John Murray of Broughton

Sir John Murray of Broughton, 7th Baronet of Stanhope | |

|---|---|

Modern Broughton Place; built on site of Murray's birthplace in 1935, based on the original 17th century design | |

| Jacobite Secretary of State | |

| In office August 1745 – May 1746 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 10 October 1715 Broughton, Peebleshire |

| Died | 6 December 1777 (aged 62) Cheshunt, Hertfordshire |

| Resting place | East Finchley Cemetery, London |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Spouse(s) | (1) Margaret Ferguson 1739–1749 (2) Miss Webb |

| Children | Numerous; including David (1743–1791), Robert (1745–1793), Lt-General Thomas Murray (ca 1749–1816) Charles Murray (1754–1821) |

| Parent(s) | Sir David Murray (ca 1652–1729) Margaret Scott |

| Alma mater | Edinburgh University Leiden University |

| Occupation | Politician and landowner |

Sir John Murray of Broughton, 7th Baronet of Stanhope (c. 1715 – 6 December 1777), also known as Murray of Broughton, was a Scottish baronet, who served as Jacobite Secretary of State during the 1745 Rising.

As such, he was responsible for Jacobite civilian administration, and was by contemporary accounts hardworking and efficient. Captured in June 1746 after the Battle of Culloden, he gave evidence against Lord Lovat, who was later executed. Much of his testimony was directed against those who promised to support the Rising, but failed to do so.

Released in 1748, he retired into a life of relative obscurity until his death in 1777. Although denounced as a traitor by some of his former colleagues, he retained his Jacobite beliefs and was one of the few to remain on good terms with Prince Charles.

Biography

[edit]

John Murray was born in Broughton, in Peeblesshire, the younger son of Sir David Murray and his second wife Margaret Scott. His father took part in the 1715 Rising but was pardoned and thereafter focused on restoring the family fortunes. In 1726, he sold his estates in Broughton, investing the proceeds in purchasing lands in Ardnamurchan and lead mines at Strontian.[1]

In 1739, Murray married Margaret, daughter of Colonel Robert Ferguson of Nithsdale, who served with the Cameronians, a regiment originally recruited from militant Presbyterians in 1689.[2] They had five children, including three sons, David (1743–1791), Robert (1745–1793) and Lt-General Thomas Murray (ca 1749–1816).[3]

Margaret was reportedly one of the beauties of her time and they divorced sometime before 1749, after accusations of adultery on both sides. Murray later formed a relationship with 'a young Quaker lady named Webb, whom he found in a provincial boarding-school in England.' Although it is unclear whether they ever married, they had six children, the most noteworthy being actor and dramatist Charles Murray (1754–1821).[4]

His nephew Sir David, fourth baronet of Stanhope, also took part in the 1745 Rising and lost both lands and title; pardoned on condition he went into exile, he died in Livorno in 1752. The title of Baronet of Stanhope was restored in the 1760s and eventually passed to Murray in 1770, then to his eldest son David in 1777.[4]

Career

[edit]Pre-1745

[edit]Murray attended the University of Edinburgh from 1732 to 1735, before enrolling at the University of Leiden in the Dutch Republic. In 1737, he embarked on the 18th century cultural excursion known as the Grand Tour; this included Rome, one of whose attractions was the exiled James Stuart.[5] The Jacobite cause had been largely dormant since the 1719 Rising and when Murray met him, James was living quietly in Rome "having abandoned all hope of a restoration."[6]

Most visitors contented themselves with seeing the exiled court, but in August, Murray was admitted to the Masonic lodge in Rome, whose members included James Edgar, private secretary to James. The Lodge was later described by historian Andrew Lang as 'a nest of Jacobites', and this seems to be the origin of Murray's career as a Jacobite activist.[7]

Murray returned to Scotland in December 1738, where he married Margaret Ferguson, and repurchased the family estate of Broughton, later sold in 1764 to James Dickson, a wealthy merchant and Member of Parliament.[8] In 1741, the Duke of Hamilton approved his appointment as principal Jacobite agent in Scotland, following the death of Colonel James Urquhart.[9]

The outbreak of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1740 placed Britain and France on opposing sides and Murray made frequent visits to Paris, carrying messages between Scottish Jacobites and Lord Sempil, the Stuart agent in Paris. Defeat at Dettingen in June 1743 prompted Louis XV to look for ways to divert British resources, including a proposed invasion of England in early 1744 to restore the Stuarts. Charles secretly joined the invasion force in Dunkirk, but the expedition was cancelled in March after the French fleet was severely damaged by winter storms.[10]

In August, Charles travelled to Paris to persuade the French to support another attempt, where he met Murray, telling him he was "determined to come to Scotland, though with a single footman".[11] Back in Edinburgh, Murray shared this news with the pro-Jacobite Buck Club, whose members included James, later 6th Duke of Hamilton and Lord Elcho. Murray and other members wrote to Charles, urging him not to come unless he brought 6,000 French troops, money and weapons.[4] The letter was given to the 5th Earl of Traquair (1699–1764) for delivery, but he apparently failed to do so.[12]

Secretary Murray; the 1745 Rising

[edit]

In late June, Murray learned Charles was preparing to sail from France and waited in Western Scotland for three weeks, hoping to dissuade him from landing. He eventually gave up and was at home when news came of their arrival at Eriskay on 23 July; when Charles refused to return to France, Murray agreed to become Secretary. This made him responsible for civilian administration and finances, a major issue, as Charles had less than £50 in cash. One method was to collect taxes 'on behalf of the government'; many towns paid twice, as the state refused to recognise their validity, and in 1753, Paisley sued Murray for £500 levied in 1745.[13]

The Jacobite army marched on Edinburgh, reaching Perth on 3 September, where they were joined by Lord George Murray. After participating in the 1715 and 1719 Risings, he was pardoned in 1725 and settled down to life as a Scottish country gentleman; his elder brother Tullibardine accompanied Charles to Scotland but his son was a British army officer. His defection surprised both sides and many Jacobites viewed him with suspicion, not helped by his poorly concealed view of Charles as a 'reckless adventurer.'[14] Murray was later blamed for the frequent clashes between Charles and his senior Scottish commander, but even his admirers recorded Lord George's talents were offset by a quick temper, arrogance and inability to take advice.[15]

Murray accompanied the army into England and helped negotiate the surrender of Carlisle in November. As he was not part of the Prince's War Council, he avoided responsibility for the decision to retreat at Derby; this marked a major deterioration in the relationship between Charles and the Scots, Murray being one of the few to retain his trust.[16] After abandoning the siege of Stirling in early February, the Jacobites retreated to Inverness; in March, Murray fell ill and was replaced by the far less capable John Hay of Restalrig.[4]

Money and basic items like shoes were now so short soldiers were paid in oatmeal and supplies requisitioned from local shopkeepers.[17] When the campaign reopened in April, the leadership decided only a decisive victory could retrieve their position, but were defeated at the Battle of Culloden. Charles ordered his troops to disperse until he returned from France with additional support.[18]

In early May, two French privateers arrived in Loch nan Uamh, bringing 35,000 gold coins packed in seven barrels for the Jacobite war effort. With the Royal Navy close behind, the money was hastily landed and the French ships fought their way out, carrying a number of senior officers, including Lord John Drummond and the Duke of Perth.[19] Murray was in Leith seeking passage to Holland with Lochiel and his younger brother Archibald Cameron when they heard of the ships arrival. Hoping to use these funds to continue the war, the three travelled to Loch nan Uamh and took charge of the money, although one barrel was missing.[20]

What happened to the rest is unclear; Murray claimed some was distributed in back pay and the bulk consigned to Archibald Cameron for safekeeping, which agrees with the detailed account provided by Cameron in 1750.[21] In the recriminations that followed defeat, various people were accused of stealing it, including Cameron, executed in 1753 after returning to Scotland allegedly to dig it up, Alastair MacDonnell, aka Pickle the spy, who spent the Rising in the Tower of London and MacPherson of Cluny. Despite suggestions it remains hidden, modern-day treasure hunters have yet to find any trace of it.[22]

A few days later, Lochiel, Murray, Glenbucket, John Roy Stewart and others met near Loch Morar to discuss options. They were joined by Lord Lovat, who had avoided active participation himself, while ordering 300 clansmen led by his son Simon to take part. All agreed to reassemble a few days later, using the French money to pay their men, although Lovat asked for his share to be given to his 'steward'. Murray implies this was simply a ruse, and when they met up again a few days later, many did not attend at all, including the Frasers.[11]

Plans to continue the fight were abandoned and with government forces searching for them, the group split up. Still hoping to arrange passage from Leith and suffering from severe dysentery, Murray made his way to his sister's house at Polmood, where he was arrested on 27 June. In early July, he was transferred to the Tower of London, along with other senior Jacobites, including Lovat, who had been captured in early June.[23] Lochiel, Archibald Cameron, Glenbucket and others were picked up by a French ship in September.[24]

Trial and later life

[edit]

Prior to the 1744 invasion attempt, James had given Murray an officer's commission. At his trial, he claimed this allowed him to be treated as a prisoner of war, rather than a rebel, an argument rejected by the court. Francis Towneley, commander of the Manchester Regiment, was executed on 30 July despite being a major with eight years service in the French army.[25]

Most high-ranking Jacobite prisoners had been sentenced before Murray arrived in London but he agreed to provide information in return for a pardon. While some accounts claim Murray's testimony led to Lovat's execution, it was primarily used to confirm details of the evidence; Lovat's participation was not in dispute and many contemporaries felt his execution was long overdue. In October 1745, Lovat had attempted to kidnap his long-term associate Duncan Forbes, the chief legal officer in Scotland, who wrote that his motive was to 'ruin and subvert the government, because they (would not) gratify his...avaricious passions and desires.'[26]

Of far greater long-term significance was Murray's testimony against sympathisers who failed to support the Rising, although he avoided incriminating those he had not met, like the Duke of Beaufort, known to be "a most determined and unwavering Jacobite."[27] As with Lovat, he largely confirmed details already known, such as the meeting between Charles and Sir John Douglas, MP for Dumfriesshire at Stirling in January 1746. Two of his brothers served in the Jacobite army so Douglas' sympathies were hardly unknown, but Murray stated he was surprised to see him, 'never having suspected him to be in the Pretender's interest.'[28]

Although no action was taken against Douglas and others, this ended the practice whereby many British politicians could in theory support the overthrow of their own government with impunity.[29] The Tory Jacobite Williams-Wynn shows why this was considered necessary; on various occasions prior to 1745, he assured the Stuarts of his support for an invasion, then spent the Rising in London. Despite this, he wrote to Charles in late 1747 claiming his supporters wished for 'another happy opportunity wherein they may exert themselves more in deeds than in words, in the support of your Royal Highness's dignity and interest and the cause of liberty.'[30]

Released from the Tower after Lovat's execution, Murray was formally pardoned in June 1748 and disappeared into obscurity. He purchased a property in Cheshunt, outside London, where he was reportedly visited by Charles in 1763, remarried and had another six children. He was allegedly treated for alcoholism on a number of occasions; he succeeded his nephew David as Baronet of Stanhope in 1770 and died at home in December 1777.

Assessment

[edit]

Assessing Murray is complicated by the fact that arguments over responsibility for the Rising's failure reflected deep divisions within the Jacobite camp. Maxwell of Kirkconnel and Lord Elcho both accused him of deliberately poisoning relations between Charles and Lord George Murray, but Maxwell in particular detested Murray and cannot be viewed as an impartial witness.[4]

In the notes to their 1930 edition of Lord Pitsligo's Letters, the Taylers claim Murray was strongly in favour of the...expedition to Scotland, and made the utmost of all the promises of support, which he poured into the ready ear of Charles....[31] All the available evidence shows Charles was determined to make the attempt even before meeting Murray, despite being strongly urged not to do so by nearly everyone he contacted.[32]

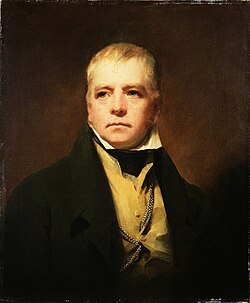

Most accusations of 'treachery' came from individuals like Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, who failed to follow through on promises of support; Murray later wrote 'virtue [may be] admired and Esteemed even by those who have not the fortitude to pursue it.'[33] Many anecdotes come from Tales of a Grandfather, a history of Scotland written for his grandson in 1828 by novelist Sir Walter Scott; while its timeline of events is broadly accurate, few of his stories can be verified.[34]

Those most often quoted include the allegation that when asked if he knew Murray, Douglas responded 'once I knew...a Murray of Broughton, but that was a gentleman and a man of honour.' The other claims Murray used to visit Scott's father, who was his lawyer, and that after each meeting, his father would threw anything used by Murray out of the window, exclaiming "I may admit into my house...persons wholly unworthy to be treated as guests... Neither lip of me nor of mine comes after Mr. Murray of Broughton's."[35] Neither have any basis in fact, and most of Scott's stories about the Rising are entirely fictitious.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Murray 1898, p. 24.

- ^ "Fergusson of Caitloch". Ferguson DNA Project. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Cohen.

- ^ a b c d e f Nicholson 2006.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Blaikie 1916, p. xlix.

- ^ Lang 1907, p. 314.

- ^ Namier & Brooke 1964, p. 322.

- ^ Way 1994, pp. 336–337.

- ^ Harding 2013, p. 171.

- ^ a b Murray 1898, p. 93.

- ^ Wemyss 1907, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Rowands.

- ^ McLynn 1983, p. 46.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Riding 2016, pp. 304–305.

- ^ Annand 1994, p. 72.

- ^ Stuart, Charles Edward (28 April 1746), Letter from Prince Charles Edward Stuart to the Scottish Chiefs, justifying his reasons for leaving Scotland after the Battle of Culloden (letter), RA SP/MAIN/273/117

- ^ Murray 1898, p. 388.

- ^ Zimmerman 2003, p. 27.

- ^ "Dr. Archibald Cameron's Memorial Concerning the Locharkaig Treasure (Stuart Papers, Vol. 300, No. 80) circa 1750". Clan Cameron. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Cowie.

- ^ Riding 2016, p. 462.

- ^ Riding 2016, p. 493.

- ^ Riding 2016, p. 474.

- ^ Riding 2016, p. 496.

- ^ Walpole 1833, p. 29th March 1745.

- ^ Murray 1898, pp. 436–437.

- ^ Zimmerman 2003, p. 202.

- ^ Cruickshanks 1970.

- ^ Tayler & Tayler 1930, p. 12.

- ^ Stephens 2010, p. 51.

- ^ Murray 1898, p. 252.

- ^ Shaw.

- ^ Lockhart 1842, p. 49.

Sources

[edit]- Annand, A Mck (1994). "Lord Kilmarnock's Horse Grenadiers (Later Foot Guards), in the Army of Prince Charles Edward, 1745-6". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 72 (290).

- Blaikie, Walter Biggar (1916). Origins of the 'Forty-Five, and Other Papers Relating to That Rising. T. and A. Constable. OCLC 2974999.

- Cohen, Jeffrey. "Sir John Murray of Stanhope, Baronet". Geni.com. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Cowie, Ashley. "Jacobite Gold". Ashley Cowie. Archived from the original on 6 May 2019. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- Cruickshanks, Eveline (1970). WILLIAMS (afterwards WILLIAMS WYNN), Watkin (?1693–1749), of Wynnstay, Denbighshire in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1715–1754. HMSO.

- Harding, Richard (2013). The Emergence of Britain's Global Naval Supremacy: The War of 1739–1748. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1843838234.

- Lang, Andrew (1907). The History Of Scotland – Volume 4: From the massacre of Glencoe to the end of Jacobitism (2016 ed.). Jazzybee Verlag. ISBN 978-3849685652.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Lockhart, John Gibson (1842). Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott. Palala Press. ISBN 978-1357265618.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - McLynn, FJ (1983). The Jacobite Army in England, 1745-46: The Final Campaign. John Donald Publishers. ISBN 978-0859760935.

- Murray, John (1898). Bell, Robert Fitzroy (ed.). Memorials of John Murray of Broughton: Sometime Secretary to Prince Charles Edward, 1740-1747. T. and A. Constable at the Edinburgh University Press for the Scottish History Society. OCLC 879747289.

- Namier, Lewis; Brooke, John (1964). The House of Commons 1754–1790. Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-0436304200.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Nicholson, Eirwen (2006). "Murray, Sir John, of Broughton, baronet [called Secretary Murray, Mr Evidence Murray". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/19629. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites: A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1408819128.

- Rowands, David. "Paisley in a panic". Paisley. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Shaw, Frank. "Review of 'Scotland; Story of a Nation'". Electrics Scotland. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- Stephens, Jeffrey (2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism: The Edinburgh Council, 1745". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1).

- Tayler, Alistair; Tayler, Henrietta, eds. (1930). Jacobite Letters to Lord Pitsligo 1745–1746. Milne & Hutchison.

- Walpole, Horace (1833). Letters to Sir Horace Mann. 28027933: G Dearborn.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Way, George (1994). The Collins Scottish Clan Encyclopedia. Collins. ISBN 978-0004705477.

- Wemyss, David, Lord Elcho (1907). Charteris, Evan (ed.). A Short Account of the Affairs of Scotland. David Douglas, Edinburgh.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Zimmerman, Doron (2003). The Jacobite Movement in Scotland and in Exile, 1746–1759. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403912916.