Sarah Gilbert

Sarah Gilbert | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 1962 (age 62) Kettering, Northamptonshire, England |

| Alma mater | University of East Anglia (BSc) University of Hull (PhD) |

| Known for | Vaccinology |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | Albert Medal (2021) Princess of Asturias Award (2021) King Faisal Prize (2023) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Vaccines[1] |

| Institutions | University of Oxford Vaccitech Delta Biotechnology Leicester Biocentre Brewing Industry Research Foundation Christ Church, Oxford |

| Thesis | Studies on lipid accumulation and genetics of Rhodosporidium toruloides (1986) |

| Doctoral advisor | Colin Ratledge, Dr M. Keenan |

| Website | www |

Dame Sarah Catherine Gilbert DBE FRS (born April 1962) is an English vaccinologist who is a Professor of Vaccinology at the University of Oxford and co-founder of Vaccitech.[2][3][4][5][6] She specialises in the development of vaccines against influenza and emerging viral pathogens.[7] She led the development and testing of the universal flu vaccine, which underwent clinical trials in 2011.

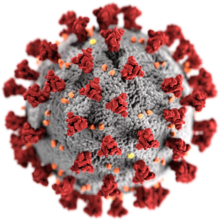

In January 2020, she read a report on ProMED-mail about four people in China suffering from a strange kind of pneumonia of unknown origin in Wuhan.[8] Within two weeks, a vaccine had been designed at Oxford against the new pathogen, which later became known as COVID-19.[9] On 30 December 2020, the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine she co-developed with the Oxford Vaccine Group was approved for use in the UK.[10] More than 3 billion doses of the vaccine were supplied to countries worldwide.[11]

Early life and education

[edit]Sarah Catherine Gilbert was born in Kettering, Northamptonshire. Her father was an office manager for a shoemakers and her mother was a primary school teacher.[12] Gilbert attended Kettering High School for Girls, where she realised that she wanted to work in medicine.[13][14] She earned nine O-Levels with six A grades.[13] She graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in biological sciences from the University of East Anglia (UEA) in 1983.[15] While at UEA she began playing the saxophone, which she would practise in the woods around the UEA Broad so as not to disturb others in her halls.[13][16]

She moved to the University of Hull for her doctoral degree, where she investigated the genetics and biochemistry of the yeast Rhodosporidium toruloides, graduating with a PhD in 1986.[17][14]

Research and career

[edit]After earning her doctoral degree, Gilbert worked as a postdoctoral researcher in industry at the Brewing Industry Research Foundation before moving to the Leicester Biocentre. In 1990, Gilbert joined Delta Biotechnology, a biopharmaceutical company that manufactured drugs in Nottingham.[14][18] In 1994, Gilbert returned to academia, joining the laboratory of Adrian V. S. Hill. Her early research considered host–parasite interactions in malaria. She became a University lecturer in 1999 and she was made a Reader in Vaccinology at the University of Oxford in 2004.[14]

She was made Professor at the Jenner Institute in 2010. With the support of the Wellcome Trust, Gilbert started work on the design and creation of novel influenza vaccinations.[14] In particular, her research considers the development and preclinical testing of viral vaccinations, which embed a pathogenic protein inside a safe virus.[19][20] These viral vaccinations induce a T cell response, which can be used against viral diseases, malaria and cancer.[19]

Gilbert was involved with the development and testing of the universal flu vaccine. Unlike conventional vaccinations, the universal flu vaccine did not stimulate the production of antibodies, but instead triggers the immune system to create T cells that are specific for influenza.[21] It makes use of one of the core proteins (nucleoprotein and matrix protein 1) inside the Influenza A virus, not the external proteins that exist on the outside coat.[22]

As the immune system weakens with age, conventional vaccinations are not effective for elderly. The universal flu vaccine does not need to be reformatted every year and stops people from needing a seasonal flu vaccine. Her first clinical trials, which were in 2008, made use of the Influenza A virus subtype H3N2, and included daily monitoring of the patient's symptoms.[22][23] It was the first study that it was possible to stimulate T cells in response to a flu virus, and that this stimulation would protect people from getting the flu.[22] Her research has demonstrated that the adenoviral vector ChAdOx1 can be used to make vaccinations that are protective against Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) in mice and able to induce immune response against MERS in humans.[24][25] The same vector was also used to create a vaccine against Nipah which was effective in hamsters (but never proven in humans),[26] in addition to a potential vaccine for Rift Valley Fever that was protective in sheep, goats, and cattle (but not proven in humans).[27]

Gilbert has been involved with the development of a new vaccination to protect against coronavirus since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.[28][29][30][2] She leads the work on this vaccine candidate alongside Andrew Pollard, Teresa Lambe, Sandy Douglas, Catherine Green and Adrian Hill.[31] As with her earlier work, the COVID-19 vaccine makes use of an adenoviral vector, which stimulates an immune response against the coronavirus spike protein.[28][29] Plans were announced to start animal studies in March 2020, and recruitment began of 510 human participants for a phase I/II trial on 27 March.[32][33][34]

In April 2020, Gilbert was interviewed about the developments by Andrew Marr on BBC television.[35] That same month, Gilbert was reported as saying that her candidate vaccine could be available by September 2020,[36] if everything goes to plan with the clinical trial, which has received funding from sources such as the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations.[37] Gilbert delivered an update in September 2020 that the vaccine, AZD1222, was being produced by AstraZeneca while phase III trials were ongoing.[38] Because of her vaccine research, Gilbert featured on The Times' 'Science Power List' in May 2020.[39]

In 2021, Gilbert and Catherine Green published Vaxxers: the inside story of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine and the race against the virus.[40][41]

Recognition

[edit]Gilbert was the subject of BBC Radio 4's The Life Scientific in September 2020.[42] She was also on the list of the BBC's 100 Women announced on 23 November 2020,[43] and became a senior associated research fellow at Christ Church, Oxford.[44] Gilbert was awarded the Rosalind Franklin medal for her services to science by Humanists UK at its annual Rosalind Franklin Lecture on 5 March 2021,[45] at which she delivered a lecture titled ‘Racing against the virus’. The lecture detailed the history of the science of vaccination and recounted the progress of the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine.[46]

In June 2021, Gilbert received a standing ovation at the 2021 Wimbledon Championships.[47] In 2021, as a role model (Barbie Shero), Sarah Gilbert had a Barbie doll made in her honour by the toy manufacturer Mattel.[48][49]

Awards

[edit]- 2021 – Humanists UK Rosalind Franklin Medal[46]

- 2021 – Albert Medal of the Royal Society of Arts[50]

- 2021 – Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in the 2021 Birthday Honours for services to science and to public health in COVID-19 vaccine development[51]

- 2021 – Princess of Asturias Award for Technical & Scientific Research[52]

- 2021 – Royal Society of Medicine Gold Medal[53]

- 2022 – Honorary doctorate of science from the University of East Anglia[54]

- 2022 – Honorary degree from the University of Bath[55]

- 2023 – King Faisal Prize in Medicine[56]

- 2023 – Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS)[57]

Personal life

[edit]Gilbert gave birth to triplets in 1998. Her partner gave up his career to be their primary parent.[14] As of 2020[update], all of the triplets are studying biochemistry at university.[12]

Selected publications

[edit]Gilbert has an h-index of 105 according to Google Scholar.[1] Her publications include:[58][59]

- Merryn Voysey; Sue Ann Costa Clemens; Shabir A Madhi; et al. (8 December 2020). "Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK". The Lancet. 397 (10269): 99–111. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32661-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7723445. PMID 33306989. Wikidata Q104286457.

- Schneider J; Sarah Gilbert; Blanchard TJ; et al. (1 April 1998). "Enhanced immunogenicity for CD8+ T cell induction and complete protective efficacy of malaria DNA vaccination by boosting with modified vaccinia virus Ankara". Nature Medicine. 4 (4): 397–402. doi:10.1038/NM0498-397. ISSN 1078-8956. PMID 9546783. S2CID 11413461. Wikidata Q44138669.

- McShane, H; Pathan, A A; Sander, C R; Keating, S M; Gilbert, S C; Huygen, K; Fletcher, H A; Hill, A V S (December 2004). "Erratum: Recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara expressing antigen 85A boosts BCG-primed and naturally acquired antimycobacterial immunity in humans". Nature Medicine. 10 (12): 1397. doi:10.1038/nm1204-1397a. ISSN 1078-8956.

- Samuel J McConkey; William H H Reece; Vasee S Moorthy; et al. (25 May 2003). "Enhanced T-cell immunogenicity of plasmid DNA vaccines boosted by recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara in humans". Nature Medicine. 9 (6): 729–735. doi:10.1038/NM881. ISSN 1078-8956. PMID 12766765. S2CID 6670274. Wikidata Q45723463.

- Sarah Gilbert; Plebanski M; Gupta S; et al. (1 February 1998). "Association of malaria parasite population structure, HLA, and immunological antagonism". Science. 279 (5354): 1173–1177. Bibcode:1998Sci...279.1173G. doi:10.1126/SCIENCE.279.5354.1173. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 9469800. Wikidata Q47826329.

- Katie J. Ewer; Tommy Rampling; Tommy Rampling; et al. (28 January 2015). "A Monovalent Chimpanzee Adenovirus Ebola Vaccine Boosted with MVA". The New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (17): 1635–1646. doi:10.1056/NEJMOA1411627. hdl:10044/1/83613. ISSN 0028-4793. PMC 5798586. PMID 25629663. Wikidata Q24289279.

- Gilbert, Sarah; Green, Catherine (2021). Vaxxers: the inside story of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine and the race against the virus. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 9781529369854.

External links

[edit]- Sarah Gilbert publications indexed by Google Scholar

- Sarah Gilbert on LinkedIn

- Oxford's Professor Sarah Gilbert: "The joys and frustrations of being a Covid vaccine maker". In: La Repubblica, 17 July 2021 (Interview).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Sarah Gilbert publications indexed by Google Scholar

- ^ a b Richard Lane (1 April 2020). "Sarah Gilbert: carving a path towards a COVID-19 vaccine". The Lancet. 395 (10232): 1247. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30796-0. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 7162644. PMID 32305089. Wikidata Q92035270.

- ^ "Sarah Gilbert – Nuffield Department of Medicine". University of Oxford. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Professor Sarah Gilbert". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 2 July 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Professor Sarah Gilbert | University of Oxford". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 10 February 2020.

- ^ "Our Team". vaccitech.co.uk. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ "Professor Sarah Gilbert | Hic Vac". hic-vac.org.

- ^ Gilbert, Sarah; Green, Catherine (2021). Vaxxers : the inside story of the Oxford vaccine and the race against the virus. London. ISBN 978-1529369854.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ McKie, Robin (4 July 2021). "Centre Court ovations, limbo-dancing grans – it's all been humbling, say Oxford vaccine creators". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Covid-19: Oxford-AstraZeneca coronavirus vaccine approved for use in UK". BBC News. BBC. 30 December 2020. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "AstraZeneca withdraws Covid-19 vaccine, citing low demand". CNN. Retrieved 9 May 2024.

- ^ a b Cookson, Clive (24 July 2020). "Sarah Gilbert, the researcher leading the race to a Covid-19 vaccine". Financial Times. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Coronavirus vaccine: Who is Professor Sarah Gilbert?". Newsround. 24 November 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Admin. "Professor Sarah Gilbert". Working for NDM. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "The UEA graduate leading hunt for coronavirus vaccine". Eastern Daily Press. 23 April 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "UEA alumni in 2020". University of East Anglia. Retrieved 28 June 2021.

- ^ Gilbert, Sarah Catherine (1986). Studies on lipid accumulaltion and genetics of Rhodosporidium toruloides. jisc.ac.uk (PhD thesis). University of Hull. OCLC 499901226. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.381881.

- ^ "Vaccine matters: Can we cure coronavirus?". Science Magazine. 12 August 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Sarah Gilbert: Viral Vectored Vaccines — Nuffield Department of Medicine". University of Oxford. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "Professor Sarah Gilbert | Hic Vac". hic-vac.org. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "World-First Trial for Universal Flu Vaccine". Splice. 11 October 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ a b c Jha, Alok (6 February 2011). "Flu breakthrough promises a vaccine to kill all strains". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "Sarah Gilbert — The Jenner Institute". jenner.ac.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Vincent J Munster; Daniel Wells; Teresa Lambe; et al. (16 October 2017). "Protective efficacy of a novel simian adenovirus vaccine against lethal MERS-CoV challenge in a transgenic human DPP4 mouse model". NPJ Vaccines. 2: 28. doi:10.1038/S41541-017-0029-1. ISSN 2059-0105. PMC 5643297. PMID 29263883. Wikidata Q47147430.

- ^ "New MERS Coronavirus vaccine clinical trial starts in Saudi Arabia". www.vaccitech.co.uk. 20 December 2019. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ Neeltje van Doremalen; Teresa Lambe; Sarah Sebastian; et al. (6 June 2019). "A single-dose ChAdOx1-vectored vaccine provides complete protection against Nipah Bangladesh and Malaysia in Syrian golden hamsters". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 13 (6): e0007462. doi:10.1371/JOURNAL.PNTD.0007462. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 6581282. PMID 31170144. Wikidata Q64917294.

- ^ George M Warimwe; Joseph Gesharisha; B Veronica Carr; et al. (5 February 2016). "Chimpanzee Adenovirus Vaccine Provides Multispecies Protection against Rift Valley Fever". Scientific Reports. 6: 20617. Bibcode:2016NatSR...620617W. doi:10.1038/SREP20617. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4742904. PMID 26847478. Wikidata Q36548980.

- ^ a b "Two groups of UK scientists in race to develop coronavirus vaccine". London Evening Standard. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ a b "Vaccine trials among recipients of £20 million coronavirus research investment". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "Oxford team to begin novel coronavirus vaccine research | University of Oxford". University of Oxford. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "COVID-19 Vaccine Trials | COVID-19". covid19vaccinetrial.co.uk. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Sample, Ian (19 March 2020). "Trials to begin on Covid-19 vaccine in UK next month". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ Robson, Steve (20 March 2020). "British scientists hope to start coronavirus vaccine trials next month". manchestereveningnews.co.uk. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ^ "UK scientists enrol volunteers for coronavirus vaccine trial". The Guardian. 17 March 2020.

- ^ "Prof Sarah Gilbert: Coronavirus vaccine trials to start within days". The Andrew Marr Show. UK. 19 April 2020. Retrieved 19 April 2020.

- ^ hermesauto (11 April 2020). "Coronavirus vaccine could be ready in six months, says UK scientist". The Straits Times. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Stephanie Baker (30 March 2020). "How Top Scientists Are Racing to Beat the Coronavirus". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 11 April 2020.

- ^ Lovett, Samuel (1 September 2020). "'You just get on with it': The Oxford professor carrying the world's hopes of a coronavirus vaccine". The Independent. Retrieved 8 September 2020.

- ^ Franklin-Wallis, Oliver (23 May 2020). "From pandemics to cancer: the science power list". The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ Honigsbaum, Mark (11 July 2021). "Vaxxers by Sarah Gilbert and Catherine Green; Until Proven Safe by Geoff Manaugh and Nicola Twilley – reviews". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 June 2022.

- ^ Ledford, Heidi (5 August 2021). "The COVID vaccine makers tell all". Nature. 596 (7870): 29–30. Bibcode:2021Natur.596...29L. doi:10.1038/d41586-021-02090-9. S2CID 236883504.

- ^ Presenter: Jim Al-Khalili; Producer: Anna Buckley (15 September 2020). "Sarah Gilbert on developing a vaccine for Covid-19". The Life Scientific. BBC. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ "BBC 100 Women 2020: Who is on the list this year?". BBC News. 23 November 2020. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

- ^ "e-Matters 25th February 2021". www.chch.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 9 September 2021.

- ^ Gilbert, Sarah (2021). "Racing against the virus". The Rosalind Franklin Lecture. YouTube. Retrieved 7 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Vaccine creator Professor Sarah Gilbert delivers Rosalind Franklin Lecture to thousands". Humanists UK. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ Duncan, Conrad (28 June 2021). "Wimbledon crowd gives standing ovation to Oxford Covid vaccine developer". The Independent. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ "Vaccinologist Barbie: Prof Sarah Gilbert honoured with a doll". the Guardian. 4 August 2021.

- ^ Ross, Deborah (24 May 2023). "Your Sarah Gilbert doll isn't realistic, Mattel. I want a Pay Gap Barbie" – via www.thetimes.co.uk.

- ^ Oxford vaccine creator Professor Sarah Gilbert awarded RSA Albert Medal www.ox.ac.uk, Accessed 23 March 2021

- ^ "No. 63377". The London Gazette (Supplement). 12 June 2021. p. B8.

- ^ IT, Developed with webControl CMS by Intermark. "Katalin Karikó, Drew Weissman, Philip Felgner, Uğur Şahin, Özlem Türeci, Derrick Rossi and Sarah Gilbert - Laureates - Princess of Asturias Awards". The Princess of Asturias Foundation.

- ^ "Royal Society of Medicine welcomes new Honorary Fellows and medal winners". Royal Society of Medicine. 28 July 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ "Covid vaccine co-creator Sarah Gilbert among 2022 UEA honorary graduates". Eastern Daily Press. 20 August 2021. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- ^ "Covid vaccine pioneer Dame Professor Sarah Gilbert receives honorary degree". www.bath.ac.uk. Retrieved 26 June 2024.

- ^ King Faisal Prize 2023

- ^ "Sarah Gilbert". royalsociety.org. Retrieved 14 May 2023.

- ^ Sarah Gilbert publications from Europe PubMed Central

- ^ Publications by Sarah Gilbert at ResearchGate

- 1962 births

- Living people

- Alumni of the University of East Anglia

- Alumni of the University of Hull

- Academics of the University of Oxford

- 20th-century English women scientists

- Vaccinologists

- Influenza researchers

- COVID-19 pandemic in England

- 20th-century British scientists

- 21st-century English women scientists

- 21st-century British scientists

- Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire

- Recipients of Princess of Asturias Awards

- People associated with Christ Church, Oxford

- Vaccination advocates

- Fellows of the Royal Society