Sigma-pi and equivalent-orbital models

The σ-π model and equivalent-orbital model refer to two possible representations of molecules in valence bond theory. The σ-π model differentiates bonds and lone pairs of σ symmetry from those of π symmetry, while the equivalent-orbital model hybridizes them. The σ-π treatment takes into account molecular symmetry and is better suited to interpretation of aromatic molecules (Hückel's rule), although computational calculations of certain molecules tend to optimize better under the equivalent-orbital treatment.[1] The two representations produce the same total electron density and are related by a unitary transformation of the occupied molecular orbitals; different localization procedures yield either of the two. Two equivalent orbitals h and h' can be constructed by taking linear combinations h = c1σ + c2π and h' = c1σ – c2π for an appropriate choice of coefficients c1 and c2.

In a 1996 review, Kenneth B. Wiberg concluded that "although a conclusive statement cannot be made on the basis of the currently available information, it seems likely that we can continue to consider the σ/π and bent-bond descriptions of ethylene to be equivalent.[2] Ian Fleming goes further in a 2010 textbook, noting that "the overall distribution of electrons [...] is exactly the same" in the two models.[3] Nevertheless, as pointed out in Carroll's textbook, at lower levels of theory, the two models make different quantitative and qualitative predictions, and there has been considerable debate as to which model is most useful conceptually and pedagogically.[4]

Multiple bonds

[edit]Two different explanations for the nature of double and triple covalent bonds in organic molecules were proposed in the 1930s. Linus Pauling proposed that the double bond in ethylene results from two equivalent tetrahedral orbitals from each atom,[5] which later came to be called banana bonds or tau bonds.[6] Erich Hückel proposed a representation of the double bond as a combination of a sigma bond plus a pi bond.[7][8][9] The σ-π representation is the better-known one, and it is the one found in most textbooks since the late-20th century.

Multiple lone pairs

[edit]

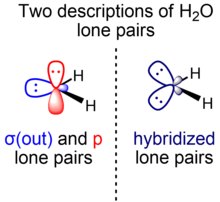

Initially, Linus Pauling's scheme of water as presented in his hallmark paper on valence bond theory consists of two inequivalent lone pairs of σ and π symmetry.[5] As a result of later developments resulting partially from the introduction of VSEPR, an alternative view arose which considers the two lone pairs to be equivalent, colloquially called rabbit ears.[10]

Weinhold and Landis describe the symmetry adapted use of the orbital hybridization concept within the context of natural bond orbitals, a localized orbital theory containing modernized analogs of classical (valence bond/Lewis structure) bonding pairs and lone pairs.[11] For the hydrogen fluoride molecule, for example, two F lone pairs are essentially unhybridized p orbitals of π symmetry, while the other is an spx hydrid orbital of σ symmetry. An analogous consideration applies to water (one O lone pair is in a pure p orbital, another is in an spx hybrid orbital).

The question of whether it is conceptually useful to derive equivalent orbitals from symmetry-adapted ones, from the standpoint of bonding theory and pedagogy, is still a controversial one, with recent (2014 and 2015) articles opposing[12] and supporting[13] the practice.

References

[edit]- ^ Peter B. Karadakov; Joseph Gerratt; David L. Cooper; Mario Raimondi (1993), "Bent versus .sigma.-.pi. bonds in ethene and ethyne: the spin-coupled point of view", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 115 (15): 6863–6869, doi:10.1021/ja00068a050.

- ^ Wiberg, Kenneth B. (1996), "Bent Bonds in Organic Compounds", Acc. Chem. Res., 29 (5): 229–34, doi:10.1021/ar950207a.

- ^ Fleming, Ian (2010), Molecular Orbitals and Organic Chemical Reactions (reference ed.), London: Wiley, p. 61, ISBN 978-0-470-74658-5.

- ^ A., Carroll, Felix (2010). Perspectives on structure and mechanism in organic chemistry (2nd ed.). Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley. ISBN 9780470276105. OCLC 286483846.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pauling, Linus (1931), "The nature of the chemical bond. Application of results obtained from the quantum mechanics and from a theory of paramagnetic susceptibility to the structure of molecules", J. Am. Chem. Soc., 53 (4): 1367–1400, doi:10.1021/ja01355a027.

- ^ Wintner, Claude E. (1987), "Stereoelectronic effects, tau bonds, and Cram's rule", J. Chem. Educ., 64 (7): 587, Bibcode:1987JChEd..64..587W, doi:10.1021/ed064p587.

- ^ Hückel, E. (1930), "Zur Quantentheorie der Doppelbindung", Z. Phys., 60 (7–8): 423–456, Bibcode:1930ZPhy...60..423H, doi:10.1007/BF01341254

- ^ Penney, W. G. (1934), "The Theory of the Structure of Ethylene and a Note on the Structure of Ethane", Proceedings of the Royal Society, A144 (851): 166–187, Bibcode:1934RSPSA.144..166P, doi:10.1098/rspa.1934.0041

- ^ Penney, W. G. (1934), "The Theory of the Stability of the Benzene Ring and Related Compounds", Proceedings of the Royal Society, A146 (856): 223–238, Bibcode:1934RSPSA.146..223P, doi:10.1098/rspa.1934.0151.

- ^ Laing, Michael (1987). "No rabbit ears on water. The structure of the water molecule: What should we tell the students?". J. Chem. Educ. 64 (2): 124–128. Bibcode:1987JChEd..64..124L. doi:10.1021/ed064p124.

- ^ Weinhold, Frank; Landis, Clark R. (2012). Discovering Chemistry with Natural Bond Orbitals. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-1-118-11996-9.

- ^ Clauss, Allen D.; Nelsen, Stephen F.; Ayoub, Mohamed; Moore, John W.; Landis, Clark R.; Weinhold, Frank (2014-10-08). "Rabbit-ears hybrids, VSEPR sterics, and other orbital anachronisms". Chemistry Education Research and Practice. 15 (4): 417–434. doi:10.1039/C4RP00057A. ISSN 1756-1108.

- ^ Hiberty, Philippe C.; Danovich, David; Shaik, Sason (2015-07-07). "Comment on "Rabbit-ears hybrids, VSEPR sterics, and other orbital anachronisms". A reply to a criticism". Chemistry Education Research and Practice. 16 (3): 689–693. doi:10.1039/C4RP00245H. S2CID 143730926.