Sellafield: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Sellafield''' (formerly known as '''Windscale''') is a nuclear processing and former electricity generating site, |

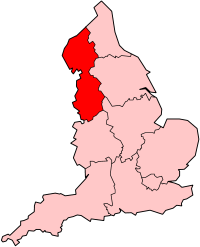

'''Sellafield''' (formerly known as '''Windscale''') is a nuclear processing and former electricity generating site, closed to the village of [[Seascale]] on the coast of the [[Irish Sea]] in [[Cumbria]], [[England]]. The site is served by [[Sellafield railway station]]. |

||

== Ownership and facilities == |

== Ownership and facilities == |

||

Revision as of 09:43, 20 January 2010

Template:Infobox UK power station

Sellafield (formerly known as Windscale) is a nuclear processing and former electricity generating site, closed to the village of Seascale on the coast of the Irish Sea in Cumbria, England. The site is served by Sellafield railway station.

Ownership and facilities

Sellafield was previously owned and operated by British Nuclear Fuels plc (BNFL), but is now operated by Sellafield Ltd and, since 1 April 2005, has been owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority.

Facilities at the site include the THORP nuclear fuel reprocessing plant and the Magnox nuclear fuel reprocessing plant. It is also the site of the remains of Calder Hall, the world's first commercial nuclear power station, now being decommissioned, as well as some other older nuclear facilities.[1]

In 1981 the name of the site was changed back from Windscale to Sellafield, possibly in an attempt by the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority to disassociate the site from recent press reports about its safety.

History

The Sellafield site was originally occupied by ROF Sellafield, a Second World War Royal Ordnance Factory, which, with its sister factory, ROF Drigg, at Drigg, produced TNT.[nb 1] After the war, the Ministry of Supply adapted the site to produce materials for nuclear weapons, principally plutonium, and construction of the nuclear facilities commenced in 1947. The site was renamed Windscale to avoid confusion with the Springfields uranium processing factory near Preston. The two air-cooled, graphite-moderated Windscale reactors constituted the first British weapons grade plutonium-239 production facility, built for the British nuclear weapons programme of the late 1940s and the 1950s. Windscale was also the site of the prototype British Advanced gas-cooled reactor.

With the creation of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA) in 1954, ownership of Windscale Works passed to the Authority. The first of four Magnox reactors became operational in 1956 at Calder Hall, adjacent to Windscale, and the site became Windscale and Calder Works. Following the breakup of the UKAEA into a research division (UKAEA) and a production division, British Nuclear Fuels Ltd (BNFL) in 1971, the major part of the site was transferred to BNFL. In 1981 BNFL's Windscale and Calder Works was renamed Sellafield as part of a major reorganisation of the site. The remainder of the site remained in the hands of the UKAEA and is still called Windscale.[3]

Since its inception as a nuclear facility Sellafield has also been host to a number of reprocessing operations, which separate the uranium, plutonium and fission products from spent nuclear fuel.[4] The uranium can then be used in the manufacture of new nuclear fuel, or in applications where its density is an asset. The plutonium can be used in the manufacture of mixed oxide fuel (MOX) for thermal reactors, or as fuel for fast breeder reactors, such as the Prototype Fast Reactor at Dounreay. These processes, including the associated cooling ponds, require considerable amounts of water and the licence to extract up to 18,184.4 m³ a day (over 4 million gallons) and 6,637,306 m³ a year from Wast Water, formerly held by BNFL, is now held by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority.

Major plants

The Windscale Piles

Following the decision taken by the British government in January 1947 to develop nuclear weapons, Sellafield was chosen as the location of the plutonium production plant, with the initial fuel loading into the Windscale Piles commencing in July 1950.[5][6] By July 1952 the separation plant was being used to separate plutonium and uranium from spent fuel.

Unlike the early US nuclear reactors at Hanford, which consisted of a graphite core cooled by water, the Windscale Piles consisted of a graphite core cooled by air. Each pile contained almost 2000 tonnes (1,968 L/T) of graphite, and measured over 7.3 metres (24 ft) high by 15.2 metres (50 ft) in diameter. Fuel for the reactor consisted of rods of uranium metal, approximately 30 centimetres (12 in) long by 2.5 centimetres (1 in) in diameter, and clad in aluminium.[7]

The Windscale fire

The Windscale Piles were shut down following a fire in Pile 1 on 10 October 1957 which destroyed the core and released an estimated 750 terabecquerels (20,000 Ci) of radioactive material into the surrounding environment, including Iodine-131, which is taken up in the human body by the thyroid. Consequently milk and other produce from the surrounding farming areas had to be destroyed. Following the fire Pile 1 was unserviceable and Pile 2, although undamaged by the fire, was shut down as a precaution,[7] by which time UK had enough plutonium for some atomic bombs and work was progressing well at the FBR located close to Wick in north Scotland.

In the 1990s, the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority started to implement plans to decommission, disassemble and clean up both piles; the decommissioning is now partially complete. However, Pile 1 still contains about 15 tonnes (14.76 L/T) of highly unstable[citation needed] uranium fuel, and final completion of the decommissioning is not expected until at least 2037.[7]

The first generation reprocessing plant

The first generation reprocessing plant was built to extract the plutonium from spent fuel to provide fissile material for the UK's atomic weapons programme, and for exchange with the United States through the US-UK Mutual Defence Agreement. It operated from 1951 until 1964, with an annual capacity of 300 tonnes (295 L/T) of fuel, or 750 tonnes (738 L/T) of low burn-up fuel. Following the commissioning of the Magnox reprocessing plant, it was itself recycled to become a pre-handling plant to allow oxide fuel to be reprocessed in the Magnox plant, and was closed in 1973.

Calder Hall nuclear power station

Calder Hall was the world's first nuclear power station to deliver electricity in commercial quantities (although the 5 MW "semi-experimental" reactor at Obninsk in the Soviet Union was connected to the public supply in 1954).[1] The design was codenamed PIPPA (Pressurised Pile Producing Power and Plutonium) by the UKAEA to denote the plant's dual commercial and military role. Construction started in 1953.[8] Calder Hall had four Magnox reactors capable of generating 50 MWe of power each.[9] The reactors were supplied by the UKAEA and the turbines by C.A. Parsons & Company.[9] First connection to the grid was on 27 August 1956, and the plant was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 17 October 1956.[10] When the station closed on 31 March 2003, the first reactor had been in use for nearly 47 years.[11]

In its early life, it was primarily used to produce weapons-grade plutonium, with two fuel loads per year, and electricity production as a secondary purpose.[12] From 1964 it was mainly used on commercial fuel cycles, but it was not until April 1995 that the UK Government announced that all production of plutonium for weapons purposes had ceased.

The four Calder Hall cooling towers were demolished by controlled explosions on Saturday 29 September 2007.[13]

Windscale Advanced Gas Cooled Reactor (WAGR)

The Windscale Advanced Gas Cooled Reactor (WAGR)[14] was a prototype for the UK's second generation of reactors, the Advanced gas-cooled reactor or AGR, which followed on from the Magnox stations. The WAGR golfball is, along with the Pile chimneys, one of the iconic buildings on the Windscale site (Windscale being an independent site within the Sellafield complex). Construction was carried out by Mitchell Construction and completed in 1962.[15] This reactor was shut down in 1981, and is now part of a pilot project to demonstrate techniques for safely decommissioning a nuclear reactor.

Magnox reprocessing plant

In 1964 the Magnox reprocessing plant came on stream to reprocess spent nuclear fuel from the Magnox reactors.[16] The plant uses the "plutonium uranium extraction" Purex method for reprocessing spent fuel, with tributyl phosphate as an extraction agent. The Purex process produces uranium, plutonium and fission products as output streams. Over the 30 years from 1971 to 2001 B205 has reprocessed over 35,000 tonnes of Magnox fuel, with 15,000 tonnes of fuel being regenerated.[17] Magnox fuel is reprocessed since it corrodes if stored underwater, and routes for dry storage have not yet been proven.[18]

Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant

Between 1977 and 1978 an inquiry was held into an application by BNFL for outline planning permission to build a new plant to reprocess irradiated oxide nuclear fuel from both UK and foreign reactors. The inquiry was used to answer three questions:

"1. Should oxide fuel from United Kingdom reactors be reprocessed in this country at all; whether at Windscale or elsewhere?

2. If yes, should such reprocessing be carried on at Windscale?

3. If yes, should the reprocessing plant be about double the estimated site required to handle United Kingdom oxide fuels and be used as to the spare capacity, for reprocessing foreign fuels?"[19]

The result of the inquiry was that the new plant, the Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (Thorp) was given the go ahead in 1978, although it did not go into operation until 1994.

2005 Thorp plant leak

On April 19, 2005 83,000 litres of radioactive waste was discovered to have leaked in the Thorp reprocessing plant from a cracked pipe into a huge stainless steel-lined concrete sump chamber built to contain leaks.

A discrepancy between the amount of material entering and exiting the Thorp processing system had first been noted in August 2004. Documentation of this finding was not passed up to the appropriate administrator.

Other indicators of a problem included a rise in temperature in the sump chamber and findings of radioactive fluid there, but these were ignored. The spill was recognized only after another audit suggested that further material was missing, prompting plant operators, after several days' delay, to train an automated camera on the faulty pipe and to actually measure the volume of liquid in the sump.

Responsible administrators have been disciplined. Some 19 tonnes of uranium and 160 kilograms of plutonium dissolved in nitric acid has been pumped from the sump vessel into a holding tank away from the Thorp plant.

Highly Active Liquor Evaporation and Storage

Highly Active Liquor Evaporation and Storage (HALES) is a department at Sellafield. It conditions nuclear waste streams from the Magnox and Thorp reprocessing plants, prior to transfer to the Windscale Vitrification Plant.

The Vitrification Plant

In 1991 the Windscale Vitrification Plant (WVP), which seals high-level radioactive waste in glass, was opened. In this plant, liquid wastes are mixed with glass and melted in a furnace, which when cooled forms a solid block of glass.

The plant has three process lines and is based on the French AVM procedure. Principal item is an inductively heated melting furnace, in which the calcined waste is merged with glass frit (glass beads of 1 to 2 mm in diameter). The melt is placed into waste containers, which are welded shut, their outsides decontaminated and then brought into air-cooled storage facilities. This storage consists of 800 vertical storage tubes, each capable of storing ten containers. The total storage capacity is 8000 containers, and 2280 containers have been stored to 2001. Vitrification shall ensure safe storage of waste in the UK for the middle to long term.

The Sellafield MOX Plant

Construction of the Sellafield MOX Plant (SMP) was completed in 1997, though justification for the operation of the plant was not achieved until October 2001.[20] Mixed oxide, or MOX fuel, is a blend of plutonium and natural uranium or depleted uranium which behaves similarly (though not identically) to the enriched uranium feed for which most nuclear reactors were designed. MOX fuel is an alternative to Low enriched uranium (LEU) fuel used in the light water reactors which predominate in nuclear power generation. MOX also provides a means of using excess weapons-grade plutonium (from military sources) to produce electricity.

Designed with a plant capacity of 120 tonnes/year, it achieved a total output of only 5 tonnes during its first five years of operation.[20] In 2008 orders for the plant had to be fulfilled at COGEMA in France,[21] and the plant was reported in the media as "failed"[22][23] with a total build and operation cost of £1.2 billion.[24]

Enhanced Actinide Removal Plant

In its early days, Sellafield discharged low-level radioactive waste into the sea, using a flocculation process to remove radioactivity from liquid effluent before discharge. Metals dissolved in acidic effluents produced a metal hydroxide flocculant precipitate following the addition of ammonium hydroxide. The suspension was then transferred to settling tanks where the precipitate would settle out, and the remaining clarified liquor, or supernate, would be discharged to the sea. In 1994 the Enhanced Actinide Removal Plant (EARP) was opened. In EARP the effectiveness of the process is enhanced by the addition of reagents to remove the remaining soluble radioactive species. EARP has recently (2004) been enhanced to further reduce the quantities of Technetium-99 released to the environment.[25]

Fellside Power Station

Fellside Power Station is a 168MWe CHP gas-fired power station near the Sellafield site, which it supplies with steam and heat. It is run as Fellside Heat and Power Ltd, is wholly owned by Sellafield Ltd and is managed by PX Ltd and Doosan Babcock. It was built in 1993, being originally equally owned by BNFL and Scottish Hydro Electric (which became Scottish and Southern Energy in December 1998). The station uses three General Electric Frame 6001B gas turbines, with power entering the National Grid via a 132kV transformer. BNFL bought SSE's 50% share in January 2002.[26]

Sellafield and the local community

Sellafield directly employs around 10,000 people[27] and is one of the two largest, non-governmental, employers in West Cumbria (along with BAE Systems at Barrow-in-Furness),[28] with approximately 90% of the employees coming from West Cumbria.[29] Because of the increase in local unemployment following any run down of Sellafield operations, the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (and HMG) is concerned that this needs to be managed.[30]

Sellafield Centre - Business and Information Centre

Formerly the Sellafield Visitors' Centre, it is now the Business and Information Centre and is open Mon - Fri only. The centre is used for business events such as supplier forums and 'Meet the Buyer' events. It is still open to the public but only at selected times.

At its peak, the Visitors' Centre attracted an average of 1,000 people per day. In recent years, its popularity has deteriorated, prompting the change from tourist attraction to conference facility.

Controversy

The site has been the subject of much controversy because of discharges of radioactive material, mainly accidental but some alleged to have been deliberate. Since the early 1970s and the rise of the environmental movement in the US and Europe, there has also been general scepticism of the nuclear industry. In part this has not been helped by the industry's early connections to the nuclear weapons programme.

Between 1950 and 2000 there have been 21 serious incidents or accidents involving some off-site radiological releases that merited a rating on the International Nuclear Event Scale, one at level 5, five at level 4 and fifteen at level 3. Additionally during the 1950s and 1960s there were protracted periods of known, deliberate, discharges to the atmosphere of plutonium and irradiated uranium oxide particulates.[31] These frequent incidents, together with the large 2005 Thorp plant leak which was not detected for nine months, have led some to doubt the effectiveness of the managerial processes and safety culture on the site over the years.

In the hasty effort to build the 'British Bomb' in the 1940s and 1950s, radioactive waste was diluted and discharged by pipeline into the Irish Sea. Some[32] claim that the Irish Sea remains one of the most heavily contaminated seas in the world because of these discharges. The OSPAR Commission reports an estimated 200 kg of plutonium has been deposited in the marine sediments of the Irish Sea.[33] Cattle and fish in the area are contaminated with plutonium-239 and caesium-137 from these sediments and from other sources such as the radioactive rain that fell on the area after the Chernobyl disaster and the results of atmospheric atomic weapons tests prior to the partial test ban treaty in 1963. Most of the area's long-lived radioactive technetium comes from the reprocessing of spent nuclear fuel at the Sellafield facility.[34] Template:Inote Technetium-99 is a radioactive element which is produced by nuclear fuel reprocessing, and also as a by-product of medical facilities (for example Ireland is responsible for the discharge of approximately 6.78 GBq of Technetium-99 each year despite not having a nuclear industry).[35] Because it is almost uniquely produced by nuclear fuel reprocessing, Technetium-99 is an important element as part of the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR) since it provides a good tracer for discharges into the sea.

In itself, the technetium discharges do not represent a significant radiological hazard,[36] and recent studies have noted "...that in the most recently reported dose estimates for the most exposed Sellafield group of seafood consumers (FSA/SEPA 2000), the contributions from Technetium-99 and actinide nuclides from Sellafield (<100 µSv) was less than that from 210Po attributable to discharges from the Whitehaven phosphate processing plant and probably less than the dose from naturally occurring background levels of 210Po."[37] Because of the need to comply with OSPAR, British Nuclear Group (the licensing company for Sellafield) have recently commissioned a new process in which Technetium-99 is removed from the waste stream and vitrified in glass blocks.[38]

There has been concern that the Sellafield area will become a major dumping ground for unwanted nuclear material, since there are currently no long-term facilities for storing High-Level Waste (HLW), although the UK has current contracts to reprocess spent fuel from all over the world. However, contracts signed since 1976 between BNFL and overseas customers require that all HLW be returned to the country of origin. The UK retains low- and intermediate-level waste resulting from its reprocessing activity, and instead ships out a radiologically equivalent amount of its own HLW. This substitution policy is intended to be environmentally neutral and to speed "return" of overseas material by reducing the number of shipments required, since HLW is far less bulky.[39]

Organ removal inquiry

In 2007 an inquiry was launched into the removal of tissue from a total of 65 deceased nuclear workers, some of whom worked at Sellafield.[40] It has been alleged that the tissue was removed without seeking permission from the relatives of the late workers. Michael Redfern QC has been appointed to lead the investigation.[41]

MOX fuel quality data falsification

The MOX Demonstration Facility was a small-scale plant to produce commercial quality MOX fuel for light water reactors. The plant was commissioned between 1992 and 1994, and until 1999 produced fuel for use in Switzerland, Germany and Japan.

In 1999 it was discovered that the plant's staff had been falsifying some quality assurance data since 1996.[42] A Nuclear Installations Inspectorate (NII) investigation concluded four of the five work-shifts were involved in the falsification, though only one worker admitted to falsifying data, and that "the level of control and supervision ... had been virtually non existent.". The NII stated that the safety performance of the fuel was not affected as there was also a primary automated check on the fuel. Nevertheless "in a plant with the proper safety culture, the events described in this report could not have happened." and there were systematic failures in management.[43]

BNFL had to pay compensation to the Japanese customer, Kansai Electric, and take back a flawed shipment of MOX fuel from Japan.[44] BNFL's Chief Executive John Taylor resigned,[45] after initially resisting resignation when the NII's damning report was published.[46]

The "Beach Incident"

1983 was the year of the "Beach Discharge Incident" in which high radioactive discharges containing ruthenium and rhodium 106, both beta-emitting isotopes, resulted in the closure of a beach.[47] BNFL received a fine of £10,000 for this discharge.[48] 1983 was also the year in which Yorkshire Television produced a documentary "Windscale: The Nuclear Laundry", which claimed that the low levels of radioactivity that are associated with waste streams from nuclear plants such as Sellafield did pose a non-negligible risk.[49]

Cancer risks

According to Stephanie Cooke, the British Government has been "at pains over the years to play down attempts to correlate cancers with Sellafield radioactivity, particularly when it involves individuals living near the plant but not working at it".[50]

In 1983, the Medical Officer of West Cumbria announced that cancer fatality rates were actually lower around the nuclear plant than elsewhere in Great Britain.[51] In the early 1990s, concern was raised in the UK about apparent clusters of leukaemia near nuclear facilities.

A 1997 Ministry Ministry of Health report stated that children living close to Sellafield had twice as much plutonium in their teeth as children living more than 100 miles away. Health Minister Melanie Johnson said the quantities were minute and "presented no risk to public health". Dundee University's Professor Eric Wright, a leading expert on blood disorders, challenged this claim, saying that even microscopic amounts of the man-made element might cause cancer.[50]

Detailed studies carried out by the Committee on Medical Aspects of Radiation in the Environment (COMARE) in 2003 found no evidence of raised childhood cancer around nuclear power plants, but did find an excess of leukaemia and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) near other nuclear installations including Sellafield, AWE Burghfield and UKAEA Dounreay. COMARE's opinion is that "the excesses around Sellafield and Dounreay are unlikely to be due to chance, although there is not at present a convincing explanation for them".[52] In earlier reports COMARE had suggested that "..no single factor could account for the excess of leukaemia and NHL but that a mechanism involving infection may be a significant factor affecting the risk of leukaemia and NHL in young people in Seascale."[53]

Irish objections

Sellafield has been a matter of some consternation in Ireland, with the Irish Government and some members of the population concerned at the risk that such a facility may pose to the country. The Irish government has made formal complaints about the facility, and recently came to a friendly agreement with the British Government about the issue, as part of which the Radiological Protection Institute of Ireland and An Garda Síochána (Irish Police Force) are now allowed access to the site. However, Irish government policy remains that of seeking the closure of the facility.

Norwegian objections

Similar objections to those held by the Irish government have been voiced by the Norwegian government since 1997. Monitoring undertaken by the Norwegian Radiation Protection Board has shown that the prevailing sea currents transport radioactive materials leaked into the sea at Sellafield along the entire coast of Norway and water samples have shown up to ten-fold increases in such materials as Technetium-99.[54] Fears for the reputation of Norwegian fish as a safe food product have been a concern of the country's fishing industry, though the radiation levels have not been conclusively proved as dangerous for the fish.[citation needed] The Norwegian government is also seeking closure of the facility.[55]

Finances

In 2003 it was announced that the Thorp reprocessing plant would be closed in 2010. Originally predicted to make profits for BNFL of £500m, by 2003 it had made losses of over £1bn.[56] Subsequently Thorp was closed for almost two years from 2005, after a leak had been undetected for 9 months. Production eventually restarted at the plant in early 2008; but almost immediately had to be put on hold again, for an underwater lift that takes the fuel for reprocessing to be repaired.[57]

In November 2008 Sellafield was taken over by a new US-led consortium (US company URS Washington, French firm Areva and the UK company Amec) for decommissioning, as part of a 5-year £6.5bn contract. In October 2008 it was revealed that the British government had agreed to issue Sellafield an unlimited indemnity against future accidents; according to The Guardian, "the indemnity even covers accidents and leaks that are the consortium's fault." The indemnity had been rushed through prior to the summer parliamentary recess without notifying parliament.[58]

In 2009 Sellafield decommissioning accounts for 40% of the budget of the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority - over £1.1bn.[59]

Plutonium records discrepancy

On February 17, 2005, the UK Atomic Energy Authority reported that 29.6 kg (65.3 lb) of plutonium was unaccounted for in auditing records at the Sellafield nuclear fuel reprocessing plant. The operating company, the British Nuclear Group, described this as a discrepancy in paper records and not as indicating any physical loss of material. They pointed out that the error amounted to about 0.5%, whereas International Atomic Energy Agency regulations permit a discrepancy up to 1% as the amount of plutonium recovered from the reprocessing process never precisely matches the pre-process estimates. The inventories in question were accepted as satisfactory by Euratom, the relevant regulatory agency.[60]

Decommissioning

Sellafield's biggest decommissioning challenges relate to the leftovers of the early nuclear research and nuclear weapons programmes.[61] Sellafield houses "the most hazardous industrial building in western Europe" (building B30) and the second-most (building B38), which hold a variety of leftovers from the first Magnox plants in ageing ponds.[61] Some of the problems with B38 date back to the 1972 miners' strike: the reactors were pushed so hard that waste processing couldn't keep up, and "cladding and fuel were simply thrown into B38's cooling ponds and left to disintegrate."[61] Some of the problems date back to the original nuclear weapons programme at Sellafield, when Piles 1 and 2 were constructed at breakneck speed, and safe disposal was not a priority. Building B41 still houses the aluminium cladding for the uranium fuel rods of Piles 1 and 2, and is modelled on a grain silo, with waste tipped in at the top and argon gas added to prevent fires.[61]

In 2009 Sellafield decommissioning accounts for 40% of the budget of the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority - over £1.1bn.[62] Sellafield decommissioning and waste disposal is expected to cost the taxpayer £1.5bn per year for many years.[61]

Sellafield in popular culture

Music

In 1992, rock bands U2, Public Enemy, Big Audio Dynamite II, and Kraftwerk held a "Stop Sellafield" concert for Greenpeace to protest the nuclear factory. Stop Sellafield: The Concert was later released that year on VHS in the UK, and all proceeds went directly to Greenpeace.

U2's performance from the "Stop Sellafield" concert was held during their Zoo TV Tour on 19 June 1992 at the G-Mex Centre in Manchester, England. Two tracks from the concert, "The Fly" and "Even Better Than the Real Thing," were later released on the band's "City of Blinding Lights" CD single and on the Zoo TV: Live from Sydney DVD.

Since 1992, German band Kraftwerk has introduced their song "Radioactivity" in their live shows with a video clip criticizing the Sellafield-2 reactor for radiation released into the atmosphere during typical operation and the dangers of reprocessing plutonium in regard to nuclear proliferation:

Sellafield-2 will produce 7.5 tons of plutonium every year. 1.5 kilogram of plutonium make a nuclear bomb.

Sellafield-2 will release the same amount of radioactivity into the environment as Chernobyl every 4.5 years. One of these radioactive substances, Krypton-85, will cause death and skin cancer.

This introduction can be heard on their 2005 live album and DVD Minimum-Maximum. Sellafield-2 was the name given by environmental groups including Greenpeace to a proposed second plant to reprocess oxide fuel (it is not obvious how seriously proposed, a public enquiry was never opened).

Other

Fallout, a programme shown in 2006 on the Irish national TV station RTÉ, was a documentary-style drama showing the possible effects of a serious accident at Sellafield. The programme highlighted the fact that an accident could cause long scale contamination of Ireland's most densely populated areas, including its capital city, Dublin.

Sellafield was also featured in the Arthur Scargill episode of the Comic Strip, and is referred to in the film The Medusa Touch (as Windscale). Not the Nine O'Clock News also had a sketch, with a nod to a popular Ready Brek advert, about glowing children and Sellafield. One of the numerous Comic Relief live albums features a song called I Believe, where the singer takes a 'yeah right' attitude to various social matters of the day. One line runs: "I'm prepared to believe that Sellafield's not leaking, and I believe that Ian Paisley thinks before speaking."

Comedian Lenny Henry, impersonating newscaster Trevor McDonald, once reported that "Windscale is to be renamed Sellafield, because it sounds nicer. In future, radiation will be referred to as magic moonbeams".

Sellafield was the subject of Marilynne Robinson's 1989 book, Mother Country, a critique of British nuclear policy.

Notes

- ^ Drigg is now the site of the Low Level Waste Repository for nuclear waste. 70% of the waste received at Drigg originates from Sellafield.[2]

See also

- Nuclear Power

- Nuclear reprocessing

- Nuclear fuel cycle

- Windscale fire

- COGEMA La Hague site (a similar site in France)

- List of cancer clusters

- List of nuclear accidents

- List of nuclear reactors

- Nuclear power in the United Kingdom

- Energy policy of the United Kingdom

- Energy use and conservation in the United Kingdom

- Sellafield railway station

- Cumbrians Opposed to a Radioactive Environment

- Windscale: Britain’s Biggest Nuclear Disaster

- Tom Tuohy

- Hanford Site

References

- ^ a b Kragh, Helge (1999). Quantum Generations: A History of Physics in the Twentieth Century. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 286. ISBN 0691095523.

- ^ unattributed (25 January 1989). "BNF shows its rubbish dump". The Journal. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Newcastle Chronicle and Journal Ltd: 18.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Cassidy, Nick, and Patrick Green. 1993. Sellafield: The contaminated legacy. London: Friends of the Earth.

- ^ Openshaw, Stan, Steve Carver, and John Fernie. 1989. Britain’s nuclear waste: Siting and safety. London: Bellhaven Press.

- ^ Sutyagin, Igor (1996). "The Role Of Nuclear Weapons And Its Possible Future Missions". NATO. pp. I.3. The Great Britain. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ^ unattributed (undated). "Sellafield Ltd Timeline". Sellafield Ltd. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ a b c unattributed (14 May 2004). "Getting to the core issue". The Engineer. Retrieved 2008-10-23.

- ^ The Nuclear Businesses

- ^ a b Nuclear Power Plants in the UK

- ^ "History of Sellafield". Sellafield Web Page. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "First nuclear power plant to close". Guardian Unlimited. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ Peter Hayes. "Should the United States supply light water reactors to Pyongyang?". Nautilus Pacific Research. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Sellafield towers are demolished". BBC News. 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ "Project WAGR". Project WAGR.

- ^ Indictment: Power & Politics in the Construction Industry, David Morrell, Faber & Faber, 1987, ISBN 978-0571149858

- ^ "History of Sellafield". Sellafield Web Page. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Continued discharges from Sellafield for ten more years". Bellona. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "RWMAC's Advice to Ministers on the Radioactive Waste Implications of Reprocessing". RWMAC. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Windscale Inquiry". BOPCRIS - Unlocking Key British Government Publications. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ a b Malcolm Wicks (22 February 2008), Hansard, Written Answers: Sellafield ([dead link] – Scholar search), "Hansard, 22 Feb 2008 : Column 1034W, retrieved 2008-03-12

{{citation}}: External link in|format= - ^ Geoffrey Lean (9 March 2008). "'Dirty bomb' threat as UK ships plutonium to France". "The Independent. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ Geoffrey Lean (9 March 2008). "Minister admits total failure of Sellafield 'MOX' plant". The Independent. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ "MOX Fuel Output for Shikoku Electric Power to Begin in March". The Japan Corporate News Network. February 29, 2008. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ Jon Swaine (7 April 2009). "Nuclear recycling plant costs £1.2 billion and still doesn't work". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- ^ Ben Irons. "Treating a 50-year-old legacy of radioactive sludge waste". Engineer Live. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ British Nuclear Fuels plc’s completed acquisition of Fellside Heat and Power Limited (PDF), OFGEM, March 2002, retrieved 2008-12-08

- ^ "Site Statistics". NuclearSites Web Site. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "THE ECONOMY OF CUMBRIA: THE SIGNIFICANCE OF MAJOR EMPLOYERS" (PDF). Centre for Regional Economic Development. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Nuclear decommissioning at Sellafield". BBC News. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Government pledges to safeguard West Cumbria's future". Government News Network. 1 November 2004. GNN ref 104585P.

- ^ G A M Webb; et al. (2006). "Classification of events with an off-site radiological impact at the Sellafield site between 1950 and 2000, using the International Nuclear Event Scale". Journal of Radiological Protection. 26: 33. doi:10.1088/0952-4746/26/1/002.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.greenpeace.org.uk/nuclear/sellafield-nuclear-reprocessing-facility

- ^ "Quality Status Report 2000 for the North East-Atlantic (Regional QSR III, Chapter 4 Chemistry, p66" (PDF). OSPAR Commission. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- ^ "Technetium-99 Behavior in the Terrestrial Environment - Field Observations and Radiotracer Experiments-" (PDF). Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemical Sciences, Vol. 4, No.1, pp. A1-A8, 2003. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ "Report of Ireland on the Implementation of the OSPAR Strategy with regard to Radioactive Substances (June 2001)" (PDF). Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government. pp. 2 para.9. Retrieved 2008-04-04.

- ^ "News Release: MINISTERS ANNOUNCE DECISION ON TECHNETIUM-99". Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ J D Harrison; et al. "Gut transfer and doses from environmental technetium". J. Radiol. Prot. 21 9-11. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

{{cite web}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ "44 years of discharges prevented after early end to Sellafield waste programme". Latest News: British Nuclear Group, 26th January 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ "INTERMEDIATE LEVEL RADIOACTIVE WASTE SUBSTITUTION" (PDF). DTI. Retrieved 2006-08-23.

- ^ "Sellafield organ removal inquiry". BBC News. 2007-04-18. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- ^ Walker, Peter (2007-07-10). "Sellafield body parts scandal". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-09-25.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (15.09.99). "Japan launches inquiry into BNFL". Guardian Newspapers. p. 9.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nuclear Installations Inspectorate (18 February 2000). "An Investigation into the Falsification of Pellet Diameter Data in the MOX Demonstration Facility at the BNFL Sellafield Site and the Effect of this on the Safety of MOX Fuel in Use". Retrieved 2006-11-18.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "BNFL ends Japan nuclear row". BBC. 11 July 2000. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ^ "Safety overhaul at Sellafield". BBC. 17 April 2000. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ^ "BNFL chief determined to stay despite damning safety report". Daily Telegraph. 19 February 2000. Retrieved 2006-11-18.

- ^ Morris, Michael (18 February 1984). "Warnings go up on nuclear site beaches". The Guardian. UK: Guardian Newspapers: 3.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Written answers for Friday 5th May 2000". Hansard. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ "Science: Leukaemia and nuclear power stations". New Scientist. Retrieved 2006-08-21.

- ^ a b Stephanie Cooke (2009). In Mortal Hands: A Cautionary History of the Nuclear Age, Black Inc., p. 356.

- ^ Foot, Paul, London Review of Books, "Nuclear Nightmares", August 1988

- ^ "COMARE 10th Report: The incidence of childhood cancer around nuclear installations in Great Britain". Committee on Medical Aspects of Radiation in the Environment. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

- ^ "Summary of the work of COMARE as published in its first six reports" (PDF). Committee on Medical Aspects of Radiation in the Environment. Retrieved 2006-08-25.

- ^ Brown, Paul (20 December 1997). "Norway fury at UK nuclear waste flood". The Guardian. UK: Guardian Newspapers: 11.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Norway concerned over reopening of THORP facility at Sellafield". www.norway.org.uk. Retrieved 2009-01-08.

- ^ Sellafield reprocessing plant to close by 2010 The Times, 26 August 2003

- ^ Geoffrey Lean, 'Shambolic' Sellafield in crisis again after damning safety report, The Independent, 3 February 2008.

- ^ The Guardian, 27 October 2008, MP's anger as state bears cost of any Sellafield disaster

- ^ More government funding for the NDA Nuclear Engineering International, 3 August 2009

- ^ "Missing plutonium 'just on paper'". BBC News. 2005-02-17. Retrieved 2006-08-22.

- ^ a b c d e The Observer, 19 April 2009, Sellafield: the most hazardous place in Europe

- ^ More government funding for the NDA Nuclear Engineering International, 3 April 2009

Further reading

- Sellafield, Erik Martiniussen, Bellona Foundation, December 2003, ISBN 82-92318-08-9

- Technetium-99 Behaviour in the Terrestrial Environment - Field Observations and Radiotracer Experiments, Keiko Tagami, Journal of Nuclear and Radiochemical Sciences, Vol. 4, No.1, pp. A1-A8, 2003

- The excess of childhood leukaemia near Sellafield: a commentary on the fourth COMARE report, L J Kinlen et al. 1997 J. Radiol. Prot. 17 63-71

External links

- Nuclear Decommissioning Authority

- Sellafield Ltd

- British Nuclear Group

- British Nuclear Fuels Limited

- National Nuclear Laboratory

- go-experimental.com (Another Sellafield Visitors Centre interactive site)

- An article on the Windscale fire, by the Lake District Tourist Board

- Nuclear Tourist

- BBC retrospective on the accident report

- Sellafield awaits nuclear power's rebirth, by Jorn Madslien, BBC News

- http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/4818370.stm, by Jorn Madslien, BBC News

- The sale of Britain's nuclear giant, by Jorn Madslien, BBC News

- All about Sellafield

- Project WAGR to safely decommission the AGR at Sellafield

- Board of Inquiry Report

- Wiki devoted to education about nuclear power

- "Blast from the past" Guardian article

- Calder Hall Cooling towers demolition page

- Annotated references on Sellafield from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues

- Articles with dead external links from June 2008

- Buildings and structures in Cumbria

- Energy in the United Kingdom

- Natural gas-fired power stations in England

- Military nuclear reactors

- Nuclear accidents

- Nuclear power stations in England

- Nuclear weapons programme of the United Kingdom

- Nuclear reprocessing

- Power stations in North West England

- Radioactive waste

- Former power stations