Carl Severing

Carl Severing | |

|---|---|

Carl Severing in 1919 | |

| Minister of the Interior | |

| In office 28 June 1928 – 27 March 1930 | |

| Chancellor | Hermann Müller |

| Preceded by | Walter von Keudell |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Wirth |

| Member of the Weimar Reichstag | |

| In office 6 February 1919 – 22 March 1933 | |

| 1919–1920 | Weimar National Assembly |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Constituency abolished |

| Member of the Prussian Landtag | |

| In office February 1919 – March 1933 | |

| Member of the Imperial Reichstag for Minden 3 | |

| In office 3 December 1903 – 6 February 1912 | |

| Succeeded by | Arthur von Posadowsky-Wehner |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1 June 1875 Herford, Prussia, German Empire |

| Died | 23 July 1952 (aged 77) Bielefeld, North Rhine-Westphalia, West Germany |

| Nationality | German |

| Political party | Social Democratic Party |

| Spouse | Emma Wilhelmine Twelker |

| Occupation | Metal worker |

Carl Wilhelm Severing (1 June 1875 – 23 July 1952) was a German union organizer and Social Democratic politician during the German Empire, Weimar Republic and the early post-World War II years in West Germany. He served as a Reichstag member and as interior minister in both Prussia and at the Reich level where he fought against the rise of extremism on both the left and the right. He remained in Germany during the Third Reich but had only minimal influence on reshaping the Social Democratic Party after World War II.

Severing came from a poor working class family in Westphalia. After completing an apprenticeship as a locksmith he became a member of the German Metalworkers' Union and rose rapidly in both the union and the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in Bielefeld. He won a seat in the Imperial Reichstag in 1907 but lost his bid for re-election in 1912. He remained active in the SPD, including as a writer for its Bielefeld newspaper.

Severing supported Germany during World War I in the belief that it was fighting a defensive war. After the Empire's defeat, he became a member of the First Reich Congress of Workers' and Soldiers' Councils in Berlin, the Weimar National Assembly and then the Weimar Reichstag, where he retained his seat until the National Socialists rose to power in 1933.

During the period of serious labor unrest that broke out in the industrial areas of the Ruhr valley and Upper Silesia in early 1919, Severing was appointed state commissioner with the task of defusing the situation. He won praise for doing so with a minimum use of force. Following the 1920 Kapp Putsch, Severing was named Prussian interior minister. During his three terms in office, he worked to democratize both the Prussian administration and its police force, primarily by removing officials who were not supporters of a republican form of government. He attempted to build a strong police force in the conviction that its use would lead to less violence and fewer deaths than would the Reichswehr when confronting internal unrest such as the 1921 central German uprising.

Severing was Reich interior minister from June 1928 to March 1930. He was faced with the increasing strength of extremist parties and with violence from both the left, primarily the Communist Party of Germany (KPD), and the right, including various Freikorps units and the Nazi Party. He had the Nazi SA banned in 1932 but in general resisted calls to ban extremist groups except when they posed a threat to the Republic. In the face of opposition from the SPD that he was seldom able to overcome, Severing also favored co-operation between the SPD and the extremist parties in the Reichstag, arguing that it would be worse to withdraw and leave them in control.

After Reich Chancellor Franz von Papen ousted the Prussian government in the 1932 Prussian coup d'état, Severing and the remainder of the SPD offered no resistance to a move that helped pave the way for Adolf Hitler to become German chancellor in 1933. Severing remained in Germany during the Third Reich where he faced only minor harassment. He had contacts with some of the parties involved in the 1944 assassination plot against Hitler but played no active role.

In the aftermath of World War II, Severing was contacted by and worked with the Allied occupation authorities and again became active in the SPD, but he never played a leading role because the party wanted a wholly new start. He was, however, a member of the parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia until his death in 1952.

Imperial era

[edit]Family and first political experience

[edit]Carl Severing came from a Protestant working class family in straitened circumstances in Herford, Westphalia, which was then a province of Prussia. His father Bernhard worked as a cigar sorter, and his mother Johanna was a seamstress. The family fell into hardship when his father became mentally ill. Carl and his half-brother had to help their mother sort cigars, a job that was done at home. A pastor offered to pay for Carl to attend high school and suggested that he become a pastor, but Carl wanted to be a musician. Since it turned out to be impossible to finance the study,[1] he attended public school and then began an apprenticeship as a locksmith, which he finished in 1892.

Although politics played no role in Severing's family, Carl showed an early interest in the socialist labor movement after a colleague introduced him to its goals. Immediately after his journeyman's examination, Severing joined the German Metal Workers' Union (DMV). He became the organization's secretary and in 1893 was elected to the local trade union cartel as a representative of the DMV. He was also a correspondent and contact for the Social Democratic newspaper Volkswacht from neighboring Bielefeld.

In 1894 Severing left Herford for Bielefeld where he gave up his employment in handcraft and switched to factory work. In Bielefeld, too, he became involved in the Social Democratic Party and the trade union. In 1895 he played a leading role in a failed strike involving a lockout and lost his job as a result.[2]

Switzerland

[edit]

Severing then went to Zürich where in 1895[2] he began work as a skilled laborer in a metal goods factory. He became involved in the Swiss Metalworkers' Union, which had independent sub-organizations for immigrant German workers. He also joined the local committee of German Social Democrats and the German Workers' Educational Association Eintracht ('Concord'). Within a short time Severing had established himself as a leading figure in the various associations.

Severing's political views became markedly more radical during his years in Switzerland. His criticism of the politics of the Social Democrats led him to resign from his functions in the Workers' Educational Association.[3] In his speeches he frequently spoke of world revolution and no longer only of improving the political and social condition of the workers. He observed from a distance that the SPD in East Westphalia was beginning to follow a distinctly pragmatic course and that the party was considering taking part in the Prussian state election, which tended to be viewed with scorn because of the Prussian three-class franchise that weighted votes based on the amount of taxes paid.

In 1898 Severing left Switzerland and returned to Bielefeld.

Rise in the Bielefeld labor movement

[edit]In 1899, after his return from Switzerland, Severing married a distant relative, Emma Wilhelmine Twelker, who was expecting his child. The couple had two children.

Due to the lack of support Severing encountered within the local SPD, he shifted his focus to union work. He rose rapidly in the field and in 1901 became managing director of the local branch of the German Metalworkers' Union. At the time the local union had enrolled only about 30% of the potential membership. During Severing's term of office, it increased sixfold; by 1906 the level of organization had reached 75%. The introduction of shop stewards contributed to his success. The system guaranteed the union's proximity to the concerns and needs of its members.

From his base in the metalworkers' movement, Severing extended his sphere of influence to Bielefeld's entire trade union organization, against fierce resistance from other unions. By 1906 he was the central figure in the city's labor movement. In both 1906 and 1910, Severing achieved wins for the workers without a strike. It was not until 1911 that there was a major work stoppage and it, too, was successful. In 1912 he resigned from his post at the metalworkers' union.

During the years when his predominant efforts were with trade unions, Severing's political views changed significantly. His revolutionary positions were replaced by a pronounced pragmatism that was frequently regarded as right wing within the party. His goal was no longer the dictatorship of the proletariat but the integration of workers into society. In this respect, he came closer to the revisionist positions he had once fought.

Entry into politics

[edit]Severing's influence on the Bielefeld labor movement during the Empire was based primarily on his success in the trade unions. Through the "unionization of the party",[4] his indirect influence on the SPD through close associates was great enough to enable him to dispense with taking a leading position in it himself.

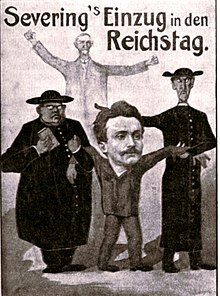

More important to him was the opportunity to have a parliamentary voice. He first ran for a Reichstag seat in 1903, at the time still a hopeless endeavor even though there had been a significant increase in Social Democratic voters. In the Reichstag election of 1907, he won a seat from the electoral district of Minden 3. His success was in contrast to the overall Reich results. In the so-called "Hottentot election", the Social Democrats lost a considerable number of voters and seats after they were branded as "enemies of the Reich" for opposing what came to be known as the Herero and Namaqua genocide in German South West Africa.[5]

With his victory Severing moved into the inner circle of decision makers. In the SPD parliamentary group, he became an expert member of numerous committees and a sought-after debater in their meetings. He also began to write regularly for the revisionists' theoretical Sozialistische Monatshefte (Socialist Monthly), and in the Bielefelder Volkswacht he wrote about his work in the Reichstag and his participation in various international union and socialist congresses.[6]

Severing's opponent in the 1912 Reichstag election was Arthur von Posadowsky-Wehner, a conservative who until 1907 had held numerous cabinet-level posts in the Reich government and who ran as the joint candidate of the Centre, National Liberal and German Conservative parties. Posadowsky defeated Severing in the runoff election because the base of the left-liberal German Progress Party, contrary to the recommendation of its party leadership, did not vote for him.

Even after losing his Reichstag seat, Severing remained one of the most influential "provincial princes" and played an important role in the party committee, a body that along with the executive board and the SPD Reichstag delegates represented the districts in the party as a whole. In 1912 Severing gave up his position at the German Metalworkers' Union. From 1912 to 1919 he was editor and de facto director of the Social Democratic Volkswacht newspaper in Bielefeld.[2]

World War I

[edit]Support for the war

[edit]Shortly before the start of the First World War, a large anti-war demonstration was held in Bielefeld at which Severing spoke cautiously in favor of Social Democratic support for a conflict that he saw as a defensive war: "But once the die is cast, there is only one goal for Social Democracy, too: to protect the German people by all means against power-hungry claims of the [Russian] peace czar." After the war began on 4 August 1914, he wrote "Inter arma silent leges. [In times of war, the law falls silent.] ... The war is here and we have to defend ourselves."[7] To legitimize the approval of war bonds by the Reichstag, he made use of socialist ideas of war policy as a means to achieve both social equality for workers and long overdue reforms.[8]

Severing remained in the pro-war camp during the following years. In the party committee in 1915, he denied SPD co-leader Hugo Haase the right to express his critical opinions and in 1916 attacked Karl Liebknecht, an outspoken opponent of the war, with polemical and partly false accusations.[9] Supported by the regional Social Democratic press, he succeeded in swearing the Bielefeld-Wiedenbrück SPD to the course of the party majority around its moderate pro-war co-leader Friedrich Ebert. After the anti-war wing of the SPD broke off to form the Independent Social Democratic Party (USPD) in April 1917, it played a significant and in some cases dominant role in parts of the Rhineland and Westphalia, but it was barely able to gain a foothold in East Westphalia.[10]

Reichstag peace resolution and war's end

[edit]At large public meetings, Severing and other Bielefeld Social Democrats repeatedly criticized war profiteers, "racketeers" and the public authorities' inability to combat the increasing hardships of the people. Severing viewed government intervention in the free market as "war socialism" and called for its continuation. "Not less but more socialism must be the rallying cry of the future."[11]

Although he had called for the subscription of war bonds only a short time before, Severing welcomed the Reichstag Peace Resolution of 1917 that called for a peace without annexations. He saw it in part as a step towards a democratic system and cooperation with other parties. When Germany concluded a dictated peace with Bolshevik Russia at Brest-Litovsk in clear contradiction of the negotiated peace called for in the peace resolution, Severing organized large demonstrations in Bielefeld. As in other places in the Reich, politically motivated strikes occurred in Bielefeld in January 1918. The local SPD placed itself at the head of the movement in order to steer it into moderate channels. The work stoppages ended after only two days. Friedrich Ebert described Severing's actions as a model for the entire Reich.[12]

November Revolution

[edit]

Due in large part to the close involvement of the SPD in local politics, Bielefeld was considered the quietest industrial city in Germany during the November Revolution of 1918 that brought down the Hohenzollern monarchy. In Bielefeld a people's and soldiers' council was formed rather than one made up of workers and soldiers as in most of the rest of Germany. Even though the SPD and the trade unions were behind it, they made it clear that it was open to other social groups. The program of the People's and Soldiers' Council that Severing had developed was aimed solely at maintaining public order and ensuring provisions; it involved no political claims. On 17 November the council elected an implementation committee that consisted of one-third each workers, salaried employees and representatives of the middle class.

Severing was elected as a delegate to the first Reich Congress of Workers' and Soldiers' Councils in Berlin, where he was one of the three chairmen of the Majority Social Democrats (MSPD),[13] the main group of the SPD after the USPD split off in 1917. Although he supported Friedrich Ebert's policies in principle, he and Hermann Lüdemann acted against Ebert's intentions when they introduced a motion for the socialization of all industries that were "ready" for it.[14] Overall Severing contributed considerably to the general acceptance of the MSPD's positions.[15]

Weimar Republic

[edit]Weimar National Assembly

[edit]In 1919–1920 Severing was a member of the Weimar National Assembly, the interim parliament that wrote the constitution for the new German republic. After it completed its work, he served as a Reichstag deputy until just after the 1933 election victory of the National Socialists. During the same years he was also a member of the Prussian State Parliament (Landtag). As one of the MSPD's negotiators in the formation of the Weimar Coalition, Severing played an important role as a proponent of the alliance of MSPD, the liberal German Democratic Party (DDP) and the conservative Catholic Centre Party. It was due in particular to Severing's negotiating skills that the Centre Party participated in the coalition government.[16][17] In the National Assembly he campaigned for the acceptance of the Treaty of Versailles in the belief that the risks of a rejection could not be justified.[18]

Reich and state commissioner in the Ruhr

[edit]In the industrial Ruhr valley, the trade unions and the MSPD had lost much of their influence to the USPD and the German Communist Party (KPD). A movement involving all workers' parties spread in the region in early 1919 and sought the nationalization of the mining industry. In the course of a walkout, the syndicalist General Miners' Union was formed.

Severing was appointed Reich and state commissioner (Staatskommissar) and given the task of defusing the situation. Both the Reich and Prussian governments wanted to have a politician who would minimize the use of force while working with the military commander in Münster, General Oskar von Watter. The decisions Severing made were primarily an attempt to reach an understanding with the striking workers and to remedy existing hardships and grievances. Violence was to be used only when it was provoked. He was able to settle the strike quickly using both repression and negotiations. One of his orders provided for the forced conscription of all able-bodied men to emergency labor, and he had the ringleaders of the strike arrested. Those willing to work, on the other hand, received special rations. When the miners were granted seven-hour shifts, the strike began to collapse.[19]

After the Ruhr strike was settled, Severing remained in his position as commissioner with the goal of helping to achieve a lasting pacification of the situation in the coalfields. He worked in particular to improve the food supply. Since the Prussian government had come to value him as a crisis manager, it temporarily sent him to the industrial areas of Upper Silesia, and in the Ruhr his duties were extended to include neighboring regions. With the support of two other SPD parliamentarians, he mediated numerous conflicts between employers and employees.[20]

At his home base in Bielefeld, Severing temporarily lost control of the situation. When riots broke out in June 1919, he had to flee and was forced to impose a state of siege on the city. The measure led to conflicts with the Bielefeld SPD.[21]

The situation in the coalfields remained for the most part calm until the beginning of 1920. When it worsened again due to railroad and miners' strikes, Severing took repressive measures that included the dismissal of striking railroad workers. He took similar action against the syndicalists' attempt to impose six-hour shifts in the mining industry. To help ease the coal crisis in the Reich, he enforced overtime shifts. In return he campaigned for better provisions and pay.

The Majority Social Democrats recognized Severing's efforts to normalize the situation in the Rhineland-Westphalian industrial area at the party congress of 1919. Part of the reason behind it was that Severing – unlike Defense Minister Gustav Noske – was able to stand up to the military.[22]

Kapp Putsch and Ruhr uprising

[edit]

A serious threat to the Republic arose from the political right on 13–18 March 1920 with the Kapp Putsch, an attempt in Berlin to set up an autocratic government in place of the Weimar Republic. Severing, who was in East Westphalia at the beginning of the putsch, helped organize resistance to it there. Together with the governor of the province of Westphalia, he took a strong stand on the side of the legitimate government. The military commander in Münster, General Watter, was secretly close to Kapp and refused to sign an appeal to oppose him. In the Ruhr, the general strike against the putsch developed into an insurrectionary movement directed against Watter and the Freikorps under his command. For a time, an impromptu Ruhr Red Army was able to prevail against the Freikorps. It was only after his troops were defeated that Watter on 16 March declared his support for the constitutional government.

The strikers did not heed Severing's call on 21 March to return to work after Kapp's defeat. For a time, the Ruhr Red Army, in what came to be known as the Ruhr uprising, dominated the entire Ruhr region. Severing made it clear that the movement could not be ended by military means alone[23] and helped broker the Bielefeld Agreement. It was, however, only partially successful. Especially in the west, fighting continued and resulted in the Reichswehr and Freikorps entering the Ruhr. Even Severing saw no alternative to military intervention. His concern then was no longer with keeping the Reichswehr out but with preventing unnecessary bloodshed.[24] The entry of the troops was nevertheless accompanied by the abuse and killing of a large number of insurgents. The death toll was estimated at around 1,000 rebels and 200 Reichswehr soldiers.[25] Severing tried to end the violence and eventually succeeded in having summary executions stopped. It was clear to him from that point that the army was not suited for maintaining internal order since its use increased resentment among the population.[26]

Start of the "Severing system" in Prussia

[edit]After the Kapp Putsch, there were changes in the government of Prussia. The new leaders included Otto Braun (SPD) as minister president and Severing as interior minister. They did not pursue policies that were more leftist than those of their predecessors, but they differed from them in their greater clarity of purpose and the energy of their policies.[27] Severing's duties included control of the Prussian administration as well as its police. His central task was to republicanize them.

Republicanizing the administration

[edit]The first step in Severing's measures to republicanize the administration was to remove those civil servants who had joined the putschists or openly sympathized with them. His prerequisite for civil servants was that they should support democracy out of conviction rather than reluctantly accepting it as a given. About one hundred high officials were removed from their posts and replaced with supporters of the Republic. Knowing the strength of the right-wing German National People's Party (DNVP) in the district councils (Landräte) in Prussia's eastern provinces, Severing turned down the demand by the political right for the district councils to be elected. By 1926, at the end of his term, all but one of the governors, all of the district presidents, and more than half of all district council officers had been appointed by republican governments. The top positions were almost universally held by supporters of the parties of the Weimar Coalition.

Severing changed very little in the basic structure of the Prussian administration out of respect for its effectiveness. He did not succeed, for example, in breaking the monopoly of lawyers among high-ranking civil servants. Only a few non-lawyers from outside managed to get into leading positions in the administration.[28][29]

Police reform

[edit]Alongside the democratization of the administration, reform of the police was the most important part of Severing's system. In the years after the revolution, he became convinced that only a powerful police force could prevent the use of the military when public order was disturbed domestically. As in his administrative reforms, supporters of the Kapp putsch were dismissed from the police force, especially the security police.

Severing pushed through the nationalization of the previously partly municipal police forces and established police headquarters and presidencies. In June 1920, the Allies in their "Boulogne Note" called for the dissolution of paramilitary units and the establishment of a regular police force. Out of a total of 150,000 men, 85,000 were to be assigned to Prussia. Severing brought Wilhelm Abegg into the ministry to organize the new Schutzpolizei (protection police). Schutzpolizei officers generally came from the ranks of the old army and for the most part were not wholly committed to the Republic.[30] To attempt to counteract the problem, Severing placed great emphasis on character formation and had a number of police schools established.[31]

Prohibition of paramilitary groups and the central German uprising

[edit]

Supported by the new police force, Severing was able to begin banning and dissolving paramilitary groups such as the Orgesch and Schutzwehren (a type of home guard) in 1920.[32] In principle Severing saw a ban on anti-republican organizations as a last resort. As long as they or their members did not actively oppose the Republic, he did not intervene. In 1921 he repealed the decree that prohibited communists from holding offices in state and municipal administration. For him mere membership was not enough for exclusion. Only when radical groups became subversive did Severing intervene. His graduated approach led to criticism from some Social Democrats who wanted harsher steps.[33]

In March 1921 Severing sent the Schutzpolizei to restore order in areas of central Germany that had remained unsettled since the Kapp Putsch. He wanted both to forestall the use of the Reichswehr and to test the new police units.[34] In the fighting that ensued, the police quickly prevailed, especially since KPD supporters did not resist except in the Ruhr and Hamburg. A comparison of the damage and casualties between the fighting in the Ruhr in 1920 and the central German uprising confirmed Severing in his view that the use of police was preferable to the military.[35]

Change of government and new term of office

[edit]The Prussian state election of 1921 led to a significant weakening of the SPD. A minority government was formed by the Centre Party and the German Democratic Party (DDP) under Minister President Adam Stegerwald (Centre). Severing was replaced by Alexander Dominicus (DDP).[36] When in Severing's view Domenicus began to abandon the domestic policies that he had instituted, he argued for grand coalitions in both the Reich and Prussia. Efforts then began to form a coalition in Prussia that would include the SPD and German People's Party (DVP) in place of Stegerwald's minority government. Severing led the negotiations on behalf of the Social Democrats and succeeded in persuading the DDP to leave the government. On 1 November 1921, the Stegerwald government resigned, and Otto Braun again became minister president with Severing as minister of the interior.

During Severing's first term in office, communists were seen as the most dangerous enemies of the Republic, but the situation had changed, especially after right-wing extremists assassinated Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau (24 June 1922) and failed in an attempt against former minister president Philipp Scheidemann (4 June 1922). Severing took up the fight against the right in accordance with an emergency decree from Reich Chancellor Joseph Wirth. In Prussia, numerous right-wing organizations were banned, including the Stahlhelm in 1922, although the ban was overturned by the Reich court. Braun and Severing's attempt to take action against illegal Reichswehr units failed as well, largely due to the resistance of General Hans von Seeckt. In the face of opposition from the Centre, Severing succeeded in replacing additional anti-Republic high officials, especially in Westphalia and the Rhine Province.[37]

Crisis year 1923

[edit]When French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr in 1923 because Germany had defaulted on its World War I reparations payments, Severing was one of the strongest advocates of passive resistance as opposed to the active and violent resistance promoted and carried out by right-wing groups. Severing's fight against the right included banning the German Völkisch Freedom Party (DVFP) on 22 March 1923. In spite of accusations from the right and from Reich Chancellor Wilhelm Cuno, Severing did not ignore the dangers from the extreme left. He banned the paramilitary bodies aligned with the KPD known as the Proletarian Hundreds. Against the right-wing "protective formations", Severing formed an alliance with Reichswehr chief Hans von Seeckt. It had the unintended effect of facilitating the establishment of the Black Reichswehr, and the goal of separating the Reichswehr from right-wing paramilitaries failed.[38]

Passive resistance could not be sustained in the face of the growing inflation that it was helping to fuel. The crisis was overcome under the new Reich government led by Gustav Stresemann of the German People's Party (DVP), in which the SPD initially participated at Severing's instigation.[39][40] SPD participation ended after less than two months, however, because of planned restrictions on the eight-hour day. A large number of leading Social Democrats, notably Paul Löbe, spoke in favor of withdrawing their ministers under pressure from the unions. One of the few who advocated remaining in government was Severing. He feared a shift to the right under a government without Social Democratic participation. He implored his party in vain to "Think of the consequences!"[41]

Even though Severing had banned extreme parties, once the acute crisis had been overcome, he and Reich President Friedrich Ebert were in favor of allowing the KPD, Nazi Party and DVFP, which had been banned at the Reich level, to participate the Reichstag election of May 1924. He argued that banning would contribute to radicalization.[42] Only the KPD, which went from 4 to 62 seats in the Reichstag, ran in the election.

Minister under Marx and Braun

[edit]

In Prussia the DVP withdrew its ministers, and on 10 February 1925, Wilhelm Marx (Centre) was elected minister president. He left Severing in office, hoping that it would win over the SPD to support the government. Marx failed within his own ranks, partly because politicians from the right wing of the Centre Party such as Franz von Papen refused to follow the government due to its support for Severing. The stalemate was overcome by the formation of a new Otto Braun government in which Severing was once again Prussian minister of the interior.[43]

Severing was by then weary of holding office. His plans for a major administrative reform that included the dissolution of district governments failed. He also made no further progress in the area of democratizing the administration, especially since similar measures were not taken at the Reich level. The personal relationship between Braun and Severing had also deteriorated. Braun felt that Severing was no longer acting aggressively enough against the Republic's enemies. He took advantage of a long illness of Severing's to move against right-wing politicians and groups and to make personnel decisions in the Interior Ministry without consulting Severing.[44] Severing was also subject to constant and sometimes defamatory attacks by the extreme left and right. In October 1925 the DNVP brought a vote of no confidence against him in the Prussian state parliament. He defended himself vigorously and the motion failed, but it took a heavy toll on Severing's self-confidence.[45] He officially resigned on 6 October 1926 and was succeeded by Albert Grzesinski.[46][47]

Reich minister of the interior 1928–1930

[edit]While out of office, Severing campaigned for the formation of a grand coalition at the Reich level. Along with Otto Braun and Rudolf Hilferding, he succeeded in persuading the 1927 SPD party congress to adopt a resolution that sought to win positions of power at all political levels. The opportunity to regain influence at the Reich level came with the Reichstag election of 1928. In the campaign, the SPD focused on its opposition to the construction of the heavy cruiser Deutschland. Severing, who did not share his party's position, nevertheless gave the keynote speech in the Reichstag against its construction. With the slogan "Food for the children, not a heavy cruiser", the SPD made strong gains in the election. Even before Hermann Müller's government was formed, it was clear that Severing would become Reich minister of the interior. He led the difficult coalition negotiations for the SPD. Attempts to conclude a formal coalition agreement failed, with the result that initially only a "government of personalities" was formed.[48]

The office of Reich minister of the interior had considerably less scope for shaping policy than the post in Prussia, especially since administration and police were largely a matter for the states. Severing began to reshuffle the top staff of the ministry so that the positions would be filled by supporters of the Republic. In spite of Severing's personal disagreements with Grzesinski at the Prussian Interior Ministry, Prussia and the Reich cooperated more intensively than ever in domestic politics during the grand coalition.[49]

Defense policy

[edit]

At the SPD party congress of 1929, a dispute arose over a defense program that a working commission had presented. The left-wing "class struggle group" around Paul Levi was categorically opposed to the military, which it saw as a means of oppressing the working class. Severing on the other hand warned against "constantly criticizing the Reichswehr". He said that anyone who did not also see the positive could not republicanize it. Through his speech he helped win a majority for a somewhat modified commission draft.[50]

Fight against the political extremes

[edit]In 1929 protests rose among Germany's right-wing camps against the Young Plan for the settlement of World War I reparations. Media publisher and conservative DNVP politician Alfred Hugenberg in particular pushed a referendum against the Young Plan. Severing was at the forefront of those who opposed the referendum and resisted the attacks of the Hugenberg press. The referendum failed due to the low turnout of only 15%.[51]

On the left, the KPD agitated mainly against the SPD after it adopted the Comintern's theory of social fascism which held that social democracy was a variant of fascism because it stood in the way of a dictatorship of the proletariat. The Roter Frontkämpferbund (Red Front Fighters' League), a paramilitary group associated with the KPD, was in particular intent on provocation. Prussian police moved harshly against a banned demonstration it held on 1 May 1929. Civil war-like clashes that came to be known as the Blutmai ('blood May') broke out in Berlin. Afterwards Albert Grzesinski urged Severing to issue a Reich-wide ban on the Red Front Fighters' League. It was already banned in Prussia, and the interior ministers of the other states soon followed his lead. Severing was skeptical about the move because it contributed to the radicalization of the KPD. He considered more far-reaching plans to ban the KPD altogether to be unfeasible.[52][53]

In view of the developments on the extreme left and right, Severing felt that it was necessary to pass an extension of the Law for the Protection of the Republic (Gesetz zum Schutze der Republik), which expired on 22 July 1929. The law had banned organizations that opposed the "constitutional republican form of government" as well as their printed matter and meetings. After a first draft of the extension failed in the Reichstag, a slightly weakened draft that no longer required a two-thirds majority was adopted.

End of the Müller government

[edit]

After the death of its party leader Gustav Stresemann, the German People's Party (DVP) began to try to push the SPD out of government. On 27 March 1930 the Müller government broke up over a dispute about unemployment insurance that was heightened by the onset of the Great Depression. Heinrich Brüning of the Centre Party had introduced a compromise proposal that was close to the DVP's position and would have meant an overall shift to the right in social policy. Severing pushed for acceptance in order to save the government, arguing that the compromise would be better than leaving the Republic to the right-wing parties, but he was unable to convince the majority of the SPD.[54][55]

Prussian minister of the interior in the crisis of the Republic

[edit]After the Reichstag election of 1930, in which both the KPD and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) made significant gains, Severing, Otto Braun and Ernst Heilmann argued for the SPD Reichstag membership to tolerate Heinrich Brüning's government. They believed that the first presidential government (one that used constitutional emergency decrees issued by President Paul von Hindenburg to override Reichstag opposition) was the lesser evil in the face of the strengthened National Socialists.[56]

After Albert Grzesinski had to resign as Prussian minister of the interior because of a private affair, Severing again took the position on 21 October 1930. Severing's return to office gave the majority of supporters of the Republic hope that the fight against the political extremes would be successful, while the far right took the appointment as a provocation. For the KPD, Severing was the "embodiment of social fascism".[57]

Severing soon realized that the Schutzpolizei were only of limited use as a protective force for the Republic. A considerable number of them, especially the officers, leaned toward the Stahlhelm and the NSDAP. In large part at Severing's urging, Brüning had an emergency decree issued that made it possible to take stronger action than before against political extremists. It was followed by other similar emergency decrees that also led to restrictions on fundamental rights. In the first three months, there were more than 3,400 police actions for political crimes, with the majority of over 2,000 cases directed against the KPD.[58]

When in the Reich presidential election of 1932, Braun, Brüning and others wanted to put forward Hindenburg as the candidate, Severing was skeptical, knowing that the Reich President often listened to advisors from the right-wing camp. Instead, he pushed without success for Hugo Eckener, a popular captain of Zeppelins who was loyal to the Republic. When the decision was made in favor of Hindenburg, Severing campaigned for him with all his energy. He organized the "Republican Action" which campaigned across party lines for Hindenburg. He was also able to acquire funds from the Reich government and Prussia for the successful election campaign against Adolf Hitler.[59]

Between the two presidential election periods, Severing had Nazi Party buildings searched. When highly incriminating material such as purge lists was found, he lobbied the Reich government successfully to ban the paramilitary Nazi SA. It went into effect on 13 April 1932 but largely came to nothing because the NSDAP had been warned in advance by staff from the Prussian Ministry of the Interior.[60]

Caretaker Prussian government 1932

[edit]In the 1932 Prussian state election, the NSDAP and KPD won 52% of the total vote, leading to a situation in which no party was able to form a government. Severing initially favored participation by the Nazis because he thought that it would de-mystify the movement. Later he argued that the Braun cabinet should remain in office on a caretaker basis. "Staying until replaced and undauntedly doing one's duty, whatever may come – that is perhaps the heaviest sacrifice yet called for by the party and by those closest to it. But it must be made because the constitution and the welfare of the people demand it."[61] After the de facto withdrawal of Otto Braun due to ill health, Severing was the dominant figure in the caretaker government. The situation became more difficult for the Prussian government after the fall of Chancellor Brüning on 30 May 1932.[62] He was replaced by Franz von Papen.

1932 Prussian coup d'état (Preussenschlag)

[edit]

From the beginning, the Papen cabinet worked to oust the caretaker Prussian government. A pretext for the so-called Preussenschlag was found in the 17 July 1932 Altona Bloody Sunday, a confrontation between police, supporters of the KPD and the Nazi SA that left 18 people dead.[63] On the morning of 20 July 1932, von Papen summoned Severing and two other ministers to his office and told them that Hindenburg had appointed him, Papen, Reichskommissar for Prussia because of the Prussian government's inability to guarantee law and order. He took over the affairs of government and dismissed Severing and Minister President Braun. The Ministry of the Interior was taken over by the mayor of Essen, Franz Bracht. The Prussian ministers protested against the measures, calling them unconstitutional. Severing declared, "I yield only to violence." A state of siege was then imposed on Berlin, and the Reichswehr was deployed. The Prussian ministers refrained entirely from offering resistance. In the afternoon of the same day, Severing, who commanded a police force of 90,000 men, allowed himself to be driven from his office and ministry by a deputation of the newly appointed police chief and two policemen. Other leading republican-minded police officers and public officials were removed from office over the next few days. As their only countermeasure, the ministers appealed to the State Constitutional Court (Staatsgerichtshof). Even though the government was partially vindicated in the hearing that took place in the fall, the ministers had lost their influence by giving up their posts.[64]

After the Preussenschlag, meetings of the powerless state government continued to be held, but Severing seldom participated. Instead, he found himself in an almost constant campaign as a symbolic figure for supporters of the Republic. He was the last SPD politician to make a campaign speech on the radio, although his efforts did nothing to change the party's loss of votes in the July 1932 Reichstag election. In the final phase of the Republic, Severing was one of the few leading Social Democrats to advocate support for the new Reich chancellor, Kurt von Schleicher, as a means to forestall Hitler.[65]

Under National Socialism

[edit]Beginning of National Socialist rule

[edit]The SPD was restricted in how it could conduct its election campaign for the Reich and state election in March 1933. Severing was allowed to give only two campaign speeches. He was arrested on charges of embezzling state funds but was released for the 23 March Reichstag session that dealt with the Enabling Act of 1933, which allowed the chancellor (Hitler) to enact laws without the involvement of the Reichstag. Severing was the last to cast his vote. He reported, "The presence of the SA and SS in the corridors and in the meeting room … intensified the threatening tone of the proclamation. ... With the 'No' card in my raised right hand, I walked from my seat through the rows of SA and SS men to vote."[66] Severing did not participate in the vote on an enabling act for Prussia on 18 May 1933 because he had already resigned his seat in the state parliament.[67]

Severing decided against emigration after the Nazis gained power in Germany. He did not want to leave his followers, especially those in Bielefeld, nor could he imagine a life abroad. Until the SPD was banned in June, he was part of the SPD leadership around Paul Löbe that fought the exile party's claim to leadership at home. After that he sought to adapt to the new circumstances.[68]

Life during the Nazi regime

[edit]Severing was not arrested again, although he was harassed and put under surveillance. Due to threats from the SA and other sources, he had to leave Bielefeld several times but otherwise remained unmolested. He withdrew from the public eye and initially kept away from resistance groups. He did, however, maintain close contact with former leading Social Democrats.

He made his stance towards the regime clear in small gestures such as refusing to fly the swastika flag, but when in 1935 the SPD in exile called for the Saarland to vote against reunification with the Reich, Severing spoke out in favor of it in the conviction that the Nazi regime would last only a short time and that there was a danger that otherwise the region would remain permanently outside Germany. For the SPD in exile, the statement was so outrageous that they believed it was a forgery.

Severing's son was killed in action during World War II.

Relationship to the resistance

[edit]When the frequent bombing raids against Germany made it clear to Severing that continuing the war would be disastrous, he began to make contact with resistance circles, in particular to Wilhelm Leuschner and Wilhelm Elfes. They planned the founding of a workers' party for the post-Hitler period that would overcome the previous division of the labor movement into Christian, Communist and Social Democratic contingents. Severing declined any additional active participation in the resistance because he considered the planned overthrow far too risky and unrealistic.[69] In spite of his contacts, Severing was not arrested after the failure of the 20 July 1944 assassination attempt against Hitler.[70]

Postwar

[edit]Immediately after the end of the war, Severing advised the occupying authorities, first American and later British, on filling positions. He continued to play a leading role in the SPD, although his idea of a workers' party bridging the pre-war political camps was not realized. He nevertheless remained focused on cooperation between the SPD and the other democratic parties. He also entered into dialogue with the churches, especially in Catholic areas.

On 3 September 1945, administrative leaders of the British occupation zone met at Severing's home. They designated Hamburg Mayor Rudolf Petersen and Severing as the German liaison officers with the occupation authorities. Due to the death of his wife, Severing was unable to attend the Wennigser Conference at which Kurt Schumacher asserted his claim to leadership of the SPD in the Western zones. In the British zone, the regular conferences of the individual states were to be chaired by Severing. He also negotiated with the Ruhr miners to persuade them to produce more and made proposals to reform the police force. Without a formal office, Severing held a stronger position than he ever did later.[71]

Campaign against Severing

[edit]By the fall of 1945, Severing's influence had begun to wane significantly. The cause was a campaign initiated by the East German KPD that accused him of having received a pension from the Nazi regime. He was also criticized for his behavior during the 1932 Preussenschlag. Those and other accusations were based in part on the lack of clarity as to why Severing was able to survive the Nazi period largely unmolested. Severing tried with little success to fight back against the campaign.

There was also criticism of him within the SPD. To many, Severing, Paul Löbe and Gustav Noske were ill-suited as leaders for a new beginning. Schumacher took a similar view and ousted him from the SPD leadership. The fact that the SPD in Westphalia did not put him at the top of the list for the first state election in North Rhine-Westphalia embittered him.[72]

Final years

[edit]

During negotiations to form the first cabinet of North Rhine-Westphalia under Rudolf Amelunxen (Centre Party), Severing was head of the SPD's negotiating delegation. He had particularly heated disputes with Konrad Adenauer,[73] who objected to the appointment of Severing's son-in-law Walter Menzel to the Ministry of the Interior and held Severing responsible for forming a government without Adenauer's party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU). Severing was elected to the first state parliament of North Rhine-Westphalia on 20 April 1947 and was a member until his death.[74] In 1947 he was again instrumental in the negotiations for a new government. In the parliament, Severing was a moral authority, taking his mandate very seriously. He delivered the speech at the inauguration of the new parliament building.[75]

By the time he died in July 1952, Severing had lost almost all political influence. He was nevertheless still highly respected. The state parliament held a funeral service for him, and thousands took the opportunity to pay their last respects. More than 40,000 people took part in his funeral procession.[76]

References

[edit]- ^ Koszyk, Kurt (1975). "Carl Severing". In Stupperich, R. (ed.). Westfälische Lebensbilder [Westphalian Life Portraits] (in German). Vol. 11. Münster: Aschendorff. pp. 173f.

- ^ a b c Michaelis, Andreas (14 September 2014). "Carl Severing 1875–1952". Deutsches Historisches Museum. Retrieved 26 February 2023.

- ^ Koszyk 1975, p. 176.

- ^ Ditt, Karl (1982). Industrialisierung, Arbeiterschaft und Arbeiterbewegung in Bielefeld, 1850–1914 [Industrialization, Workers and the Labor Movement in Bielefeld, 1850–1914] (in German). Dortmund: Gesellschaft für Westfälische Wirtschaftsgeschichte. p. 147. ISBN 9783921467305.

- ^ "Der Reichstag und die "Hottentottenwahl" von 1907" [The Reichstag and the "Hottentot Elections" of 1907 DHM] (PDF). Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Koszyk 1975, p. 180.

- ^ Alexander, Thomas (1992). Carl Severing. Sozialdemokrat aus Westfalen mit preussischen Tugenden [Carl Severing. Social Democrat from Westphalia with Prussian Virtues]. Bielefeld: Westfalen Verlag. p. 73. ISBN 3-88918-071-X.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 72–74.

- ^ Alexander 1992, p. 74.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Alexander 1992, p. 84.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 84–87.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 91–102.

- ^ Winkler, Heinrich August (1984). Von der Revolution zur Stabilisierung. Arbeiter und Arbeiterbewegung in der Weimarer Republik 1918 bis 1924 [From Revolution to Stabilization. Workers and the Labor Movement in the Weimar Republic 1918 to 1924] (in German). Berlin / Bonn: Dietz. p. 104. ISBN 3-8012-0093-0.

- ^ Koszyk 1975, p. 185.

- ^ Alexander 1992, p. 107.

- ^ Koszyk 1975, p. 186.

- ^ Koszyk 1975, p. 187.

- ^ Winkler 1984, p. 174.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 108–112.

- ^ Alexander 1992, p. 113.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Winkler 1984, p. 328.

- ^ Winkler 1984, p. 334.

- ^ Wulfert, Anja (22 January 2002). "Der Märzaufstand 1920" [The March Uprising 1920]. Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German). Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ Alexander 1992, p. 323.

- ^ Winkler 1984, p. 323.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 127–129.

- ^ Winkler 1984, p. 340.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 129–131.

- ^ Koszyk 1975, p. 190.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 13f.

- ^ Koszyk 1975, pp. 190f.

- ^ Winkler 1984, p. 516.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 134–136.

- ^ Alexander 1992, p. 134.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 140–142.

- ^ Winkler 1984, p. 557.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 142–146.

- ^ Winkler 1984, pp. 601f.

- ^ Winkler 1984, pp. 631, 661.

- ^ Winkler 1984, pp. 692f.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 147–150.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 152f.

- ^ Koszyk 1975, p. 192.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 151–154.

- ^ "Grzesinski Nachfolger Serverings" [Grzesinski Severing's Successor]. Vorwärts (in German). 6 October 1926. p. 1. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 155–160.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 160–162.

- ^ Winkler 1984, pp. 631–635.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 171f.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 172f.

- ^ Winkler 1984, p. 677.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 178f.

- ^ Winkler 1984, pp. 781f, 805–807, 819.

- ^ Alexander 1992, p. 182.

- ^ Winkler 1984, pp. 252f.

- ^ Winkler, Heinrich August (1990). Der Weg in die Katastrophe. Arbeiter und Arbeiterbewegung in der Weimarer Republik 1930 bis 1933 [The Road to Catastrophe. Workers and the Labor Movement in the Weimar Republic 1930 to 1933] (in German) (2 ed.). Berlin / Bonn: Dietz. pp. 310f. ISBN 3-8012-0095-7.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 185–190.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 191–193.

- ^ Alexander 1992, p. 194.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 193–197.

- ^ Scheuermann-Peilicke, Wolfgang (14 July 2021). "Der "Altonaer Blutsonntag" 1932" [The Altona Bloody Sunday 1932]. Deutsches Historisches Museum (in German). Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 197–201.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 206–211.

- ^ Alexander 1992, p. 214.

- ^ Ribhegge, Wilhelm (2008). Preussen im Westen: Kampf um den Parlamentarismus in Rheinland und Westfalen, 1789–1947 [Prussia in the West: The Struggle for Parliamentarism in the Rhineland and Westphalia, 1789–1947] (in German). Münster: Aschendorf. p. 589. ISBN 9783402054895.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 211–215.

- ^ Ribhegge 2008, p. 608.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 222f.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 225–234.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 234–238.

- ^ Ribhegge 2008, p. 650.

- ^ "Detailansicht des Abgeordneten Dr.h.c. Carl Severing" [Detail of the Deputy Dr.h.c. Carl Severing]. Landtag Nordrhein-Westfalen (in German). Retrieved 1 March 2023.

- ^ Alexander 1992, pp. 241–249.

- ^ "Minister und Arbeiter folgten seiner Bahre. 40.000 gaben Staatsminister a.D. Severing das letzte Geleit" [Ministers and workers followed his bier. 40,000 paid their last respects to former State Minister Severing.]. Bielefeld Freie Presse (in German). 28 July 1952.

External links

[edit]- 1875 births

- 1952 deaths

- People from Herford

- Politicians from the Province of Westphalia

- German Calvinist and Reformed Christians

- Social Democratic Party of Germany politicians

- Interior ministers of Germany

- Members of the 12th Reichstag of the German Empire

- Members of the Weimar National Assembly

- Members of the Reichstag 1920–1924

- Members of the Reichstag 1924

- Members of the Reichstag 1924–1928

- Members of the Reichstag 1928–1930

- Members of the Reichstag 1930–1932

- Members of the Reichstag 1932

- Members of the Reichstag 1932–1933

- Members of the Reichstag 1933

- Interior ministers of Prussia

- Members of the Landtag of Prussia