rep. Blake Farenthold resigns". CNN. Retrieved August 2, 2019.

- ^ Holley, Joe (September 26, 2021). "Frances 'Sissy' Farenthold, lodestar for Texas liberals, dies at 94". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 26, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Frances Tarlton "Sissy" Farenthold: A Noble Citizen, an online exhibit about Farenthold and her career, from the Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice at UT Austin

- A Guide to the Frances Tarlton Farenthold Papers The archival finding aid to Farenthold's physical papers at the Briscoe Center for American History at UT Austin.

- Institute for Policy Studies

- Oral History Interview with Frances Farenthold from Oral Histories of the American South

- The Bernard and Audre Rapoport Center for Human Rights and Justice

- Farenthold, Frances "Sissy" and Frank Michel. Frances "Sissy" Farenthold Oral History Archived October 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Houston Oral History Project, October 1, 2007.

- 1926 births

- 2021 deaths

- 20th-century American women politicians

- 21st-century American women

- American women academics

- Candidates in the 1972 United States elections

- Candidates in the 1974 United States elections

- Deaths from Parkinson's disease in the United States

- Female candidates for Vice President of the United States

- Heads of universities and colleges in the United States

- Hockaday School alumni

- Democratic Party members of the Texas House of Representatives

- Politicians from Corpus Christi, Texas

- University of Houston faculty

- Vassar College alumni

- Wells College faculty

- Women heads of universities and colleges

- Women state legislators in Texas

- Equal Rights Amendment activists

- 20th-century members of the Texas Legislature