Second impeachment inquiry into Andrew Johnson

| Second impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson | |

|---|---|

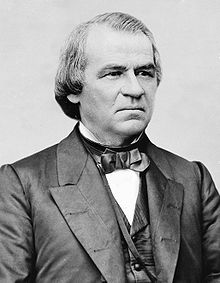

| Accused | Andrew Johnson, 17th President of the United States |

| Committee | Select Committee on Reconstruction |

| Committee chair | Thaddeus Stevens |

| Date | January 27– February 22, 1868 (3 weeks and 5 days) |

| Outcome | Select Committee on Reconstruction recommended impeachment and reported an impeachment resolution; Johnson subsequently impeached |

| Charges |

|

| Congressional votes | |

| House vote authorizing the inquiry | |

| Votes in favor | 99 |

| Votes against | 31 |

| Result | Approved |

| House Committee on Reconstruction vote on the impeachment resolution | |

| Votes in favor | 7 |

| Votes against | 2 |

| Result | Approved |

| The House afterwards voted on February 24, 1868 to impeach Andrew Johnson | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal 16th Vice President of the United States 17th President of the United States Vice presidential and Presidential campaigns Post-presidency Family  |

||

The second impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson was an impeachment inquiry against United States President Andrew Johnson. It followed a previous inquiry in 1867. The second inquiry, unlike the first (which was run by the House Committee on the Judiciary), was run by the House Select Committee on Reconstruction. The second inquiry ran from its authorization on January 27, 1868, until the House Select Committee on Reconstruction reported to Congress on February 22, 1868.

By early February, it appeared the prospect of an impeachment advancing was improbable. This changed when, on February 21, 1868, Johnson attempted to dismiss and replace Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in violation of the Tenure of Office Act. That day, an impeachment resolution was forwarded to the select committee. The following day, the select committee approved a slightly amended version of the resolution in a party-line 7–2 vote (with all Republican members voting in favor of the impeachment resolution and Democratic members voting against it). On February 24, 1868, the impeachment resolution was passed by the House, thereby impeaching Johnson. Johnson was later acquitted in his impeachment trial.

Background

[edit]

Some Radical Republicans had entertained the thought of impeaching President Andrew Johnson since as early as 1866.[1] However, the Republican Party was divided on the prospect of impeachment, with moderate Republicans in the party, who held a plurality, widely opposing it at this point.[1] The radicals were more in favor of impeachment, as their plans for strong reform in reconstruction were greatly imperiled by Johnson.[1]

Several attempts were made by Radical Republicans to initiate impeachment, but these were initially successfully rebuffed by moderate Republicans in party leadership.[1] Radical Republicans continued to seek Johnson's impeachment, introducing impeachment resolutions in spite of a rule put in place for the House Republican caucus by the moderate Republican leadership in December 1866 requiring that a majority of House Republicans House Committee on the Judiciary would be required to approve any measure regarding impeachment in party caucus prior to it being considered in the House.[1][2] Moderate Republicans often stifled these resolutions by referring them to committees, however.[2] On January 7, 1867, Benjamin F. Loan, John R. Kelso, and James Mitchell Ashley each introduced three separate impeachment resolutions against Johnson. the House refused to hold debate or vote on either Loan or Kelso's resolutions.[1] However, they did allow a vote on Ashley's impeachment-related resolution.[1] Unlike the other two impeachment bills introduced that day (which would have outright impeached Johnson), Ashley's bill offered a specific outline of how an impeachment process would proceed, and it did not start with an immediate impeachment. Rather than going to a direct vote on impeaching the president, his resolution would instruct the Judiciary Committee to "inquire into the official conduct of Andrew Johnson", investigating what it called Johnson's "corruptly used" powers, including his political appointments, pardons for ex-Confederates, and his vetoes of legislation.[1][3][4] The resolution passed in the House 108–39.[1][5] It was seen as offering Republicans a chance to register their displeasure with Johnson, without actually formally impeaching him.[1] This launched the first impeachment inquiry against Andrew Johnson. After the end of the 39th Congress, the first impeachment inquiry was renewed in the 40th Congress.[1] On November 25, 1867, the House Committee on the Judiciary voted to recommend impeachment.[3][6] However, when put to a full vote of the House, the House voted 57–108 against impeaching Johnson on December 7, 1867, with more Republicans voting against impeachment than for it.[7]

Vote authorizing the inquiry

[edit]

On January 27, 1868, Rufus P. Spalding moved that the rules be suspended so that he could present a resolution resolving,

that the Committee on Reconstruction be authorized to inquire what combinations have been made or attempted to be made to obstruct the due execution of the laws, and to that end the committee have power to send for persons and papers and to examine witnesses on oath, and report to this House what action, if any, they may deem necessary, and that said committee have leave to report at any time.[8][9]

The motion to allow consideration of the resolution was agreed to by a vote of 103–37,[8][10] and the House voted to approve the resolution by a vote of 99–31.[8][10] This launched a new inquiry into Johnson run by the Select Committee on Reconstruction.[8]

No Democrats voted for the resolution, while the only Republicans who cast votes against it were Elihu B. Washburne and William Windom.[10][11][12] 57 members were absent from the vote (39 Republicans, 17 Democrats, and 1 Conservative Republican). Additionally, Speaker Schuyler Colfax (a Republican) did not vote,[10][11] as House rules do not require the speaker to vote during ordinary legislative proceedings, unless their vote would be decisive or if the vote is being cast by ballot.[13]

| Inquiry authorization vote[10][11] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 27, 1868 | Party | Total votes | |||||

| Democratic | Republican | Conservative | Conservative Republican | Independent Republican | |||

| Yea |

0 | 97 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 99 | |

| Nay | 28 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 31 | |

| Vote | Vote total |

|---|---|

| "Yea" votes | |

| "Nay" votes | |

| Absent/not voting |

Membership of House Select Committee on Reconstruction during the inquiry

[edit]The following is a table of the members during the second session, during which the inquiry took place.[14]

| Members of the House Select Committee on Reconstruction during the second session of the 40th United States Congress[14][15] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Republican Party | Democratic Party | |

|

| |

When the House had previously voted in December 1867 (at the end of the first impeachment inquiry) on the impeachment resolution forwarded to it by the House Committee on the Judiciary, four of these select committee members (Republicans Boutwell, Farnsworth, Stevens, and Paine) had voted in support of impeaching Johnson, while five of these select committee members (Republicans Beaman, Bingham, Hulburd and Democrats Beck and Brooks) had voted against impeachment.[16]

Inquiry

[edit]

At the time of the inquiry, Radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens was chair of the House Select Committee on Reconstruction.[17] At the time of the inquiry, Stevens was of advanced age and poor health.[18]

The select committee also looked into correspondence between President Johnson and Ulysses S. Grant, particularly what orders Grant had been given by Johnson when Grant was his acting sectretary of war.[19][20] Grant came to a committee meeting on February 8, but was not examined.[20] In early February, heated letters between Grant and Johnson had been published in the press, adding further intrigue and fuel to the investigation.[21][22]

The select committee interviewed witnesses. One witness interviewed multiple times was Jerome B. Stillson, a reporter with the New York World who had conducted regular interviews with President Johnson.[23][24]

Stevens successfully persuaded the House to, on February 10, 1868, pass a resolution transferring all records from the previous impeachment inquiry and any further responsibility on impeachment away from the Committee on the Judiciary and to the Select Committee on Reconstruction.[25][26]

Initial rejection of impeachment

[edit]Stevens believed that the letters between Johnson and Grant that had been published in the press proved that Johnson had attempted to convince Grant to act in violation of the Tenure of Office Act.[26] In the morning of February 13, 1868, the select committee held a brief session. Stevens announced that he desired to test the subject of impeachment in the select committee, stating that he believed that the investigation had gone far enough and the time for action to be taken had come.[26][27] Stevens introduced to the select committee a resolution to impeach the president for high crimes and misdemeanors. The resolution did not specify what high crimes and misdemeanors had been committed.[27] Along with the resolution, he also presented the select committee with a report arguing for impeachment. The chief reason for impeaching Johnson given in the report was that Johnson had (allegedly) acted with intent to violate the Tenure of Office Act.[25][26][28]

John Bingham (R– OH), a moderate Republican, held the balance of power on the select committee.[26] Bingham motioned to lay on the table both the resolution, the report, and the discussion of impeachment. Stevens asked, before a vote, that the vote on the motion be recorded so that the nation would know who was in support of impeachment and who was not. In what Stevens had framed to be a de facto proxy vote on impeachment, three select committee members (Republicans Fernando C. Beaman, and John F. Farnsworth, and Stevens) voted against tabling (for impeachment) and six select committee members (Republicans Bignham, Halbert E. Paine, Calvin T. Hulburd and Democrats James B. Beck and James Brooks) voted to table (against impeachment).[26][27]

The next day, pro-impeachment Republican committee members Fernando C. Beaman, George S. Boutwell, John F. Farnsworth, and Thaddeus Stevens met to discuss how to proceed towards impeachment after this setback. However, Stevens concluded that it was a lost cause.[29] This momentarily appeared to mark the death of the prospect of impeaching Johnson[26][28][29] and the end of the revived effort to impeach Johnson.[30]

Select committee approval of an impeachment resolution

[edit]

On February 21, 1868, Johnson disregarded the Tenure of Office Act by moving to dismiss Edwin Stanton as U.S secretary of war and replace him with Lorenzo Thomas as the ad interim secretary of war.[25] That day, Stevens submitted a resolution to the House resolving that the evidence taken on impeachment by the previous (1867) impeachment inquiry run by the Committee on the Judiciary be referred to the House Select Committee on Reconstruction, and that the select committee "have leave to report at any time", which was approved by the House.[8] Also on February 21, a one sentence resolution to impeach Johnson, written by John Covode, was presented to the House. The resolution read, "Resolved, that Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, be impeached of high crimes and misdemeanors."[31][32][33][34] George S. Boutwell motioned that the resolution be referred to the House Select Committee on Reconstruction, and it was.[17][34]

An amended version of Covode's resolution was rapidly drawn up by the Select Committee on Reconstruction.[18] In the morning February 22, 1868, by a party-line vote of 7–2,[35][36] the select committee voted to refer a slightly amended version of Covode's impeachment resolution to the full House.[8][17][37] The amended impeachment resolution read,

"Resolved, That Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, be impeached of high crimes and misdemeanors in office."[37][38]

Remarks made when the full House debated the resolution indicate that the Republican members of the select committee's support for impeachment was motivated by Johnson's attempt to remove Secretary of War Stanton, which they regarded as a violation of the Tenure of Office Act.[8]

| Committee vote on impeachment resolution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| February 22, 1868 | Party | Total votes | ||||

| Democratic | Republican | |||||

| Yea |

0 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Nay | 2 | 0 | 2 | |||

| District | Member | Party | Vote | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michigan 1 | Fernando C. Beaman | Republican | Yea | |

| Kentucky 7 | James B. Beck | Democratic | Nay | |

| Ohio 16 | John Bingham | Republican | Yea | |

| Massachusetts 7 | George S. Boutwell | Republican | Yea | |

| New York 8 | James Brooks | Democratic | Nay | |

| Illinois 2 | John F. Farnsworth | Republican | Yea | |

| Wisconsin 1 | Halbert E. Paine | Republican | Yea | |

| New York 17 | Calvin T. Hulburd | Republican | Yea | |

| Pennsylvania 9 | Thaddeus Stevens | Republican | Yea | |

Majority report of the select committee

[edit]A majority report in support of impeaching Johnson for high crimes and misdemeanors was written and was signed by all of the select committee's Republican members. The dissenting Democratic members did not write a minority view, with James Brooks claiming that he had not had enough time to prepare one.[8]

Full text of the majority report[8]

- That in addition to the papers referred to the committee, the committee find that the President, on the 21st day of February, 1868, signed and issued a commission or letter of authority to one Lorenzo Thomas, directing and authorizing said Thomas to act as Secretary of War ad interim, and to take possession of the books, records, and papers, and other public property in the War Department, of which the following is a copy:

____________EXECUTIVE MANSIONWashington, February 21, 1868.SIR: Hon. Edwin M. Stanton having been this day removed from office as Secretary for the Department of War, you are hereby authorized and empowered to act as Secretary of War ad interim, and will immediately enter upon the discharge of the duties pertaining to that office. Mr. Stanton has been instructed to transfer to you all the records, books, papers, and other public property now in his cusotody and charge.

- Respectfully yours,

- Andrew Johnson

- To Brevet Maj. Lorenzo Thomas

- Adjunct-General of the United States Army, Washington, D.C.

- Official copy respectfully furnished to Hon. Edwin M. Stanton

- L. Thomas,

- Secretary of War ad interim

____________Upon the evidence collected by the committee, which is herewith presented, and in virtue of the powers with which they have been invested by the House, they are of the opinion that Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, be impeached of high crimes and misdemeanors. They therefore recommend to the House the adoption of the accompanying resolution.

Resolved, That Andrew Johnson, President of the United States, be impeached of high crimes and misdemeanors in office.

Subsequent impeachment and trial

[edit]At 3pm on February 22, Stevens presented from the House Select Committee on Reconstruction the impeachment resolution along with the majority report.[8][17][37][39] The impeachment resolution was put to a vote on February 24, 1868, three days after Johnson's dismissal of Stanton. The House of Representatives voted 126–47 (with 17 members not voting) in favor of a resolution to impeach the president for high crimes and misdemeanors,[17][25][40] marking the first time that a president of the United States had been impeached.[25] On February 25, the House (by a vote of 105–36) passed a resolution by George Boutwell that the House Select Committee on Reconstruction be authorized to sit during sessions of the House, ahead of proceedings that included the consideration of impeachment managers and the passage of articles of impeachment.[41][42] Johnson was narrowly acquitted in his Senate trial with a 35 in favor of conviction to 19 votes in favor acquittal, one vote short of the two-thirds majority needed for a conviction.[43]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Building the Case for Impeachment, December 1866 to June 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ a b Benedict, Michael Les (1998). "From Our Archives: A New Look at the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson" (PDF). Political Science Quarterly. 113 (3): 493–511. doi:10.2307/2658078. ISSN 0032-3195. JSTOR 2658078. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Impeachment Efforts Against President Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Stathis, Stephen W.; Huckabee, David C. (September 16, 1998). "Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview" (PDF). sgp.fas.org. Congressional Research Service. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "TO PASS A RESOLUTION TO IMPEACH THE PRESIDENT. (P. 320-2, … -- House Vote #418 -- Jan 7, 1867". GovTrack.us. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Impeachment Rejected, November to December 1867 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "TO PASS THE IMPEACHMENT OF PRESIDENT RESOLUTION. -- House Vote #119 -- Dec 7, 1867". GovTrack.us.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hinds, Asher C. (4 March 1907). "HINDS' PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES INCLUDING REFERENCES TO PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION, THE LAWS, AND DECISIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE" (PDF). United States Congress. pp. 845–847. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ "Journal of the United States House of Representatives (40th Congress, second session) pages 259–262". voteview.com. United States House of Representatives. 1868. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Journal of the United States House of Representatives (40th Congress, second session) pages 259–262". voteview.com. United States House of Representatives. 1868. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d "40th Congress (1867-1869) > Representatives". voteview.com. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Cong. Globe, 40th Cong., 2nd Sess. 1400 (1868)". A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ a b "RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, WITH NOTES AND ANNOTATIONS" (PDF). www.govinfo.gov.

- ^ a b Perros, George P. (1960). "PRELIMINARY INVENTORY OF THE R1OC:ORDS OF THE HOUSE SELECT COMMITTEE ON RECONSTRUCTIO~ 40TH AND 41ST CONGRESSES (1867-1871)". history.house.gov. The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "40th Congress (1867-1869) > Representatives". voteview.com. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "The Capital". Philadelphia Inquirer. February 10, 1868. Retrieved 22 July 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e

This article incorporates public domain material from Stephen W. Stathis and David C. Huckabee. Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

This article incorporates public domain material from Stephen W. Stathis and David C. Huckabee. Congressional Resolutions on Presidential Impeachment: A Historical Overview (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved December 31, 2019.

- ^ a b "U.S. Senate: Impeachment Trial of President Andrew Johnson, 1868". www.senate.gov. United States Senate. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ "The Impeachment Investigation". Newspapers.com. Alexandria Gazette. 10 Feb 1868. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ a b "The Impeachment Question". Bangor Daily Whig and Courier. February 11, 1868 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ White, Ronald C. (2016). American Ulysses: A Life of Ulysses S. Grant. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 454–55. ISBN 978-1-58836-992-5.

- ^ "Impeach of the President". Newspapers.com. The Philadelphia Inquirer. February 10, 1867. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "The Impeachment Investigation - Proceedings on Saturday". Newspapers.com. The Wisconsin State Register. 15 Feb 1868. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ "Letters from Washington". Newspapers.com. The Baltimore Sun. 12 Feb 1868.

- ^ a b c d e "The House Impeaches Andrew Johnson". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian and the Clerk of the House's Office of Art and Archives. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stewart, David O. (2009). Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Licoln's Legacy. Simon and Schuster. pp. 135–137. ISBN 978-1416547495.

- ^ a b c "Washington". Newspapers.com. Chicago Evening Post. February 13, 1868. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Staunton Spectator Tuesday, February 18, 1868". Staunton Spectator. February 18, 1868. Retrieved 22 July 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Domer, Thomas (1976). "The Role of George S. Boutwell in the Impeachment and Trial of Andrew Johnson". The New England Quarterly. 49 (4): 596–617. doi:10.2307/364736. ISSN 0028-4866. JSTOR 364736. Retrieved 11 September 2022.

- ^ Meacham, Jon; Naftali, Timothy; Baker, Peter; Engel, Jeffrey A. (2018). "Ch. 1, Andrew Johnson (by John Meachem)". Impeachment : an American history (2018 Modern Library ed.). New York. p. 52. ISBN 978-1984853783.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Avalon Project : History of the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson - Chapter VI. Impeachment Agreed To By The House". avalon.law.yale.edu. The Avalon Project (Yale Law School Lilian Goldman Law Library). Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "The House Impeaches Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ "Impeachment of Andrew Johnson | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Journal of the United States House of Representatives (40th Congress, Second Session) pages 385". voteview.com. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "By Telegraph". Newspapers.com. The Charleston Daily News. February 24, 1868. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ "Latest New By Telegraph". Newspapers.com. The Daily Evening Express. February 22, 1868. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ a b c "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875". memory.loc.gov. Library of Congress. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "The House adopts a resolution providing for the impeachment of President Andrew Johnson, February 24, 1868" (PDF). www.senate.gov. United States Senate. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ "Impeachment". Newspapers.com. Harrisburg Telegraph. February 22, 1868. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (February 24, 2015). "House votes to impeach Andrew Johnson, February 24, 1868". Politico. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ Hinds, Asher C. (March 4, 1907). HINDS' PRECEDENTS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES OF THE UNITED STATES INCLUDING REFERENCES TO PROVISIONS OF THE CONSTITUTION, THE LAWS, AND DECISIONS OF THE UNITED STATES SENATE (PDF). United States Congress. p. 853. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "The House Impeaches Andrew Johnson". Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian and the Clerk of the House's Office of Art and Archives. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ^ "Impeached but Not Removed, March to May 1868 | US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives". history.house.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 2 March 2021.