Religion in Scotland

| Religion in Scotland |

|---|

|

|

|

As of the 2022 census, None was the largest category of belief in Scotland, chosen by 51.1% of the Scottish population identifying when asked: "What religion, religious denomination or body do you belong to?"[1] This represented an increase from the 2011 figure of 36.7%. 38.8% identified as Christian with most of them declaring affiliation with the Church of Scotland (52.5% of Christians; 20.4% of the total population) and the Catholic Church (34.3% of Christians; 13.3% of the total population). The only other religious persuasions with more than 1% affiliation were 'Other Christian' and Muslim at 5.1% and 2.2% of the total population, respectively.

The Church of Scotland, a Presbyterian denomination often known as The Kirk, is recognised in law as the national church of Scotland. It is not an established church and is independent of state control. The Catholic Church is especially important in West Central Scotland and parts of the Highlands. Scotland's third largest church is the Scottish Episcopal Church.[2] There are also multiple smaller Presbyterian churches, all of which either broke away from the Church of Scotland or themselves separated from churches which previously did so. The 2019 Scottish Household survey had a rate of the proportion of adults reporting not belonging to a religion of 56%. The trend of declining religious belief coincided with a sharp decrease since 2009 in the proportion of people who report that they belong to the Church of Scotland, from 34% to 20% of adults.

Other religions have established a presence in Scotland, mainly through immigration and higher birth rates among ethnic minorities. Those with the most adherents in the 2022 census are Islam (2.2%, up from 1.4% in 2011), Hinduism (0.6%), Buddhism (0.3%) and Sikhism (0.2%). Minority faiths include Modern Paganism and the Baháʼí Faith. There are also various organisations which actively promote humanism and secularism. Since 2016, humanists have conducted more weddings in Scotland each year than either the Catholic Church, Church of Scotland, or any other religion and by 2022 the number of humanist marriages outnumbered all religious ceremonies combined.[3][4]

Census statistics

[edit]The statistics from the 2022, 2011 and 2001 censuses are set out below.

Religion in Scotland (2022)[5]

| Current religion | 2001[6] | 2011[7][8] | 2022[9] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | % | Number | % | Number | % | |

| Christianity | 3,294,545 | 65.1 | 2,850,199 | 53.8 | 2,110,405 | 38.8 |

| –Church of Scotland | 2,146,251 | 42.4 | 1,717,871 | 32.4 | 1,107,796 | 20.4 |

| –Catholic | 803,732 | 15.9 | 841,053 | 15.9 | 723,322 | 13.3 |

| –Other Christian | 344,562 | 6.8 | 291,275 | 5.5 | 279,287 | 5.1 |

| Islam | 42,557 | 0.8 | 76,737 | 1.4 | 119,872 | 2.2 |

| Hinduism | 5,564 | 0.1 | 16,379 | 0.3 | 29,929 | 0.6 |

| Buddhism | 6,830 | 0.1 | 12,795 | 0.2 | 15,501 | 0.3 |

| Sikhism | 6,572 | 0.1 | 9,055 | 0.2 | 10,988 | 0.2 |

| Judaism | 6,448 | 0.1 | 5,887 | 0.1 | 5,847 | 0.1 |

| Paganism | – | – | – | – | 19,113 | 0.4 |

| Other religion | 26,974 | 0.5 | 15,196 | 0.3 | 12,425 | 0.2 |

| No religion | 1,394,460 | 27.6 | 1,941,116 | 36.7 | 2,780,900 | 51.1 |

| Religion not stated | 278,061 | 5.5 | 368,039 | 7.0 | 334,862 | 6.2 |

| Total population | 5,062,011 | 100.0 | 5,295,403 | 100.0 | 5,439,842 | 100.0 |

History

[edit]

Christianity was probably introduced to what is now southern Scotland during the Roman occupation of Britain.[10][11] It was mainly spread by missionaries from Ireland from the 5th century and is associated with St Ninian, St Kentigern, and St Columba.[12] The Christianity that developed in Ireland and Scotland differed from that led by Rome, particularly over the method of calculating Easter and the form of tonsure, until the Celtic church accepted Roman practices in the mid-7th century.[13] Christianity in Scotland was strongly influenced by monasticism, with abbots being more significant than bishops.[14] In the Norman period, there were a series of reforms resulting in a clearer parochial structure based around local churches; and large numbers of new monastic foundations, which followed continental forms of reformed monasticism, began to predominate.[14] The Scottish church also established its independence from England, developing a clear diocesan structure and becoming a "special daughter of the see of Rome" but continued to lack Scottish leadership in the form of archbishops.[15] In the late Middle Ages the Crown was able to gain greater influence over senior appointments, and two archbishoprics had been established by the end of the 15th century.[16] There was a decline in traditional monastic life but the mendicant orders of friars grew, particularly in the expanding burghs.[16][17] New saints and cults of devotion also proliferated.[15][18] Despite problems over the number and quality of clergy after the Black Death in the 14th century, and evidence of heresy in the 15th century, the Church in Scotland remained stable.[19]

During the 16th century, Scotland underwent a Protestant Reformation that created a predominantly Calvinist national kirk, which was strongly Presbyterian in outlook. A confession of faith, rejecting papal jurisdiction and the mass, was adopted by Parliament in 1560.[20] The kirk found it difficult to penetrate the Highlands and Islands, but began a gradual process of conversion and consolidation that, compared with reformations elsewhere, was conducted with relatively little persecution.[21] James VI of Scotland favoured doctrinal Calvinism but supported the bishops.[22] Charles I of England brought in reforms seen by some as a return to papal practice. The result was the Bishop's Wars in 1639–40, ending in virtual independence for Scotland and the establishment of a fully Presbyterian system by the dominant Covenanters.[23] After the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Scotland regained its kirk, but also the bishops.[24] Particularly in the south-west many of the people began to attend illegal field conventicles. Suppression of these assemblies in the 1680s was known as "the Killing Time". After the "Glorious Revolution" in 1688, Presbyterianism was restored.[25]

The Church of Scotland had been created in the Reformation. Then the late 18th century saw the beginnings of its fragmentation around issues of government and patronage, but also reflecting a wider division between the Evangelicals and the Moderate Party.[26] In 1733 the First Secession led to the creation of a series of secessionist churches, and the second in 1761 to the foundation of the independent Relief Church.[26] These churches gained strength in the Evangelical Revival of the later 18th century.[27] Penetration of the Highlands and Islands remained limited. The efforts of the Kirk were supplemented by missionaries of the SSPCK, the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge.[28] Episcopalianism retained supporters, but declined because of its associations with Jacobitism.[26] Beginning in 1834 the "Ten Years' Conflict" ended in a schism from the church, led by Dr Thomas Chalmers, known as the Great Disruption of 1843. Roughly a third of the clergy, mainly from the North and Highlands, formed the separate Free Church of Scotland. The evangelical Free Churches grew rapidly in the Highlands and Islands.[28] In the late 19th century, major debates, between fundamentalist Calvinists and theological liberals, resulted in a further split in the Free Church as the rigid Calvinists broke away to form the Free Presbyterian Church in 1893.[26]

From this point there were moves towards reunion, and most of the Free Church rejoined the Church of Scotland in 1929. The schisms left small denominations including the Free Presbyterians and a remnant that had not merged in 1900 as the Free Church.[26] Catholic Emancipation in 1829 and the influx of large numbers of Irish immigrants led to an expansion of Catholicism, with the restoration of the Church hierarchy in 1878. Episcopalianism also revived in the 19th century; the Episcopal Church in Scotland was organised as an autonomous body in communion with the Church of England in 1804.[26] Other denominations included Baptists, Congregationalists, and Methodists.[26] In the twentieth century, existing Christian denominations were joined by the Brethren and Pentecostal churches. Although some denominations thrived, after World War II there was a steady overall decline in church attendance and resulting church closures in most denominations.[27]

Christianity

[edit]Protestantism

[edit]Church of Scotland (Presbyterian)

[edit]

The British Parliament passed the Church of Scotland Act 1921, recognising the full independence of the church in matters spiritual, and as a result of this and passage of the Church of Scotland (Property and Endowments) Act, 1925, which settled the issue of patronage in the church, the Church of Scotland was able to unite with the United Free Church of Scotland in 1929. The United Free Church of Scotland was itself the product of the union of the former United Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the majority of the Free Church of Scotland in 1900.[26] The 1921 Act recognised the kirk as the national church and the monarch became an ordinary member of the Church of Scotland, represented at the General Assembly by their Lord High Commissioner.[29][30]

In the second half of the 20th century and afterwards the Church was particularly affected by the general decline in church attendance. Between 1966 and 2006 numbers of communicants in the Church of Scotland dropped from over 1,230,000 to 504,000.[31] Formal membership reduced from 446,000 in 2010 to 398,389 or 7.5% of the total population by year end 2013,[32] dropping to 325,695 by year end 2018 and representing about 6% of the Scottish population.[33] By 2020, membership had fallen further to 297,345 or 5% of the total population.[34] As at December 2021 there were 283,600 members of the Church of Scotland, a fall of 4.6% from 2020. In the ten years period (2011-2021) the number of members has fallen by 34%.[35] As at December 2022, there were 270,300 members of the Church of Scotland.[36] As at December 2023, there were 259,200 members of the Church of Scotland, a fall of 4.1% from 2022. In the last ten years, since 2013, the number of members has fallen by 35%.[37]

In 2016, the actual weekly attendance at a Kirk service was estimated to be 136,910.[38]: 16 In the twenty-first century the Church has faced financial issues, with a £5.7 million deficit in 2010. In response the church adopted a "prune to grow" policy, cutting 100 posts and introducing job-shares and unpaid ordained staff.[39] In the 2022 national census, 20.4% of Scots identified their religion as "Church of Scotland", which aligns with a 2019 Scottish Household Survey with showed 20% of Scots self-reported themselves as adherents.[40][41] By 2023, the Church estimated that around 60,000 people worshipped in church on a Sunday, a drop from 88,000 before the Covid pandemic.[42]

Other Presbyterian denominations

[edit]After the reunification of the Church of Scotland and the United Free Church, some independent Scottish Presbyterian denominations still remained. These included the Free Church of Scotland (formed of those congregations which refused to unite with the United Presbyterian Church in 1900), the United Free Church of Scotland (formed of congregations which refused to unite with the Church of Scotland in 1929), the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland, the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland (which broke from the Free Church of Scotland in 1893), the Associated Presbyterian Churches (which emerged as a result of a split in the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland in the 1980s), and the Free Church of Scotland (Continuing) (which emerged from a split in the Free Church of Scotland in 2000).[43] In recent years, four congregations of the International Presbyterian Church have also arisen in Scotland, all founded as a result of evangelicals leaving the Church of Scotland over recent issues.[44] In addition, there are two congregations belonging to the Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster located in Scotland.[45] Similarly, five former Church of Scotland congregations have partnered together within the 'Didasko Presbytery' (Cornerstone Community Church, Stirling; Edinburgh North Church; Gilcomston Church, Aberdeen; Grace Church, Dundee; and The Tron Church, Glasgow).[46][47][48] [49] Thus, there are 10 Presbyterian denominations represented within Scotland.

At the 2011 census, 3,553 people responded as Other Christian – Presbyterian (i.e. not Church of Scotland), 1,197 as Other Christian – Free Presbyterian, 313 as Other Christian – Evangelical Presbyterian Church, and as few as 12 people as Other Christian – Scottish Presbyterianism. Those identifying with a particular Presbyterian denomination other than the Church of Scotland were:[8]

| Denomination | 1994 Sunday church attendance (Scottish Church Census) |

2002 Sunday church attendance (Scottish Church Census) |

2011 People identifying (National census)[8] |

2016 Sunday church attendance (Scottish Church Census)[38]: 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free Church of Scotland | 15,510 | 12,810 | 10,896 | 10,210 |

| United Free Church of Scotland | 5,840 | 5,370 | 1,514 | 3,220 |

| Free Church of Scotland (Continuing) | Not yet split from FCofS | 1,520 | 830 | |

| Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland | 132 | |||

| Reformed Presbyterian Church | 57 | |||

| Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster | 14 | |||

| Presbyterian Church in Ireland | 11 |

Free Church of Scotland

[edit]The second largest Presbyterian denomination in Scotland is the Free Church of Scotland with 10,896 people identifying as being of that church at the 2011 census.[8] According to the Free Church, its average weekly attendance at a worship service is around 13,000.[50] According to the 2016 Church Census, Free Church attendance was around 10,000 per week and amounted to 7% of all Presbyterian church attendance in Scotland.[38]: 18 As of 2016 there were 102 Free Church congregations, organised into six presbyteries.[51] A significant proportion of Free Church activity is to be found in the Highlands and Islands.[52]

Scottish Episcopal Church

[edit]The Scottish Episcopal Church is the member church of the Anglican Communion in Scotland. It is made up of seven dioceses, each with its own bishop.[53] It dates from the Glorious Revolution in 1689 when the national church was defined as presbyterian instead of episcopal in government. The bishops and those that followed them became the Scottish Episcopal Church.[54]

Scotland's third largest church,[55] the Scottish Episcopal Church has 303 local congregations.[56] In terms of official membership, Episcopalians nowadays constitute well under 1 per cent of the population of Scotland, making them considerably smaller than the Church of Scotland that represents nearly 5 per cent of the Scottish population.

The all-age membership of the church in 2022 was 23,503 of whom 16,605 were communicant members. Weekly attendance was 8,815.[57] The all-age membership of the church in 2018 was 28,647, of whom 19,983 were communicant members. Weekly attendance was 12,430.[58][59] For 2013, the Scottish Episcopal Church reported its numbers as 34,119 members (all ages).[60]

Other Protestant denominations

[edit]Other Protestant denominations which entered Scotland, usually from England, before the 20th century included the Quakers, Baptists, Methodists and Brethren. By 1907 the Open Brethren had 196 meetings and by 1960 it was 350, with perhaps 25,000 people. The smaller Exclusive Brethren had perhaps another 3,000. Both were geographically and socially diverse, but particularly recruited in fishing communities in the Islands and East.[43] In the 2011 census 5,583 identified themselves as Brethren, 10,979 as Methodist, 1,339 as Quaker, 26,224 as Baptist, and 13,229 as Evangelical.[8]

Pentecostal churches were present from 1908 and by the 1920s there were three streams: Elim, Assemblies of God and the Apostolic Church. A Holiness movement, inspired by Methodism, emerged in 1909 and by 1915 was part of the American Church of the Nazarene. The 2011 census lists 12,357 Pentecostals and 785 Church of the Nazarene.[8][61]

Catholicism

[edit]

During much of the 20th century and beyond, significant numbers of Catholics emigrated to Scotland from Italy, Lithuania,[62] and Poland.[63] According to the catholic Bishops' Conference of Scotland, there were 676.000 Catholics in 2023.[64]

However, the church has been affected by the general decline in churchgoing. Between 1994 and 2002 Catholic attendance in Scotland declined 19%, to just over 200,000.[65] By 2008, the Bishops' Conference of Scotland estimated that 184,283 attended mass regularly in that year: 3.6% of Scotland's population.[66] According to the 2011 census, Catholics comprise 15.9% of the overall population.[67] In 2011, Catholics outnumbered adherents of the Church of Scotland in just four of the council areas, including North Lanarkshire, Inverclyde, West Dunbartonshire, and the most populous council, Glasgow City.[68] According to the 2019 Scottish Household Survey, 13% of the adult Scottish population identified with Catholicism.[69]

In February 2013, Cardinal Keith O'Brien resigned as Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh after allegations of sexual misconduct against him.[70] Subsequently, there were several other cases of alleged sexual misconduct involving other priests.[71] O'Brien was replaced as Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh by Leo Cushley.

Orthodoxy

[edit]The various branches of Orthodox Christianity (including Russian, Greek, and Coptic) had around 8,900 respondents at the 2011 census.[8]

Non-Trinitarian denominations

[edit]Non-Trinitarian denominations such as the Jehovah's Witnesses with 8,543 respondents in the 2011 census and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with 4,651[8] are also present in Scotland. However, the LDS Church claims a much higher number of followers with their own 2009 numbers listing 26,536 followers (in 27 wards and 14 branches).[72]

Islam

[edit]

Islam is the second most followed religion after Christianity in Scotland. The first Muslim student in Scotland was Wazir Beg from Bombay (now Mumbai). He is recorded as being a medical student who studied at the University of Edinburgh between 1858 and 1859.[73] The production of goods and Glasgow's busy port meant that many lascars were employed there. Dundee was at the peak of importing jute; hence, sailors from Bengal were a feature at the port. The 1903 records from the Glasgow Sailors' Home show that nearly a third (5,500) of all boarders were Muslim lascars. Most immigration of Muslims to Scotland is relatively recent. The bulk of Muslims in Scotland come from families who immigrated during the late 20th century, with small numbers of converts.[74] In 2022 Muslims represented 2.2 per cent of the Scottish population (119,872, up from 76,737 in 2011). Two important mosques in Scotland are Glasgow Central Mosque and Edinburgh Central Mosque, which took more than six years to complete at a cost of £3.5m[75] and can accommodate over one thousand worshippers in its main hall.[76]

Judaism

[edit]

Towards the end of the nineteenth century there was an influx of Jews, most from eastern Europe, escaping poverty and persecution. Many were skilled in the tailoring, furniture, and fur trades and congregated in the working class districts of Lowland urban centres, like the Gorbals in Glasgow. The largest community in Glasgow had perhaps reached 5,000 by the end of the century.[43] A synagogue was built at Garnethill in 1879. Over 8,000 Jews were resident in Scotland in 1903.[77] Refugees from Nazism and the Second World War further augmented the Scottish Jewish community, which has been estimated to have reached 80,000 in the middle of the century.[78]

According to the 2001 census, approximately 6,400 Jews lived in Scotland, however by the 2011 census this had fallen to 5,887.[7] Scotland's Jewish population continues to be predominantly urban, with 80 per cent resident in the areas surrounding Glasgow,[79] primarily East Renfrewshire, that area in particular containing 41% of Scotland's Jewish population, despite only containing 1.7% of the overall population. As with Christianity, the practising Jewish population continues to fall, as many younger Jews either become secular or intermarry with other faiths.[citation needed] Scottish Jews have also emigrated in large numbers to the US, England, and the Commonwealth for economic reasons, as with other Scots.[citation needed]

The formally organised Jewish communities in Scotland now include Glasgow Jewish Representative Council, Edinburgh Hebrew congregation and Sukkat Shalom Liberal Community, Aberdeen Synagogue and Jewish Community Centre, and Tayside and Fife Jewish Community. These are all represented by the Scottish Council of Jewish Communities, alongside groups like the Jewish Network of Argyll and the Highlands, Jewish students studying in Scottish universities and colleges, and Jewish people of Israeli origin living in Scotland.

Sikhism

[edit]According to the 2022 census, Sikhism represented 0.2% of the Scotland's population (10,988). Maharajah Duleep Singh moved to Scotland in 1854, taking up residence at the Grandtully estate in Perthshire.[80] According to the Scottish Sikh Association, the first Sikhs settled in Glasgow in the early 1920s with the first Gurdwara established on South Portland Street.[81] However, the bulk of Sikhs in Scotland come from families who immigrated during the late 20th century.

Hinduism

[edit]According to the 2022 census, 29,929 people identified as Hindu, representing 0.6% of the population of Scotland. The bulk of Scottish Hindus settled there in the second half of the 20th century. At the 2001 Census, 5,600 people identified as Hindu, which then equated to 0.1% of the Scottish population.[6] Most Scottish Hindus are of Indian origin, or at least from neighbouring countries such as Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh. Many of these came after Idi Amin's expulsion from Uganda in the 1970s, and some also came from South Africa. There are also a few of Indonesian and Afghan origin. In 2006 a temple opened in the West End of Glasgow.[82] However, it was severely damaged by a fire in May 2010.[83] The ISKCON aka "Hare Krishna" also operates out of Lesmahagow in South Lanarkshire. There are also temples in Edinburgh and Dundee with plans announced in 2008 for a temple in Aberdeen.[84]

Buddhism

[edit]According to the 2022 census, 15,501 people in Scotland—0.3 per cent—are Buddhist.[85]

Modern Paganism

[edit]Modern Pagan religions such as Wicca, Neo-druidism, and Celtic Reconstructionist Paganism have their origins in academic interest and romantic revivalism, which emerged in new religious movements in the twentieth century.[86] Gerald Gardner, a retired British civil servant, founded modern Wicca. He cultivated his Scottish connections and initiated his first Scottish followers in the 1950s.[87] The Findhorn community, founded in 1962 by Peter and Eileen Caddy, became a centre of a variety of new age beliefs that mixed beliefs including occultism, animism, and eastern religious beliefs.[88] The ancient architectural landscape of pre-Christian Britain, such as stone circles and dolmens, gives pagan beliefs an attraction, identity, and nationalist legitimacy.[89] The rise of pan-Celticism may also have increased the attractiveness of Celtic neopaganism.[90] In the 2011 census 5,282 identified as Pagan or a related belief.[8] The Scottish Pagan Federation has represented Modern Pagans in Scotland since 2006.[91]

Bahá'í Faith

[edit]Scotland's Baháʼí history began around 1905 when European visitors, Scots among them, met `Abdu'l-Bahá, then head of the religion, in Ottoman Palestine.[92] One of the first and most prominent Scots who became a Baháʼí was John Esslemont (1874–1925). Starting in the 1940s a process of promulgating the religion called pioneering by Baháʼís began for the purpose of teaching the religion.[93] This led to new converts and establishment of local Spiritual Assemblies, and eventually a Baháʼí Council for all Scotland was elected under the National Assembly of the Baháʼís of the United Kingdom. According to the 2011 Census in Scotland, 459 people living there declared themselves to be Bahá'ís,[8] compared to a 2004 figure of approximately 5,000 Baháʼís in the United Kingdom.[94]

Irreligion

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 1,394,460 | — |

| 2011 | 1,941,116 | +39.2% |

| 2022[5] | 2,780,900 | +43.3% |

| Religious Affiliation was not recorded prior to 2001. | ||

Ethnicity

[edit]The table shows the irreligious populations among ethnic groups and nationalities in Scotland.

| Ethnic group | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | % of Ethnic group reported No Religion | |

| – Scottish | 2,267,031 | 53.63 |

| – British | 289,876 | 56.80 |

| – Irish | 18,764 | 32.99 |

| – Polish | 24,312 | 26.79 |

| – Gypsy and Irish Traveller | 1,496 | 44.75 |

| – Roma | 919 | 24.00 |

| – Other White | 76,584 | 46.81 |

| – Mixed | 33,090 | 54.34 |

| – Indian | 4,823 | 9.11 |

| – Pakistani | 3,389 | 4.65 |

| – Bangladeshi | 515 | 7.43 |

| – Chinese | 34,762 | 73.84 |

| – Other Asian | 7,302 | 22.69 |

| – African | 5,366 | 9.15 |

| – Caribbean or Black | 2,611 | 38.52 |

| – Arab | 2,057 | 9.22 |

| – Other Ethnic group | 7,254 | 26.54 |

| TOTAL | 2,780,900 | 51.1 |

Religious leaders

[edit]- Church of Scotland: The Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland convenes the annual assembly, but does not "lead", the church. Moderators are limited to serving one year in office. The moderator-designate is nominated in October and takes office in the following May. The moderator for 2019-2020 was Colin Sinclair of Palmerston Place Church, Edinburgh. The moderator for 2020-2021 was Martin Fair of St Andrews Parish Church, Arbroath.

- Catholic Church in Scotland: Leo Cushley, Archbishop of St Andrews and Edinburgh (see Bishops' Conference of Scotland, installed 8 September 2013).

- Scottish Episcopal Church: The Presiding Bishop of the Scottish Episcopal Church is called the Primus. The current Primus is Mark Strange, Diocese of Moray, Ross and Caithness, who has held the role since 27 June 2017.

- Free Church of Scotland: The Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland for 2016/17 is the Rev. John Nicholls, a minister at the Smithon Free Church and a former chief executive of the London City Mission.[96]

- Free Church of Scotland (Continuing): The current Moderator of the General Assembly of the Free Church of Scotland (Continuing) is the Rev. James I. Gracie who is the minister in Edinburgh.

- Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland: The current Moderator of Synod for the Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland is the Rev. D Campbell.

- Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland: The Moderator of the RPCS is the Rev. Gerald Milligan from Stranraer.

Religious issues

[edit]Sectarianism

[edit]

Sectarianism became a serious problem in the twentieth century. In the interwar period religious and ethnic tensions between Protestants and Catholics were exacerbated by the Great Depression. Tensions were heightened by the leaders of the Church of Scotland who orchestrated a racist campaign against the Catholic Irish in Scotland.[97] Key figures leading the campaign were George Malcolm Thomson and Andrew Dewar Gibb. This focused on the threat to the "Scottish race" based on spurious statistics that continued to have influence despite being discredited by official figures in the early 1930s. This created a climate of intolerance that led to calls for jobs to be preserved for Protestants.[98] After the Second World War the Church became increasingly liberal in attitude and moved away from hostile attitudes. Sectarian attitudes continued to manifest themselves in football rivalries between predominantly Protestant and Catholic teams. This was most marked in Glasgow with the traditionally Catholic team, Celtic, and the traditionally Protestant team, Rangers. Celtic employed Protestant players and managers, but Rangers have had a tradition of not recruiting Catholics.[99][100] This is not a hard and fast rule, however, as evidenced by Rangers signing of the Catholic player Mo Johnston (born 1963) in 1989 and in 1999 their first Catholic captain, Lorenzo Amoruso.[101][102]

From the 1980s the UK government passed several acts that had a provision concerning sectarian violence. These included the Public Order Act 1986, which introduced offences relating to the incitement of racial hatred, and the Crime and Disorder Act 1998, which introduced offences of pursuing a racially aggravated course of conduct that amounts to harassment of a person. The 1998 Act also required courts to take into account where offences are racially motivated, when determining sentence. In the twenty-first century the Scottish Parliament legislated against sectarianism. This included provision for religiously aggravated offences in the Criminal Justice (Scotland) Act 2003. The Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Act 2010 strengthened statutory aggravations for racial and religiously motivated crimes. The Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012 criminalised behaviour which is threatening, hateful, or otherwise offensive at a regulated football match including offensive singing or chanting. It also criminalised the communication of threats of serious violence and threats intended to incite religious hatred.[103]

Ecumenism

[edit]

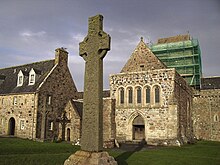

Relations between Scotland's churches steadily improved during the second half of the twentieth century and there were several initiatives for co-operation, recognition, and union. The Scottish Council of Churches was formed as an ecumenical body in 1924.[104] The foundation of the ecumenical Iona Community in 1938, on the island of Iona off the coast of Scotland, led to a highly influential form of music, which was used across Britain and the US. Leading musical figure John Bell (born 1949) adapted folk tunes or created tunes in a folk style to fit lyrics that often emerged from the spiritual experience of the community.[105] Proposals in 1957 for union with the Church of England were rejected over the issue of bishops and were severely attacked in the Scottish press. The Scottish Episcopal church opened the communion table up to all baptised and communicant members of all the trinitarian churches and church canons were altered to allow the interchangeability of ministers within specific local ecumenical partnerships.[106]

The Dunblane consultations, informal meetings at the ecumenical Scottish Church House in Dunblane in 1961–69, attempted to produce modern hymns that retained theological integrity. They resulted in the British "Hymn Explosion" of the 1960s, which produced multiple collections of new hymns.[107] In 1990, the Scottish Churches' Council was dissolved and replaced by Action of Churches Together in Scotland (ACTS), which attempted to bring churches together to set up ecumenical teams in the areas of prisons, hospitals, higher education, and social ministries and inner city projects.[108] At the end of the twentieth century the Scottish Churches Initiative for Union (SCIFU), between the Episcopal Church, the Church of Scotland, the Methodist Church, and the United Reformed Church, put forward an initiative whereby there would have been mutual recognition of all ordinations and that subsequent ordinations would have satisfied episcopal requirements, but this was rejected by the General Assembly in 2003.[106]

Irreligion

[edit]Church attendance in all denominations declined after the First World War. By the 1920s roughly half the population had a relationship with one of the Christian denominations. This level was maintained until the 1940s when it dipped to 40% during the Second World War, but it increased in the 1950s as a result of revivalist preaching campaigns, particularly the 1955 tour by Billy Graham, and returned to almost pre-war levels. However, from that point there was a steady decline and by the 1980s it was just over 30%. The decline most affected urban areas and was most noticeable among the traditional skilled working classes and educated working classes, although participation stayed higher in the Catholic Church than the Protestant denominations.[98]

In the 2022 Census, 51.1% of the population identified as 'None' with respect to religious affiliation (in the 2011 census 36.7% had stated they had no religion,[7] while 5.5 per cent did not state a religion. In 2001, 27.5% had stated that they had no religion; compared with 15.5% in the UK overall).[6][109] A study carried out on behalf of the British Humanist Association at the same time as the 2011 census suggested that those not identifying with a denomination, or who saw themselves as non-religious, may have been much higher at between 42 and 56 per cent, depending on the form of the question asked.[110]

In 2016 the Scottish Social Attitudes Survey found that 52% of people said they are not religious. The decline was most rapid in the Church of Scotland, from 35% in 1999 to 20%, while the Catholic (15%) and other Christian (11%) affiliations remained steady, In 2017, the Humanist Society Scotland commissioned a survey of Scottish residents 16 years and older, asking the question "Are you religious?" Of the 1,016 respondents, 72.4% responded no, 23.6% said yes, and 4% did not answer.[111]

Church attendance has also declined, with two-thirds of people living in Scotland saying they "never or practically never" attend services, compared with 49% when the survey began.[112] Since 2016, humanists in Scotland have conducted more marriages each year than the Church of Scotland (or any other religious denomination).[3][113]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Scotland's Census – religion, ethnic group, language and national identity results". Scotland's Census. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ "Scottish Episcopal Church could be first in UK to conduct same-sex weddings". Scottish Legal News. 20 May 2016. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ a b "More than 4200 Humanist weddings took place in Scotland last year". Humanist Society Scotland. August 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Thomas, Greg (20 July 2023). "Far more humanist weddings than Christian ceremonies in 2022: National Records of Scotland". Humanist Society Scotland. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ a b "Scotland's Census 2022 - Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion". 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024.

- ^ a b c "Analysis of Religion in the 2001 Census". The Scottish Government. 17 May 2006. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ a b c "Scotland's Census 2011 – Table KS209SCb" (PDF). Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 26 September 2013..

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Religion (detailed)" (PDF). Scotland's Census 2011. National Records of Scotland. Retrieved 12 April 2015. The census choices were None, Church of Scotland, Roman Catholic, Other Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Sikh, Jewish, Hindu, and Another religion or body. Those answering Other Christian or Another religion were asked to write which one.

- ^ "Scotland's Census 2022 - Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion - Chart data". Scotland's Census. National Records of Scotland. 21 May 2024. Retrieved 21 May 2024. Alternative URL 'Search data by location' > 'All of Scotland' > 'Ethnic group, national identity, language and religion' > 'Religion'

- ^ L. Alcock, Kings and Warriors, Craftsmen and Priests in Northern Britain AD 550–850 (Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland), ISBN 0-903903-24-5, p. 63.

- ^ Lucas Quensel von Kalben, "The British Church and the Emergence of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom", in T. Dickinson and D. Griffiths, eds, Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History, 10: Papers for the 47th Sachsensymposium, York, September 1996 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), ISBN 086054138X, p. 93.

- ^ R. A. Fletcher, The Barbarian Conversion: from Paganism to Christianity, (Berkeley CA: University of California Press, 1999), ISBN 0520218590, pp. 79–80.

- ^ B. Webster, Medieval Scotland: the Making of an Identity (New York City, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1997), ISBN 0333567617, pp. 53–4.

- ^ a b A. Macquarrie, Medieval Scotland: Kinship and Nation (Thrupp: Sutton, 2004), ISBN 0-7509-2977-4, pp. 117–128.

- ^ a b P. J. Bawcutt and J. H. Williams, A Companion to Medieval Scottish Poetry (Woodbridge: Brewer, 2006), ISBN 1843840960, pp. 26–9.

- ^ a b J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 76–87.

- ^ Andrew D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 052158602X, p. 246.

- ^ C. Peters, Women in Early Modern Britain, 1450–1640 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), ISBN 033363358X, p. 147.

- ^ Andrew D. M. Barrell, Medieval Scotland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000), ISBN 052158602X, p. 257.

- ^ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 120–1.

- ^ J. Wormald, Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1991), ISBN 0748602763, pp. 121–33.

- ^ R. Mitchison, A History of Scotland (London: Routledge, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0415278805, pp. 166–8.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 205–6.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 231–4.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, p. 241.

- ^ a b c d e f g h J. T. Koch, Celtic Culture: a Historical Encyclopedia, Volumes 1–5 (London: ABC-CLIO, 2006), ISBN 1-85109-440-7, pp. 416–7.

- ^ a b G. M. Ditchfield, The Evangelical Revival (1998), p. 91.

- ^ a b G. Robb, "Popular Religion and the Christianisation of the Scottish Highlands in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries", Journal of Religious History, 1990, 16(1), pp. 18–34.

- ^ "Queen and the Church". The British Monarchy (Official Website). Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

- ^ "How we are organised". Church of Scotland. 22 February 2010. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 4 August 2011.

- ^ Church of Scotland 2007–2008 Year Book, p. 350.

- ^ "Church of Scotland 'struggling to stay alive'". www.scotsman.com.

- ^ COUNCIL OF ASSEMBLY MAY 2019

- ^ "Church of Scotland General Assembly 2021 CONGREGATIONAL STATISTICS 2020 Summary Page 75" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 27 April 2022.

- ^ SUPPLEMENTARY REPORT OF THE ASSEMBLY TRUSTEES MAY 2022 - CONGREGATIONAL STATISTICS page 37

- ^ SUPPLEMENTARY REPORT OF THE ASSEMBLY TRUSTEES MAY 2023 - CONGREGATIONAL STATISTICS page 31

- ^ REPORT OF THE ASSEMBLY 2024 - CONGREGATIONAL STATISTICS page 20

- ^ a b c Brierley, Peter (2016). The Fourth Scottish Church Census: The Results Unveiled (PDF). Retrieved 21 May 2017.

- ^ "New Moderator backs cuts to trim Church of Scotland £5.7m debt", The Scotsman. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ "Scottish household survey 2019: key findings". www.gov.scot. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ "Scotland's People Annual Report: Key Findings" (PDF). www.gov.scot. 15 September 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2020. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ "Hundreds of churches will have to close, says Kirk". BBC News. 19 May 2023.

- ^ a b c C. G. Brown, Religion and Society in Scotland Since 1707 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1997) ISBN 0748608869, p. 38.

- ^ "International Presbyterian Church". International Presbyterian Church. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- ^ "Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster – Churches". Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Our Corporate members". Affinity. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "New to the Tron?". The Tron Church. Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Didasko Presbytery Document" (PDF). Retrieved 13 November 2023.

- ^ "Didasko Presbytery". Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "About". Free Church of Scotland. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2017.

- ^ Free Church of Scotland Yearbook 2016 (PDF). Edinburgh: Free Church of Scotland.

- ^ <staff writer> (2016). "Free Church of Scotland". Encyclopædia Britannica (On-line ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ^ I. S. Markham, J. Barney Hawkins, IV, J. Terry and L. N. Steffensen, eds, The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion (London: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), ISBN 1118320867.

- ^ J. D. Mackie, B. Lenman and G. Parker, A History of Scotland (London: Penguin, 1991), ISBN 0140136495, pp. 252–3.

- ^ "Scottish Episcopal Church could be first in UK to conduct same-sex weddings". Scottish Legal News. 20 May 2016. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- ^ "Scottish Church Census" (PDF). Brierley Consultancy. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ BRIN Counting Religion - referring to the Scottish Episcopal Church 41st Annual Report

- ^ Scottish Episcopal Church 36th Annual Report

- ^ "35th Annual Report and Accounts SEC" (PDF). The Scottish Episcopal Church. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ 31st Annual Report (PDF). Scottish Episcopal Church. 2014. p. 65. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- ^ D. W. Bebbington, "Protestant sects and disestablishment" in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 494–5.

- ^ "Legacies – Immigration and Emigration – Scotland – Strathclyde – Lithuanians in Lanarkshire". BBC. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ A. Collier "Scotland's confident Catholics", Tablet 10 January 2009, p. 16.

- ^ [1]

- ^ Tad Turski (1 February 2011). "Statistics". Dioceseofaberdeen.org. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 18 December 2011.

- ^ "How many Catholics are there in Britain?". BBC News. 15 September 2010. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ^ "Census reveals huge rise in number of non-religious Scots", Brian Donnelly, The Herald (Glasgow), 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Religion by council area, Scotland, 2011". Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- ^ "Section Two - Household Characteristics". www.gov.scot. Retrieved 11 January 2024.

- ^ Pigott, Robert (25 February 2013). "Cardinal Keith O'Brien resigns as Archbishop". BBC. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ Catherine Deveney (6 April 2013). "Catholic priests unmasked: 'God doesn't like boys who cry' | The Observer". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ "Country information: United Kingdom", Church News Online Almanac, 1 February 2010, retrieved 17 September 2016

- ^ Resources, ideas and information for anti-sectarian and religious equality education

- ^ S. Gilliat-Ray, Muslims in Britain (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), ISBN 052153688X, p. 118.

- ^ "Edinburgh mosque opens". BBC News. 31 July 1998. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

- ^ "Muslim Directory". Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ^ W. Moffat, A History of Scotland: Modern Times (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989), ISBN 0199170630, p. 38.

- ^ Macleod, Murdo (20 August 2006). "Rockets can't keep Scots from their Israeli roots". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 6 June 2014.

- ^ S. Bruce, Scottish Gods: Religion in Modern Scotland, 1900–2012 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014), ISBN 0748682899, p. 14.

- ^ On the trail of the Sikh heritage BBC News, 30 September 2008

- ^ Introduction scottishsikhs.com. Retrieved 13 January 2009

- ^ New Hindu temple opens in Glasgow BBC News, 19 July 2006

- ^ Fire severely damages Hindu temple in Glasgow BBC, 30 May 2010

- ^ Hindu temple planned for Aberdeen BBC News, 22 September 2008.

- ^ "2011 Census: Key Results from Releases 2A to 2D" (PDF).

- ^ N. J. R. Lewis, ed., The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), ISBN 0199708754, p. 515.

- ^ M. Howard, Modern Wicca (Llewellyn Worldwide, 2010), ISBN 073872288X, p. 10.

- ^ D. Groothuis, Unmasking the New Age (InterVarsity Press, 1986), ISBN 0877845689, pp. 137–8.

- ^ R. L. Winzeler, Anthropology and Religion: What We Know, Think, and Question (Rowman & Littlefield, 2012), ISBN 0759121893, p. 174.

- ^ M. Bowman, "Contemporary Celtic spirituality", in A. Hale and P. Payton, eds, "New Directions in Celtic Studies" (Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2000), ISBN 0859895874, pp. 61–80.

- ^ "What is the SPF?". The Scottish Pagan Federation. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- ^ Weinberg, Robert; Bahá'í International Community (27 January 2005). "History springs to life on Scottish stage". Bahá'í World News Service.

- ^ U.K. Bahá'í Heritage Site. "The Bahá'í Faith in the United Kingdom – A Brief History". Archived from the original on 26 February 2008. Retrieved 18 February 2008.

- ^ "In the United Kingdom, Bahá'ís promote a dialogue on diversity". One Country. 16 (2). July–September 2004.

- ^ Data taken from [https://www.scotlandscensus.gov.uk/webapi/jsf/tableView/tableView.xhtml

- ^ "New Free Church Moderator is Inverness minister". Press and Journal. 9 October 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2016.

- ^ "The legacy of a notorious campaign – Open House Scotland". 6 November 2013.

- ^ a b R. J. Finley, "Secularization" in M. Lynch, ed., The Oxford Companion to Scottish History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), ISBN 0-19-211696-7, pp. 516–17.

- ^ C. Brown, The Social History of Religion in Scotland Since, 1730 (London: Routledge, 1987), ISBN 0416369804, p. 243.

- ^ Giulianotti, Richard (1999). Football: A Sociology of the Global Game. John Wiley & Sons. p. 18. ISBN 9780745617695.

Historically Rangers have maintained a staunch Protestant and anti-Catholic tradition which includes a ban on signing Catholic players.

- ^ Laing, Allan (11 July 1989). "Ibrox lands double coup with Johnston". The Glasgow Herald. p. 1. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ Stanco, Sergio (30 August 2017). "Lorenzo Amoruso: Joining Rangers was 'an opportunity I couldn't miss'". Planet Football. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

Amoruso was made captain by Advocaat, becoming the first ever Catholic player to skipper Rangers, a Protestant club

- ^ "Action to tackle hate crime and sectarianism" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Scottish Government. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ B. Talbot, 1 "Baptists and other Christian Churches in the first half of the Twentieth Century" (2009). Retrieved 30 May 2014.

- ^ D. W. Music, Christian Hymnody in Twentieth-Century Britain and America: an Annotated Bibliography (London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001), ISBN 0313309035, p. 10.

- ^ a b Ian S. Markham, J. Barney Hawkins, IV, Justyn Terry, Leslie Nuñez Steffensen, eds, The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to the Anglican Communion (Oxford: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), ISBN 1118320867.

- ^ D. W. Music, Christian Hymnody in Twentieth-Century Britain and America: an Annotated Bibliography (London: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001), ISBN 0313309035, p. 3.

- ^ Robert C. Lodwick, Remembering the Future: The Challenge of the Churches in Europe (Friendship Press, 1995), ISBN 0377002909, p. 16.

- ^ "Religious Populations", Office for National Statistics, 11 October 2004, archived from the original on 4 June 2011, retrieved 15 August 2011

- ^ J. McManus, "Two-thirds of Britons not religious, suggests survey", BBC NEWS UK, 21 March 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2014.

- ^ Humanist Society Scotland, [2], Issues Poll", 14 September 2017. Retrieved 28 September 2017.

- ^ "Most people in Scotland 'not religious'", BBC News, 3 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ^ "Humanist weddings overtake Church of Scotland ceremonies". www.scotsman.com. August 2018. Retrieved 27 August 2020.

Sources

[edit]- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Church institutions: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Scotland, the 'Nennian' Recension of the Historia Brittonum and the Libor Bretnach in Simon Taylor (ed.), Kings, clerics and chronicles in Scotland 500–1297. Four Courts, Dublin, 2000. ISBN 1-85182-516-9

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Nechtan son of Derile" in Lynch (2001).

- Clancy, Thomas Owen, "Columba, Adomnán and the Cult of Saints in Scotland" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

- Cross, F.L. and Livingstone, E.A. (eds), Scotland, Christianity in in "The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church", pp. 1471–1473. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1997. ISBN 0-19-211655-X

- Foster, Sally M., Picts, Gaels, and Scots: Early Historic Scotland. Batsford, London, 2004. ISBN 0-7134-8874-3

- Hillis, Peter, The Barony of Glasgow, A Window onto Church and People in Nineteenth Century Scotland, Dunedin Academic Press, 2007.

- Markus, Fr. Gilbert, O.P., "Religious life: early medieval" in Lynch (2001).

- Markus, Fr. Gilbert, O.P., "Conversion to Christianity" in Lynch (2001).

- Pope, Robert (ed.), Religion and National Identity: Wales and Scotland, c.1700–2000 (2001)

- Taylor, Simon, "Seventh-century Iona abbots in Scottish place-names" in Broun & Clancy (1999).

External links

[edit]This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (June 2024) |

- Church of Scotland

- Congregational Federation

- Catholic Bishops' Conference of Scotland

- Free Church of Scotland

- Scottish Baptist Union

- Scottish Episcopal Church

- Free Church of Scotland (Continuing)

- Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland

- United Free Church of Scotland

- Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Scotland

- Humanist Society Scotland

- The Scottish Council of Jewish Communities

- The Virtual Jewish History Tour – Scotland

- Jewish Encyclopedia on Scotland

- Scottish Pagan Federation