Elmina Castle

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official name | Elmina Castle (St. George's Castle / Fort St. Jorge) |

| Location | Elmina, Central Region, Ghana |

| Part of | Forts and Castles, Volta, Greater Accra, Central and Western Regions |

| Criteria | Cultural: (vi) |

| Reference | 34-011 |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| Coordinates | 5°04′57″N 1°20′53″W / 5.0826°N 1.3481°W |

Elmina Castle was erected by the Portuguese in 1482 as Castelo de São Jorge da Mina (St. George of the Mine Castle), also known as Castelo da Mina or simply Mina (or Feitoria da Mina), in present-day Elmina, Ghana, formerly the Gold Coast. It was the first trading post built on the Gulf of Guinea, and is the oldest extant European building south of the Sahara.[1]

First established as a trade settlement, the castle later became one of the most important stops on the route of the Atlantic slave trade. The Dutch seized the fort from the Portuguese in 1637, after an unsuccessful attempt in 1596, and took over all of the Portuguese Gold Coast in 1642. The slave trade continued under the Dutch until 1814. In 1872, the Dutch Gold Coast, including the fort, became a possession of the United Kingdom.[2]

The Gold Coast gained its independence as Ghana in 1957 from United Kingdom and now controls the castle.[3] Elmina Castle is a historical site, and was a major filming location for Werner Herzog's 1987 drama film Cobra Verde. The castle is recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site, along with other castles and forts in Ghana, because of its testimony to the Atlantic slave trade.[4][2] It is a major tourist attraction in Ghana.

History

[edit]Pre-Portuguese

[edit]The people living along the West African coast at Elmina around the fifteenth century were presumably Fante, with an uncertain relationship to the modern Akan who came from north of the forests. Among their ancestors were merchants and miners who traded gold to the Mediterranean and Near Eastern worlds from medieval times.

The people on the West African coast were organized into numerous populations that were drawn according to kinship lines. Family was extremely important in society, and family heads were united in communities under a recognized local authority. Along the Gold Coast alone, more than twenty independent kingdom-states existed. Elmina lay between two different Fante kingdoms, Fetu and Eguafo.

West Africans nurtured ancient trade connections to other parts of the world. Common metals trade, iconic artistic forms, and agricultural borrowing show that trans-Saharan and regional coastal connections thrived. The Portuguese in 1471 were the first Europeans to visit the Gold Coast as such, but not necessarily the first sailors to reach the port.

Portuguese arrival

[edit]

|

|

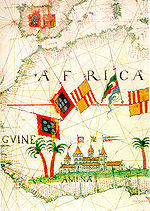

| Two 16th-century maps of the west African coast, showing A mina (the mine) | |

The Portuguese first reached what became known as the Gold Coast in 1471. Prince Henry the Navigator first sent ships to explore the African coast in 1418. The Portuguese had several motives for voyaging south. They were attracted by rumours of fertile African lands that were rich in gold and ivory. They also sought a southern route to India so as to circumvent Arab traders and establish direct trade with Asia.

In line with the strong religious sentiments of the time, another focus of the Portuguese was Christian proselytism. They also sought to form an alliance with the legendary Prester John, who was believed to be the leader of a great Christian nation somewhere far from Europe.

These motives prompted the Portuguese to develop the Guinea trade. They made gradual progress down the African coast, each voyage reaching a point further along than the last. This resulted in a series of trading posts along the route, where fresh water and food could be taken on board. After fifty years of coastal exploration, the Portuguese reached Elmina in 1471, during the reign of King Afonso V. Because Portuguese royalty had lost interest in African exploration as a result of meagre returns, the Guinea trade was put under the oversight of the Portuguese trader, Fernão Gomes. Upon reaching present-day Elmina, Gomes discovered a thriving gold trade already established among the natives and visiting Arab and Berber traders. He established his own trading post. It became known to the Portuguese as "A Mina" (the Mine) because of the gold that could be found there.

Construction of the castle

[edit]

Trade between Elmina and Portugal grew throughout the decade following the establishment of the trading post under Gomes. In 1481, the recently crowned João II decided to build a fort on the coast in order to ensure the protection of this trade, which was once again held as a royal monopoly. King João sent all of the materials needed to build the fort on ten caravels and two transport ships. The supplies, which included everything from heavy foundation stones to roof tiles, were sent, in pre-fitted form, along with provisions for six hundred men. Under the command of Diogo de Azambuja, the fleet set sail on 12 December 1481 and arrived at Elmina, in a village called Of Two Parts[5] a little over a month later, on 19 January 1482. Some historians note that Christopher Columbus was among those to make the voyage to the Gold Coast with this fleet.[6][7][8][9]

Upon arrival, Azambuja contracted a Portuguese trader, who had lived at Elmina for some time, to arrange and interpret an official meeting with the local chief, Kwamin Ansah, interpreted from the Portuguese, "Caramansa". Azambuja told the chief of the great advantages in building a fort, including protection from the very powerful king of Portugal. During the meeting, Azambuja and Chief Kwamin Ansah both participated in a massive peace ritual that included a feast, musicians, and many participants, both Portuguese and native.[5]

Chief Kwamin Ansah, while accepting Azambuja, as he had any other Portuguese trader who arrived on his coast, was wary of a permanent settlement. However, with firm plans already in place, the Portuguese would not be deterred. After offering gifts, making promises, and hinting at the consequences of noncompliance, the Portuguese received Kwamin Ansah's reluctant agreement.

When construction began the next morning, the chief's reluctance was proved to be well-founded. In order to build the fort in the most defensible position on the peninsula, the Portuguese had to demolish the homes of some of the villagers, who consented only after they had been compensated. The Portuguese tried to quarry a nearby rock that the people of Elmina, who were animists, believed to be the home of the god of the nearby River Benya.[5]

Prior to the demolition of the quarry and homes, Azambuja sent a Portuguese crew member, João Bernaldes with gifts to deliver to Chief Kwamin Ansah and the villagers. Azambuja sent brass basins, shawls, and other gifts in hopes of winning the goodwill of the villagers, so they would not be upset during the demolition of their homes and sacred rocks. However, João Bernaldes did not deliver the gifts until after construction began, by which time the villagers became upset upon witnessing the demolition without forewarning or compensation.[5]

In response to this, the local people forged an attack that resulted in several Portuguese deaths. Finally, an understanding was reached. Continued opposition led the Portuguese to burn the local village in retaliation. Even in this tense atmosphere, the first story of the tower was completed after only twenty days. This was the result of having brought so much prefabricated building materials. The remainder of the fort and an accompanying church were completed soon afterwards, despite resistance.[5]

Immediate impact

[edit]

The fort was the first prefabricated building of European origin to have been planned and executed in Sub-Saharan Africa. Upon its completion, Elmina was established as a proper city. Azambuja was named governor, and King João added the title "Lord of Guinea" to his noble titles. São Jorge da Mina took on the military and economic importance that had previously been held by the Portuguese factory at Arguim Island, on the southern edge of Mauritania. At the height of the gold trade in the early sixteenth century, 24,000 ounces of gold were exported annually from the Gold Coast, accounting for one-tenth of the world's supply.

The new fort, signifying the permanent involvement of Europeans in West Africa, had a considerable effect on Africans living on the coast. At the urging of the Portuguese, Elmina declared itself an independent state, whose Governor then took control of the town's affairs. The people of Elmina were offered Portuguese protection against attacks from neighbouring coastal tribes, with whom the Portuguese had much less genial relations, even though they were friendly with the powerful trading nations in the African interior.

If any locals attempted to trade with a nation other than Portugal, the Portuguese reacted with aggressive force, often by forming alliances with the betraying nation's enemies. Hostility between groups increased, and the traditional organization of native societies suffered, especially after the Portuguese introduced them to fire-arms, which made the dominance of the stronger nations easier.

Trade with the Europeans helped make certain goods, such as cloth and beads, more available to the coastal people. European involvement also disrupted traditional trade routes between coastal people and northern people by cutting out the African middlemen. The population of Elmina swelled with traders from other towns hoping to trade with the Portuguese, who gradually established a West African monopoly.

West African slave trade

[edit]

From the outset, the Portuguese authorities determined that São Jorge da Mina would not engage directly in the slave trade, as they did not wish to disrupt the gold mining and trade routes of its hinterland with the wars necessary to capture free people and enslave them. Instead, the Portuguese traded captives with several states/tribes, notably those of the Slave Coast (Benin) and São Tomé. This way, São Jorge da Mina served as a transshipment entrepôt.

By the seventeenth century, most trade in West Africa concentrated on the sale of captives. São Jorge da Mina played a significant part in the West African slave trade. The castle acted as a depot where enslaved Africans were brought in from different Kingdoms in West Africa. The Africans, often captured in the African interior by the slave-catchers of coastal peoples, were sold to Portuguese, and later to Dutch traders in exchange for goods such as textiles and horses.

In 1596, the Dutch made a first unsuccessful attempt at capturing the castle, succeeded by a successful one in 1637,[10] after which it was made the capital of the Dutch Gold Coast. During the period of Dutch control a new, smaller fortress was built on a nearby hill to protect St. George's Castle from inland attacks. This fort was called Fort Coenraadsburg. The Dutch continued the triangular Atlantic slave route until 1814, when they abolished the slave trade, pursuant to the Anglo-Dutch Slave Trade Treaty.

In 1872, the British took over the Dutch territory and the fort pursuant to the Anglo-Dutch Sumatra treaties of 1871.

Renovation

[edit]The castle was extensively restored by the Ghanaian government in the 1990s. Renovation of the castle continues. Today, Elmina's economy is sustained by tourism and fishing. Elmina Castle is preserved as a Ghanaian national museum. The monument was designated as a World Heritage Monument under UNESCO in 1979. It is a place of pilgrimage for many African Americans seeking to connect with their heritage.[11]

3D documentation with terrestrial laser scanning

[edit]In 2006, the Zamani Project documented Elmina Castle with terrestrial 3D laser scanning. The 3D model, a panorama tour, elevations, sections and plans of Elmina Castle are available on the project's website.[12] The non-profit research group specialises in 3D digital documentation of tangible cultural heritage. The data generated by the Zamani Project creates a permanent record that can be used for research, education, restoration, and conservation.[13][14][15]

Gallery

[edit]-

Elmina Castle Interior View of Church

-

Elmina Castle Interior

-

Elmina Castle Male and Female Slave Entrances

-

Elmina Castle Memorial Plaque

-

Elmina Castle Slave Export Gate

-

Elmina Castle Slave Holding Cell

-

Elmina Castle Slave Holding Cell

-

Elmina Castle Gun Defences

-

Elmina Castle

-

Remnants of the docks at Elmina Castle

-

Solitary Confinement Rooms at Elmina Castle

-

"Female Dungeon" - Elmina Castle in 1995

-

Dungeon - Elmina Castle, 1995

-

Elmina Castle

-

Elmina Castle, Central region

-

Elmina Castle

In popular culture

[edit]Scenes from a season 6 episode of the FX series Snowfall were shot in Elmina Castle. The title of the episode, "Door of No Return", is a reference to the symbolic door that millions of Africans were pushed through when they entered a life of slavery through castles like this.[16][17]

Elmina Castle also featured prominently in the 2015 Danish film Guldkysten (Gold Coast).[18]

Works

[edit]See also

[edit]- Diaspora tourism

- Door of Return

- List of castles in Ghana

- Year of Return, Ghana 2019

- Dutch government school of Elmina

References

[edit]- ^ "Elmina Castle - Castles, Palaces and Fortresses". www.everycastle.com. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Forts and Castles, Volta, Greater Accra, Central and Western Regions". whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ "Elmina Castle - Ghana". ElminaCastle.info. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ "Elmina Castle, Ghana". www.ghana.photographers-resource.com. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e The Portuguese In West Africa, Cambridge University Press, 1950, p. 93.

- ^ Wada, Kayomi (11 January 2010), "El Mina São Jorge da Mina", BlackPast. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- ^ Hair, P. E. H. (1995). "Was Columbus' First Very Long Voyage a Voyage from Guinea?" History in Africa, vol. 22, pp. 223–237. doi:10.2307/3171915.

- ^ "Ghana History - Early Contact", GlobalSecurity.org.

- ^ Asomaning, Hannah (3 January 2006), "Elmina Deserves World's Attention", GhanaWeb.

- ^ Lawrence, A. W. (1963). Trade Castles & Forts of West Africa. London: Jonathan Cape. p. 36.

- ^ Mensah, Ishmael (3 July 2015). "The roots tourism experience of diaspora Africans: A focus on the Cape Coast and Elmina Castles". Journal of Heritage Tourism. 10 (3): 213–232. doi:10.1080/1743873X.2014.990974. ISSN 1743-873X. S2CID 145169991.

- ^ "Site - Elmina Castle". zamaniproject.org. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Rüther, Heinz. "An African heritage database, the virtual preservation of Africa's past" (PDF). www.isprs.org.

- ^ Rajan, Rahim S.; Rüther, Heinz (30 May 2007). "Building a Digital Library of Scholarly Resources from the Developing World: An Introduction to Aluka". African Arts. 40 (2): 1–7. doi:10.1162/afar.2007.40.2.1. ISSN 0001-9933. S2CID 57558501.

- ^ Rüther, Heinz; Rajan, Rahim S. (December 2007). "Documenting African Sites: The Aluka Project". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 66 (4). University of California Press: 437–443. doi:10.1525/jsah.2007.66.4.437. JSTOR 10.1525/jsah.2007.66.4.437. Archived from the original on 24 September 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ Okantah, Ile-Ife (1 March 2023). "Snowfall Recap: Welcome Home, Leon". Vulture. Archived from the original on 2 March 2023. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Ryan, Orla (20 March 2007). "Door of no return opens up Ghana's slave past". Reuters. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ "Guldkysten (2015)". www.danskefilm.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 1 November 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Andrea, Alfred J., and James H. Overfield. "African Colonialism", The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Fifth Edition, Volume 2. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005.

- Bruner, Edward M. "Tourism in Ghana: The representation of slavery and the return of the Black Diaspora", American Anthropologist 98 (2): 290–304.

- Claridge, Walton W. A History of the Gold Coast and Ashanti, Second Edition. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd, 1964.

- Daaku, Kwame Yeboa. Trade & Politics on the Gold Coast 1600–1720. London: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- DeCorse, Christopher R. An Archaeology of Elmina: Africans and Europeans on the Gold Coast, 1400–1900. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2001.

- Doortmont, Michel R.; Jinna Smit (2007). Sources for the Mutual History of Ghana and the Netherlands. An annotated guide to the Dutch archives relating to Ghana and West Africa in the Nationaal Archief, 1593–1960s. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15850-4.

- Hair, P. E. H. The Founding of the Castelo de São Jorge da Mina: an analysis of the sources. Madison: University of Wisconsin, African Studies Program, 1994. ISBN 0-942615-21-2

- Pacheco, Duarte. Esmeraldo de situ orbis, c. 1505–1508.

- World Statesmen-Ghana

External links

[edit]- www.zamaniproject.org Offers a 3D model, a panorama tour, elevations, sections and plans of Elmina Castle.

- Ghana-pedia webpage - São Jorge da Mina

- Elmina

- 15th century in Ghana

- 15th-century establishments in Africa

- 1482 establishments in the Portuguese Empire

- Buildings and structures completed in 1482

- Castles in Ghana

- Dutch Gold Coast

- Dutch slave trade

- Forts in Ghana

- Portuguese colonial architecture in Ghana

- Portuguese Gold Coast

- Portuguese slave trade

- Slave forts

- Slavery museums

- World Heritage Sites in Ghana