Severo Ochoa

Severo Ochoa ForMemRS | |

|---|---|

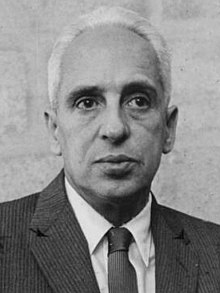

Severo Ochoa in 1958 | |

| Born | Severo Ochoa de Albornoz 24 September 1905 |

| Died | 1 November 1993 (aged 88) |

| Citizenship | Spanish (1905–1956), American (1956–1993) |

| Education | University of Madrid Medical School, University of Glasgow |

| Known for | Discovery of mechanisms in the biological synthesis of RNA and DNA |

| Spouse | Carmen Garcia Cobian[1] |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biochemistry, molecular biology |

| Institutions | Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology, Berlin; National Institute for Medical Research, London; New York University Grossman School of Medicine; Washington University School of Medicine |

| Academic advisors | Pedro Arrupe, Juan Negrín, Otto Meyerhof, Henry Hallett Dale |

Severo Ochoa de Albornoz (Spanish: [seˈβeɾo oˈtʃoa ðe alβoɾˈnoθ]; 24 September 1905 – 1 November 1993) was a Spanish physician and biochemist, and winner of the 1959 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine together with Arthur Kornberg for their discovery of "the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)".[2][3][4][5]

Education and early life

[edit]Ochoa was born in Luarca (Asturias), Spain. His father was Severo Manuel Ochoa (who he was named after), a lawyer and businessman, and his mother was Carmen de Albornoz. Ochoa was the nephew of Álvaro de Albornoz (President of the Second Spanish Republic in exile and former Foreign Minister), and a cousin of the poet and critic Aurora de Albornoz. His father died when Ochoa was seven, and he and his mother moved to Málaga, where he attended elementary school through high school. His interest in biology was stimulated by the publications of the Spanish neurologist and Nobel laureate Santiago Ramón y Cajal. In 1923, he went to the University of Madrid Medical School, where he hoped to work with Ramón y Cajal, but Ramón y Cajal retired. He studied with father Pedro Arrupe, and Juan Negrín was his teacher:[4]

Negrin opened wide, fascinating vistas to my imagination, not only through his lectures and laboratory teaching, but through his advice, encouragement, and stimulation to read scientific monographs and textbooks in languages other than Spanish.[4]

Negrín encouraged Ochoa and another student, José Valdecasas, to isolate creatinine from urine.[4] The two students succeeded and also developed a method to measure small levels of muscle creatinine. Ochoa spent the summer of 1927 at University of Glasgow working with D. Noel Paton on creatine metabolism and improving his English skills. He also refined the assay procedure further and upon returning to Spain he and Valdecasas submitted a paper describing the work to the Journal of Biological Chemistry, where it was rapidly accepted,[6] marking the beginning of Ochoa's biochemistry career.[7]

Ochoa completed his undergraduate medical degree in the summer of 1929 and decide to go abroad again to gain further research experience. His creatine and creatinine work led to an invitation to join Otto Meyerhof's laboratory at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology in Berlin-Dahlem in 1929. At that time the institute was a "hot bed" of the rapidly evolving discipline of biochemistry, and thus Ochoa had the experience of meeting and interacting with scientists such as Otto Heinrich Warburg, Carl Neuberg, Einar Lundsgaard, and Fritz Lipmann in addition to Meyerhof who had received the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine less than a decade earlier.

In 1930 Ochoa returned to Madrid to complete research for his MD thesis, which he defended that year. In 1931, a newly minted MD, he married Carmen García Cobián. They did not have any children. He then began postdoctoral study at the National Institute for Medical Research in London, where he worked with Henry Hallett Dale. His London research involved the enzyme glyoxalase and was an important departure in Ochoa's career in two respects. First, the work marked the beginning of Ochoa's lifelong interest in enzymes. Second, the project was at the cutting edge of the rapidly evolving study of intermediary metabolism.[4]

Career and research

[edit]In 1933 the Ochoas returned to Madrid where he began to study glycolysis in heart muscle. Within two years, he was offered the directorship of the Physiology Section in a newly created Institute for Medical Research at the University of Madrid Medical School. Unfortunately the appointment was made just as the Spanish Civil War erupted. Ochoa decided that trying to perform research in such an environment would destroy forever his "chances of becoming a scientist." Thus, "after much thought, my wife and I decided to leave Spain." In September 1936 they began what he later called the "wander years" as they traveled from Spain to Germany, to England, and ultimately to the United States within a span of four years.[4][8]

Ochoa left Spain and returned to Meyerhof's Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Biology now relocated in Heidelberg, where Ochoa found a profoundly changed research focus. During his 1930 visit the laboratory work was "classical physiology," which Ochoa described as "one could see muscles twitching everywhere".[4] By 1936 Meyerhof's laboratory had become one of the world's foremost biochemical facilities focused on processes such as glycolysis and fermentation. Rather than studying muscles "twitch," the lab was now purifying and characterizing the enzymes involved in muscle action and those involved in yeast fermentation.

From then until 1938, he held many positions and worked with many people at many places. For example, Otto Meyerhof appointed him Guest Research Assistant at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg for one year. From 1938 until 1941 he was Demonstrator and Nuffield Research Assistant at the University of Oxford.

United States

[edit]Ochoa then went to the United States, where he again held many positions at several universities. Between 1940 and 1942, Ochoa worked for Washington University's School of Medicine.[9][10] In 1942 he was appointed research associate in medicine at the New York University School of Medicine and there subsequently became assistant professor of biochemistry (1945), professor of pharmacology (1946), professor of biochemistry (1954), and chair of the department of biochemistry.

In 1956, he became an American citizen.[5] He was elected to both the United States National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1957. In 1959, Ochoa and Arthur Kornberg were awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine "for their discovery of the mechanisms in the biological synthesis of ribonucleic acid and deoxyribonucleic acid". He was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1961.[11]

Ochoa continued research on protein synthesis and replication of RNA viruses until 1985, when he returned to now democratic Spain where he was a science advisor. Ochoa was also a recipient of U.S. National Medal of Science in 1978.

Severo Ochoa died in Madrid, Spain on 1 November 1993. Carmen García Cobián had died in 1986.

Long after his death, Spanish actress Sara Montiel claimed that she and Severo Ochoa were involved in a romantic relationship in the 1950s, as stated in an interview in Spanish newspaper El País: "The great love of my life was Severo Ochoa. But it was an impossible love. Clandestine. He was married, and besides, him doing research and me doing films wasn't a good match." [12]

Legacy

[edit]A new research center in the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM), that was planned in the 1970s, was finally open in 1975 (CBM) and named, after his dead, the Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa.[13]

In Leganés, Madrid, a hospital bears his name, as does the Madrid Metro station serving it, Hospital Severo Ochoa.

The asteroid 117435 Severochoa is also named in his honor.

In 2003 the Spanish General Post Office (Correos) issued a €0,76 postage stamp honoring Ochoa, as one of a pair featuring Spanish medical Nobel Prize winners[14] alongside Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

In June 2011, the United States Postal Service issued a stamp honoring him,[15] as part of the American Scientists collection, along with Melvin Calvin, Asa Gray, and Maria Goeppert-Mayer. This was the third volume in the series.

The main road in to the tourist resort Benidorm is named Avenida Dr. Severo Ochoa[16] in his honor.

References

[edit]- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1959". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 15 March 2023. Retrieved 15 March 2023.

- ^ cornberg, Arthur (1997). "Severo Ochoa (24 September 1905–1 November 1993)". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 141 (4): 479–491. JSTOR 987224.

- ^ Kornberg, Arthur (2001). "Remembering our teachers". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)44198-1. PMID 11134064. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ochoa, S. (1980). "A Pursuit of a Hobby". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 49: 1–30. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.49.070180.000245. PMID 6773467.

- ^ a b Severo Ochoa on Nobelprize.org

- ^ Ochoa, S.; Valdecasas, J. G. (1929). "A micromethod for the estimation of total creatinine in muscle". J. Biol. Chem. 81 (2): 351–357. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)83817-0.

- ^ Grunberg-Manago, Marianne (1997). "Severo Ochoa. 24 September 1905–1 November 1993: Elected For.Mem.R.S. 1965". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 43: 351–365. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1997.0020.

- ^ Singleton, R. Jr. (2007). "Ochoa, Severo." In New Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Noretta Koertge (ed.), vol. 5, pp. 305–12. Detroit: Charles Scribner's Sons.:]

- ^ "Severo Ochoa". www.nasonline.org. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ "Severo Ochoa". American Academy of Arts & Sciences. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Archived from the original on 23 November 2022. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ NÚÑEZ JAIME, VÍCTOR (13 October 2012). "En 54 años no ha salido nadie como yo". El Pais. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- ^ "Centro de Biologia Molecular Severo Ochoa". Archived from the original on 22 June 2007. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Correos. "Nobel Prize Philately". Archived from the original on 16 November 2023. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ United States Postal. "American Scientists". Archived from the original on 4 April 2011.

- ^ "Av. Dr. Severo Ochoa · 03503, Alicante, Spain". Archived from the original on 23 December 2022. Retrieved 23 December 2022.

External links

[edit]- Severo Ochoa on Nobelprize.org

- 1905 births

- 1993 deaths

- People from Valdés, Asturias

- Spanish biochemists

- 20th-century American biochemists

- American Nobel laureates

- History of genetics

- Nobel laureates in Physiology or Medicine

- 20th-century Spanish physicians

- National Medal of Science laureates

- Spanish Nobel laureates

- American people of Asturian descent

- Spanish emigrants to the United States

- Foreign members of the Royal Society

- Foreign members of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- Foreign members of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- Academic staff of Heidelberg University

- Complutense University of Madrid alumni

- Members of the German Academy of Sciences at Berlin

- Hispanic and Latino American scientists

- Presidents of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

- Washington University School of Medicine faculty

- 20th-century American physicians

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- New York University Grossman School of Medicine faculty