Ras al-Ayn

Ras al-Ayn

Serê Kaniyê راس العين | |

|---|---|

Serê Kaniyê | |

| Coordinates: 36°51′01″N 40°04′14″E / 36.8503°N 40.0706°E | |

| Country | Syria |

| Governorate | al-Hasakah |

| District | Ras al-Ayn |

| Subdistrict | Ras al-Ayn |

| Control | |

| Elevation | 360 m (1,180 ft) |

| Population (2004)[1] | 29,347 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Area code | +963 52 |

| Geocode | C4988 |

Ras al-Ayn (Arabic: رَأْس ٱلْعَيْن, romanized: Raʾs al-ʿAyn, Kurdish: سەرێ کانیێ, romanized: Serê Kaniyê, Classical Syriac: ܪܝܫ ܥܝܢܐ, romanized: Rēš Aynā[2]), also spelled Ras al-Ain, is a city in al-Hasakah Governorate in northeastern Syria, on the Syria–Turkey border.

One of the oldest cities in Upper Mesopotamia, the area of Ras al-Ayn has been inhabited since at least the Neolithic age (c. 8,000 BC). Later known as the ancient Aramean city of Sikkan, the Roman city of Rhesaina, and the Byzantine city of Theodosiopolis, the town was destroyed and rebuilt several times, and in medieval times was the site of fierce battles between several Muslim dynasties. With the 1921 Treaty of Ankara, Ras al-Ayn became a divided city when its northern part, today's Ceylanpınar, was ceded to Turkey.

With a population of 29,347 (as of 2004[update]),[1] it is the third largest city in al-Hasakah Governorate, and the administrative center of Ras al-Ayn District.

During the civil war, the city became contested between Syrian opposition forces and YPG from November 2012 until it was finally captured by the YPG in July 2013. It was later captured by the Turkish Armed Forces and the Syrian National Army during the 2019 Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria.[3][4][5][6]

Etymology

[edit]The first mention of the town is in Akkadian Rēš ina[7] during the reign of the Assyrian king Adad-nirari II (911-891 BC).[7] The Arabic name Ras al-Ayn is a literal translation of the Akkadian name and has the same meaning; "head of the spring",[7] or idiomatically, "hill of the spring", indicating a prominent mountain formation close to a well.

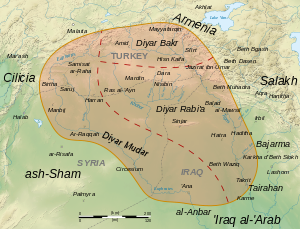

The ancient Greek geographer Ptolemy (d. 168) names the town Raisena.[8] The town, as part of the Roman Empire, was called Ressaina/Resaina.[9] Another name was Theodosiopolis, after emperor Theodosius I, who enlarged the town in 380.[8] The 11th century Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi visited the town, mentioning its name as Ras al-'Ayn, and assigning it to Diyar Rabi'a (abode of the Arab tribe Rabi'a). He also described it as a big city with plenty of water, around 300 springs from which most of al-Khabur river starts.[10] In addition to Ras al-Ayn, medieval Arab Muslim sources refer to the town sometimes as Ain Werda.[8] Nineteenth-century English sources refer to the town as Ras Ain, Ain Verdeh (1819),[11] or Ras el Ain (1868).[8] The Kurdish name Serê Kaniyê also means "head of the spring" or "head of the fountain", referring to water source areas. This name is probably a modern literal translation of the ancient Semitic name.[citation needed]

Geography

[edit]This section needs expansion with: about everything missing. You can help by adding to it. (November 2015) |

Ras al-Ayn is located in the Upper Khabur basin in the northern Syrian region of Jazira. The Khabur, largest tributary of the Euphrates, crosses the border from Turkey near the town of Tell Halaf, about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) to the southwest of the city. The overground feeders, originating on the headwaters of the Karaca volcano in Şanlıurfa Province, usually do not carry water in the summer, even though Turkey brings in water from the Atatürk reservoir to irrigate the region of Ceylanpınar. While more than 80% of the Upper Khabur's water originates in Turkey, this mostly comes as underground flow.[12] So rather than the overground streams, it is the giant karstic springs of the Ras al-Ayn area that is considered the river's main perennial source.[13]

Ras al-Ayn springs

[edit]Ras al-Ayn has more than 100 natural springs. The most famous spring is Nab'a al-Kebreet, a hot spring with a very high mineral content, containing calcium, lithium, and radium.

Water supply

[edit]The Allouk water pumping station, which distributes water to the Hasakah Governorate, is close to Ras al-Ayn. Since the Turkish occupation began, the water supply has been interrupted several times.[14] Previously, the station supplied about 460,000 people in Al-Hasakah, Tell Tamer, and the Al-Hawl refugee camp, but not since the last interruption in March 2020, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.[15]

History

[edit]This section needs expansion with: missing epochs of the city's history. You can help by adding to it. (November 2015) |

Oriental Institute Museum, Chicago, USA.

Neolithic and ancient history

[edit]The area of Ras al-Ayn was inhabited at least since the Neolithic age (c. 8.000 BC). Today's Ras al-Ayn can be traced back to a settlement existing since c. 2000 BC, which in the early 1st millennium BC became the ancient city of Sikkan, part of the Aramaean kingdom of Bit Bahiani. The archaeological site is located on the southern edge of the mound Tell Fekheriye, around which today's Ras al-Ayn is built, just a few hundred meters south of the city center. During excavations in 1979, the famous Tell Fekheriye bilingual inscription was found. The nearby town of Tell Halaf is also a former site of an Aramean city.

Classical era

[edit]In later times, the town became known as "Rhesaina", "Ayn Warda", and "Theodosiopolis", the latter named after the Byzantine emperor Theodosius I who granted the settlement city rights. The latter name was also shared with the Armenian city of Karin (modern Erzurum) making it difficult to distinguish between them.[16]

The Sasanians destroyed the city twice in 578 and 580 before rebuilding it and constructing one of the three Sassanian academies in it (the other two being Gundishapur and Ctesiphon) in it.

Medieval history

[edit]The city fell to the Arabs in 640 who confiscated parts of the city which were abandoned by their inhabitants.[16] The Byzantines raided the city in 942 and took many prisoners. In 1129, Crusader Joscelin I managed to hold the city briefly, killing many of its Arab inhabitants.[16]

At its height the city had a West Syrian bishopric and many monasteries. The city also contained two mosques and an East Syrian church and numerous schools, baths, and gardens.[16]

Ras al-Ayn became contested between the Zengids, Ayyubids, and the Khwarazmians in the 12th and 13th centuries. It was sacked by Tamerlane at the end of the 14th century, ending its role as a major city in al-Jazira.[16]

Ottoman history

[edit]In the 19th century a colony of Muslim Chechen refugees fleeing the Russian conquest of the Caucasus were settled in the town by the Ottoman Empire.[8] The Ottomans also built barracks and a fort for a thousand soldiers to control and protect the refugees.[8]

During the Armenian genocide, Ras al-Ayn was one of the major collecting points for deported Armenians. From 1915 on, 1.5 million Armenians were deported from all over Anatolia, many forced on death marches into the Syrian desert.[17] Approximately 80,000 Armenians, mostly women and children, were slaughtered in desert death camps near Ras al-Ayn.[18] As well as the Deir ez-Zor Camps further south, the Ras al-Ayn Camps became "synonymous with Armenian suffering."[19]

Modern history

[edit]After the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the 1921 Treaty of Ankara, Ras al-Ayn became a divided city when its northern neighborhoods, today's Ceylanpınar, were ceded to Turkey. Today, the two cities are separated by a fenced border strip and the Berlin–Baghdad Railway on the Turkish side. The only border crossing is located in the western outskirts of Ras al-Ayn. The town was first part of the French colonial empire's Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon and, from 1946, the independent state of Syria.

Civil War

[edit]During the civil war, Ras al-Ayn was engulfed by the long Battle of Ras al-Ayn. In late November 2012, rebels of al-Nusra Front and the FSA attacked Syrian Army positions, expelling them from the town. During the following eight months, the Kurdish-majority People's Protection Units (YPG), present from the outset, gradually entrenched its position, and eventually formed an alliance with a non-jihadist FSA faction. On 21 July 2013, this alliance expelled the jihadists after a night of heavy fighting.

The town was part of Rojava for the following six years, until it was attacked and captured by the Turkish army and allied Syrian National Army during the October 2019 Turkish offensive into north-eastern Syria, in the Second Battle of Ras al-Ayn.[20][4] After 11 days of clashes and siege, the Syrian Democratic Forces and the Kurdish YPG retreated from Ras al-Ayn as part of a ceasefire agreement.[21]

Bombings

[edit]On December 10, 2020, a car bomb exploded at a checkpoint run by Turkish-supported Syrian National Army rebels in Ras al-Ayn.[22] Reports on casualties differed, but according to several sources the explosion killed over 10 people including 2 Turkish soldiers.[23][22][24] Turkish authorities blamed the Peoples Protection Units (YPG) for the car bombing as Turkey claims they are affiliated with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).[25][26] According the ABC, no group has claimed responsibility for the bombing.[23]

Bombing continued in January and February 2021.[27][28]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 14,278 | — |

| 2004 | 29,347 | +105.5% |

In 2004 the population was 29,347.[1] The town has been described as having an Arab majority,[29][30] in addition to Kurdish, Assyrian, Armenian, Turkmen and Chechen minorities before the Turkish/SNA takeover in October 2019.[31] War crimes committed since the Turkish occupation began have since caused an exodus of Kurds, Christians, and other minorities from the town such as Assyrians and Armenians.[32] The Turkish government's resettling of mainly Arab and Turkmen Syrian refugees from other parts of Syria in Ras al-Ayn has further altered the town's demographics.[32][33]

Churches in the town

[edit]- Syriac Orthodox Church of Saint Thomas the Apostle (كنيسة مار توما الرسول للسريان الأرثوذكس)

- Syriac Catholic Church of Mary Magdalene (كنيسة مريم المجدلية للسريان الكاثوليك)

- Armenian Orthodox Church of Saint Hagop (كنيسة القديس هاكوب للارمن الارثوذكس)

-

People in the city center

-

Orthodox church

-

A view in October 2013. The city fell under YPG control during the Syrian Civil War

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "2004 Census Data for Nahiya Ras al-Ayn" (in Arabic). Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics. Also available in English: UN OCHA. "2004 Census Data". Humanitarian Data Exchange.

- ^ Thomas A. Carlson et al., “Reshʿayna — ܪܝܫ ܥܝܢܐ ” in The Syriac Gazetteer last modified December 9, 2016, http://syriaca.org/place/172.

- ^ "Kurdish-led fighters battle pro-Turkish forces for control of key border town". Middle East Eye. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ a b "Turkey claims capture of key Syrian border town as offensive continues". NBC News. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ "8 days of Operation "Peace Spring": Turkey controls 68 areas, "Ras al-Ain" under siege, and 416 dead among the SDF, Turkish forces and Turkish-backed factions • The Syrian Observatory For Human Rights". October 17, 2019.

- ^ "Turkish army takes control over Syrian border city of Ras al-Ayn - TV". TASS.

- ^ a b c Dominik Bonatz (1 April 2014). The Archaeology of Political Spaces: The Upper Mesopotamian Piedmont in the Second Millennium BCE. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 61–. ISBN 978-3-11-026640-5.

- ^ a b c d e f Taylor, John George (1868). "Journal of a Tour in Armenia, Kurdistan and Upper Mesopotamia, with Notes of Researches in the Deyrsim Dagh, in 1866". In Royal Geographical Society (ed.). The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society. London. pp. 281–360, here: 346–350.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ J. B. Bury (18 July 2012). History of the Later Roman Empire. Courier Corporation. pp. 94–. ISBN 978-0-486-14338-5.

- ^ Muhammad al-Idrisi (1154). نزهة المشتاق في اختراق الآفاق: Or, Tabula Rogeriana. عالم الكتب. pp. vol. 2, 661.

- ^ Abraham Rees (1819). The Cyclopædia: Or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature. Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown. pp. 449–.

- ^ Greg Shapland (1997). "The Tigris–Euphrates Basin". Rivers of Discord: International Water Disputes in the Middle East. London: Hurst & Company. pp. 103–143, here: 127. ISBN 1-85065-214-7.

- ^ John F. Kolars; William A. Mitchell (1991). "A critical pressure point: The Ceylanpinar/Ras al-Ayn Area". The Euphrates River and the Southeast Anatolia Development Project. Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press. p. 222. ISBN 0-8093-1572-6.

- ^ "Turkish-backed group's disruption of water puts 460,000 people at risk, UNICEF warns". www.kurdistan24.net. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

- ^ "Interruption to key water station in the northeast of Syria puts 460,000 people at risk as efforts ramp up to prevent the spread of Coronavirus disease". www.unicef.org. Retrieved 2020-03-24.

- ^ a b c d e Gibb, Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen (1995). The Encyclopaedia of Islam: NED-SAM. Brill. pp. 433 f.

- ^ "Armenian genocide survivors' stories: 'My dreams cannot mourn'". the Guardian. April 24, 2015.

- ^ Sondhaus, Lawrence (2011). World War One: The Global Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 390. ISBN 978-0-521-51648-8.

- ^ Jones, Adam (2006). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction (PDF). Routledge/Taylor & Francis. p. 110. ISBN 0-415-35385-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-10. Retrieved 2015-11-10.

- ^ "Turkey claims capture of key Syrian border town". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 2023-07-05.

- ^ "Kurdish forces depart border city of Ras al-Ayn as part of cease-fire with Turkey". The Washington Post. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Car bomb kills at least four in Turkish-controlled north Syria". Reuters. 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- ^ a b "Car bomb in Syrian city kills 2 Turkish soldiers, 2 locals". ABC News. Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- ^ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "16 Menschen sterben bei Anschlag in Syrien | DW | 10.12.2020". DW.COM (in German). Retrieved 2021-04-04.

- ^ Fox, Tessa. "Civilians flee Ain Issa, northeast Syria as clashes escalate". www.aljazeera.com.

- ^ "Car bomb explosion kills 11 in rebel-held area in NE Syria - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com.

- ^ Musa, Esref; Koparan, Omer; Karaahmet, Ahmet; Misto, Mohamad; Ozcan, Ethem Emre (2 January 2021). "4 civilians dead, 37 injured in Syria bomb blasts". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ Musa, Esref; Ozcan, Ethem Emre (3 March 2021). "Twin blasts hit northern Syrian district of Ras al-Ayn". www.aa.com.tr. Retrieved 23 November 2022.

- ^ "Christians Killed on Syria's Front Lines". Christianity Today.

- ^ "How will Syrian border towns react to Turkey's Operation Peace Spring?". Arab News. 10 October 2019.

- ^ "Subscribe to The Australian | Newspaper home delivery, website, iPad, iPhone & Android apps". www.theaustralian.com.au.

Mohammed Rwanduzy. "Turkish-backed groups continue looting, lawlessness in Sari Kani". Rudaw.

David Enders. "Rebels capture Ras al Ayn, 1st town to fall in Syria's Kurdish region". Mcclatchy DC.

"US, Allied Kurdish Force Conduct Patrol on Syrian Border". Asharq AL-awsat.

"Turkish army captures key Kurdish city in Syria's Hasakah - Xinhua | English.news.cn". www.xinhuanet.com. - ^ a b "Inside the ethnic cleansing of Turkey's Syrian 'safe zone'". The Independent. May 16, 2020.

"Turks and jihadists in 'soft' ethnic cleansing of Kurds and Christians in North East Syria". www.asianews.it.

Ensor, Josie (November 17, 2019). "Kurds watch their homes burn from afar as picture of 'ethnic cleansing' emerges". The Telegraph – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

"Ethnic cleansing already taking place in Turkey's Syrian safe zone - Independent". Ahval. - ^ "Majority of refugees forced to return to Turkey's Syria safe zone - report". Ahval.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Ras al-Ayn, al-Hasakah Governorate at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ras al-Ayn, al-Hasakah Governorate at Wikimedia Commons