Hoddesdon

| Hoddesdon | |

|---|---|

| Town | |

Hoddesdon Town Centre | |

Location within Hertfordshire | |

| Population | 42,253 (2011 Census, Built-up area sub division)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TL365085 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | HODDESDON |

| Postcode district | EN11 |

| Dialling code | 01992 |

| Police | Hertfordshire |

| Fire | Hertfordshire |

| Ambulance | East of England |

| UK Parliament | |

Hoddesdon (/ˈhɒdzdən/) is a town in the Borough of Broxbourne, Hertfordshire, lying entirely within the London Metropolitan Area and Greater London Urban Area. The area is on the River Lea and the Lee Navigation along with the New River.

Hoddesdon is the second most populated town in Broxbourne with a population of 42,253 according to the United Kingdom's 2011 census.[2]

It borders Ware to the north, Nazeing in Essex to the east, and Broxbourne to the south. The Prime Meridian passes just to the east of Hoddesdon. The town is served by Rye House railway station and nearby Broxbourne railway station.

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]The name "Hoddesdon" is believed to be derived from a Saxon or Danish personal name combined with the Old English suffix "don", meaning a down or hill.[3] The earliest historical reference to the name is in the Domesday Book within the hundred of Hertford.[4]

Hoddesdon was situated about 20 miles (32 km) north of London on the main road to Cambridge and to the north. The road forked in the centre of the town, with the present High Street dividing into Amwell Street and Burford Street, both leading north to Ware.[5] From an early date there were a large number of inns lining the streets to serve the needs of travellers. A market charter was granted to Robert Boxe, lord of the manor, in 1253.[3][5][6] By the 14th century the Hospital of St Laud and St Anthony had been established in the south of Hoddesdon. The institution survived the dissolution of the monasteries, but had ceased to exist by the mid 16th century, although it is commemorated in the name of Spital Brook which divides Hoddesdon from Broxbourne.[5]

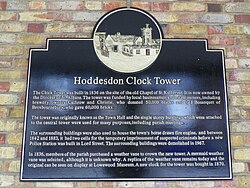

In 1336 William de la Marche was licensed to build a chapel of ease in the town. The building, known as St Katharine's Chapel, was used by pilgrims to the shrine at Walsingham.[3] It survived until the 17th century, when it was demolished. In 1835, a single-storey building, known as Hoddesdon Town Hall, was built on the site: only the clock tower now survives.[7]

The town was considerably enlarged in the reign of Elizabeth I, and a number of inns in the High Street date from this time.[3] The monarch granted a royal charter in 1559/60, placing the town government under a bailiff, warden and eight assistants. The charter also established a free grammar school based on the site of the former hospital, and this was placed under the care of the corporation. Neither the borough nor the school flourished, however, and both had ceased to exist by the end of the century.[5] In 1567 Sir William Cecil acquired the manor of Hoddesdonsbury and two years later Elizabeth granted him the neighbouring manor of Baas. From that date the Cecils maintained a connection with the town which is recorded by the naming of The Salisbury Arms (anciently the Black Lion Inn) : the title Marquess of Salisbury was granted to James Cecil in 1789.

In 1622 Sir Marmaduke Rawdon built Rawdon House, a red-brick mansion which still survives. Rawdon also provided the town with its first public water supply, flowing from a statue known as the "Samaritan Woman".[3][5][8]

In 1683 there was an alleged Whig conspiracy to assassinate or mount an insurrection against Charles II of England because of his pro-Roman Catholic policies. This plot was known as the Rye House Plot, named from Rye House at Hoddesdon, near which ran a narrow road where Charles was supposed to be killed as he travelled from a horse meeting at Newmarket. By chance, according to the official narrative, the king's unexpectedly early departure in March foiled the plot. Ten weeks later, on 1 June, an informer's allegations prompted a government investigation.[9]

The subsequent history of Rye House has been considerably less dramatic. In 1870 the current owner, William Henry Teale, opened a pleasure garden, displaying the Great Bed of Ware, which he had recently acquired. It was such a popular destination for excursions from London that an extra station was built on the Liverpool Street to Hertford East line to serve it.[10]

By the early 20th century, however, the tourist trade had fallen off, and Rye House was demolished, apart from the Gatehouse; the Great Bed was moved to the Victoria & Albert Museum.[10]

Rye House Gatehouse still stands today, and is now a Grade 1 listed building.[11] It is open to the public at weekends and bank holidays during the summer, featuring displays about the Plot and the early history of brick-building. The rest of the grass-covered site has the floor-plan of the house marked out.[10]

A new chapel of ease, dedicated to St Paul, was built in 1732.[12] This was subsequently enlarged, and in 1844 become the parish church when Hoddesdon was created a separate ecclesiastical parish.[5] Previously the town had been divided between the two parishes of Broxbourne and Great Amwell. The boundary between the two parishes ran through an archway in the town's High Street. When this building was demolished in the 1960s, a specially inscribed stone was set into the pavement marking the historic boundary.[13]

Brewing was first established in the town in about 1700. In 1803, William Christie established a brewery in the town, and it became a major employer and one of the largest breweries in England. The brewery continued in operation until 1928.[14] Most of the brewery buildings were demolished in 1930, although part was converted into a cinema itself since demolished. Some remnants of the establishment remain in Brewery Road.[15]

By the mid-19th century the town still consisted principally of one street, and had a population of 1,743. Malt was being produced and transported to London via the River Lea. There were also a number of flour mills.[16] Trade in Hoddesdon was centred on the hops market each Thursday. As time went on, more and more hops were carried on the river rather than the roads and the Wednesday meat market took predominance. The Wednesday market has survived and a Friday market was added in the late 20th century.

After the Second World War

[edit]After the Second World War Hoddesdon increasingly became a dormitory town, forming part of the London commuter belt. Much of the town centre was demolished in the 1960s and 1970s, with the construction of the Tower Centre and Fawkon Walk shopping centres. The opening of a bypass in 1974 changed the nature of the town, with through traffic curtailed.[3]

Hoddesdon has a sizeable Italian community.[17] Many Sicilian families emigrated to the Lea Valley in the 1950s and 60s to work in the nearby garden nurseries, and they and many of their descendants still live in the area. Since the 18th century the Lea Valley has had a reputation for fine produce from its market gardens and green houses. The owners and growers of the majority of the Lea Valley's cucumber farms come primarily from two villages in Sicily: Cianciana and Mussomeli.[18] The Lee Valley Growers Association estimates that more than 70% of the 100 or so nurseries in the Lea Valley are now owned by Sicilian descendants, producing 75% of UK-grown cucumbers and 50% of its peppers in their glasshouses.[17]

Part of a wave of immigration to the UK after the Second World War, the Italian community has grown to become part of the fabric of the area, with migrants and their descendants still celebrating their rich Italian heritage.[17] The Festival of San Antonio is celebrated in June with a street procession, although nowadays it is a low-key festival since many of the participants are elderly.[19]

In 1951 Hoddesdon was the seemingly unlikely location for the eighth meeting of CIAM (Congrès Internationaux d'Architecture Moderne), referred to as CIAM 8, which was an international organization of the world's most significant architects and town planners of the time. The participants gathered in the High Leigh country house in Hoddesdon to discuss the theme "The Heart of the City", a response to issues regarding cities badly damaged during World War Two.[20]

Recent changes

[edit]In 2007 Rye House Kart Raceway was taken over by two local family businessmen. It was recently described as the "Silverstone of Karting" by David Coulthard. The Book It Now diary based calendar system was developed here in 2013.

In 2014 JD Wetherspoon's first pub in Hoddesdon opened at the former Salisbury Arms on the High Street. During renovations at the renamed Star, a series of important 16th century wall paintings was uncovered. They are located on the north wall of the bar, with some additional detail found on one of the beams supporting the ceiling. The paintings depict half-figures and biblical verses.[21] Roof beams dating to the mid-1400s have also been revealed, suggesting that The Star is older than previously thought.[22]

Governance

[edit]Hoddesdon has two tiers of local government, at district (borough) and county level: Broxbourne Borough Council and Hertfordshire County Council. There has been no parish or town council for Hoddesdon since 1974.

| Hoddesdon | |

|---|---|

| Urban District (1894-1974) | |

Council Offices, High Street, Hoddesdon | |

| Population | |

| • 1901 | 4,711 |

| • 1971 | 25,880[23] |

| History | |

| • Created | 31 December 1894 |

| • Abolished | 31 March 1974 |

| • Succeeded by | Broxbourne |

| • HQ | Hoddesdon |

| Contained within | |

| • County Council | Hertfordshire |

Hoddesdon was formerly classed as a hamlet within the parish of Broxbourne. A separate ecclesiastical parish of Hoddesdon was created in 1844, but for civil purposes the town continued to straddle Broxbourne and Great Amwell parishes.[24] The hamlet of Hoddesdon had its own overseers of the poor and from 1835 appointed its own guardians to the Ware Poor Law Union.[25] As such, the hamlet of Hoddesdon became a civil parish on 10 August 1866 with the passing of the Poor Law Amendment Act 1866.[26]

Hoddesdon was included in the Ware Rural Sanitary District from 1872. Under the Local Government Act 1894 rural sanitary districts were converted into rural districts, but before that Act came into force an order was made to convert Hoddesdon into an urban district. A new parish called "Hoddesdon Urban" was created from most of the old Hoddesdon parish and part of Great Amwell, whilst the sparsely populated western part of Hoddesdon became a separate parish called Hoddesdon Rural, which became part of Ware Rural District. Hoddesdon Urban District Council came into being on 31 December 1894.[27]

On 1 April 1935 a County Review Order enlarged the urban district. The neighbouring parishes of Broxbourne, Hoddesdon Rural, and Wormley were all abolished, with most of their territory being absorbed into the parish and urban district of Hoddesdon. Parts of the parishes of Great Amwell and Stanstead Abbotts were transferred into Hoddesdon at the same time. Much of the western boundary of the urban district then coincided with the track of the Roman Ermine Street.[28]

In its early years, Hoddesdon Urban District Council met at the Coffee Tavern Hall on Lord Street.[29][30] In 1936 the council built itself a new building called Council Offices at the southern end of the High Street. The Council Offices were formally opened on 21 December 1936, and remained the headquarters of the council until its abolition.[31]

Hoddesdon Urban District was abolished under the Local Government Act 1972, merging with Cheshunt Urban District on 1 April 1974 to become the Borough of Broxbourne. No successor parish was created for the town. The former offices of Hoddesdon Urban District Council were converted to residential use in 1988 and renamed Belvedere Court.[31]

Education

[edit]- The John Warner School is a community, foundation comprehensive for 11- to 18-year-olds.

- Sheredes School served the area from 1969. In 2012 Sheredes received the artsmark gold award in recognition of the outstanding work in the arts and was one of only a handful of schools nationally to have been awarded this for a fourth time. In 2016 Sheredes became Robert Barclay Academy, a comprehensive school for 11- to 18-year-olds. John Warner has specialist status in science and sport and Sheredes was well regarded in the arts.

In 2007 the John Warner School received congratulations from Mr Jim Knight, Minister of State for Education for being placed 24th in the '100 most improved schools in the country'. This award is a combination of eight years continuous improvement in examination results.

Sport and leisure

[edit]As well as the array of shops in and around Hoddesdon, there are a number of leisure activities in the local area, including a gym in the town centre and the John Warner sports centre, a leisure centre on the outskirts of the town containing a swimming pool and children's activity centre. There is also a Non-League football club Hoddesdon Town F.C., which plays at Lowfield, and a large go-kart track located in nearby Rye park. Around a mile north of the town is Rye House Stadium, home until recently of the Rye House Rockets speedway team.

Media

[edit]The town is within the BBC London and ITV London region. Television signals are received from the Crystal Palace TV transmitter [32] Local radio stations are BBC Three Counties Radio, Heart Hertfordshire and Mix 92.6. The town is served by the local newspaper, Hoddesdon & Broxbourne Mercury which is published by the Hertfordshire Mercury.[33]

Transport

[edit]Railway

[edit]Greater Anglia operates local services. The nearest railway stations to the town are:[34]

- Broxbourne on the West Anglia Main Line, with services between Cambridge North and London Liverpool Street, and between Hertford East and Liverpool Street.

- Rye House is on the Hertford East Branch Line with services between Hertford East and Liverpool Street.

Roads

[edit]

Hoddesdon contains a small part of Ringway 4, part of the 1960s London Ringways scheme and the only part built north of London further east than Watford.

Linking the town to the A10, the A1170 Dinant Link Road has an overly large junction between the link road and the A10; it was built with space available to continue the road westward over the A10.

Buses

[edit]Local bus services are operated primarily by Arriva Herts & Essex, Central Connect, Centrebus (South), Epping Forest Community Transport and Uno. Routes connect Hoddesdon with Broxbourne, Harlow, Hatfield, Hertford, Stevenage, Waltham Cross and Ware.[35]

Notable people

[edit]- Harriet Auber (1773–1862), poet, hymnist

- Arthur James Balfour, 1st Earl of Balfour (1848–1930), Conservative politician and prime minister of the United Kingdom 1902 – 1905. Attended the Grange Preparatory School, Hoddesdon.[36]

- Francis Maitland Balfour (1851–1882), comparative embryologist and morphologist, younger brother of the above, also attended Grange School.[37]

- William Ellis (1794–1872), missionary and author. Lived in the town from 1844, and served as a minister to an Independent congregation. Died at his residence on 9 June 1872.[38]

- William Christie Gosse (1842–1881), explorer and surveyor, was born in Hoddesdon, emigrated to Australia in 1850. In 1859 he entered the Government service of South Australia.[39]

- John Hoole (1727–1803), translator, attended school in Hoddesdon.[40]

- William Josiah Irons (1812–1883), Church of England clergyman and theological writer. Born in Hoddesdon 12 September 1812.[41]

- John Loudon McAdam (1756–1836), engineer and roadbuilder lived in the town from 1827.[42]

- Hugh Paddick (1915–2000), comedy actor, born in Hoddesdon.[43]

- Colin Pratt (1938–2021), former motorcycle speedway rider.

- Richard Rumbold (c 1622–1685), Cromwellian soldier and conspirator in the Rye House Plot.[44]

- Lena Zavaroni (1963–1999), popular singer and entertainer spent some of her final years in Hoddesdon and is buried in Hoddesdon Cemetery.[45]

- Erik Thorstvedt (1962), Norwegian footballer, played for Tottenham Hotspur between 1989 and 1996. Lived in Hoddesdon during his time at Tottenham.[46]

- David Tree (1915–2009), English stage and screen actor, and nationally prominent commercial grower in Hoddesdon for over sixty years.

- Gino D'Acampo (1976), Italian-British celebrity chef, currently lives in Hoddesdon.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Hoddesdon Built-up area sub division". NOMIS. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "Cheshunt (Hertfordshire, East of England, United Kingdom) - Population Statistics, Charts, Map, Location, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Sue Garside (2008). "Hoddesdon". Rotary Club of Hoddesdon. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ Open Domesday Online: Hoddesdon

- ^ a b c d e f William Page, ed. (1912). "Parishes: Broxbourne with Hoddesdon". A History of the County of Hertford: volume 3. British History Online. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ "Markets and fairs". Lowewood Museum. 2008. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ Historic England. "Clock Tower (1296010)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Samaritan Woman in Hoddesdon". Lowewood Museum. 2008. Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ "Rye House Plot | English history". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ a b c (www.communitysites.co.uk), Community Sites. "A historic Hoddesdon house | Rye House | Historic Houses | Places | Herts Memories". www.hertsmemories.org.uk. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ Historic England. "Rye House Gatehouse (1341877)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ Historic England. "Parish Church of St Paul, Amwell Street (1100533)". National Heritage List for England.

- ^ "Hoddesdon Heritage Guide" (PDF). Retrieved 10 April 2023.

- ^ "Christie Photo Album". Lowewood Museum. 1 June 2007. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ Allen Eyles and Keith Scone, Cinemas of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, 2003

- ^ Samuel Lewis, ed. (1848). "Hoddesdon". A Topographical Dictionary of England. British History Online. Retrieved 18 July 2008.

- ^ a b c "Lee Valley little Sicily". Hertfordshire. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ "Olympics 2012: The Sicilian cucumber connection". Telegraph.co.uk. 4 August 2012. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ San Antonio Festival Archived 12 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved

- ^ Eric Paul Mumford, The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000, p. 202. Hoddesdon was regarded as an unlikely location by its cosmopolitan participants because previous CIAM meetings had been held in renowned cities such as Paris, Athens and Brussels.

- ^ "16th century wall paintings uncovered at former Salisbury Arms, Hoddesdon could be of 'national importance'". Hertfordshire Mercury. Archived from the original on 23 December 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ "Wetherspoon's first Hoddesdon pub, The Star, to open on December 16". Hertfordshire Mercury. Archived from the original on 28 July 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- ^ "Hoddesdon Urban District, A Vision of Britain through Time". GB Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

- ^ "At the Court at Windsor, the 10th of November 1843, London Gazette". London Gazette (20301): 1. 2 January 1844. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ Higginbotham, Peter. "Ware Poor Law Union". The Workhouse. Retrieved 1 January 2022.

- ^ "Poor Law Amendment Act 1866 (29 & 30 Victoria, c. 113)". A collection of the public general statutes passed in the twenty-ninth and thirtieth years of the reign of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. London. 1866. pp. 574–577. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Annual Report of the Local Government Board. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. 1895. p. 255. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

The County of Hertford (Hoddesdon, &c.) Confirmation Order, 1894

- ^ Ministry of Health Order No. 80108. The County of Hertford Review Order 1935

- ^ Kelly's Directory of Hertfordshire. London. 1899. p. 130. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kelly's Directory of Hertfordshire. London. 1914. p. 161. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Local List. Cheshunt: Broxbourne Borough Council. December 2011. p. 70. Retrieved 2 January 2022.

Former Council Offices: Belvedere Court, High Street, Hoddesdon

- ^ "Full Freeview on the Crystal Palace (Greater London, England) transmitter". UK Free TV. 1 May 2004. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "Hoddesdon & Broxbourne Mercury". British Papers. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 13 January 2024.

- ^ "Timetables". Greater Anglia. 2 June 2024. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ "Hoddesdon bus services". Bustimes.org. Retrieved 4 December 2024.

- ^ Ruddock Mackay; H. C. G. Matthew (2004). "Balfour, Arthur James, first earl of Balfour (1848–1930)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30553. Retrieved 17 July 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Brian K Hall (2004). "Balfour, Francis Maitland (1851–1882)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1186. Retrieved 17 July 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Norman Etherington (2004). "Ellis, William (1794–1872)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8720. Retrieved 17 July 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "William Christie Gosse (1842–1881)". Gosse, William Christie (1842–1881). Australian National University. 2006. Retrieved 29 December 2008.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Vivienne W Painting (2004). "Hoole, John (1727–1803)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/13703. Retrieved 17 July 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ G C Boase (2004). "Irons, William Josiah (1812–1883)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/14459. Retrieved 17 July 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Brenda J Buchanan (2004). "McAdam, John Loudon (1756–1836)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17325. Retrieved 17 July 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ "Obituary: Hugh Paddick". The Independent. 17 November 2000. Archived from the original on 28 September 2008. Retrieved 17 July 2008.

- ^ Robin Clifton (2004). "Rumbold, Richard (c1622–1685)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/24269. Retrieved 17 July 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ John Van der Kiste (2004). "Zavaroni, Lena Hilda (1963–1999)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/73110. Retrieved 17 July 2008. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Bolme, Magnus. "Erik Thorstvedt". Norsk biografisk leksikon (in Norwegian). Kunnskapsforlaget. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

External links

[edit]- "Hoddesdon Society Website". Hoddesdon Society. Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2009.