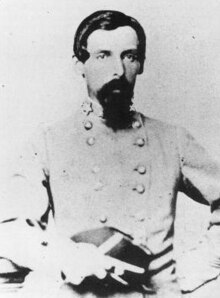

Samuel Garland Jr.

Samuel Garland Jr. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | December 16, 1830 Lynchburg, Virginia |

| Died | September 14, 1862 (aged 31) South Mountain, Maryland |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | Virginia Militia Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1859–61 (Militia) 1861–62 (CSA) |

| Rank | Brigadier General |

| Commands | 11th Virginia Infantry Regiment Garland's Brigade |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

| Relations | James Madison (great-grandnephew) James Longstreet (cousin by marriage) Gilbert S. Meem (brother-in-law) John Garland (nephew) |

Samuel Garland Jr. (December 16, 1830 – September 14, 1862) was an American attorney from Virginia and Confederate general during the American Civil War. He was killed in action during the Maryland Campaign while defending Fox's Gap at the Battle of South Mountain.

Early life

[edit]The great-grandnephew of James Madison, Garland was born in Lynchburg to Maurice H. Garland and Caroline M. Garland, the only daughter of Alexander Spotswood Garland. His father was a well-known attorney of S. & M. H. Garland law firm, but died on September 14, 1840, when his son was ten years old. Garland was placed in a private classical school in the Nelson County. When he turned fourteen, he entered Randolph Macon College, where he studied for a year.

On October 22, 1846, he was matriculated at Virginia Military Institute, where he organized a literary society, and was graduated third in his class on July 4, 1849.[1] Garland decided to pursue legal career and studied law at the University of Virginia, and then practiced it in Lynchburg. In 1856, he married Elizabeth Campbell Meem, daughter of John G. Meem of Lynchburgh and fathered one child, a son also named Samuel.[2] Garland helped organize a militia company, the Lynchburg Home Guard, after John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry. He was elected as company's captain.[3] He also lectured on natural law at Lynchburg College.[4]

He continued as an attorney until his home state seceded from the Union in the spring of 1861. His militia company joined the 11th Virginia Infantry, and Garland was commissioned by Governor John Letcher as the regiment's colonel.[5] However, personal tragedy soon struck, as on June 12, 1861, his wife died from influenza, and on July 31, 1861, Garland's four-year-old son Sammie would also succumb to the influenza epidemic.[2] Garland's wife and son were buried side by side in the Presbyterian Cemetery in Lynchburg.

Civil War

[edit]A grieving Garland saw action in July at First Bull Run. He gained a reputation for fearlessness under fire, which some believed stemmed from a death wish.[6] He also saw action at Dranesville, Battle of Oak Grove, Battle of Beaver Dam Creek, Battle of Seven Pines, Battle of Gaines' Mill, Battle of Malvern Hill, and Williamsburg, having been wounded at the latter by a ball in the elbow on May 5, 1862.[7][8] For bravery in battles and commanding skills, on May 23, 1862, Garland was promoted to brigadier general.[9] After promotion, Garland distinguished himself in the Peninsula Campaign (March–July 1862) and the Seven Days Battles (June 25-July 1, 1862).[10]

Battle of Seven Pines

[edit]In the Battle of Seven Pines Garland was at the left wing of the Confederate army supporting Gen. George B. Anderson. Each wing of the army was preceded by a regiment deployed as skirmishers. One particular problem with the Confederate battle plan was that the right wing of the army was delayed by a quarter of an hour waiting for the relieving force. This exposed Garland and Anderson to the whole Yankee force. A few hundred yards after the right wing caught up they came under fire. The location for this battle was majorly important in determining the outcome. It had recently rained and the soldiers were marching through deep mud in a densely packed forest. As the battle proceeded, both sides suffered a number of losses. Eventually, Gen. Robert E. Rodes managed to get behind and flank the Federal troops, capturing six artillery pieces. He used these guns to turn back fresh Yankee soldiers that hoped to retake lost positions and thus won the battle.[11]

Battle of Gaines' Mill

[edit]The Battle of Gaines' Mill waged east of Mechanicsville was the third of the Seven Days Battles. At first, Garland and his men had to survive artillery fire while waiting out for the enemy in rifle pits on Williamsburg Road as Garland and his troops were assigned to support Generals Lewis Armistead and Ambrose R. Wright forces. At about 2 a.m. they began moving on the enemy. They stopped and hid at a position on the Mechanicsville turnpike just behind the crest of the commanding hill and waited there for Maj. Gen. A. P. Hill to attack the other side of Mechanicsville. Garland and his troops were hit with heavy artillery fire from Beaver Dam Creek. Eventually, the afternoon rolled around and Gen. Hill arrived and began to attack the Federals from the other side. They were then given orders to advance, but they first had to defeat the enemy at Beaver Creek Dam before they could move through. The Federals had artillery and a small amount of infantry so Garland's troops attacked until the Federals retreated. This happened early on the 27th of June. Garland's men then advanced to their next positions, but before they could arrive they ran into the Federal troops at New Cold Harbor. The battle raged on for some time. Soon Maj. Gen. Stonewall Jackson arrived and began rearranging the formations of the troops. Then Garland along with a couple other battalions crossed an open field into the woods. Here they found an exposed enemy flank and began preparing to attack it. As soon as Gen. Hill joined up with them they commenced the attack on the exposed enemy flank. The Federals quickly gave up and began to flee. At one point they attempted a second stand, but even this was broken quickly as Garland and his men had momentum on their side. This ended the battle with a victory for Garland and the Confederates. In the Battle of Gaines' Mill, Garland successfully attacked the Federal flank and took many prisoners earning an outstanding reputation in the Confederate army.[2]

Battle for Fox's Gap

[edit]In the beginning of Maryland Campaign General Robert E. Lee separated the Army of Northern Virginia into two corps and gave them different tactical tasks. The First corps under Maj. Gen. James Longstreet moved from Frederick to Hagerstown and Boonsboro while the Second corps under "Stonewall" Jackson was given task to seize Harpers Ferry with its arsenals and supplies. Garland's brigade was a part of Maj. Gen. Daniel H. Hill's division in the Second Corps, and had a secondary objective to defend "Stonewall" Jackson's rear echelons. Garland commanded five North Carolina volunteer regiments, the 5th, the 12th, the 13th, the 20th and the 23rd, which were positioned in the South Mountain range guarding the passes. However, unbeknownst to the Confederates, Lee's strategic intentions became known to the opposite side, and after "Stonewall" Jackson's troops mounted the siege of Harpers Ferry, the Union forces struck back starting the Battle of South Mountain also known as the Battle of Boonsboro.

It later turned up that a mislaid copy of Lee's movement order revealing the Confederates' strategic plans for Maryland Campaign—the so-called Special Order 191—was given to Union commander Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan. Emboldened by obtained intelligence, McClellan decided to force his army through the passes in the South Mountain range to surprise Lee's scattered divisions and beat them one by one: one half of Lee's army was at Harpers Ferry and the other—divided between Hagerstown and Boonsboro. After realizing the dangers, Lee ordered Maj. Gen. D. H. Hill to defend the South Mountain passes, i.e., the Boonsboro, or Turner's Gap, the Fox's Gap, and the Crampton's Gap to give him time to bring back the Second corps and pull together the Army of Northern Virginia at Sharpsburg.[12]

On September 14, 1862, Union troops from the Army of the Potomac moved to seize the passes and advance toward Boonsboro where the wagon trains and parks of artillery of the Army of Northern Virginia were kept.[13] McClellan expected to meet with strong opposition at the South Mountain, but in reality the Confederates there were greatly outnumbered by the Federals. The main points of contention were two South Mountain passes, the Turner's Gap and the nearby Fox's Gap, as they provided the shortest access to Boonsboro. Hill wrote in his memoir, The Battle of South Mountain, or Boonsboro: Fighting For Time at Turner's and Fox's Gaps, that after the Federal artillery started firing at 9 a. m. he instructed Garland to defend the National Pike, which was leading through the Turner's Gap towards Boonsboro, at all costs:

The firing had aroused that prompt and gallant soldier, General Garland, and his men were under arms when I reached the pike. I explained the situation briefly to him, directed him to sweep through the woods, reach the road, and hold it at all hazards, as the safety of Lee's large train depended upon its being held. He went off in high spirits and I never saw him again. I never knew a truer, better, braver man. Had he lived, his talents, pluck, energy, and purity of character must have put him in the front rank of his profession, whether in civil or military life.[13]

About 3,000 Federals belonging to General Jacob D. Cox's division from Gen. Jesse L. Reno corps, including Lieutenant-Colonel Rutherford B. Hayes of the 23d Ohio regiment, attacked Garland's men whose number was at "scarce a thousand."[13] The Federals pressed north toward Fox's and Turner's Gaps.[14][15] During the spirited mid-morning engagement at Fox's Gap, Garland was mortally wounded while commanding his men who were defending a stone wall bordering farmer Daniel Wise's field along Old Sharpsburg Road. He died within minutes.[9] Colonel Duncan K. McRae, of the 5th North Carolina Regiment, assumed command after Garland's death.[16] Garland's body was retrieved by Confederate troops and sent down the mountainside. On September 19, 1862, Garland was buried in the Presbyterian Cemetery in his hometown of Lynchburg next to his wife and son.

Family

[edit]Garland's maternal grandmother was Lucinda Rose Garland, a daughter of Dr. R.H. Rose and Frances Madison, who was a sister of President James Madison.[17] His uncle, John Garland, was a U.S. Army general and fought in many different wars including, the War of 1812, Seminole Wars, Mexican–American War, Utah War and very briefly in the American Civil War on the side of the Union.

Remembrance

[edit]

In his official report after the Battle of South Mountain, Garland's commanding officer, Maj. Gen. D.H. Hill memorialized him by writing, "This brilliant service, however, cost us the life of that pure, gallant, and accomplished Christian soldier, General Garland, who had no superiors and few equals in the service."[18]

The Samuel Garland Camp of the United Confederate Veterans was named in his memory, as was the later Garland-Rodes Camp of the successor organization Sons of Confederate Veterans. On September 11, 1993, members of Garland-Rhodes Camp 409, Sons of Confederate Veterans, installed a commemorative marker near the spot of Garland's death on Wise's Field near the earlier 1889 marker erected by Union soldiers of the IX Corps to Gen Jesse L. Reno on Reno Monument Road. Nearby a bronze sculpture with a granite base monument dedicated to the North Carolina troops that held the line there was erected in 2005. The Central Maryland Heritage League works on preservation of the Fox's Gap battlefield as part of the South Mountain State Battlefield Park.[19]

See also

[edit]- General officers in the Confederate States Army

- List of American Civil War generals (Confederate)

- Turner's and Fox's Gaps Historic District

Notes

[edit]- ^ VMI's Civil War Generals: Samuel Garland, Class of 1849, Virginia Military Institute

- ^ a b c "Samuel Garland". Tim Kent's Civil War Tales. 31 December 2014.

- ^ Blackford, Charles M. Annals of the Lynchburg Home Guard. Lynchburg, Va: J.W. Rohr, 1891.

- ^ Johnson, John Lipscomb (1871). The University Memorial: Biographical Sketches of Alumni of the University of Virginia who Fell in the Confederate War. Turnbull Brothers.

- ^ Samuel Garland Civil War Commission Document, Virginia Military Institute

- ^ Richard E. Clem. Confederate general finds peace in battle, Washington Times, August 11, 2006.

- ^ Welsh, Jack D. Medical Histories of Confederate Generals. Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Congressional Edition, Volume 2241. U.S. Government Printing Office. 1884. pp. 639–645.

- ^ a b "From the Peninsula to Maryland: Garland's role in the summer of 1862". National Park Service.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer, James R. Arnold, Roberta Wiener, Paul G. Pierpaoli, and David Coffey. American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2013, p. 745.

- ^ Smith, Gustavus W. The Battle of Seven Pines. New York: C.G. Crawford, 1891.

- ^ "The Battle of South Mountain". Civil War Trust.

- ^ a b c The Battle of South Mountain, or Boonsboro: Fighting For Time at Turner's and Fox's Gaps. By Daniel H. Hill, Lieutenant-General, C.S.A.

- ^ Battle of Fox's Gap map, Civil War Trust

- ^ Battle of South Mountain: Fox's Gap, September 14, 1862, afternoon map, In: Carman, Ezra; Clemens, Thomas, ed. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Vol. 1: South Mountain. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2010. ISBN 978-1-932714-81-4.

- ^ Clark, Walter. Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina, in the Great War 1861-1865. Raleigh: E.M. Uzzell, Printer and Binder. 1901, p. 286.

- ^ John Lipscomb Johnson. The University Memorial: Biographical Sketches of Alumni of the University of Virginia who Fell in the Confederate War. Baltimore, MD: Turnbull Brothers, 1871, pp. 263–264.

- ^ United States War Department. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. OCLC 427057. Series 1, Volume XIX, Chapter XXI, p. 1020.

- ^ Kevin Rawlings. CMHL Rediscovers Its Founding Mission Archived 2015-09-11 at the Wayback Machine

References

[edit]- Blackford, Charles M. Annals of the Lynchburg Home Guard. Lynchburg, Va: J.W. Rohr, 1891.

- Carman, Ezra; Clemens, Thomas, ed. The Maryland Campaign of September 1862, Vol. 1: South Mountain. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2010. ISBN 978-1-932714-81-4.

- Clark, Walter. Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina, in the Great War 1861-1865. Raleigh: E.M. Uzzell, Printer and Binder. 1901

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher, Civil War High Commands. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-8047-3641-1.

- Johnson, John Lipscomb. The University Memorial: Biographical Sketches of Alumni of the University of Virginia who Fell in the Confederate War. Baltimore, MD: Turnbull Brothers, 1871, pp. 263–271.

- Sifakis, Stewart. Who Was Who in the Civil War. New York: Facts On File, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8160-1055-4.

- Smith, Gustavus W. The Battle of Seven Pines. New York: C.G. Crawford, 1891.

- Tucker, Spencer, James R. Arnold, Roberta Wiener, Paul G. Pierpaoli, and David Coffey. American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2013.

- United States War Department. The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. OCLC 427057.

- Warner, Ezra J. Generals in Gray: Lives of the Confederate Commanders. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1959. ISBN 978-0-8071-0823-9.

Further reading

[edit]- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901. Online reference; differs from reference in reference section.

External links

[edit]- Samuel Garland Jr. at Find a Grave

- Samuel Garland, Jr., National Park Service

- Battle of South Mountain: Fox's Gap, The Central Maryland Heritage League

- 1830 births

- 1862 deaths

- American slave owners

- People from Lynchburg, Virginia

- Confederate States Army brigadier generals

- Confederate States of America military personnel killed in the American Civil War

- People of Virginia in the American Civil War

- Virginia lawyers

- Virginia Military Institute alumni

- University of Virginia School of Law alumni

- 19th-century American lawyers