Selenol

Selenols are organic compounds that contain the functional group with the connectivity C−Se−H. Selenols are sometimes also called selenomercaptans and selenothiols. Selenols are one of the principal classes of organoselenium compounds.[1] A well-known selenol is the amino acid selenocysteine.

Structure, bonding, properties

[edit]Selenols are structurally similar to thiols, but the C−Se bond is about 8% longer at 196 pm. The C−Se−H angle approaches 90°. The bonding involves almost pure p-orbitals on Se, hence the near 90 angles. The Se−H bond energy is weaker than the S−H bond, consequently selenols are easily oxidized and serve as H-atom donors. The Se-H bond is weaker than the S−H bond as reflected in their respective bond dissociation energy (BDE). For C6H5Se−H, the BDE is 326 kJ/mol, while for C6H5S−H, the BDE is 368 kJ/mol.[2]

Selenols are about 1000 times stronger acids than thiols: the pKa of CH3SeH is 5.2 vs 8.3 for CH3SH. Deprotonation affords the selenolate anion, RSe−, most examples of which are highly nucleophilic and rapidly oxidized by air.[3]

The boiling points of selenols tend to be slightly greater than for thiols. This difference can be attributed to the increased importance of stronger van der Waals bonding for larger atoms. Volatile selenols have highly offensive odors.

Applications and occurrence

[edit]Selenols have few commercial applications, being limited by the toxicity of selenium as well as the sensitivity of the Se−H bond. Their conjugate bases, the selenolates, also have limited applications in organic synthesis.

Biochemical role

[edit]Selenols are important in certain biological processes. Three enzymes found in mammals contain selenols at their active sites: glutathione peroxidase, iodothyronine deiodinase, and thioredoxin reductase. The selenols in these proteins are part of the essential amino acid selenocysteine.[3] The selenols function as reducing agents to give selenenic acid derivative (RSe−OH), which in turn are re-reduced by thiol-containing enzymes. Methaneselenol (commonly named "methylselenol") (CH3SeH), which can be produced in vitro by incubating selenomethionine with a bacterial methionine gamma-lyase (METase) enzyme, by biological methylation of selenide ion or in vivo by reduction of methaneseleninic acid (CH3−Se(=O)−OH), has been invoked to explain the anticancer activity of certain organoselenium compounds.[4][5][6] Precursors of methaneselenol are under active investigation in cancer prevention and therapy. In these studies, methaneselenol is found to be more biologically active than ethaneselenol (CH3CH2SeH) or 2-propaneselenol ((CH3)2CH(SeH)).[7]

Preparation

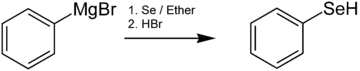

[edit]Selenols are usually prepared by the reaction of organolithium reagents or Grignard reagents with elemental Se. For example, benzeneselenol is generated by the reaction of phenylmagnesium bromide with selenium followed by acidification:[8]

Another preparative route to selenols involves the alkylation of selenourea, followed by hydrolysis. Selenols are often generated by reduction of diselenides followed by protonation of the resulting selenolate:

- 2 RSe−SeR + 2 Li+[HB(CH2CH3)3]− → 2 RSe−Li+ + 2 B(CH2CH3)3 + H2

- RSe−Li+ + HCl → RSeH + LiCl

Dimethyl diselenide can be easily reduced to methaneselenol within cells.[9]

Reactions

[edit]Selenols are easily oxidized to diselenides, compounds containing an Se−Se bond. For example, treatment of benzeneselenol with bromine gives diphenyl diselenide.

- 2 C6H5SeH + Br2 → (C6H5Se)2 + 2 HBr

In the presence of base, selenols are readily alkylated to give selenides. This relationship is illustrated by the methylation of methaneselenol to give dimethylselenide.

Safety

[edit]Organoselenium compounds (or any selenium compound) are cumulative poisons despite the fact that trace amounts of Se are required for health.[10]

See also

[edit]Selenol, alcohol, thiol acidity order

References

[edit]- ^ Tanini, Damiano; Capperucci, Antonella (2021). "Synthesis and Applications of Organic Selenols". Advanced Synthesis & Catalysis. 363 (24): 5360–5385. doi:10.1002/adsc.202101147. hdl:2158/1259438. S2CID 244109470.

- ^ Lide, David R., ed. (2006). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (87th ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0487-3.

- ^ a b Wessjohann L, Schneider A, Abbas M, Brandt W (2007). "Selenium in Chemistry and Biochemistry in Comparison to Sulfur". Biological Chemistry. 388 (10): 997–1006. doi:10.1515/BC.2007.138. PMID 17937613. S2CID 34918691.

- ^ Zeng H, Briske-Anderson M, Wu M, Moyer MP (2012). "Methylselenol, a Selenium Metabolite, Plays Common and Different Roles in Cancerous Colon HCT116 Cell and Noncancerous NCM460 Colon Cell Proliferation". Nutrition and Cancer. 64 (1): 128–135. doi:10.1080/01635581.2012.630555. PMID 22171558. S2CID 21968566.

- ^ Fernandes AP, Wallenberg M, Gandin V, Misra S, Marzano C, Rigobello MP, et al. (2012). "Methylselenol Formed by Spontaneous Methylation of Selenide Is a Superior Selenium Substrate to the Thioredoxin and Glutaredoxin Systems". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e50727. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...750727F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050727. PMC 3511371. PMID 23226364.

- ^ Ip C, Dong Y, Ganther HE (2002). "New Concepts in Selenium Chemoprevention". Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 21 (3–4): 281–289. doi:10.1023/a:1021263027659. PMID 12549766. S2CID 7636317.

- ^ Zuazo A, Plano D, Ansó E, Lizarraga E, Font M, Irujo JJ (2012). "Cytotoxic and Proapototic Activities of Imidoselenocarbamate Derivatives Are Dependent on the Release of Methylselenol". Chemical Research in Toxicology. 25 (11): 2479–2489. doi:10.1021/tx300306t. PMID 23043559.

- ^ Foster DG (1944). "Selenophenol". Organic Syntheses. 24: 89. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.024.0089.

- ^ Gabel-Jensen C, Lunøe K, Gammelgaard B (2010). "Formation of methylselenol, dimethylselenide and dimethyldiselenide in in vitro metabolism models determined by headspace GC-MS". Metallomics. 2 (2): 167–173. doi:10.1039/b914255j. PMID 21069149.

- ^ Rayman, M (2012). "Selenium and human health" (PDF). The Lancet. 379 (9822): 1256–1268. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61452-9. PMID 22381456. S2CID 34151222.