Scud missile

| Scud | |

|---|---|

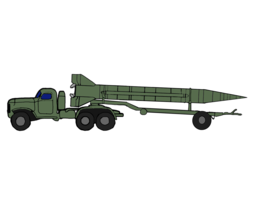

Scud launcher, picture taken at RAF Spadeadam, England | |

| Type | SRBM |

| Place of origin | Soviet Union |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1957–present (Scud A) 1964–present (Scud B) 1965–present (Scud C) 1989–present (Scud D) |

| Used by | see Operators |

| Wars | Yom Kippur War, Iran–Iraq War, Gulf War, Afghan Civil War (1989–1992), Yemeni Civil War (1994), First Chechen War, Second Chechen War, Libyan Civil War, Syrian Civil War, Yemeni Civil War (2014–present), Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen, Second Nagorno-Karabakh War |

| Production history | |

| Designed | From 1950 |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 4,400 kg (9,700 lb) Scud A 5,900 kg (13,000 lb) Scud B 6,400 kg (14,100 lb) Scud C 6,500 kg (14,300 lb) Scud D |

| Length | 11.25 m (36.9 ft) |

| Diameter | 0.88 m (2 ft 11 in) |

| Warhead | Conventional high-explosive, Fragmentation, Chemical VX warhead |

| Engine | Single-stage liquid-fuel |

Operational range | 180 km (110 mi) Scud A 300 km (190 mi) Scud B 600 km (370 mi) Scud C 700 km (430 mi) Scud D |

| Maximum speed | Mach 5 |

Guidance system | Inertial guidance, Scud-D adds DSMAC terminal guidance |

| Accuracy | 3,000 m (9,800 ft) Scud A 450 m (1,480 ft) Scud B 700 m (2,300 ft) Scud C 50 m (160 ft) Scud D |

Launch platform | MAZ-543 Mobile Launcher |

A Scud missile is one of a series of tactical ballistic missiles developed by the Soviet Union during the Cold War. It was exported widely to both Second and Third World countries. The term comes from the NATO reporting name attached to the missile by Western intelligence agencies. The Russian names for the missile are the R-11 (the first version), and the R-17 (later R-300) Elbrus (later developments). The name Scud has been widely used to refer to these missiles and the wide variety of derivative variants developed in other countries based on the Soviet design.

Scud missiles have been used in combat since the 1970s, mostly in wars in the Middle East. They became familiar to the Western public during the 1991 Persian Gulf War, when Iraq fired dozens at Saudi Arabia and Israel. In Russian service it is being replaced by the 9K720 Iskander.

Development

[edit]

The first use of the term Scud was in the NATO name SS-1b Scud-A, applied to the R-11 Zemlya ballistic missile. The earlier R-1 missile had carried the NATO name SS-1 Scunner, but was of a very different design, almost directly a copy of the German V-2 rocket. The R-11 used technology gained from the V-2 as well, but was a new design, smaller and differently shaped than the V-2 and R-1 weapons. The R-11 was developed by the Korolyev OKB[1] and entered service in 1957. The most revolutionary innovation in the R-11 was the engine, designed by A. M. Isaev. Far simpler than the V-2's multi-chamber design, and employing an anti-oscillation baffle to prevent chugging, it was a forerunner to the larger engines used in Soviet launch vehicles.[citation needed]

Further developed variants were the R-17 (later R-300) Elbrus / SS-1c Scud-B in 1961 and the SS-1d Scud-C in 1965, both of which could carry either a conventional high-explosive, a 5- to 80-kiloton thermonuclear, or a chemical (thickened VX) warhead. The SS-1e Scud-D variant developed in the 1980s can deliver a terminally guided warhead capable of greater precision.[citation needed]

All models are 11.35 m (37.2 ft) long (except Scud-A, which is 1 m (3 ft 3 in) shorter) and 0.88 m (2 ft 11 in) in diameter. They are propelled by a single liquid-fuel rocket engine burning kerosene and corrosion-inhibited red fuming nitric acid (IRFNA) with unsymmetrical dimethylhydrazine (UDMH, Russian TG-02 like German Tonka 250) as liquid igniter (self-ignition with IRFNA) in all models.[citation needed]

The missile reaches a maximum speed of Mach 5.[citation needed]

Variants

[edit]Scud-A

[edit]The first of the "Scud" series, designated R-11 (SS-1B Scud-A) originated in a 1951 requirement for a ballistic missile with similar performance to the German V-2 rocket. The R-11 was developed by engineer Viktor Makeev, who was then working in the OKB-1, headed by Sergey Korolev. It first flew on 18 April 1953, was fitted with an Isayev engine using kerosene and nitric acid as propellant. On 13 December 1953, a production order was passed with SKB-385 in Zlatoust, a factory dedicated to producing long-range rockets. In June 1955, Makeev was appointed chief designer of the SKB-385 to oversee the program and, in July, the R-11 was formally accepted into military service.[2] The definitive R-11M, designed to carry a nuclear warhead, was accepted officially into service on 1 April 1958. The launch system was placed on an IS-2 chassis and received the GRAU designation 8K11;[3] only 100 Scud-A launchers were built.[4]

The R-11M had a maximum range of 270 km, but when carrying a nuclear warhead, this was reduced to 150 km.[5] Its purpose was strictly as a mobile nuclear strike vector, giving the Soviet Army the ability to hit European targets from forward areas, armed with a nuclear warhead with an estimated yield of 50 kilotons.[6]

A naval variant, the R-11FM (SS-N-1 Scud-A) was first tested in February 1955, and was first launched from a converted Project 611 (Zulu class) submarine in September of the same year. While the initial design was done by Korolev's OKB-1, the program was transferred to Makeev's SKB-385 in August 1955.[2] It became operational in 1959 and was deployed onboard Project 611 and Project 629 (Golf Class) submarines. During its service, 77 launches were conducted, of which 59 were successful.[7]

Scud-B

[edit]

The successor to the R-11, the R-17 (SS-1C Scud-B), renamed R-300 in the 1970s, was the most prolific of the series, with a production run estimated at 7,000. It served in 32 countries and four countries besides the Soviet Union manufactured copied versions.[6] The first launch was conducted in 1961, and it entered service in 1964.[1]

The R-17 was an improved version of the R-11. It could carry nuclear, chemical, conventional or fragmentation weapons.[6] At first, the Scud-B was carried on a tracked transporter erector launcher (TEL) similar to that of the Scud-A, designated 2P19, but this was not successful and a wheeled replacement was designed by the Titan Central Design Bureau, becoming operational in 1967.[8] The new MAZ-543 vehicle was officially designated 9P117 Uragan. The launch sequence could be conducted autonomously, but was usually directed from a separate command vehicle. The missile is raised to a vertical position by means of hydraulically powered cranes, which usually takes four minutes, while the total sequence lasts about one hour.[6]

Scud-C

[edit]The Makeyev OKB also worked on an extended-range version of the R-17, known in the West as SS-1d Scud-C, that was first launched from Kapustin Yar in 1965. Its range was brought up to 500–600 km, but at the cost of a greatly reduced accuracy and warhead size. Eventually, the advent of more modern types in the same category, such as the TR-1 Temp (SS-12 Scaleboard), made the Scud-C redundant, and it apparently did not enter service with the Soviet armed forces.[9]

Scud-D

[edit]The R-17 VTO (SS-1e Scud-D) project was an attempt to enhance the accuracy of the R-17. The Central Scientific Research Institute for Automation and Hydraulics (TsNIAAG) began work on the project in 1967, using an optical guidance system where a photograph of the target (provided through air reconnaissance) was inserted into a holder. This method was impractical, as the system was only effective in clear weather and it was difficult to take the proper photographs under field conditions. The Soviet artillery troops were not favorable towards the concept due to those limitations.[10]

In 1974, the VTO programme was revisited to take advantage of miniaturized computer hardware, where the guidance system would rely on a digitized image (DSMAC). This also made it possible to reassign targets from the missile warhead's computer library. The warhead was tested on an Su-17 in 1975 and the first test launch was conducted on 29 September 1979, where the missile hit within a few meters of the target. Development continued through the 1980s, and the design was modified to have a separating warhead and to have it make terminal corrections before impact. The first two test launches of this version in 1984 failed; the optical lens' inner surface on the missile's nose suffered from dust buildup and this was corrected after redesign work.[10]

The system was accepted into initial service as the 9K720 Aerofon in 1989.[11] However, by this time, more advanced weapons were in use, such as the OTR-21 Tochka (SS-21) and the R-400 Oka (SS-23), and the Scud-D was not acquired by the Soviet Armed Forces. Instead it was proposed for export as an upgrade for Scud-B users, in the 1990s.[11]

Unlike previous Scud versions, the 9K720 had a warhead that separated from the missile's body, and was fitted with its own terminal guidance system. With a TV camera fitted in the nose, the system could compare the target area with data from an onboard computer library (DSMAC).[11] In this way, it was thought to attain a circular error probable (CEP) of 50 m.

Characteristics

[edit]| NATO codename | Scud-A | Scud-B | Scud-C | Scud-D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. DIA | SS-1b | SS-1c | SS-1d | SS-1e |

| Official designation | R-11 | R-17/R-300 | ||

| Deployment Date | 1957 | 1964 | 1965 | 1989 |

| Length | 10.7 m | 11.25 m | 11.25 m | 12.29 m |

| Width | 0.88 m | 0.88 m | 0.88 m | 0.88 m |

| Launch weight | 4,400 kg | 5,900 kg | 6,400 kg | 6,500 kg |

| Range | 180 km | 300 km | 600 km | 700 km |

| Payload | 950 kg | 985 kg | 600 kg | 985 kg |

| Accuracy (CEP) | 3,000 m | 450 m | 700 m | 50 m |

Al Hussein and Iraqi variants

[edit]Hwasong-5/Shahab-1

[edit]North Korea obtained its first Scud-Bs from Egypt in 1979 or 1980.[12] These missiles were reverse engineered, and reproduced using North Korean infrastructure, including the 125 factory at Pyongyang, a research and development institute at Sanum-dong and the Musudan-ri Launch Facility.[13] The first prototypes were completed in 1984, and designated Hwasong-5. They were exact replicas of the R-17Es obtained from Egypt. The first test flights occurred in April 1984, but the first version saw only limited production, and no operational deployment, as its purpose was only to validate the production process.[citation needed]

Production of the definitive version began at a slow rate in 1985. The type incorporated several minor improvements over the original Soviet design. The range was increased by 10 to 15 percent and it could carry High Explosive (HE) or cluster chemical warheads. Throughout the production cycle, until it was phased out in favour of the Hwasong-6 in 1989, the DPRK manufacturers are thought to have carried out small enhancements, in particular to the guidance system.[13]

In 1985, Iran acquired 90 to 100 Hwasong-5 missiles from North Korea. A production line was also established in Iran, where the Hwasong-5 was produced as the Shahab-1.[13]

Hwasong-6/Shahab-2

[edit]The Hwasong-6 was first test-flown in June 1990, and entered full-scale production the same year, or in 1991, until it was superseded by the Rodong-1. It features an improved guidance system, a range of 500 km, but had its payload reduced to 770 kg, though the dimensions are identical to the original Scud. Due to difficulties in procuring MAZ-543 TELs, the North Koreans had to produce a local copy. By 1999, North Korea was estimated to have produced 600 to 1,000 Hwasong-6 missiles, of which 25 served for testing, 300 to 500 were exported, and 300 to 600 are used by the Korean People's Army.[14]

The Hwasong-6 was exported to Iran where it is known as the Shahab-2, and to Syria, where it is manufactured under license with Chinese assistance.[14] Also, according to SIPRI, 150 Scud-C were exported to Syria in 1991–96, 5 to Libya in 1999, 45 to Yemen in 2001–02.[15]

Hwasong-7/Shahab-3

[edit]The Nodong (also referred as RoDong, Hwasong-7), was the first North Korean missile to feature important modifications from the Scud design.[16] Development began in 1988, and the first missile was launched in 1990, but it apparently exploded on its launch pad. A second test was carried out in May 1993 successfully.[12][14]

The main characteristics of the Rodong are a range of 1000 km and a CEP estimated at 2,000–4,000 m, giving the North Koreans the ability to strike Japan.[17] The missile is substantially larger than the Hwasong series, and its Isayev 9D21 engine was upgraded with help from Makeyev OKB. Some assistance came also from China and Ukraine while a new TEL was designed using an Italian Iveco truck chassis and an Austrian crane. The rapidity with which the Rodong was designed and exported after just two tests came as a surprise for many Western observers, and led to some speculation that it was in fact based on a cancelled Soviet project from the Cold War period, but this has not been proven.[18]

Iran is known to have financed much of the Rodong program, and in return is allowed to produce the missile, as the Shahab-3. While the first prototypes may have been acquired as early as 1992, production began only in 2001, with assistance from Russia.[citation needed] The Rodong has also been exported to Egypt and Libya.

Hwasong-9/Scud-ER

[edit]The Hwasong-9,[19][20] also called as Scud-ER (Scud Extended Range), is essentially a North Korean modification of the Hwasong-6 that can exchange payload for greater range.

Hwasong-9 demonstrated range of 1,000 km (620 mi) with 500 kg payload.[21][22]

Qiam 1

[edit]Iran began development of the indigenous Qiam missile prior to 2010, when it was first publicly tested.[23] It is developed from the Shahab-2/Hwasong-6.[24]

The Qiam 1 has a range of 750 km (470 mi) and 10 m (33 ft) (CEP) accuracy.[24] The most noticeable difference from the Shahab-2 is a lack of fins—which could be used to reduce the missile's radar signature during ascent as fins reflect radar.[25] Removing fins from a missile also reduces the structural mass, so the payload weight or missile range can be increased.[25][24] Without the fins and associated drag, the missile can be more responsive to changes in trajectory.[25] Iranian sources cite an improved guidance system on the missile, and analysts note that adjusting the missile's in-flight trajectory without fins requires a highly responsive guidance system.[23][24] The Qiam 1's accuracy is also improved with the addition of a separable warhead.[25] Other changes to the warhead include a "baby-bottle" shape, possibly to increase drag and thus stability during reentry at the expense of range, potentially increasing accuracy. The shape can also increase the terminal velocity of the warhead, making it harder to intercept.[26][24][27]

Deliveries began in either 2010 or 2011.[28][29] The missile's first combat use was against ISIS militants on 18 June 2017.[30] The Burkan 2-H used by the Houthis in Yemen is potentially related, or the Qiam 1 has potentially been used by that group.[31][32]

Burkan-1

[edit]The Houthi forces in Yemen unveiled the Burkan-1[33] (also spelled as Borkan 1 and Burqan 1[34]) on 2 September 2016 when it was fired toward King Fahd International Airport.[35][36]

The missile's range is 800 kilometres (500 mi), greater than the Soviet-made Scud-B missiles the Houthi forces took control of in 2015.[36][37] Missiles shot down mid-flight in October 2016 and July 2017 were claimed to target the holy city of Mecca by Saudi Arabia, while the Houthis claimed the targets were airports in the region.[38][39]

Burkan 2-H

[edit]The Houthi forces in Yemen unveiled the Burkan 2-H[40] (also spelled as Borkan H2 and Burqan 2H[34]) when it was launched at Saudi Arabia on 22 July 2017.[41]

Analysts identify it as based on the Iranian Qiam 1/Scud-C,[42][32] Iranian Shahab-2/Scud-C,[42] or Scud-D[33] missile. Pictures indicate a "baby bottle" re-entry vehicle, like the Shahab-3 and Qiam 1 missiles. The missile's exact range is unknown, but is greater than 800 kilometres (500 mi).[43]

It has been launched in July 2017, and a second launch was claimed on 4 November 2017, with the missile shot down over the Saudi Arabian capital, Riyadh.[34] According to the US State Department, the missile was actually an Iranian Qiam 1.[31] Saudi Arabia's Ministry of Culture and Information also supplied the Associated Press with pictures from a military briefing of what it claimed were components from the intercepted missile bearing Iranian markings matching those on other pictures of the Qiam 1.[32]

Golan-1 and Golan-2

[edit]The Golan missiles are Syrian modernization and licensed production of Scud missiles (versions B, C and D).[44]

The Golan-1 missile is simply a licensed copy of the Scud-C missile without major changes. The Golan-2 missile is a modernization of the Scud-D, with an increased range of up to 850 km (compared to 700 km for the basic version).[44] Syrian engineers have also converted various versions of Scud missiles (possibly including Golan missiles) to use cluster munitions.[44] Developed and produced in Syria by Syrian Scientific Studies and Research Center.[44] The number of missiles produced is unknown. Used in the Syrian Civil War.

Operational use

[edit]

The Scud missile family is one of the few ballistic missiles to be extensively used in actual warfare by different forces, second only to the V-2 in terms of combat launches.The first recorded combat use of the Scud was at the end of the Yom Kippur War in 1973, when three missiles were fired by Egypt against Israeli-held Arish and bridgehead on the western bank of the Suez canal.[45] Seven Israeli soldiers were killed.[46] Libya responded to U.S. airstrikes in 1986 by firing two Scud missiles at a U.S. Coast Guard navigation station on the nearby Italian island of Lampedusa, which missed their target. Scud missiles were used in several regional conflicts that included use by Soviet and Afghan Communist forces in Afghanistan, and Iranians and Iraqis against one another in the so-called "War of the cities" during the Iran–Iraq War. Scuds were used by Iraq during the Gulf War against Israel and coalition targets in Saudi Arabia.[47]

More than a dozen Scuds were fired from Afghanistan at targets in Pakistan in 1988, and against targets within Afghanistan in March 1991. There were also a small number of Scud missiles used in the 1994 civil war in Yemen, as well as by Russian forces in Chechnya in 1996 and onwards. The missiles saw some minor use by forces loyal to Muammar Gaddafi in the Libyan Civil War. They have reportedly been used recently in the ongoing Syrian civil war by the Syrian Army.[48]

Iran–Iraq War

[edit]Iraq was the first to use ballistic missiles during the Iran–Iraq War, firing limited numbers of Frog-7 rockets at the towns of Dezful and Ahvaz. On 27 October 1982, Iraq launched its first Scud-Bs at Dezful killing 21 civilians and wounding 100. Scud strikes continued during the following years, intensifying sharply in 1985, with more than 100 missiles falling inside Iran.[49]

In response, the Iranians searched for a source of ballistic weapons, finally meeting success in 1985, when they obtained a small number of Scud-Bs from Libya and Syria: in addition to supplying these missiles, Syria also taught Iran the technology to produce them. These weapons were assigned to a special unit, the Khatam Al-Anbya force, attached to the Pasdaran. On 12 March, the first Iranian Scuds fell in Baghdad and Kirkuk. The strikes infuriated Saddam Hussein, but the Iraqi response was limited by the range of their Scuds, that could not reach Tehran. After a request for TR-1 Temp (SS-12 Scaleboard) missiles was refused by the Soviets, Iraq turned to developing its own long-range version of the Scud missile, that became known as the Al Hussein. In the meantime, both sides quickly ran out of missiles, and had to contact their international partners for resupply. In 1986, Iraq ordered 300 Scud-Bs from the Soviet Union, while Iran turned to North Korea for missile deliveries and for assistance in developing a domestic missile industry.[citation needed]

By 1988 the fighting along the border had reached a stalemate, and both belligerents began employing terror tactics in order to break the deadlock. Lasting from 29 February to 20 April, this conflict became known as the war of the cities and saw an intensive use of Scud missiles in what became known as the "Scud duel". The first rounds were fired by Iraq, when seven Al-Husseins landed in Tehran on 29 February. In all, Iraq fired 189 missiles, mostly of the Al-Hussein type, of which 135 landed in Tehran, 23 in Qom, 22 in Isfahan, four in Tabriz, three in Shiraz and two in Karaj.[49] During this episode, Iraq's missiles killed 2,000 Iranians, injured 6,000, and caused a quarter of Tehran's population of ten million to flee the city.[50] The Iranian response included launching 75 to 77 Hwasong-5s, a North Korean Scud variant, at targets in Iraq, mostly in Baghdad.[49]

Prior to the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the government of Saddam Hussein had asserted that Iran fired dozens of Scud missiles at the People's Mujahedin (MKO) in Iraq in 1999 and 2001, with the MKO itself claiming that Iran fired more missiles at Iraq in 2001 than it did during the entire Iran–Iraq War.[51][52][53]

Civil war in Afghanistan

[edit]The most intensive – and less well-known – use of Scud missiles occurred during the civil war in Afghanistan between 1989 and 1992. As compensation for the withdrawal of Soviet troops in 1989, the USSR agreed to deliver sophisticated weapons to the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (DRA), among which were large quantities of Scud-Bs, and possibly some Scud-Cs as well.[6] The first 500 were transferred during the early months of 1989, and soon proved to be a critical strategic asset for the DRA. Every Scud battery was composed of three TELs, three reloading vehicles, a mobile meteorological unit, one tanker and several command and control trucks.[54] During the mujahideen attack against Jalalabad, between March and June 1989, three firing batteries manned by Afghan crews advised by Soviets fired approximately 438 missiles in defense of the embattled garrison.[55] Soon all the heavily contested areas of Afghanistan, such as the Salang Pass and the city of Kandahar, were under attack by Scud missiles.[citation needed] Due to its imprecision, the Scud was used as an area bombing weapon, and its effect was psychological as well as physical: the missiles would explode without warning, as they travelled faster than the sound they produced in-flight. At the time, reports indicated that Scud attacks had devastating consequences on the morale of the Afghan rebels, who eventually learned that by applying guerilla tactics, and keeping their forces dispersed and hidden, they could minimize casualties from Scud attacks.[49] The Scud was also used as a punitive weapon, striking areas that were held by the resistance. In March 1991, shortly after the town of Khost was captured, it was hit by a Scud attack. On 20 April 1991, the marketplace of Asadabad was hit by two Scuds, which killed 300 and wounded 500 inhabitants. Though the exact toll is unknown, these attacks resulted in heavy civilian casualties.[56] The explosions destroyed the headquarters of Islamic leader Jamil al-Rahman, and killed a number of his followers.[57] In all, between October 1988 and February 1992, with 1,700 to 2,000 Scud launches,[49] Afghanistan saw the greatest concentration of ballistic weapons fired since World War II.[58] After January 1992, the Soviet advisors were withdrawn, reducing the Afghan army's ability to use their ballistic missiles. On 24 April 1992, the mujahideen forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud captured the main Scud stockpile at Afshur but members of the 99th Missile Brigade had ditched their uniforms leaving Massoud's men with no way of operating such weapons. As the communist government collapsed, the few remaining Scuds and their TELs were divided among the rival factions fighting for power. Due to the lack of knowledge on such weapons, between April 1992 and 1996, only 44 Scuds were fired in Afghanistan. When the Taliban arrived in power in 1996, they captured a few of the remaining Scuds, but lack of maintenance had reduced the state of the missile force to such an extent that there were only five Scud firings, until 2001. After the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, the last four surviving Scud launchers were destroyed in 2005.[59]

Gulf War

[edit]Scud attacks

[edit]

At the outbreak of the Gulf War, Iraq had an effective, if limited, ballistic missile force. Besides the original Scud-B, several local variants had been developed. These included the Al-Hussein, developed during the Iran–Iraq War, the Al-Hijarah, a shortened Al-Hussein, and the Al-Abbas, an extended-range Scud fired from fixed launching sites, that was never used. The Soviet-built MAZ-543 vehicle was the prime launcher, along with a few locally designed TELs, the Al Nida and the Al Waleed.[citation needed]

Scuds were responsible for most of the coalition deaths outside Iraq and Kuwait. Of a total 88 Scud missiles, 46 were fired into Saudi Arabia and 42 into Israel.[60][61] Twenty-eight members of the Pennsylvania National Guard were killed when a Scud struck a United States Army barracks in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.[62]

Scud hunting

[edit]

The United States Air Force organized air patrols over areas where Scud launchers were suspected to operate, namely western Iraq near the Jordanian border, where the Scuds were fired at Israel, and southern Iraq, where they were aimed at Saudi Arabia. A-10 strike aircraft flew over these zones during the day, and F-15Es fitted with LANTIRN pods and synthetic aperture radars patrolled at night. However, the infrared signatures and radar signatures of the Iraqi TELSs were almost impossible to distinguish from ordinary trucks and from the surrounding electromagnetic clutter. During the war, while patrolling, strike aircraft managed to sight mobile TELs on 42 occasions, but only eight times the aircraft were able to locate the targets well enough to release their ordnance.[63] In addition, the Iraqi missile units dispersed their Scud TELs and hid them in culverts, wadis, or under highway bridges. They also practiced "shoot-and-scoot" tactics, withdrawing the launcher to a hidden location immediately after it had fired, while the launch sequence that usually took 90 minutes was reduced to half an hour. This enabled them to preserve their forces, despite optimistic claims by the coalition. A post-war Pentagon study concluded that relatively few launchers had been destroyed by coalition aircraft.[63]

Ground-based special forces from the United Kingdom were covertly inserted into Iraq to locate and destroy Scud launchers, either by directing airstrikes or in some cases attacking them directly with MILAN man-portable missiles. An example was the 8-man SAS patrol designated Bravo Two Zero, led by "Andy McNab" (a pseudonym). This patrol resulted in the death or capture of all but one of its members, "Chris Ryan".[63]

The mobility of Scud TELs allowed for a choice of firing position and increased the survivability of the weapon system to such an extent that, of the approximately 100 launchers claimed destroyed by coalition pilots and special forces in the Gulf War, not a single destruction could be confirmed afterwards. After the war, UNSCOM investigations showed that Iraq still had 12 MAZ-543 vehicles, as well as seven Al-Waleed and Al-Nidal launchers, and 62 complete Al-Hussein missiles.[63]

1994 Yemen civil war

[edit]During the 1994 civil war in Yemen, South Yemen separatists fired Scud missiles at the Yemeni capital of Sana'a.[64]

Chechen Wars

[edit]A small number of Scuds were used by Russian forces in 1996 during the First Chechen War and in late 1999/early 2000 during the Second Chechen War, including during the Battle of Grozny (1999–2000).[65][66] Although frequently reported by media as Scuds, the majority of the 60–100 SRBMs fired in the Chechen Wars were the OTR-21 Tochka (SS-21 Scarab-B).[66]

Libyan Civil War

[edit]In May 2011, early during the Libyan Civil War, it was rumored that Scud-B's had been fired by Muammar Gaddafi's forces against anti-Gaddafi forces.[67] The first confirmed use happened several months later, when on 15 August 2011, as anti-Gaddafi forces encircled the Gaddafi-controlled capital of Tripoli, Libyan Army forces near Gaddafi's hometown of Sirte fired a Scud missile toward anti-Gaddafi positions in Cyrenaica, well over 100 kilometers away. The missile struck the desert near Ajdabiya, causing no casualties.[68] On 22 August 2011, a second Scud-B also fired by Gaddafi forces in Sirte. On 23 August, opposition forces in Misrata reported that four Scud-B missiles were fired against the city from Sirte, but had caused no damage. Initial claims that an Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System-equipped US Navy cruiser shot down the missiles over the Gulf of Sidra[69] were later denied by US DoD officials.[70]

Syrian Civil War

[edit]On 12 December 2012, it was reported by various outlets that the Syrian Army has begun using short-range ballistic missiles against rebels in the Syrian civil war. According to NATO officials, "allied intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance assets" had detected the launch of a number (later reports said at least 6) of unguided, short-range ballistic missiles inside Syria. The trajectory and distance travelled indicated that they were Scud-type missiles, although no information on the type of Scud being used was provided at the time. An American intelligence official, who asked not to be identified, confirmed that missiles had been fired from the Damascus area at targets in northern Syria, where the majority of the rebels' bases and facilities are located.[71][72]

Three districts in the rebel-held eastern part of Aleppo and the nearby city of Tel Rifat were hit by ballistic missiles on 22 February 2013, flattening up to 20 houses in each of the places hit. Human Rights Watch inspector Ole Solvang toured the areas targeted by Scuds on 25 February, saying that he "has never seen such destruction" during his past visits to the country. According to the New York-based organization at least 141 people were killed in the attacks, including 71 children. The statement added that there was no sign of rebel presence in the areas hit, meaning that the attacks were unlawful. Syrian Information Minister Omran al-Zoabi denied the government was using ballistic weapons, even as opposition activists claimed more than 30 had been launched since December 2012.[73][74]

Yemeni Civil War (2015–present)

[edit]Houthis possessed 300 Scud missiles as of June 2015, although Saudi-led air strikes allegedly damaged or destroyed "most of them."[75] Between 2015 and November 2017, Houthi forces fired more than 170 ballistic missiles at Saudi Arabia, including Scud, Scarab, and modified SA-2 missiles.[76][77] As of October 2016, there were 85 confirmed interceptions using Patriot missiles.[77] In addition to Scud-B missiles, there is a report of a single Scud-C missile launched on 6 June 2015 at Al-Salil Military Base.[78][79] Local versions of Scud missiles, known as the Burkan 1 and Burkan 2-H, have also been displayed and used by the Houthis beginning in September 2016.[42][35]

Nagorno-Karabakh war (2020)

[edit]On 11 October 2020 a Scud missile was fired from the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh at Ganja, Azerbaijan, the country's second largest city. As a result, according to Azerbaijan official sources, 10 people, including four women, were killed and 35 people, including children, were injured.[80][81][82][83]

On 16 October 2020, Armenian Armed Forces in Nagorno-Karabakh fired another Scud missile at Ganja. Officials in Azerbaijan announced that at least 13 people, including two infants, had been killed, with more than 50 others injured.[84][85][86][87][88][89]

Azerbaijan destroyed at least one Scud missile launcher during the course of the war.[90]

Operators

[edit]

Operators of Scuds or Scud derivatives as of 2022 are:[6]

Current operators

[edit] Algeria

Algeria- (Scud-B, Scud-D): Some sources said that Algeria has received Scud B and D

Armenia

Armenia- (Scud-D): 8 launchers, 32 missiles[91][92]

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Democratic Republic of the Congo- (Scud-B)[93]

Egypt

Egypt- (Scud-B, Hwasong-6, Project T)

Iran

Iran- (Scud-B, Hwasong-5, Shahab-1, Shahab-2, Shahab-3, Rodong-1, Qiam 1)

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan- (Scud-B)

Libya

Libya- (Scud-B)

Myanmar

Myanmar- (Hwasong-6, Hwasong-5[94][95])

North Korea

North Korea- (Scud-E, Scud-B, Scud-C, Hwasong-5, Hwasong-6, Rodong-1)[a]

Oman

Oman- (Scud-B)

Syria

Syria- (Scud-B, Scud-C, Golan-1, Golan-2, Scud-D, Scud-ER, Shahab-1, Shahab-2, Hwasong-5, Hwasong-6, Rodong-1)[96]

United States

United States- c. 30 Scud-B missiles and four TELs acquired in 1995, and converted into targets by Lockheed Martin.[6]

Vietnam

Vietnam- (Scud-B, Scud-C, Hwasong-5, Hwasong-6)

Yemen

Yemen- (Scud-B, Scud-C, Volcano 1, Volcano H-2)

Former operators

[edit] Afghanistan

Afghanistan- (Scud-B)[97] – 30 launchers and 2,300 missiles delivered to the DRA between 1988 and 1991.[98] After the US invasion of Afghanistan, the last 4 remaining launchers were scrapped in 2005[59]

Belarus

Belarus- 60 launchers, retired in May 2005

Bulgaria

Bulgaria- (Scud-B) – 36 launchers, retired[99]

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia- (Scud-B) – 30 launchers

Czech Republic

Czech Republic- (Scud-B) – 27 launchers, retired

East Germany

East Germany- (Scud-A, Scud-B) – 24 launchers plus decoys,[100] retired 1990

Hungary

Hungary- (Scud-B) – 9 launchers, retired, destroyed in 1995[101]

Iraq

Iraq- (Scud-B, Al-Hussein, Al-Abbas) – 24–36 launchers[102] plus decoys,[100] 819 missiles,[102] plus 11 MAZ-543 launchers for Al-Hussein.

Poland

Poland- (Scud-B) – 30 launchers, retired in 1989

Pakistan

Pakistan- (Scud-B) - unknown number of Scuds were acquired from former Afghan National Army in 1980s as part of foreign technology assessments, none were deployed in the military service.: 236 [103]

Romania

Romania- (Scud-B) – 18 launchers, retired

Russia

Russia- (Scud-C, Scud-D) – ~300 launchers remaining at the dissolution of the Soviet Union, retired

South Yemen

South Yemen- 6 launchers and an unknown quantity of R-17E missiles bought in 1979[104]

Soviet Union

Soviet Union- ~660 launchers

Slovakia

Slovakia- (Scud-B)-retired

United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates- 25 Hwasong-5s purchased from North Korea in 1989. The UAE military were not satisfied with the quality of the missiles, and they were kept in storage.[13]

Ukraine

Ukraine- 50 launchers and 185 missiles, all destroyed[105]

See also

[edit]- List of missiles

- Shahab-1 – An Iranian copy of the Scud-B

- 9K720 Iskander – Russian Scud replacement

Notes

[edit]- ^ The H-5, H-6 and R1 are derivatives of the Scud

References

[edit]- ^ a b Wade, Mark. "R-17". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 19 February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- ^ a b Wade, Mark. "R-11". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 5 February 2008. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ Zaloga, p.7

- ^ Elbrus (SS-1C Scud-B)[usurped]. Military-Today.

- ^ Zaloga, p.4

- ^ a b c d e f g "SS-1 'Scud' (R-11/8K11, R-11FM (SS-N-1B) and R-17/8K14)". Jane's Information Group. 26 April 2001. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ "R-11FM / SS-1b Scud". Federation of American Scientists. 13 July 2000. Archived from the original on 12 August 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2008.

- ^ Zaloga, pp.14–15

- ^ Zaloga, p.17

- ^ a b Zaloga, Steven J.; Markov, David R.; Hull, Andrew W. (1999). Soviet/Russian Armor and Artillery Design Practices: 1945 to Present. Darlington, Maryland: Darlington Productions. p. 383. ISBN 1892848015.

- ^ a b c Zaloga, p.19

- ^ a b "Egypt's Missile Efforts Succeed with Help from North Korea". Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control. 1 September 1996. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ a b c d Bermudez, Joseph S. (1999). "A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK: First Ballistic Missiles, 1979–1989". James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Archived from the original on 11 November 2001. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ a b c Bermudez, Joseph S. (1999). "A History of Ballistic Missile Development in the DPRK: Longer Range Designs, 1989–Present". James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. Archived from the original on 11 November 2001. Retrieved 14 February 2008.

- ^ Yomiuri Shimbun (in Japanese) 2009-03-27, ver.13, page11

- ^ Cordesman, Anthony H.; Hess, Ashley (10 July 2013). The Evolving Military Balance in the Korean Peninsula and Northeast Asia: Missile, DPRK and ROK Nuclear Forces, and External Nuclear Forces. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-1-4422-2520-6. Retrieved 30 August 2023.

- ^ "CNS Special Report on North Korean Ballistic Missile Capabilities". James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies. 22 March 2006. Archived from the original on 11 November 2001. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ "Nodong: Overview and Technical Assessment". Nuclear Threat Initiative. May 2003. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2008.

- ^ "Real Name! — NEAMS". Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "Hwasong-9 (Scud-ER)". Missile Threat Project. 23 April 2024. Retrieved 11 September 2024.

- ^ "U.S. Expert claims latest N.K. Missile launches Scud-ER". 9 September 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ "North Korea Launches Four Missiles "Simultaneously"". 6 March 2017. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Iran Test-Fires New Surface-to-Surface Missile". Fars News Agency. 25 August 2010. Archived from the original on 25 August 2010. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d e "Qiam 1". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d Wright, David (25 August 2010). "Iranian Qiam-1 Missile Test". Union of Concerned Scientists: [Blog] All Things Nuclear. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ Rubin, Uzi (24 August 2008). "Iran's New "Baby Bottle" Shihab". Middle East Missile Monitor. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Eisenstadt, Michael (November 2016). "Research Notes" (PDF). The Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "The Launch of a Massive Rocket "Uprising 1" by the Air Force Corps [آغاز تحویل انبوه موشک قیام 1 به نیروی هوافضای سپاه]". IRIB News. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011.

- ^ Hildreth, Steven (6 December 2012). "Iran's Ballistic Missile and Space Launch Programs" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- ^ "US Air Force official: Missile targeting Saudis was Iranian". Ledger-Enquirer. 10 November 2017. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Press Release: Ambassador Haley on Weapons of Iranian Origin Used in Attack on Saudi Arabia". United States Mission to the United Nations. 7 November 2017. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Gambrell, Jon (11 November 2017). "Q&A: US, Saudi Arabia accuse Iran over Yemen missile launch". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b Lewis, Jeffrey (27 October 2016). "Yemen's Burkan-1 Missile". Arms Control Wonk. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Lister, T; Albadran, A; Al-Masmari, H; Sirgany, SE; Levenson, E (4 November 2017). "Saudi Arabia intercepts ballistic missile over capital". CNN. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ a b Yemenis unveil 'new' Burkan-1 ballistic missile. Binnie, Jeremy. 7 September 2016. IHS Jane's Defence Weekly. http://www.janes.com/article/63468/yemenis-unveil-new-burkan-1-ballistic-missile. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20170731043623/http://www.janes.com/article/63468/yemenis-unveil-new-burkan-1-ballistic-missile. Accessed 6 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Missile Force Launches New Missile on Saudi Territory". Almotamar.net. 2 September 2016. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Carlino, Ludovico (26 July 2017). "Incremental improvements in Houthi militants' ballistic missile campaign increase risk to assets in central Saudi Arabia". Jane's IHS. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "Yemen's Houthis launch missile toward Saudi holy city, coalition says". Reuters. 27 October 2016. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "Saudi coalition downs Yemeni rebel missile near Mecca". France24. 31 July 2017. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Edroos, F (5 November 2017). "Yemen's Houthis fire ballistic missile at Riyadh". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 5 November 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ "Yemen targets Saudi oil refinery with ballistic missile". Yemen Press. 23 July 2017. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 6 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Brügge, Norbert (10 November 2017). "The Soviet "Scud" Missile Family". Archived from the original on 11 November 2017. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "Saudis accuse Iran of 'direct aggression' over Yemen missile". BBC. 7 November 2017. Archived from the original on 10 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b c d "الترسانة الصاروخية السورية: من مفاجئات أي حرب مقبلة..."

- ^ "SS-1C 'Scud B'". MissileThreat.csis.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ^ "החטיבה במלחמה". Archived from the original on 3 May 2007. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- ^ "The day Israel's wars changed forever". The Jerusalem Post | Jpost.com. 17 January 2021.

- ^ ERIC SCHMITT; MICHAEL R. GORDON (13 December 2012). "U.S. to Send 2 Missiles Batteries to Turkey to Deter Syria". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Perrimond, Guy (2002). "1944–2001: The threat of theatre ballistic missiles" (PDF). TTU Online. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- ^ "Iraq's Scud Ballistic Missiles: Historical back ground". GulfLink.osd.mil. 25 July 2000. Archived from the original on 29 February 2008. Retrieved 25 February 2008.

- ^ "Iraq says Iran fired Scuds". BBC News. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "Iraq Accuses Iran of Scud Missile Attack". Los Angeles Times. 19 April 2001. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "Iran". Worldtribune.com. 25 April 2001. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ Yousaf & Adkin, p. 230

- ^ Zaloga, p. 39

- ^ Lewis, George, Fetter, Steve and Gronlund, Lisbeth (1993). Casualties and damage from Scud attacks in the 1991 Gulf War. Defense and Arms Control Studies Program, Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, p. 13

- ^ Adamec, Ludwig (2011). Historical Dictionary of Afghanistan. Scarecrow Press, p. 226. ISBN 0810878151

- ^ Marshall, A.(2006); Phased Withdrawal, Conflict Resolution and State Reconstruction; Conflict research Studies Centre; ISBN 1-905058-74-8 [1] Archived 1 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Zaloga, p.39

- ^ "Iraq: The Great Scud Hunt". Time. 23 December 2002. Archived from the original on 22 October 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- ^ Rostker, Bernard (2000). "Information Paper: Iraq's Scud Ballistic Missiles". Wisconsin Project on Nuclear Arms Control from 2000–2006. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2009.

- ^ Schmitt, Eric (20 May 1991). "After the war; Army Is Blaming Patriot's Computer For Failure to Stop the Dhahran Scud". The New York Times. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d Rosenau, William (2001). Coalition Scud-hunting in Iraq, 1991 (PDF). RAND corporation. ISBN 0-8330-3071-X. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2013. Retrieved 8 November 2012.

- ^ "Five Scuds fired at Yemeni capital as war worsens: The Guardian, 7 Apr 94". 6 May 2009. Archived from the original on 6 May 2009. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ J. B. A. Bailey (2004). Field artillery and firepower. Naval Institute Press. p. 422. ISBN 1591140293.

- ^ a b Olga Oliker (2001). Russia's Chechen Wars 1994–2000: Lessons from Urban Combat. Rand Corporation. p. 82. ISBN 0833032488.

- ^ Gilligan, Andrew (8 May 2011). "The forgotten frontline in Libya's civil war". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ "Col Gaddafi fires scud missile at rebel territory as Nato braces itself for final violent showdown". The Daily Telegraph. 15 August 2011. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2011.

- ^ Stephen, Christopher (24 August 2011). "Libyan rebels advance on Gaddafi's home town". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ "DoD denies reports Navy shot down Libyan Scuds". DoD Buzz. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ^ "Syrian Forces Have Fired Scud Missiles at Insurgents, U.S. Says". The New York Times. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ "Scud-type missiles launched in Syria -NATO official". Trust.org. 12 December 2012. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ "Syrian ballistic missiles killed 141 civilians last week-HRW". Trust.org via Reuters. 26 February 2013. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ "Scud Missile Attack Reported in Aleppo". The New York Times. 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ^ Al-Shihri, Abdullah (6 June 2015). "Saudi Arabia shoots down Scud missile fired from Yemen". Defense News. Retrieved 10 November 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Winter, Chase (11 November 2017). "US Air Force: Missiles fired at Saudi Arabia from Yemen have 'Iranian markings'". DW. Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Interactive: The Missile War in Yemen". Center for Strategic and International Studies. 13 October 2016. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ Ramsey, Syed (2016). Tools of War: History of Weapons in Modern Times. PublishDrive. ISBN 9789386834157. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ^ "Saudi troops intercept Scud fired from Yemen". Arab News. 6 June 2015. Archived from the original on 5 August 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "Hours after truce agreed, children became orphans in Azerbaijan". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "Armenia Azerbaijan: Reports of fresh shelling dent ceasefire hopes". BBC News. 12 October 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "Azerbaijan claims Armenia shelled city of Ganja, in conflict that could spill over into direct war". www.abc.net.au. 4 October 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "Azerbaijan says Armenian forces shell second city of Ganja". Insider. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ BBC news (17 October 2020). "Nagorno-Karabakh: Civilians hit amid Armenia Azerbaijan conflict". BBC News.

- ^ "Azerbaijan: Armenian missile killed 13, wounded over 50". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "At least 12 killed in missile attack on Azerbaijan's 2nd biggest city: Baku". La Prensa Latina Media. 17 October 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ News, Mirage (17 October 2020). "Azerbaijan says 13 killed in new Scud missile strike by Armenia | Mirage News". www.miragenews.com. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ r/KarabakhConflict - Russian-made "SCUD" ballistic missile that Armenia dropped to Ganja last night, 13 October 2020, retrieved 17 October 2020

- ^ Agencies (17 October 2020). "Nagorno-Karabakh: Azerbaijan says 12 civilians killed by shelling in Ganja". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "The Fight for Nagorno-Karabakh: Documenting Losses on the Sides of Armenia and Azerbaijan". 2020.

- ^ Gary K. Bertsch (2000). Crossroads and conflict: security and foreign policy in the Caucasus and Central Asia. Routledge. p. 173. ISBN 0415922747.

- ^ "Обнародован ежегодный отчет по экспорту и импорту вооружений в Регистре обычных вооружений ООН (United Nations Register of Conventional Arms)". Memo.ru. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ "Iran sold Scud missiles to Congolese" By Bill Gertz THE WASHINGTON TIMES 22 November 1999, page 1.

- ^ "Fears-Myanmar-buying-missiles-from-North-Korea-raise-Canberra's-alarm". 5 February 2018.

- ^ "Myanmar-'buying'-N-Korean-arms". 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Syria's Scientific Studies and Research Center". storymaps.com. 20 October 2020. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ^ "SS-1 "Scud"". Missile Threat. Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "Trade Registers". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "Въпрос на празника: Кой унищожи ракетния щит на България?". Pan.bg. 30 December 2015. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ a b "East German army unit finds skills still in demand after reunification". Deutsche Welle. 16 August 2010. Archived from the original on 12 September 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- ^ "Photographic image of Scud-B missiles" (JPG). Img.index.hu. 1995. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- ^ a b "Scud – Iraq Special weapons". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Khan, Feroz (7 November 2012). Eating Grass: The Making of the Pakistani Bomb. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-8480-1. Retrieved 22 September 2023.

- ^ Cooper, Tom (2017). Hot Skies Over Yemen, Volume 1: Aerial Warfare Over the South Arabian Peninsula, 1962-1994. Solihull, UK: Helion & Company Publishing. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-912174-23-2.

- ^ "Единая Россия: США помогли Украине утилизировать 185 ракет "Скад"". Archived from the original on 17 July 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Zaloga, Steven; Illustrated by Jim Laurier and Lee Ray (2006). Scud Ballistic Missile Launch Systems 1955–2005. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-947-9.

- Yousaf, Mohammad; Adkin, Mark (2001). Afghanistan-the bear trap. Casemate. ISBN 0-9711709-2-4.

External links

[edit]- Jane's Intelligence Review (June 1995). "Strategic Delivery Systems". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 5 September 2008.

- "Iraq's Scud Ballistic Missiles". GulfLink. 25 July 2000. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- R-11 / SS-1B SCUD-A

- A Lucid Interval