Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution: Difference between revisions

| Line 68: | Line 68: | ||

The new States of Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii are the only states never to have elected U.S. Senators under the original design of the Constitution. Oklahoma (1907) and New Mexico (1912), two other new states, apparently only elected U.S. Senators by the Legislature once. |

The new States of Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii are the only states never to have elected U.S. Senators under the original design of the Constitution. Oklahoma (1907) and New Mexico (1912), two other new states, apparently only elected U.S. Senators by the Legislature once. |

||

==mjghdnmdhgn |

|||

==Proposal and ratification== |

|||

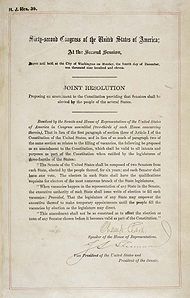

Congress proposed the Seventeenth Amendment on May 13, 1912 and the following states ratified the amendment:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.usconstitution.net/constamrat.html|title=Ratification of Constitutional Amendments|accessmonthday=February 24|accessyear=2007|last=Mount|first=Steve|year=2007|month=January}}</ref> |

|||

# Massachusetts (May 5, 1912) |

|||

# Arizona (June 6, 1912) |

|||

# Minnesota (June 10, 1912) |

|||

# New York (January 15, 1913) |

|||

# Kansas (January 17, 1913) |

|||

# Oregon (January 23, 1913) |

|||

# North Carolina (January 25, 1913) |

|||

# California (January 28, 1913) |

|||

# Michigan (January 28, 1913) |

|||

# Iowa (January 30, 1913) |

|||

# Montana (January 30, 1913) |

|||

# Idaho (January 31, 1913) |

|||

# West Virginia (February 4, 1913) |

|||

# Colorado (February 5, 1913) |

|||

# Nevada (February 6, 1913) |

|||

# Texas (February 7, 1913) |

|||

# Washington (February 7, 1913) |

|||

# Wyoming (February 8, 1913) |

|||

# Arkansas (February 11, 1913) |

|||

# Maine (February 11, 1913) |

|||

# Illinois (February 13, 1913) |

|||

# North Dakota (February 14, 1913) |

|||

# Wisconsin (February 18, 1913) |

|||

# Indiana (February 19, 1913) |

|||

# New Hampshire (February 19, 1913) |

|||

# Vermont (February 19, 1913) |

|||

# South Dakota (February 19, 1913) |

|||

# Oklahoma (February 24, 1913) |

|||

# Ohio (February 25, 1913) |

|||

# Missouri (March 7, 1913) |

|||

# New Mexico (March 13, 1913) |

|||

# Nebraska (March 14, 1913) |

|||

# New Jersey (March 17, 1913) |

|||

# Tennessee (April 1, 1913) |

|||

# Pennsylvania (April 2, 1913) |

|||

# Connecticut (April 8, 1913) |

|||

Ratification was completed on April 8, 1913, having the required three-fourths majority. |

|||

The amendment was subsequently ratified by the following state: |

|||

Louisiana (June 11, 1913) |

|||

The following state rejected the amendment: |

|||

Utah (February 26, 1913) |

|||

The following states have not ratified the amendment: |

|||

# Alabama |

|||

# Kentucky |

|||

# Mississippi |

|||

# Virginia |

|||

# South Carolina |

|||

# Georgia |

|||

# Maryland |

|||

# Delaware |

|||

# Rhode Island |

|||

# Florida |

|||

==Calls for repeal== |

==Calls for repeal== |

||

Revision as of 18:39, 5 December 2008

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2008) |

The Seventeenth Amendment (Amendment XVII) to the United States Constitution passed the Senate on June 12, 1911 and the House of Representatives on May 13, 1912. The states completed ratification on April 8, 1913. The amendment specifically changed Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution to the extent the amendment provides for the direct, popular election of U.S. Senators by the people of the state they represent, rather than that state's legislature electing or appointing its two Senators. It also provided a new contingency provision which enabled a state's governor or executive authority, if so authorized by that state's legislature, to appoint a Senator in the event of a Senate vacancy, until an election could be held to fill the vacancy.

Text

The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State, elected by the people thereof, for six years; and each Senator shall have one vote. The electors in each State shall have the qualifications requisite for electors of the most numerous branch of the State legislatures.

When vacancies happen in the representation of any State in the Senate, the executive authority of each State shall issue writs of election to fill such vacancies: Provided, That the legislature of any State may empower the executive thereof to make temporary appointments until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct.

This amendment shall not be so construed as to affect the election or term of any Senator chosen before it becomes valid as part of the Constitution.

Historical background

The selection of delegates to the Constitutional Convention established the precedent that states could choose Federal officials at a higher level than direct election. Originally, each Senator was to be elected by his state legislature to represent his state, providing one of the many necessary American governmental checks and balances. The delegates to the Convention also expected a Senator elected by his state's legislature would be able to concentrate on the governmental business at hand without direct, immediate pressure from the populace of his state, also aided by a longer term (six years) than the one afforded to members of the House of Representatives (two years).

This process worked without major problems through the mid-1850s, when the American Civil War was in the offing. Due to increasing partisanship and strife, many state legislatures failed to elect Senators for prolonged periods. For example, in Indiana the conflict between Democrats in the southern half of the state and the emerging Republican Party in the northern half prevented a Senatorial election for two years. The aforementioned partisanship led to contentious battles in the legislatures, as the struggle to elect Senators reflected the increasing regional tensions in the lead up to the Civil War.

After the Civil War, the problems multiplied. In one case in the mid-1860s, the election of Senator John P. Stockton from New Jersey was contested on the grounds that he had been elected by a plurality rather than a majority in the state legislature.[1] Stockton defended himself on the grounds that the exact method for elections was murky and varied from state to state. To keep this from happening again, Congress passed a law in 1866 regulating how and when Senators were to be elected from each state. This was the first change in the process of senatorial elections. While the law helped, there were still deadlocks in some legislatures and accusations of bribery, corruption, and suspicious dealings in some elections. Nine bribery cases were brought before the Senate between 1866 and 1906, and 45 deadlocks occurred in 20 states between 1891 and 1905, resulting in numerous delays in seating Senators. Beginning in 1899, Delaware did not send a senator to Washington for four years.

Reform efforts began as early as 1826, when direct election was first proposed. In the 1870s, voters sent a petition to the House of Representatives for popular election. From 1893 to 1902, the popularity of this idea increased considerably. Each year during that period, a Constitutional amendment to elect Senators by popular vote was proposed in Congress, but the Senate resisted greatly. In the mid-1890s, the Populist Party incorporated the direct election of Senators into its platform, although neither the Democratic Party nor the Republican Party paid much notice at the time. Direct election was also part of the Wisconsin Idea championed by the Republican progressive Robert M. La Follette, Sr. and the Nebraskan Republican reformer George W. Norris. In the early 1900s, Oregon pioneered direct election of Senators, and it experimented with different measures over several years until success in 1907. Soon thereafter, Nebraska followed suit, and it laid the foundation for other states to adopt measures for direct election of Senators.

After the turn of the century, support of Senatorial election reform grew rapidly. William Randolph Hearst expanded his publishing empire with Cosmopolitan, which became a respected general-interest magazine at that time, and which championed the cause of direct election with muckraking articles and strong advocacy of reform. Hearst hired a veteran reporter, David Graham Phillips, who wrote scathing pieces on Senators, portraying them as corrupt pawns of industrialists and financiers. The pieces became a series titled "The Treason of the Senate," which appeared in several monthly issues of the magazine in 1906.[2]

Increasingly, Senators were elected based on state referenda, similar to the means developed by Oregon. By 1912, as many as 29 states elected Senators either as nominees of party primaries, or in conjunction with a general election. As representatives of a direct election process, the new Senators supported measures that argued for new legislation, but in order to achieve total election reform, a Constitutional amendment was required. In 1911, Senator Joseph L. Bristow from Kansas offered a resolution, proposing an amendment. The notion enjoyed strong support from Senator William Borah of Idaho, himself a product of direct election. Eight Southern Senators and all of the Republican Senators from New England, New York, and Pennsylvania opposed Bristow's resolution. Nevertheless, the Senate approved the resolution largely because of the Senators who had been elected by state-initiated reforms, many of whom were serving their first terms, and therefore were more willing to support direct election. After the Senate passed the Amendment resolution, the measure moved to the House of Representatives.

The House initially had fared no better than the Senate in its early discussions of the proposed Amendment. During the summer of 1912, the House finally passed the amendment and sent it to the States for ratification. The campaign for public support was aided by Senators such as Senator Borah and the political scientist George H. Haynes, whose scholarly work on the Senate contributed to passage of the amendment.[1]

The final State needed to ratify the Amendment was Connecticut, which ratified it on April 8, 1913, a year and a half prior to the 1914 Senate election.

Effect

The Seventeenth Amendment restates the first paragraph of Article I, § 3 of the Constitution and provides for the election of Senators by replacing the phrase "chosen by the Legislature thereof" with "elected by the people thereof." Also, it allows the Governor of each state, if authorized by that state's legislature, to appoint a Senator in the event of an opening, until an election occurs.

The Seventeenth Amendment did not affect the restriction in Article I, § 4, cl. 1, which prohibits the Congress from exercising a power to "make or alter" state regulations of elections in order to determine where Senators must be chosen. When the State Legislatures chose the Senators, allowing the Congress to regulate the "places of choosing Senators" would have allowed the Congress to essentially stipulate where the State's Legislature had to meet, at least for the purposes of choosing its Senators, which would have been inconsistent with State sovereignty.

However, the Amendment does state that all citizens eligible to vote for the election of the "most numerous house of the State legislature" shall be eligible to vote for the U. S. Senator. In a way, this is a bit odd, since the most numerous house is usually the State House of Represetatives (or the same body with a different name). However, the intent was to open up the election for the U. S. Senate to the widest number of voters possible. However, in practical applications, this point is moot because the qualifications to vote for either the State Senate or the State House of Representatives are equal in almost all cases. In addition, recall that Nebraska has a Legislature that consists of just one chamber, which is called the State Senate in this case.

Direct elections held in the states

From United States Congressional Elections, 1788-1997, The Official Results by Michael J. Dubin

|

|

|

Since the seating of the Sixty-Sixth Congress in 1919, every Senator had been chosen by a direct popular vote, rather than by the State legislatures.

The new States of Arizona, Alaska, and Hawaii are the only states never to have elected U.S. Senators under the original design of the Constitution. Oklahoma (1907) and New Mexico (1912), two other new states, apparently only elected U.S. Senators by the Legislature once.

==mjghdnmdhgn

Calls for repeal

Several states' rights advocates have called for the Seventeenth Amendment's repeal.[3] For example, former U.S. Senator Zell Miller of Georgia, shortly after announcing his intention to retire from the Senate, made this statement:

Direct elections of Senators … allowed Washington’s special interests to call the shots, whether it is filling judicial vacancies, passing laws, or issuing regulations.[4]

Thomas DiLorenzo, author of The Real Lincoln: A New Look at Abraham Lincoln, His Agenda, and an Unnecessary War, wrote:

The Seventeenth Amendment was one of the last nails to be pounded into the coffin of federalism in America.[5]

Some critics of the amendment blame it, together with the Sixteenth Amendment, for the general expansion of the authority of the United States Congress in the 20th century.[6]

Notes

References

Note: Much of the text of this article appears to come from the above page, which is in the public domain as a work of the United States government.

- NARA - The National Archives Experience: Seventeenth Amendment

- From: Mrs. Lawrence's History Notes (Frost Middle School- 7GTC Discovery Team)

- The Road to Mass Democracy: Original Intent and the Seventeenth Amendment, Christopher Hyde Hoebeke

- Bybee, Jay S. (1997). "Ulysses at the Mast: Democracy, Federalism, and the Sirens' Song of the Seventeenth Amendment". Northwestern University Law Review. 91. Chicago, IL: Northwestern University Law Review: 505.