Sexism: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tag: gettingstarted edit |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

{{lead too short|date=December 2013}} |

{{lead too short|date=December 2013}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Feminism sidebar}} |

|||

{{Discrimination sidebar}} |

{{Discrimination sidebar}} |

||

Revision as of 21:43, 30 March 2014

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

Sexism or gender discrimination is prejudice or discrimination based on a person's sex or gender.[1] Sexist attitudes may stem from traditional stereotypes of gender roles,[2][3] and may include the belief that a person of one sex is intrinsically superior to a person of the other.[4] A job applicant may face discriminatory hiring practices, or (if hired) receive unequal compensation or treatment compared to that of their opposite-sex peers.[5] Extreme sexism may foster sexual harassment, rape and other forms of sexual violence.[6]

Origin of the term

According to Fred R. Shapiro, in American Speech (Vol. 60, No. 1, Spring 1985), the term "sexism" was most likely coined on November 18, 1965, by Pauline M. Leet during the Student-Faculty Forum at Franklin and Marshall College.[7] The term appears in Leet's forum contribution titled "Women and the Undergraduate", in which she defines it by comparing it to racism, saying in part, "When you argue…that since fewer women write good poetry this justifies their total exclusion, you are taking a position analogous to that of the racist — I might call you in this case a "sexist"… Both the racist and the sexist are acting as if all that has happened had never happened, and both of them are making decisions and coming to conclusions about someone’s value by referring to factors which are in both cases irrelevant."[7]

Also according to Shapiro, the first time the term "sexism" appeared in print was in Caroline Bird's speech "On Being Born Female", which was published on November 15, 1968, in Vital Speeches of the Day (p. 6).[7] In this speech she said in part, "There is recognition abroad that we are in many ways a sexist country. Sexism is judging people by their sex when sex doesn’t matter. Sexism is intended to rhyme with racism. Both have used to keep the powers that be in power."[7]

Sheldon Vanauken is sometimes falsely claimed to have coined the term "sexism" in his pamphlet "Freedom for Movement Girls – Now".[7] In the pamphlet the term "sexism" appears without any citation of Leet or Bird, thus leading to the false idea that Vanauken coined it himself.[7]

History

Certain forms of sex discrimination are illegal in some countries; in others, discrimination may be legally sanctioned under a variety of circumstances.[8]

Ancient world

According to Peter Stearns, women in pre-agricultural societies held equal positions with men; it was only after the adoption of agriculture and sedentary cultures that men began to institutionalize the concept that women were inferior to men.[9] Definitive examples of sexism in the ancient world included written laws preventing women from participating in the political process; for example, Roman women could not vote or hold political office.[10]

Witch hunts and trials

Throughout history, women accused of witchcraft have been targeted by religious and state authorities, subjected to violence, prosecuted, and executed. The witch trials in the early modern period were a period of witch hunts between the 15th and 18th centuries,[12] when across early modern Europe[13] and to some extent in the European colonies in North America, there were widespread claims that malevolent Satanic witches were operating as an organized threat to Christendom. Several authors argue that the widespread misogyny of that period played a role in the persecution of these women.[14][15]

In Malleus Malificarum, the book which played a major role in the witch hunts and trials, the authors argue that women are more likely to practice witchcraft than men, and write that:

- All wickedness is but little to the wickedness of a woman ... What else is woman but a foe to friendship, an inescapable punishment, a necessary evil, a natural temptation, a desirable calamity, a domestic danger, a delectable detriment, an evil of nature, painted with fair colours![16]

Today, practicing witchcraft remains illegal in several countries, including Saudi Arabia, where it is punishable by death; and in 2011 a woman was beheaded in that country for 'witchcraft and sorcery'.[17]

Coverture and other marriage regulations

Until the 20th century U.S. and English law observed the system of coverture, where "by marriage, the husband and wife are one person in law; that is the very being or legal existence of the woman is suspended during the marriage".[18] U.S. women were not legally defined as "persons" until 1875 (Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162).[19]

In France married women received the right to work without their husband's permission in 1965,[20][21][22] and in West Germany women obtained this right in 1977 (women in East Germany enjoyed more rights).[23][24] In Spain during the Franco era a married woman required her husband's consent (permiso marital) for nearly all economic activities, including employment, ownership of property and traveling away from home; the permiso marital was abolished in 1975.[25]

In many countries, women still lose significant legal rights at marriage. For example, Yemeni marriage regulations state that a wife must obey her husband and must not leave home without his permission.[26]

In Iraq husbands have a legal right to "punish" their wives. The criminal code states at Paragraph 41 that there is no crime if an act is committed while exercising a legal right; examples of legal rights include: "The punishment of a wife by her husband, the disciplining by parents and teachers of children under their authority within certain limits prescribed by law or by custom".[27]

In the Democratic Republic of Congo the Family Code states that the husband is the head of the household; the wife owes her obedience to her husband; a wife has to live with her husband wherever he chooses to live; and wives must have their husbands' authorization to bring a case in court or to initiate other legal proceedings.[28]

Gender stereotypes

Gender stereotypes are widely held beliefs about the characteristics and behavior of women and men.[29] Empirical studies have found widely shared cultural beliefs that men are more socially valued and more competent than women in a number of activities.[30][31] For example, Susan Fiske and her colleagues surveyed nine diverse samples from different regions of the United States. Fiske found that members of these samples, regardless of age, consistently rated the category of "men" higher than the category of "women" on a multidimensional scale of competence.[32] Dustin B. Thoman and others (2008) hypothesize that “The socio-cultural salience of ability versus other components of the gender-math stereotype may impact women pursuing math”. Through the experiment comparing the math outcomes of women under two various gender-math stereotype components, which are the ability of math and the effort on math respectively, Thoman and others found that women’s math performance is more likely to be affected by the negative ability stereotype, which is influenced by socio-cultural beliefs in the United States, rather than the effort component. As a result of this experiment and the socio-cultural beliefs in the United States, Thoman and others concluded that individuals’ academic outcomes can be affected by the gender-math stereotype component that is influenced by the socio-cultural beliefs (Thoman et al. 2008).[33]

There are huge areal differences in attitudes towards appropriate gender roles. For example, in the World Values Survey, responders were asked if they thought that wage work should be restricted to only men in the case of shortage in jobs. While in Iceland the proportion that agreed was 3.6%, in Egypt it was 94.9%.[34]

Some people believe a phenomenon known as stereotype threat can lower women's performance on mathematics tests, creating a self-fulfilling stereotype of women having inferior quantitative skills compared to men.[35][36] Stereotypes can also affect self-assessment; studies found that specific stereotypes (e.g., women have lower mathematical abilities) affect women's and men’s perceptions of those abilities, and men assess their own task ability higher than women who perform at the same level. These "biased self-assessments" have far-reaching effects, because they can shape men and women’s educational and career decisions.[37][38]

Gender stereotypes

Gender roles are behaviors and tasks which society associates with each gender. In the United States, men are typically expected to be stoic, decisive, direct, athletic, strong, driven, and brave; women are expected to be emotional, nurturing, weak, affectionate, home-oriented and forgiving.[39]

According to the OECD, women's labor-market behavior "is influenced by learned cultural and social values that may be thought to discriminate against women (and sometimes against men) by stereotyping certain work and life styles as 'male' or 'female'". The organization contends that women's educational choices "may be dictated, at least in part, by their expectations that [certain] types of employment opportunities are not available to them, as well as by gender stereotypes that are prevalent in society".[40]

Professional discrimination against women in the workplace continues. One study found that 50 percent of women in government jobs reported that they had experienced discrimination while performing a work-related task, and 20 percent of female government employees reported that they experienced gender discrimination at work.[41] Women do not receive equal pay for equal work, and are less likely to be promoted.[42]

In 1833, women working in factories earned one-quarter of what men earned; in 2007, women's median annual paychecks were $0.78 for every $1.00 earned by men. A study showed that women comprised 87% of workers in the child-care industry, and 86 percent of the health-aide industry.[43] Others contest the wage gap, saying the difference in pay primarily reflects different career and work-hours choices by men and women rather than sexism.[44]

A 2009 study found that being overweight harms women's career advancement, but presents no barrier for men. Overweight or obese women were significantly underrepresented among company bosses; however, a significant proportion[quantify] of male executives were overweight or obese. The author of the study stated that the results suggest that "the 'glass ceiling effect' on women's advancement may reflect not only general negative stereotypes about the competencies of women, but also weight bias that results in the application of stricter appearance standards to women. Overweight women are evaluated more negatively than overweight men. There is a tendency to hold women to harsher weight standards."[45][46]

Transgender people also experience workplace discrimination and harassment.[47] Unlike sex-based discrimination, the refusal to hire (or firing) a worker for their gender identity or expression is legal in most countries and U.S. states.

In language

Sexism in language exists when language helps to devalue members of a certain sex and thus fosters gender inequality, reinforcing ideas of gender-based dominance.[48] What is now termed sexist language often promotes the idea of inherently male superiority, resulting in discrimination against women.[49]

Sexism in language has arisen as a topic of concern as academics have pointed to the role that language plays in articulating consciousness, ordering our reality, encoding and transmitting cultural meanings and affecting socialization.[48] Researchers have pointed to the semantic rule in operation in language of the male-as-norm.[50] This results in sexism as the male becomes the standard and those who are not male are relegated to the inferior.[50] Examples include the use of generic masculine words which refer to all humanity, like man, master, father, and brother. Other examples include the use of the singular masculine pronoun (he, his, him). Further examples point to terms ending in 'man' that may be performed by individuals of either sex, such as businessman, chairman, policeman. Finally, ordering of words also relegates women to an inferior position, in examples like "man and wife". Sexism in language is considered a form of indirect sexism, in that it is not always overt.[51]

Sexist and gender-neutral language

Various feminist movements in the 20th century, from liberal feminism and radical feminism to standpoint feminism, postmodern feminism and queer theory have all considered language in their theorizing.[52] Most of these theories have maintained a critical stance on language that call on a change in the way speakers use their language. One of the most common calls is for gender-neutral language. Many have called attention, however, to the fact that the English language isn't inherently sexist in its linguistic system, but rather the way it is used becomes sexist and gender-neutral language could thus be employed.[53] At the same time, other oppose critiques of sexism in language with explanations that language is a descriptive, rather than prescriptive, and attempts to control it can be fruitless.[54]

Sexism in languages other than English

Languages other than English are also charged with sexism in language.

In the French language, for example, due to pressure from several feminist groups, the word 'mademoiselle', meaning miss was declared banished in 2012 by Prime Minister François Fillon.[55] Current pressure calls for the use of the masculine plural pronoun as the default in a mixed-sex group to change.[56]

In Chinese, some writers have pointed to sexism inherent in the structure of written characters. For example, the character for man is linked to those for positive qualities like courage and effect while the character for wife is composed of a female part and a broom, considered of low worth.[57]

Spanish has also been accused of sexist structures, in that the masculine form is the default form. To combat this, Mexico's Ministry of the Interior published a guide on how to reduce the use of sexist language.[58]

German speakers have has also raised questions about how sexism intersects with grammar.[59]

Anthropological linguistics and gender-specific language

Unlike the Indo-European languages, gender-specific pronouns in many other languages are a relatively recent phenomenon (occurring during the early 20th century). Cultural revolution resulted from colonialism in many parts of the world, with attempts to modernize and westernize local languages with gender-specific and animate-inanimate pronouns. As a result, gender-neutral pronouns became gender-specific (see, for example, gender-neutrality in languages without grammatical gender: Turkish).

Gender-specific pejorative terms

Gender-specific pejorative terms intimidate or harm another person because of their gender. Sexism can be expressed in language with negative gender-oriented implications,[60] such as condescension. Other examples include obscene language. Some words are offensive to transgender people, including "tranny", "she-male", or "he-she". Intentional misgendering (assigning the wrong gender to someone) and the pronoun "it" are also considered pejorative.[61][62]

Occupational sexism

Occupational sexism refers to discriminatory practices, statements or actions, based on a person's sex, occurring in the workplace. One form of occupational sexism is wage discrimination.

In 2008 the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) found that while female employment rates have expanded and gender employment and wage gaps have narrowed nearly everywhere, on average women still have 20% less chance to have a job and are paid 17% less than men.[63] The report stated:

[In] many countries, labour market discrimination – i.e. the unequal treatment of equally productive individuals only because they belong to a specific group – is still a crucial factor inflating disparities in employment and the quality of job opportunities [...] Evidence presented in this edition of the Employment Outlook suggests that about 8% of the variation in gender employment gaps and 30% of the variation in gender wage gaps across OECD countries can be explained by discriminatory practices in the labour market.[63][64]

It also found that despite the fact that almost all OECD countries, including the U.S.,[65] have established anti-discrimination laws, these laws are difficult to enforce.[63]

Tokenism

Research shows that women who enter predominantly male work groups often “experience the negative consequences of tokenism: performance pressures, social isolation, and role encapsulation”.[66] However, attributing these negative consequences to tokenism itself might camouflage their root cause: sexism, “and its manifestations in higher-status men’s attempts to preserve their advantage in the workplace”.[67] Furthermore, there has been no causal link proven between the number of women working in an organization/company and the improvement of their conditions of employment (even worse, having an increasing number of women in a work place without appropriately addressing the “sexist attitudes imbedded in male-dominated organizations, may exacerbate women’s occupational problems”).[68]

Wage gap

Several studies have found that women earn a smaller average wage than men. Many economists and feminist scholars have argued that this is the result of systemic gender-based discrimination in the workplace. Others, however, maintain that the wage gap is a result of differences between the choices that men and women make in the workplace, such as more women than men choosing to be full-time parents or work fewer hours to be part-time parents.

Eurostat found a persistent, average gender pay gap of 17.5 percent in the 27 EU member states in 2008.[69] Similarly, the OECD found that female full-time employees earned 17 percent less than their male counterparts in OECD countries in 2009.[63][64]

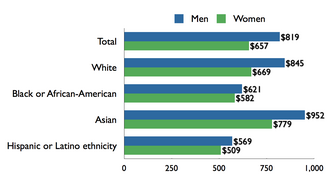

In the United States, the female-to-male earnings ratio was 0.77 in 2009; female full-time, year-round (FTYR) workers earned 77 percent as much as male FTYR workers. Women's earnings relative to men's fell from 1960 to 1980 (60.7 percent to 60.2 percent), rose rapidly from 1980 to 1990 (60.2 to 71.6 percent), leveled off from 1990 to 2000 (71.6 to 73.7 percent) and rose from 2000 to 2009 (73.7 to 77.0 percent).[70][71] When the first Equal Pay Act was passed in 1963, female full-time workers earned 58.9 percent as much as male full-time workers.[70] Research conducted in the Czech and Slovak Republics shows that, even after the governments have passed anti-discrimination legislation, two thirds of the gender gap in wages remained unexplained and segregation continued to “represent a major source of the gap”.[72] The gender gap can also vary across-occupation and within occupation. In Taiwan, for example, studies show how the bulk of gender wage discrepancies occur within-occupation.[73] In Russia, research shows that the gender wage gap is distributed unevenly across income levels, and that it mainly occurs at the lower end of income distribution.[74] Interestingly though, the research also finds that “wage arrears and payment in-kind attenuated wage discrimination, particularly amongst the lowest paid workers, suggesting that Russian enterprise managers assigned lowest importance to equity considerations when allocating these forms of payment”.[75]

The gender pay gap has been attributed to differences in personal and workplace characteristics between women and men (such as education, hours worked and occupation), innate behavioral and biological differences between men and women and discrimination in the labor market (such as gender stereotypes and customer and employer bias). Women interrupt their careers to take on child-rearing responsibilities more frequently than men.[76] In Korea, for example, it has been a long-established practice to lay-off female employers upon marriage.[77] A study by professor Linda Babcock in her book Women Don't Ask shows that men are eight times more likely to ask for a pay raise, suggesting that pay inequality may be partly a result of behavioral differences between the sexes.[78] However, studies generally find that a portion of the gender pay gap remains unexplained after accounting for factors assumed to influence earnings; the unexplained portion of the wage gap is attributed to gender discrimination.[79] Estimates of the discriminatory component of the gender pay gap vary. The OECD estimated that approximately 30% of the gender pay gap across OECD countries is due to discrimination.[63] Australian research shows that discrimination accounts for approximately 60 percent of the wage differential between women and men.[80][81] Studies examining the gender pay gap in the United States show that a large portion of the wage differential remains unexplained, after controlling for factors affecting pay. One study of college graduates found that the portion of the pay gap unexplained after all other factors are taken into account is five percent one year after graduating and twelve percent a decade after graduation.[82][83][84][85] A study by the American Association of University Women (AAUW) found that women graduates are paid less than men doing the same work and majoring in the same field.[86]

Wage discrimination is theorized as contradicting the economic concept of supply and demand, which states that if a good or service (in this case, labor) is in demand and has value it will find its price in the market. If a worker offered equal value for less pay, supply and demand would indicate a greater demand for lower-paid workers. If a business hired lower-wage workers for the same work, it would lower its costs and enjoy a competitive advantage. According to supply and demand, if women offered equal value demand (and wages) should rise since they offer a better price (lower wages) for their service than men do.[88]

Research at Cornell University and elsewhere indicates that mothers are less likely to be hired than equally-qualified fathers and, if hired, receive a lower salary than male applicants with children.[89][90][91][92][93][94] The OECD found that "a significant impact of children on women’s pay is generally found in the United Kingdom and the United States".[40] Fathers earn $7,500 more, on average, than men without children do.[95]

Possible causes for wage discrimination

According to Denise Venable at the National Center for Policy Analysis, the "wage gap" is not the result of discrimination but of differences in lifestyle choices. Venable's report found that women are less likely than men to sacrifice personal happiness for increases in income or to choose full-time work. She found that among adults working between one and thirty-five hours a week and part-time workers who have never been married, women earn more than men. Venable also found that among people aged 27 to 33 who have never had a child, women's earnings approach 98% of men's and "women who hold positions and have skills and experience similar to those of men face wage disparities of less than 10 percent, and many are within a couple of points".[96] Venable concluded that women and men with equal skills and opportunities in the same positions face little or no wage discrimination: "Claims of unequal pay almost always involve comparing apples and oranges".

There is considerable agreement that gender wage discrimination exists, however, when it comes to estimating its magnitude, significant discrepancies are visible. A meta-regression analysis concludes that "the estimated gender gap has been steadily declining" and that the wage rate calculation is proven to be crucial in estimating the wage gap.[97] The analysis further notes that excluding experience and failing to correct for selection bias from analysis might also bring to incorrect conclusions.

Glass ceiling effect

“The popular notion of glass ceiling effects implies that gender (or other) disadvantages are stronger at the top of the hierarchy than at lower levels and that these disadvantages become worse later in a person's career.”[98]

In the United States, women account for 47 percent of the overall labor force, and yet they make up only 6 per-cent of corporate CEOs and top executives.[99] Some researchers see the root cause of this situation in the tacit discrimination based on gender, conducted by current top executives and corporate directors (primarily male), as well as “the historic absence of women in top positions”, which “may lead to hysteresis, preventing women from accessing powerful, male-dominated professional networks, or same-sex mentors”.[100] The glass ceiling effect is noted as being especially persistent for women of colour (according to a report, “women of colour perceive a ‘concrete ceiling’ and not simply a glass ceiling).[101]

In the economics profession, it has been observed (Singell et all, 1996) that women are more inclined than men to dedicate their time to teaching and service. Since continuous research work is crucial for promotion, “the cumulative effect of small, contemporaneous differences in research orientation could generate the observed significant gender difference in promotion”.[102] In the high-tech industry, research shows that, regardless of the intra-firm changes, “extra-organizational pressures will likely contribute to continued gender stratification as firms upgrade, leading to the potential masculinization of skilled high-tech work”.[103]

The United Nations asserts that "progress in bringing women into leadership and decision making positions around the world remains far too slow."[104]

Potential remedies

One research suggests that a possible remedy to the glass ceiling could be increasing the number of women on corporate boards, which could subsequently lead to increases in the number of women working in top management positions.[99] The same research suggests that this could also result in a “feedback cycle in which the presence of more female managers increases the qualified pool of potential female board members (for the companies they manage, as well as other companies), leading to greater female board membership and then further increases in female executives”.[105]

Objectification

Objectification is treating a person, usually a woman, as an object.[106] By being objectified, a person is denied agency.[107] Sexual objectification is where a person is viewed primarily in terms of sexual appeal or as a source of sexual gratification. This is sometimes regarded as a form of sexism.[108] Nussbaum[109] has identified the seven features of treating a human as an object as the following:

1. instrumentality: treating the object as a tool for the objectifier’s purposes

2. denial of autonomy: treating the object as lacking in autonomy and self-determination-

3. inertness: - treating the object as lacking in agency

4. fungibility: - treating the object as interchangeable with other objects

5. violability: - treating the object as lacking in boundaries-integrity

6. ownership: - treating the object as something that is owned by another (can be bought or sold);

7. denial of subjectivity: treating the object as something whose experiences and feelings (if any) need not be taken into account.

According to objectification theory (Fredrickson & Robert, 1997) objectification can have important repercussions on women, particularly young women, as it can lead to mental disorders (depression, eating disorders, etc.).[110]

Objectification can take place in a variety of areas, such as in advertising and pornography.

In advertising

While advertising used to portray women in obvious stereotypical ways (e.g. as a housewife), women in today’s advertisements women are no longer solely confined to the house. However, advertising today nonetheless still stereotypes women, albeit in more subtle ways, including by sexually objectifying them.[111] This is problematic because there appears to be a relationship between the manner in which women are portrayed in advertising and people’s ideas about the role of women in society.[111] Research has shown that gender role stereotyping in advertising is linked to negative attitudes towards women, as well as more acceptance of sexual aggression against women and rape myth acceptance.[111] Furthermore, gender role sterereotyping in advertisements may be injurious to women, as it is linked to negative body image and the development of eating disorders.

Traditionally, in Western countries, advertising was regulated under "obscenity" laws. These dealt with nudity and "indecent" poses, not with objectification itself.

Today, some countries (for example Norway and Denmark) have laws against sexual objectification in advertising.[112] Nudity is not banned, and nude people can be used to advertise a product if they are relevant to the product advertised. Sol Olving, head of Norway's Kreativt Forum (an association of the country's top advertising agencies) explained, "You could have a naked person advertising shower gel or a cream, but not a woman in a bikini draped across a car".[112]

Other countries continue to ban nudity (on traditional obscenity grounds), but also make explicit reference to sexual objectification, such as Israel's ban of bilboards that "depicts sexual humiliation or abasement, or presents a human being as an object available for sexual use". (Art 214)[113]

Pornography

Anti-pornography feminist Catharine MacKinnon argues that pornography contributes to sexism by objectifying women and portraying them in submissive roles.[114] MacKinnon, along with Andrea Dworkin, argues that pornography reduces women to mere tools, and is a form of sex discrimination.[115] The scholars highlight the link between objectification and pornography by stating:

"We define pornography as the graphic sexually explicit subordination of women through pictures and words that also includes (i) women are presented dehumanized as sexual objects, things, or commodities; or (ii) women are presented as sexual objects who enjoy humiliation or pain; or (iii) women are presented as sexual objects experiencing sexual pleasure in rape, incest or other sexual assault; or (iv) women are presented as sexual objects tied up, cut up or mutilated or bruised or physically hurt; or (v) women are presented in postures or positions of sexual submission, servility, or display; or (vi) women's body parts—including but not limited to vaginas, breasts, or buttocks — are exhibited such that women are reduced to those parts; or (vii) women are presented being penetrated by objects or animals; or (viii) women are presented in scenarios of degradation, humiliation, injury, torture, shown as filthy or inferior, bleeding, bruised, or hurt in a context that makes these conditions sexual."[116] Robin Morgan and Catharine MacKinnon suggest that certain types of pornography also contribute to violence against women by eroticizing scenes in which women are dominated, coerced, humiliated or sexually assaulted.[117][118]

Some people opposed to pornography, including MacKinnon, charge that the production of pornography entails physical, psychological and economic coercion of the women who perform and model in it.[119][120][121] Opponents of pornography charge that it presents a distorted image of sexual relations and reinforces sexual myths; it shows women as continually available and willing to engage in sex at any time, with any men, on their terms, responding positively to any requests. They write:

Pornography affects people's belief in rape myths. So for example if a woman says "I didn't consent" and people have been viewing pornography, they believe rape myths and believe the woman did consent no matter what she said. That when she said no, she meant yes. When she said she didn't want to, that meant more beer. When she said she would prefer to go home, that means she's a lesbian who needs to be given a good corrective experience. Pornography promotes these rape myths and desensitises people to violence against women so that you need more violence to become sexually aroused if you're a pornography consumer. This is very well documented.[122]

Defenders of pornography and anti-censorship activists (including sex-positive feminists) argue that pornography does not seriously impact a mentally healthy individual, since the viewer can distinguish between pornography and reality.[123] They contend that both sexes are objectified in pornography (particularly sadistic or masochistic pornography, in which men are objectified and sexually used by women).[124]

Prostitution

Some people argue that prostitution is a form of exploitation of women, which is the result of discrimination of women (a lack of professional opportunities for women, poverty) and of patriarchal views on sexuality which stipulate that unwanted sex with a woman is acceptable, that men's desires must be satisfied at any cost, and that women exist to serve men sexually. They argue that the consent of the prostitute is seriously undermined by direct (pimps) or indirect (social circumstances) coercion.[125][126][127][128][129][130] The European Women's Lobby condemned prostitution as "an intolerable form of male violence".[131]

Carole Pateman writes that:[132]

- "Prostitution is the use of a woman's body by a man for his own satisfaction. There is no desire or satisfaction on the part of the prostitute. Prostitution is not mutual, pleasurable exchange of the use of bodies, but the unilateral use of a woman's body by a man in exchange for money".

Media portrayals

Some feminist scholars believe that media portrayals of demographic groups can both maintain and disrupt attitudes and behaviors toward those groups.[133][page needed][134][135][page needed] These images are often harmful, particularly to women and racial and ethnic minority groups. For example, a study of African American women found they feel that media portrayals of African American women often reinforce stereotypes of this group as overly sexual and idealize images of lighter-skinned, thinner African American women (images African American women describe as objectifying).[136] In a recent analysis of images of Haitian women in the Associated Press photo archive from 1994 to 2009, several themes emerged emphasizing the "otherness" of Haitian women and characterizing them as victims in need of rescue.[137]

Sexist jokes

Sexist jokes can be a form of sexual objectification, which reduces the subject of the joke to an object (e.g., "What do you do when your dishwasher won't work?" Answer: "You hit her"). They not only objectify women or men, but can also condone violence or prejudice against men or women.[citation needed] "Sexist humor—the denigration of women through humor—for instance, trivializes sex discrimination under the veil of benign amusement, thus precluding challenges or opposition that nonhumorous sexist communication would likely incur."[138] A study of 73 male undergraduate students by Ford (2007) found that "sexist humor can promote the behavioral expression of prejudice against women amongst sexist men".[138] According to the study, when sexism is presented in a humorous manner it is viewed as tolerable and socially acceptable. "Disparagement of women through humor 'freed' sexist participants from having to conform to the more general and more restrictive norms regarding discrimination against women."[138]

Gender discrimination

Gender discrimination is discrimination on the basis of actual or perceived gender identity. “Gender identity” is defined to mean “the gender-related identity, appearance, or mannerisms or other gender-related characteristics of an individual, with or without regard to the individual’s designated sex at birth”.[139] Gender discrimination is theoretically different from sexism.[140] Whereas, sexism is prejudice based on biological sex, gender discrimination specifically addresses discrimination towards identity based orientations, including third gender, genderqueer, and other non-binary identified people.[141] Banning discrimination on the basis of gender identity and expression has emerged as a subject of contestation in the American legal system.[142] Legal interpretation of “sex” under Title VII of the United States’ Employment Non Discrimination Act (ENDA; H.R. 1755/S. 815) has, since the ruling of Price Waterhouse, encompassed both gender and sex. Since first introduced in Congress since 1993 at the 103rd Congress, the Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), has taken different stances on the inclusion of gender discrimination under the term “sex”.[139] More recently, the stated purpose of the legislation is “to address the history and persistent, widespread pattern of discrimination, including unconstitutional discrimination, on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity by private sector employers and local, State, and Federal Government employers,” as well as to provide effective remedies for such discrimination. However, under current law Title VII does not expressly prohibit discrimination based on gender identity or transsexualism.[139] The myriad forms of discrimination associated with gender non-conformity are therefore not expressly addressed nor protected under the ENDA. According to a recent report by the Congressional Research Service, “although the majority of federal courts to consider the issue have concluded that discrimination on the basis of gender identity is not sex discrimination, there have been several courts that have reached the opposite conclusion in the years since the Supreme Court's decision in Price Waterhouse”.[139] Hurst states, “Courts often confuse sex, gender and sexual orientation, and confuse them in a way that results in denying the rights not only of gays and lesbians, but also of those who do not present themselves or act in a manner traditionally expected of their sex”.[143] Scholars have suggested amending the EDNA to include these gender orientations. However, counter arguments question whether Title VII is general enough to include sexual orientation or gender identity discrimination in legal claims.[142] Gender discrimination is therefore, a gender identity based discrimination, whose codification into American and other legal systems has remained contested.

Transgender discrimination

Transgender discrimination is discrimination towards peoples whose gender identity differs from the social expectations of the biological sex they were born with.[144] Forms of discrimination include but are not limited to identity documents not reflecting one’s gender, sex-segregated public restrooms and other facilities, dress codes according to binary gender codes, and lack of access to and existence of appropriate health care services.[145] In a recent adjudication, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) concluded that discrimination against a transgendered individual is sex discrimination.[145] The National Transgender Discrimination Survey, the most extensive survey of transgender discrimination, in collaboration with the National Black Justice Coalition recently showed that Black transgender people in the United States suffer “the combination of anti-transgender bias and persistent, structural and individual racism” and that “black transgender people live in extreme poverty that is more than twice the rate for transgender people of all races (15%), four times the general Black population rate 9% and over eight times the general US population rate (4%)”.[146] In another study conducted in collaboration with the League of United Latin American Citizens, Latino/a transgender people who were non-citizens were most vulnerable to harassment, abuse and violence.[147] Peoples of color subjected to transgender discrimination suffer intersecting structural and individual levels of discrimination.

Gender discrimination in politics

Gender has been used, at times, as a tool of discrimination against women in the political sphere. Indeed, Women's suffrage was not achieved until 1893, when New Zealand was the first country to grant women the right to vote. Saudi Arabia was the last country to grant women the right to vote in 2011.[148] Some Western countries allowed women the right to vote only relatively recently: Swiss women gained the right to vote in federal elections in 1971,[149] and Appenzell Innerrhoden became the last canton to grant women the right to vote on local issues (in 1991, when it was forced to do so by the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland).[150] French women were granted the right to vote in 1944.[151][152] In Greece, women obtained the right to vote in 1952.[153]

While almost every woman today has the right to vote, there is still progress to be made for women in politics. Indeed, studies have shown that in several democracies including Australia, Canada and the United States, women are still represented using deep-rooted gender stereotypes in the press [154] In fact, multiple authors have shown that gender differences in the media are less evident today than they used to be in the 1980s, but are nonetheless still present. Certain issues (e.g. education) are likely to be linked with female candidates, while other issues (e.g. taxes) are likely to be linked with male candidates.[154] In addition, there is more emphasis on female candidates’ personal qualities, such as their appearance and their personality, as females are portrayed as “emotional” and “dependent”.[154] This is problematic because voters’ views of the female and male candidates may be affected, as well as their views of women’s role in the political sphere [154]

Examples

Sexism takes a number of forms, and is sometimes subtle or unconscious.

Child marriage

A child marriage is a marriage where one or both spouses are under 18.[155][156] Girls are disproportionately the most affected.[155] Child marriages are most common in South Asia, the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa, but occur in other parts of the world, too. The practice of marrying young girls is rooted in patriarchal ideologies of control of female behavior, and is also sustained by traditional practices such as dowry and bride price. Child marriage is strongly connected with the protection of female virginity.[157] UNICEF states that:[155]

- "Marrying girls under 18 years old is rooted in gender discrimination, encouraging premature and continuous child bearing and giving preference to boys' education. Child marriage is also a strategy for economic survival as families marry off their daughters at an early age to reduce their economic burden."

Consequences of child marriage include restricted education and employment prospects, increased risk of domestic violence, child sexual abuse, pregnancy and birth complications, social isolation.[156][157] Early and forced marriage are defined as forms of modern-day slavery by the International Labour Organisation.[158]

According to the UN, the ten countries with the highest rates of child marriage are: Niger (75%), Chad and Central African Republic (68%), Bangladesh (66%), Guinea, Mozambique, Mali, Burkina Faso, South Sudan, and Malawi.[159]

Controlling women's dressing attire

Laws that dictate how women must dress are seen by many international human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, as a form of gender discrimination.[160] Amnesty International states that:[160]

- "Interpretations of religion, culture or tradition cannot justify imposing rules about dress on those who choose to dress differently. States should take measures to protect individuals from being coerced to dress in specific ways by family members, community or religious groups or leaders."

In many places, women who do not dress in socially and legally proscribed ways are often subjected to violence (for instance by the authorities, such as the religious police, by family members, or by the community).[161][162]

Criminal justice

The examples and perspective in this section may not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (September 2013) |

Some studies in the United States have shown that for identical crimes, men are given harsher sentences than women. Controlling for arrest offense, criminal history and other pre-charge variables, sentences are over 60 percent heavier for men. Women are more likely to avoid charges entirely, and to avoid imprisonment if convicted.[163][164] The gender disparity varies according to the nature of the case (for example, there is a smaller gender gap in fraud cases than in drug trafficking and firearms). This disparity occurs in U.S. federal courts, despite guidelines designed to avoid differential sentencing.[165]

There are many reasons postulated for the gender disparity. One of the most common is the larger caregiving role of women.[163][164][165] Other possible reasons include the "girlfriend theory" (whereby women are seen as tools of their boyfriends),[164] the theory that female defendants are more likely to cooperate with authorities,[164] and that women are often successful at turning their violent crime into victimhood by citing defenses such as postpartum depression and battered wife syndrome.[166] However, none of these theories can account for the total disparity,[164] and sexism has also been suggested as an underlying cause.[167]

Transgender people are consistently discriminated against in jails and prisons. They are almost always put in the jail based on their sex and not their gender identity and are denied the ability to be able to take hormones or get sexual reassignment surgery and if they do they are never moved to prisons of the other gender. Studies show that trans people face an enormous amount of harassment and are at higher risk for sexual assault when they are not placed in prisons that match their gender identity.[168]

Domestic violence

Domestic violence takes a number of forms (including verbal, physical and psychological abuse), which vary across the gender spectrum. Domestic violence is tolerated and even legally accepted in many parts of the world. For instance, in 2010, the United Arab Emirates (UAE)'s Supreme Court ruled that a man has the right to physically discipline his wife and children if he does not leave physical marks.[169]

According to a report of the Special Rapporteur submitted to the 58th session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights (2002) concerning cultural practices in the family that reflect violence against women (E/CN.4/2002/83):

The Special Rapporteur indicated that there had been contradictory decisions with regard to the honour defense in Brazil, and that legislative provisions allowing for partial or complete defense in that context could be found in the penal codes of Argentina, Ecuador, Egypt, Guatemala, Iran, Israel, Jordan, Peru, Syria, Venezuela and the Palestinian National Authority.[170]

Honor killings are a form of domestic violence which continues to be practiced in several parts of the world. The victims of honor killings are usually women.[171] Victims of honor killings are killed for reasons such as refusing to enter an arranged marriage, being in a relationship that is disapproved by their relatives, having sex outside marriage, becoming the victim of rape, dressing in ways which are deemed inappropriate, or engaging in homosexual relations.[172][173][174]

Stoning (a form of punishment in which a group throws stones at a person, usually until the victimn dies) is associated with domestic disputes, especially those involving accusations of loss of chastity, adultery or the refusal of an arranged marriage.[citation needed] Recently, several people have been sentenced to death by stoning after being accused of adultery in Iran, Somalia, Afghanistan, Sudan, Mali and Pakistan.[175][176][177][178][179][180][181][182][183]

Practices such as honor killings and stoning continue to be supported by mainstream politicians and other officials in some countries. In Pakistan, after the 2008 Balochistan honour killings in which five women were killed by tribesmen of the Umrani Tribe of Balochistan, Pakistani Federal Minister for Postal Services Israr Ullah Zehri defended the practice:[184] "These are centuries-old traditions, and I will continue to defend them. Only those who indulge in immoral acts should be afraid."[185] Following the 2006 case of Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani (which has placed Iran under international pressure for its stoning sentences), Mohammad-Javad Larijani (a senior envoy and chief of Iran’s Human Rights Council) defended the practice of stoning; he claimed it was a "lesser punishment" than execution, because it allowed those convicted a chance at survival.[186]

Education

The third Millennium Development Goal is directed at achieving gender equality and women’s empowerment around the world.[187] Improvement of equal educational opportunity contributes to the women’s empowerment[188] Women have traditionally had limited access to higher education.[189] When women were admitted to higher education, they were encouraged to major in less-intellectual subjects; the study of English literature in American and British colleges and universities was instituted as a field considered suitable to women's "lesser intellects".[190]

Educational specialties in higher education produce and perpetuate the existing segregation between men and women. Disparity persists particularly in computer and information science, where women receive only 21 percent of the undergraduate degrees, and in engineering, women obtain only 19 percent of the degrees in 2008.[191]

World literacy is lower for females than for males. Latest data from CIA World Factbook shows that 79.7% of women are literate, compared to 88.6% of men (aged 15 and over).[192] In some parts of the world, girls continue to be excluded from proper public or private education. In parts of Afghanistan, girls who go to school face serious violence from some local community members and religious groups.[193][193] According to 2010 UN estimates, only Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen had less than 90 girls per 100 boys at school.[194] Greater variation of gender educational discrepancy exists within countries. The situation appears to be more critical in rural areas, for instance UNICEF statistics revealed that in Nigerian villages less than 40 girls per 100 boys gained access to primary education.[195] Studies of Sri Lanka economic development suggested that increased life expectancy of girls encourages educational investment because a longer time horizon increases the value of investments that pay out over time.[196]

Girls' educational opportunities and results have greatly improved in the West. Since 1991, the proportion of women enrolled in college in the United States has exceeded the enrollment rate for men; the gap has widened over time.[197] As of 2007, women made up the majority—54 percent—of the 10.8 million college students enrolled in the United States.[198]

Research has found that discrimination continues; boys receive more attention, praise, blame and punishment in the grammar-school classroom,[199] and "this pattern of more active teacher attention directed at male students continues at the postsecondary level".[200] Over time, female students speak less in a classroom setting.[201]

It is also argued that the educational system has become "feminized", allowing girls more of a chance at success with a more "girl-friendly" environment in the classroom;[202] this is seen to hinder boys by punishing "masculine" behaviour and diagnosing boys with behavioural disorders.[203]

In 2011 a United States Bureau of Labor Statistics report found that women are more likely than men to earn a bachelor's degree by age 23.[204][205] A survey conducted by the Council of Graduate Schools similarly found that in the 2008–09 school year, women earned 50.9% of doctorates and 60% of master's degrees.[206] However, only one-fifth of physics Ph.D.’s in the US are awarded to women, and only about half of those women are American; of all the physics professors in the country, only 14 percent are women.[207]

There is a clear evidence that education plays an important role in determining women's input in financial and household decisions related to social and organizational matters.[208]

Girls earn higher grades than boys until the end of high school; in some districts, girls achieve higher marks despite similar (or lower) scores than boys on standardised tests.[209]

Fashion

Feminists argue that some fashion trends have been oppressive to women; they restrict women's movements, increase their vulnerability and endanger their health.[210] The fashion industry is dealing with a great deal of criticism, as their association of thin-models and beauty has said to encourage bulimia and anorexia nervosa within women, as well as locking female consumers into false feminine identities.[211]

The assigning of gender specific baby clothes from young ages is seen as sexist by some as it can instil in children from young ages a belief in strong gender stereotypes.[212] An example of this is the assignment in some countries of the color pink to girls and blue to boys. This fashion, however, is a recent one; at the beginning of the 20th century the trend was the opposite: blue for girls and pink for boys. In the early 1900s, The Women's Journal wrote: "That pink being a more decided and stronger colour, is more suitable for the boy, while blue, which is more delicate and dainty, is prettier for the girl." DressMaker magazine also explained: "The preferred colour to dress young boys in is pink. Blue is reserved for girls as it is considered paler, and the more dainty of the two colours, and pink is thought to be stronger (akin to red)."[213]

.

Today, in most countries of the world, it is considered inappropriate for boys to wear dresses and skirts, but this, again, is a modern worldview: for example, from the mid-16th century[214] until the late 19th or early 20th century, young boys in the Western world were unbreeched and wore gowns or dresses until an age that varied between two and eight.[215] Also, throughout much of the history, in most cultures, men have worn skirt like clothes and worn long hair. In many parts of the world, such as much of sub-Saharan Africa, it is considered normal for women to wear very short hair, with the hairstyles of boys being the same to those of girls.

Female infanticide and sex-selective abortion

Female infanticide is the killing of very young female children. It is an extreme form of gender based violence.[216][217][218] Female infanticide is more common than male infanticide, and is especially prevalent in parts of Asia, such as parts of India and China.[217][219][220] Recent studies suggest that over 90 million girls and women are missing in China and India as a result of systematic sex discrimination.[221][222]

Sex-selective abortion involves terminating a pregnancy based upon the predicted gender of the baby. The abortion of female fetuses is most common in areas where the culture values male children over females,[223] such as parts of the People's Republic of China, India, Pakistan, Korea, Taiwan, and the Caucasus.[223][224] One reason for this preference is that males are seen as generating more income than females. A 2011 report on Science Daily stated that the trend grew steadily during the previous decade, and would probably cause a future shortage of women.[225]

Forced sterilization and forced abortion

Forced sterilization and forced abortion are forms of gender-based violence.[216]

Forced sterilization was practiced during the first half of the 20th century by many Western countries (including the US) and there are reports of this practice being currently employed in some countries, such as Uzbekistan and China.[226][227][228][229]

Forced abortions are today associated mostly with China. Although they are not an official policy of the country, they result from government pressure on local officials who, in turn, employ strong-arm tactics on pregnant mothers. In 2012, a highy publicized case of a forced abortion involving the photo of the fetus has sparked international outrage.[230]

Female genital mutilation

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision, is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as "all procedures that involve partial or total removal of the external female genitalia, or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons". WHO states that, "The procedure has no health benefits for girls and women" and "Procedures can cause severe bleeding and problems urinating, and later cysts, infections, infertility as well as complications in childbirth increased risk of newborn death"[231] and "FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of the human rights of girls and women. It reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes, and constitutes an extreme form of discrimination against women".[231] Feminist activist Seham Abd el Salam writes that FGM campaigners have been criticized by women's studies groups for their lack of recognition of male circumcision as a form of genital mutilation.[232]

According to a 2013 UNICEF report, 125 million women and girls in Africa and the Middle East have experienced FGM.[233] The highest prevalence in Africa is documented in Somalia (98 percent of women affected), Guinea (96 percent), Djibouti (93 percent), Egypt (91 percent), Eritrea (89 percent), Mali (89 percent), Sierra Leone (88 percent), Sudan (88 percent), Gambia (76 percent), Burkina Faso (76 percent), Ethiopia (74 percent), Mauritania (69 percent), Liberia (66 percent), and Guinea-Bissau (50 percent).[233]

Hate-motivated sexual assault

Rape and sexual assault are considered to be acts of hate. Their relationship to sexism is the frequent desire on the part of the perpetrator for power over the victim. The Center for Women Policy Studies stated that "victims almost always are chosen for what they are rather than who they are"; a woman is more likely to be attacked because of her gender than her individuality.[234]

Research into factors motivating perpetrators of rape against women frequently reveals a pattern of hatred towards women and pleasure in inflicting psychological and physical trauma, rather than sexual interest.[235] Mary Odem posits that rape is the result not of pathology but of systems of male dominance, cultural practices and beliefs which objectify and degrade women.[236]

Mary Odem, Jody Clay-Warner and Susan Brownmiller consider that sexist attitudes are propagated by a series of myths about rape and rapists.[236]: 130–140 [237] They state that in contrast to those myths, rapists often plan a rape before they choose a victim[236] and acquaintance rape (not assault by a stranger) is the most common form of rape.[236]: xiv [238] Odem also asserts that these rape myths propagate sexist attitudes about men, by perpetuating the belief that men cannot control their sexuality.[236]

In response to acquaintance rape, the "Men Can Stop Rape" movement has been implemented.[239] The U.S. military has begun a similar movement, with the slogan "My strength is for defending".[240]

In Yes Means Yes: Visions of Female Sexual Power and A World Without Rape by Jaclyn Friedman and Jessica Valenti, it is argued that in the US rape is most often popularly depicted (in the media, in public discourse, in movies etc.) as stranger-rape (with a stereotypical stranger who "jumps out of the bushes"), despite the fact that most rapes do not fit this stereotype. In presenting rape in this way to the public, patriarchal society ensures that women are kept under control, at home/indoors, living their life according to traditional gender roles and expectations, dressed 'modestly'. This leads to an ideology that women are safe at home (ignoring rape by family members/partners), and to blaming of victims.[241]

Military service

Military service has been considered a gender-specific duty. Some countries, such as Israel, require military service regardless of gender. Others (such as Turkey and Singapore) still use a system of conscription which only requires military service for men, although women are permitted to serve voluntarily.

In the United States, all men must register with the Selective Service System within 30 days of their 18th birthday.[242] The system does not require women to register, leading to criticism that it discriminates against men by forcing them into a dangerous role based on gender.[243]

Misandry

Misandry is the hatred of men and boys as a societal group or as individuals.

Misogyny

Misogyny is the hatred of women and girls as a societal group or as individuals.

Sexual slavery

Sexual slavery occurs when people are coerced into slavery for sexual exploitation. The incidence of sexual slavery by country has been studied and tabulated by UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) with the cooperation of a number of international agencies.[244] Sexual slavery also includes single-owner slavery, the ritual slavery associated with certain religious practices, slavery for primarily non-sexual purposes where non-consensual sex is common and forced prostitution.

Transphobia

Transphobia refers to prejudice against transsexuality and transsexual (or transgender) people based on their gender identification. Whether intentional or not, transphobia can have negative consequences for the object of the negative attitude. The lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) movement opposes sexism against transsexuals. One form of sexism against transsexuals is "women-only" and "men-only" events and organizations, which have been criticized for excluding trans women and trans men.[245][246]

Treatment of victims of rape

Stigmatization of women and girls who have been raped is widespread in many cultures; is a result of gender inequality and patriarchal social norms; and affects the ability of victims to recover.[247][248] In many parts of the world, women who have been raped are ostracized, rejected by their families, subjected to violence - in extreme cases to honor killings, because they are deemed to have brought 'shame' on their families.[247][249]

There is also a strong connection between rape and forced marriage, through practices such as forcing of a woman or girl who has been raped to marry her rapist, in order to restore the 'honor' of her family;[247][250] or marriage by abduction, a practice in which a man abducts the woman or girl whom he wishes to marry and rapes her, in order to force the marriage (this practice is very common in Ethiopia[251][252][253]). The criminalization of marital rape (forcing one's own spouse to have sex) is very recent, having occurred during the past few decades; and in many countries it is still legal. Several countries in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia made spousal rape illegal before 1970; other countries in Western Europe and the English-speaking Western World outlawed it later, mostly in the 1980s and 1990s.[254] In some parts of the world the lack of criminalization of marital rape coupled with the practice of child marriage leads to serious forms of child sexual abuse being legitimized. The WHO wrote that: "Marriage is often used to legitimize a range of forms of sexual violence against women. The custom of marrying off young children, particularly girls, is found in many parts of the world. This practice – legal in many countries – is a form of sexual violence, since the children involved are unable to give or withhold their consent".[247] (see above the section on Child Marriage).

In countries where fornication or adultery are illegal, victims of rape can be charged under this laws (even if the victims succeed in proving their rape case, they can still be charged with a criminal offense if the court finds they were not virgins at the time of the assault - if they were unmarried).[255]

The WHO states that: "Persons who have been raped should receive treatment consistent with the dignity and respect they are owed as human beings."[256]

War rape

War rapes are rapes committed by soldiers, other combatants or civilians during armed conflict, war or military occupation, and are distinguished from in-service sexual assault and rape committed amongst troops.[257][258][259] It also encompasses situations in which women are forced into prostitution or sexual slavery by an occupying power, such as Japanese comfort women during World War II. Sexual violence and rape as a weapon of war also affects a large number of men, although it is less-often reported.[260] The war-torn Democratic Republic of the Congo has been described as the "rape capital of the world" with more than 400,000 rapes reported in just one year.[261]

Antisexism movements

In Ecuador, the Pink Helmets (Cascos Rosas), created in May 2011 by 18-year-olds Freddy Caleron and Damian Valencia, sought to unite young men against machismo.[262] The Pink Helmets published a manual with suggestions to end violence in society, relationships, within families, and among friends. The Pink Helmets' founders and participating members, who call themselves neomasculinos and are 15–20 years old, visit schools and the streets to give talks and participate in festivals (such as the Quito Fest) in collaboration with UN Women (part of the United Nations) to increase awareness of violence and the movement against it.[263] Chauvinism and violence are common in Ecuador, with 40% of children under age 15 saying that they have witnessed acts of violence at home.[citation needed] According to the National Plan for the Eradication of Gender Violence of the Government of Ecuador, 80% of women have been victims of violence at least once and 21% of children and adolescents have been sexually abused[264] (no official data provide a concrete number of women who have been killed or injured by men). The movement aims to promote gender equality, eliminate gender violence against women and encourage a "dialogue of respect between men and women from adolescence without hesitation to criticize sexist concepts that live in their culture".[265]

See also

Bibliography

- Bojarska, Katarzyna (2012). ""Responding to lexical stimuli with gender associations: A Cognitive–Cultural Model"". Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 32: 46. doi:10.1177/0261927X12463008..

- Haberfeld, Yitchak. "Employment Discrimination: An Organizational Model."

- Matsumoto, David. "The Handbook of Culture and Psychology" Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0195131819.

- Reference List: ↑ Feder, Jody and Cynthia Brougher. „Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Discrimination in Employment: A Legal Analysis of the Employment Non_Discrimination Act (ENDA).“ July 15, 2013. Available (online): www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40934.pdf ↑ Macklem, Tony. 2004. Beyond Comparison: Sex and Discrimination. New York: Cambridge Univ. Press. ↑ Atwell, Mary Welek. 2002. Equal Protection of the Law?: Gender and Justice in the United States. New York: P. Lang. ↑ Feder, Jody and Cynthia Brougher. „Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Discrimination in Employment: A Legal Analysis of the Employment Non_Discrimination Act (ENDA).“ July 15, 2013. Available (online): www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R40934.pdf ↑ “Employment Non-Discrimination Act”. Human Rights Campaign. Available (online): http://www.hrc.org/laws-and-legislation/federal-legislation/employment-non-discrimination-act ↑ Hurst, C. Social Inequality: Forms, Causes, and Consequences. Sixth Edition. 2007. 131, 139–142 ↑ “Transgender.” UC Berkekely Online. Available (online): http://geneq.berkeley.edu/lgbt_resources_definiton_of_terms#transgender ↑ “Discrimination against Transgender People.” ACLU. Available (online) : https://www.aclu.org/lgbt-rights/discrimination-against-transgender-people ↑ “Discrimination against Transgender People.” ACLU. Available (online) : https://www.aclu.org/lgbt-rights/discrimination-against-transgender-people ↑ “Discrimination against Transgender People.” ACLU. Available (online) : https://www.aclu.org/lgbt-rights/discrimination-against-transgender-people

- Leila Schneps and Coralie Colmez, Math on trial. How numbers get used and abused in the courtroom, Basic Books, 2013. ISBN 978-0-465-03292-1. (Sixth chapter: "Math error number 6: Simpson's paradox. The Berkeley sex bias case: discrimination detection").

- Management Journal 35.1 (1992): 161-180. Business Source Complete.

- Kail, R., & Cavanaugh, J. (2010). Human Growth and Development (5 ed.). Belmont, Ca: Wadworth Learning.

Notes

Constructs such as ibid., loc. cit. and idem are discouraged by Wikipedia's style guide for footnotes, as they are easily broken. Please improve this article by replacing them with named references (quick guide), or an abbreviated title. (December 2013) |

- ^ "Sexism - Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Merriam-webster.com. August 31, 2012. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ Matsumoto, 2001. P.197.

- ^ Nakdimen KA The American Journal of Psychiatry [1984, 141(4):499-503]

- ^ [Doob, Christopher B. 2013. Social Inequality and Social Stratification in US Society. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc.]

- ^ Macionis, Gerber, John, Linda (2010). Sociology 7th Canadian Ed. Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Inc.. pp. 298.

- ^ [Forcible Rape Institutionalized Sexism in the Criminal Justice System| Gerald D. Robin Division of Criminal Justice, University of New Haven]

- ^ a b c d e f "Feminism Friday: The origins of the word "sexism"". Finallyfeminism101.wordpress.com. October 19, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ Neuwirth, Jessica (2004). "Unequal: A Global Perspective on Women Under the Law". Ms. Magazine.

- ^ Peter N. Stearns (Narrator). A Brief History of the World Course No. 8080 [Audio CD]. The Teaching Company. ASIN B000W595CC.

- ^ Bruce W. Frier and Thomas A.J. McGinn, A Casebook on Roman Family Law (Oxford University Press: American Philological Association, 2004), pp. 31–32, 457, et passim.

- ^ The English translation is from this note to Summers' 1928 introduction.

- ^ Thurston 2001. p. 01.

- ^ largely excluding the Iberian Peninsula and Italy; "Inquisition Spain and Portugal, obsessed with heresy, ignored the witch craze. In Italy, witch trials were comparatively rare and did not involve torture and executions." Anne L. Barstow, Witchcraze : a New History of the European Witch Hunts, HarperCollins, 1995.

- ^ Barstow, Anne Llewellyn (1994) Witchcraze: A New History of the European Witch Hunts San Francisco: Pandora.

- ^ Thurston 2001. pp. 42-45.

- ^ Kramer and Sprenger. Malleus Malificarum.

- ^ http://edition.cnn.com/2011/12/13/world/meast/saudi-arabia-beheading/

- ^ Blackstone, William. Commentaries on the Laws of England.http://www.mdx.ac.uk/WWW/STUDY/xBlack.htm

- ^ "Legacy '98: Detailed Timeline". Legacy98.org. 2001-09-19. Retrieved 2010-11-20.

- ^ http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/explore/cmcf-vsi-women-in-france.pdf

- ^ "France's leading women show the way". Parisvoice.com. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ "Lesson - The French Civil Code (Napoleonic Code) - Teaching Womens Rights From Past to Present". Womeninworldhistory.com. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

{{cite web}}: C1 control character in|title=at position 66 (help) - ^ .http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/06/world/europe/06iht-letter.html?_r=1&pagewanted=all

- ^ http://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.356386.de/dp998.pdf

- ^ "Spain - Social Values And Attitudes". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ http://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/hrc/docs/ngos/Yemen%27s%20darkside-discrimination_Yemen_HRC101.pdf

- ^ http://law.case.edu/saddamtrial/documents/Iraqi_Penal_Code_1969.pdf

- ^ http://www.hrw.org/reports/2002/drc/Congo0602-09.htm

- ^ Manstead, A. S. R.; Hewstone, Miles; et al. The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Mass., USA: Blackwell, 1999, 1995, pp. 256 – 57, ISBN 978-0-631-22774-8.

- ^ Wagner, David G. and Joseph Berger (1997). Gender and Interpersonal Task Behaviors: Status Expectation Accounts. Sociological Perspectives, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 1-32.

- ^ Williams, John E. and Deborah L. Best. Measuring Sex Stereotypes: A Multinational Study. Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1990, ISBN 978-0-8039-3815-1.

- ^ Fiske, Susan T., Amy J. C. Cuddy, Peter Glick, Jun Xu (2002). A Model of (Often Mixed) Stereotype Content: Competence and Warmth Respectively Follow From Perceived Status and Competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol. 82, No. 6, p. 892.

- ^ Thoman, Dustin B., Paul H. White, Niwako Yamawaki, and Hirofumi Koishi. "Variations of Gender–math Stereotype Content Affect Women’s Vulnerability to Stereotype Threat." Sex Roles 58.9-10 (2008): 702-12. Print.

- ^ Fortin, Nicole, "Gender Role Attitudes and the Labour Market Outcomes of Women Across OECD Countries", Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 2005, 21, 416–438.

- ^ Shih, Margaret, Todd L. Pittinsky and Nalini Ambady (1999). Stereotype Susceptibility: Identity, Salience and Shifts in Quantitative Performance. Psychological Science, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 80-3.

- ^ Steele, Claude M. (1997). A Threat Is in the Air: How Stereotypes Shape Intellectual Identity and Performance. American Psychologist, Vol. 52, No. 6, pp. 613-29.

- ^ Correll, Shelley J. (2001). Gender and the career choice process: The role of biased self-assessments. American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 106, Issue 6, pp. 1691-1730.

- ^ Correll, Shelley J. (2004). Constraints into Preferences: Gender, Status, and Emerging Career Aspirations. American Sociological Review, Vol 69, Issue 1, pp. 93-113.

- ^ Susan Rachael SeemM, D. C. (2006). Healthy women, healthy men, and healthy adults: An evaluation of gender role stereotypes in the twenty-first century. Sex Roles, 55(3-4), 247-258. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9077-0

- ^ a b OECD (2002). Emplyoment Outlook, Chapter 2: Women at work: who are they and how are they faring? Paris: OECD 2002.

- ^ Lawn-Day, G.A. and Ballard, S. “Speaking out: Perceptions of women managers in public service.” Review of Public Personnel Administration, Vol. 16 No. 1,1996, pp. 41-58

- ^ Ashraf, J. “Is Gender Pay Discrimination on the Wane? Evidence from Panel Data, 1968-1989”, Industrial and Labor Relations Review, Vol. 49 No.3, 1996, p.539

- ^ "Women Deserve Equal Pay". Now.org. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ "The Gender Pay Gap is a Complete Myth". CBS News. March 8, 2011. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ^ Roehling, Patricia V., Mark V. Roehling, Jeffrey D. Vandlen, Justin Blazek, William C. Guy (2009). Weight discrimination and the glass ceiling effect among top US CEOs. Equal Opportunity International, Vol. 28, Iss. 2, pp.179 - 196, doi:10.1108/02610150910937916.

- ^ Moult, Julie. Women's careers more tied to weight than men -- study. Herald Sun, April 11, 2009.

- ^ Badgett, M.L., Lau, H., Sears, B., & Ho, D. (2007) Bias in the Workplace: Consistent Evidence of Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Discrimination. Los Angeles: The Williams Institute. http://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/research/workplace/bias-in-the-workplace-consistent-evidence-of-sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity-discrimination/

- ^ a b Santa Rosa Junior College. “Uses and Abuses of Language.” http://online.santarosa.edu/presentation/page/?37061

- ^ Linguarama. “Sexism in Language.” http://www.linguarama.com/ps/legal-themed-english/sexism-in-language.htm

- ^ a b Spender, Dale. “Man Made Language.” http://www.marxists.org/reference/subject/philosophy/works/ot/spender.htm

- ^ Mills, Sara. “Language and Sexism.” http://www.langtoninfo.com/web_content/9780521001748_frontmatter.pdf

- ^ Mille, Katherine Wyly and Paul McIlvenny. “Gender and Spoken Interaction: A Survey of Feminist Theories and Sociolinguistic Research in the United States and Britain.” http://paul-server.hum.aau.dk/research/cv/Pubs/mille-mcilvenny.pdf

- ^ Ruthven, K.K. “Feminist literary studies: an introduction.” http://catdir.loc.gov/catdir/samples/cam034/90034404.pdf

- ^ http://www.friesian.com/language.htm

- ^ Sayare, Scott. “’Mademoiselle’ Exits Official France.” http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/23/world/europe/france-drops-mademoiselle-from-official-use.html?_r=0

- ^ Carson, Culley Jane. “Attacking a Legacy of Sexist Grammar in the French Class: A Modest Beginning.” http://www.jstor.org/stable/40545648

- ^ Tan, Dali. “Sexism in the Chinese Language.” http://www.jstor.org/stable/4316075

- ^ BBC. "Mexico advises workers on sexist language." http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-12843948

- ^ Reuters. "Grappling with language sexism." http://blogs.reuters.com/great-debate-uk/2011/03/05/grappling-with-language-sexism/

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Mills College Transgender Best Practices Taskforce & Gender Identity and Expression Sub-Committee of the Diversity and Social Justice Committee. Report on Inclusion of Transgender and Gender Non-Conforming Students Best Practices, Assessment and Recommendations. Oakland, Calif.: Mills College, February 2013, p. 9.

- ^ Anti-transgender Language Commentary: Trans Progressive by Autumn Sandeen San Diego, Calif.: San Diego LGBT Weekly, February 3, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e OECD. OECD Employment Outlook - 2008 Edition Summary in English. OECD, Paris, 2008, p. 3-4.

- ^ a b OECD. OECD Employment Outlook. Chapter 3: The Price of Prejudice: Labour Market Discrimination on the Grounds of Gender and Ethnicity. OECD, Paris, 2008.

- ^ The U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. "Facts About Compensation Discrimination". Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ Janice D. Yoder (1991): Rethinking Tokenism: Looking beyond Numbers. Gender and Society, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Jun., 1991), pp. 178-192 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc.

- ^ Ibid.