Bowling Green, Ohio

Bowling Green, Ohio | |

|---|---|

Downtown Bowling Green, Ohio as seen from the intersection of Main St. and Wooster St. | |

| Nicknames: BG, Pull Town, USA | |

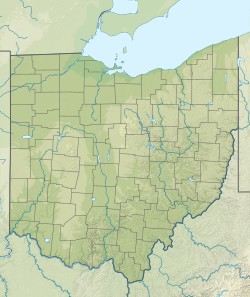

Location of Bowling Green in Wood County | |

| Coordinates: 41°22′26″N 83°39′03″W / 41.37389°N 83.65083°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Wood |

| Incorporated | 1901[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | "Mayor-Administrator"[2] |

| • Mayor | Mike Aspacher[3] |

| • Municipal Administrator | Lori Tretter[4] |

| Area | |

• Total | 12.91 sq mi (33.44 km2) |

| • Land | 12.86 sq mi (33.32 km2) |

| • Water | 0.05 sq mi (0.12 km2) 0.40% |

| Elevation | 689 ft (210 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 30,808 |

• Estimate (2023)[7] | 30,384 |

| • Density | 2,395.09/sq mi (924.72/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| Zip code | 43402 & 43403 |

| Area code(s) | 419, 567 |

| FIPS code | 39-07972[8] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1087179[6] |

| Website | https://www.bgohio.org |

Bowling Green is a city in and the county seat of Wood County, Ohio, United States,[9] located 20 miles (32 km) southwest of Toledo. The population was 30,808 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Toledo metropolitan area and a member of the Toledo Metropolitan Area Council of Governments.[10] Bowling Green is the home of Bowling Green State University.

History

[edit]Settlement

[edit]Bowling Green was first settled in 1832, was incorporated as a town in 1855, and became a city in 1901. The village was named after Bowling Green, Kentucky, by a retired postal worker who had once delivered mail there.[11][12]

Growth and oil boom

[edit]In 1868 Bowling Green was designated as the county seat, succeeding Perrysburg.[13]

With the discovery of oil in the area in the late 19th and early 20th century, Bowling Green enjoyed a boom to its economy. The results of wealth generated at the time can still be seen in the downtown storefronts, and along Wooster Street, where many of the oldest and largest homes were built.[14] A new county courthouse was also constructed in the 1890s. The Neoclassical US post office was erected in 1913.[15]

Industrialization

[edit]This period was followed by an expansion of the automobile industry. In late 1922 or early 1923, Coats Steam Car moved to the area and hired numerous workers. It eventually went out of business as the industry became centralized in Detroit, Michigan.

Bank robbers Pretty Boy Floyd and Billy the Killer encountered police in Bowling Green in April 1931. Their armed confrontation resulted in the death of Billy the Killer.[16]

During World War II Italian and German prisoners of war were held nearby. They were used to staff the Heinz Tomato Ketchup factory in town.[17] The ketchup factory closed in 1975.[18]

A runaway freight train carrying hazardous liquids passed through Bowling Green in 2001, in what is known as the known as the CSX 8888 incident. It traveled more than 65 miles south of Toledo before being stopped by a veteran railroad worker near Kenton; he jumped into the train while it was moving. No one was hurt and there was no property damage in the incident.[19]

Geography

[edit]According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 12.61 square miles (32.66 km2), of which 12.56 square miles (32.53 km2) is land and 0.05 square miles (0.13 km2) is water.[20] Bowling Green is within an area of land that was once the Great Black Swamp which was drained and settled in the 19th century. The nutrient-rich soil makes for highly productive farm land. Bowling Green, Ohio is in the North Western hemisphere at approximately 41.376132°N, -83.623897°W.

Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Bowling Green, Ohio, 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

74 (23) |

85 (29) |

91 (33) |

97 (36) |

104 (40) |

110 (43) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

91 (33) |

82 (28) |

70 (21) |

110 (43) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 55.3 (12.9) |

57.0 (13.9) |

69.1 (20.6) |

79.6 (26.4) |

87.4 (30.8) |

93.7 (34.3) |

93.8 (34.3) |

92.4 (33.6) |

90.1 (32.3) |

82.7 (28.2) |

68.7 (20.4) |

58.5 (14.7) |

95.6 (35.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 32.6 (0.3) |

35.7 (2.1) |

46.0 (7.8) |

59.5 (15.3) |

71.2 (21.8) |

80.7 (27.1) |

84.2 (29.0) |

82.1 (27.8) |

76.3 (24.6) |

63.5 (17.5) |

49.5 (9.7) |

37.8 (3.2) |

59.9 (15.5) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 25.9 (−3.4) |

28.4 (−2.0) |

37.3 (2.9) |

49.0 (9.4) |

60.8 (16.0) |

70.7 (21.5) |

74.0 (23.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

65.3 (18.5) |

53.6 (12.0) |

41.4 (5.2) |

31.4 (−0.3) |

50.8 (10.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 19.2 (−7.1) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

38.5 (3.6) |

50.3 (10.2) |

60.8 (16.0) |

63.8 (17.7) |

61.8 (16.6) |

54.3 (12.4) |

43.6 (6.4) |

33.4 (0.8) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

41.7 (5.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −1.8 (−18.8) |

3.2 (−16.0) |

11.4 (−11.4) |

24.4 (−4.2) |

36.2 (2.3) |

46.9 (8.3) |

52.8 (11.6) |

51.1 (10.6) |

41.0 (5.0) |

30.0 (−1.1) |

18.6 (−7.4) |

7.0 (−13.9) |

−4.6 (−20.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−22 (−30) |

−7 (−22) |

8 (−13) |

25 (−4) |

32 (0) |

41 (5) |

35 (2) |

25 (−4) |

13 (−11) |

0 (−18) |

−20 (−29) |

−22 (−30) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.26 (57) |

2.01 (51) |

2.21 (56) |

3.40 (86) |

3.99 (101) |

3.60 (91) |

3.53 (90) |

3.79 (96) |

2.91 (74) |

2.83 (72) |

2.37 (60) |

2.26 (57) |

35.16 (891) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 6.3 (16) |

6.1 (15) |

2.6 (6.6) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.5 (1.3) |

5.3 (13) |

21.3 (53.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.1 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 9.8 | 10.3 | 9.4 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.3 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 7.7 | 98.4 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 4.1 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 2.4 | 12.5 |

| Source 1: NOAA[21] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: National Weather Service[22] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 906 | — | |

| 1880 | 1,539 | 69.9% | |

| 1890 | 3,467 | 125.3% | |

| 1900 | 5,067 | 46.1% | |

| 1910 | 5,222 | 3.1% | |

| 1920 | 5,788 | 10.8% | |

| 1930 | 6,688 | 15.5% | |

| 1940 | 7,190 | 7.5% | |

| 1950 | 12,005 | 67.0% | |

| 1960 | 13,574 | 13.1% | |

| 1970 | 21,760 | 60.3% | |

| 1980 | 25,745 | 18.3% | |

| 1990 | 28,176 | 9.4% | |

| 2000 | 29,636 | 5.2% | |

| 2010 | 30,028 | 1.3% | |

| 2020 | 30,808 | 2.6% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 30,384 | [7] | −1.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[23][24] | |||

2010 census

[edit]As of the census[25] of 2010, there were 30,028 people, 11,288 households, and 4,675 families living in the city. The population density was 2,390.8 inhabitants per square mile (923.1/km2). There were 12,301 housing units at an average density of 979.4 per square mile (378.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 87.6% White, 6.4% African American, 0.2% Native American, 2.1% Asian, 1.4% from other races, and 2.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.8% of the population.[26]

There were 11,288 households, of which 18.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 30.7% were married couples living together, 7.5% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.2% had a male householder with no wife present, and 58.6% were non-families. 35.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 7.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.16 and the average family size was 2.82.[27]

The median age in the city was 23.2 years. 12.8% of residents were under the age of 18; 43.2% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 19.5% were from 25 to 44; 15.7% were from 45 to 64; and 8.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.0% male and 52.0% female.[citation needed]

2000 census

[edit]As of the census[8] of 2000, there were 29,636 people, 10,266 households, and 4,434 families living in the city. The population density was 2,919 inhabitants per square mile (1,127.0/km2). There were 10,667 housing units at an average density of 1,050.6 per square mile (405.6/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 91.84% White, 2.82% African American, 0.21% Native American, 1.83% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 1.81% from other races, and 1.46% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.48% of the population.[citation needed]

There were 10,266 households, out of which 20.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 33.2% were married couples living together, 7.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 56.8% were non-families. 34.3% of all households were people living alone, including 7.0% who were 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.21, and the average family size was 2.84.[citation needed]

In the city, the population was spread out, with 13.1% under the age of 18, 46.6% from 18 to 24, 19.5% from 25 to 44, 13.2% from 45 to 64, and 7.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 22 years. For every 100 females, there were 87.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 85.4 males.[citation needed]

The median income for a household in the city was $30,599, and the median income for a family was $51,804. Males had a median income of $33,619 versus $25,364 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,032. About 8.0% of families and 25.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.8% of those under age 18 and 4.8% of those age 65 or over.[citation needed]

Economy

[edit]

Lubrizol maintains a soap and surfactant production plant in Bowling Green.[28][29] The Bowling Green plant opened in 1994 and was expanded in 2013.[30]

Energy policy

[edit]

Ohio's first utility-sized wind farm is located along U.S. Route 6 just west of the city limits.[31] There are four turbines that are each 257 feet (78 m) tall. These turbines generate up to 7.2 megawatts of power, which is enough to supply electricity for some 3,000 residents. Located about six miles (10 km) from the city, the turbines can be seen for miles and have become a local attraction.[32] At the site of the turbines, a solar-powered kiosk provides information for visitors, including current information on wind speeds and the amount of energy being produced by the turbines.

Culture

[edit]The Black Swamp Arts Festival is a free arts and live music festival held the first full weekend after Labor Day. Its mission is to "connect art and the community by presenting an annual arts festival and by promoting the arts in the Bowling Green community."[33]

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary

[edit]Public elementary schools of the Bowling Green City School District include Kenwood Elementary, Conneaut Elementary and Crim Elementary.[34] Ridge Elementary was closed in 2013[35][36] and Milton Elementary was closed in 2011.[36] Two private primary schools, Bowling Green Christian Academy and the Montessori School of Bowling Green, and one parochial, St. Aloysius, also call Bowling Green home. The Bowling Green Early Childhood Learning Center (Montessori) offers kindergarten and Plan, Do and Talk goes up to grade three.

Secondary schools include Bowling Green Middle School and Bowling Green Senior High School.

Post-secondary

[edit]Bowling Green State University is located on the northeast side of the city, along and north of Wooster Street (Ohio State Route 64, Ohio State Route 105). As of September 2020, it has 20,232 students.[37]

Library

[edit]

Bowling Green has the main branch of the Wood County District Public Library.[38]

Media

[edit]Newspapers

[edit]Radio

[edit]Television

[edit]Transportation

[edit]

A public demand response bus service is operated by the city through B.G. Transit.[39] Bowling Green State University offers shuttle services via its own buses with routes throughout campus and the downtown area.[40]

Bowling Green is linked to North Baltimore via a 13-mile (21 km) rail trail called the Slippery Elm Trail,[41] with East Broadway Street in North Baltimore on the south end and Sand Ridge Road in Bowling Green on the north end.[42] A CSX line runs through town.

Notable people

[edit]- John Barnes, science-fiction writer[43]

- Alissa Czisny, figure skater, 2009 and 2011 U.S. champion

- Anthony De La Torre, actor

- William Easterly, economist / professor at NYU

- Randy Gardner, Chancellor, Ohio Department of Higher Education

- Theresa Gavarone, Ohio Senator

- Scott Hamilton, figure skater, 1984 Olympic champion; television commentator

- Chris Hoiles, retired Major League Baseball player

- Doug Mallory, NFL assistant coach

- Mike Mallory, NFL assistant coach

- Howard McCord poet, novelist, writing professor

- Paul Pope, alternative comic book writer/artist

- Andy Tracy, first baseman for the Philadelphia Phillies

- Dave Wottle, runner, 1972 Olympic gold medalist in the 800m

- Cara Zavaleta, reality TV personality and model

References

[edit]- ^ "City of Bowling Green". Archived from the original on December 20, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2006. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ^ "The City of Bowling Green, Ohio". Archived from the original on December 20, 2005. Retrieved December 31, 2006.

- ^ "Mayor Mike Aspacher". bgohio.org. City of Bowling Green Ohio. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ "Municipal Administrator". www.bgohio.org. City of Bowling Green Ohio. Archived from the original on March 3, 2022. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Bowling Green, Ohio

- ^ a b "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places in Ohio: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "TOLEDO METROPOLITAN AREA COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS MEMBERSHIP" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ^ Overman, William Daniel (1958). Ohio Town Names. Akron, OH: Atlantic Press. p. 17.

- ^ Overman, James (January 1967). "The History of Bowling Green State University". Bgsu Faculty Books: 16. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "Dinner celebrates Wood County history". Sentinel-Tribune. Archived from the original on February 7, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- ^ "Early History of Bowling Green, Ohio". Archived from the original on December 14, 2011.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ McLaughlin, Jan Larson. "Wood County had its share of murders & robberies in 'wild west' past – BG Independent News". Retrieved November 11, 2019.

- ^ "Bee Gee News June 15, 1944". BG News (Student Newspaper). June 15, 1944. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ "The BG News April 2, 1975". BG News (Student Newspaper). April 2, 1975. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ Claiborne, William; Phillips, Don (May 16, 2001). "Railroad Worker Jumps Into, Stops Runaway Train". Washington Post. Retrieved November 12, 2019.

- ^ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ "U.S. Climate Normals Quick Access – Station: Bowling Green WWTP, OH". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "NOAA Online Weather Data – NWS Cleveland". National Weather Service. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Bowling Green city, Ohio". Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "American FactFinder - Results". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ "Quick Facts". United States Census Bureau. United States. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010". American FactFinder. United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ "Lubrizol to expand its B.G. plant". Toledo Blade. Retrieved November 25, 2019.

- ^ "Tensions Surface". HAPPI. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Lubrizol to expand its B.G. plant". Toledo Blade. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Ohio's First Commercial Wind Farm". Green Energy Ohio. Archived from the original on November 10, 2007. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ "Ohio gov blows hard with wind-powered energy". Environment Ohio. January 12, 2008. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ "About". blackswampfest.org. Black Swamp Arts Festival. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ "Bowling Green City Schools :: Schools". Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ Alusheff, Alex (October 7, 2013). "Bowling Green City Council buys Ridge Elementary to convert to park". The BG News. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ a b Rice, Laura (May 17, 2011). "BG City Schools to close two schools, cut no teachers". North West Ohio. Archived from the original on March 5, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ "BGSU announces record retention, highest enrollment in more than a decade". Bowling Green State University. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Hours & Locations". Wood County District Public Library. Archived from the original on March 3, 2018. Retrieved March 3, 2018.

- ^ "Public Transportation". Archived from the original on August 14, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ "Shuttle Routes". Bowling Green State University. Archived from the original on September 7, 2017. Retrieved December 8, 2018.

- ^ "[Wood County Park District]". www.wcparks.org. Archived from the original on March 1, 2014.

- ^ "Wood County Park District". Archived from the original on March 1, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2014.

- ^ "Foreword," in Barnes, John. Apostrophes and Apocalypses. NYC:Tor 1998 p. 9