Samuel Gardner Wilder

Samuel Gardner Wilder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Minister of Interior | |

| In office July 3, 1878 – August 14, 1880 | |

| Monarch | Kalākaua |

| Preceded by | John Mott-Smith |

| Succeeded by | John Edward Bush |

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 20, 1831 Leominster, Massachusetts, United States |

| Died | July 28, 1888 (aged 57) Honolulu, Oahu, Kingdom of Hawaii |

| Nationality | Kingdom of Hawaii United States |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Kinaʻu Judd |

| Children | 6 |

| Occupation | Shipping business |

| Signature | |

Samuel Gardner Wilder (June 20, 1831 – July 28, 1888) was an American shipping magnate and politician who developed a major transportation company in the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Life

[edit]Samuel Gardner Wilder was born June 20, 1831, in Leominster, Massachusetts. His father was William Chauncey Wilder (1804–1858) and mother was Harriet Waters (died 1850). They moved to Canada for a few years, and then to New York in 1840, and Chicago in 1844. Part of the California Gold Rush, the family moved west in 1852. He worked for the Adams Express Company which allowed him to travel to and from the coast of California. His first visit to the Hawaiian Islands was in 1856. He married Elizabeth Kinaʻu Judd (1831–1918), daughter of missionary doctor and politician Gerrit P. Judd September 29, 1857 in Honolulu.[1] She was namesake of the native Hawaiian civil leader Elizabeth Kīnaʻu, who was daughter of Kamehameha I.

Business

[edit]

Wilder chartered the clipper ship White Swallow and returned in 1858. He took a load of guano (bird excrement used as fertilizer) from Jarvis Island to New York City,[2] which served as the couple's honeymoon voyage.[3] He then started a sugarcane plantation with his father-in-law (now the Kualoa Ranch) in 1864.[4] He sent for his brother, William Chauncey Wilder (1835–1901)[5] who had served in the cavalry in the American Civil War. The plantation failed by 1868 and William returned to Geneva, Illinois.[6] In 1870 other sugar planters had Wilder sent to China to bring back low-cost workers. He encountered resistance from the British administration in Hong Kong, and only 188 Chinese came as a result.[7]

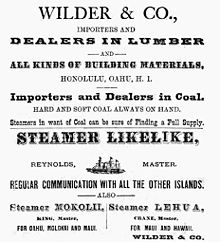

In 1871 he took over the lumber business of James I. Dowsett. He also became agent for the government-owned steamship Kilauea, named for Kīlauea volcano, which ran passenger service between the islands. In 1872 with C. H. Lewers, he established Wilder & Company for the shipping and related businesses.[8] In 1873 his brother William brought out his wife and family to help in the shipping business. After the reciprocity Treaty of 1875, the sugar business boomed, and created demand to use steamships to move the raw sugar to the port of Honolulu where it was taken to the sugar refinery in California owned by Claus Spreckels, who invested in Wilder's company.

In 1877 the government ordered a second steamer Likelike (named for Princess Likelike) from San Francisco. After one voyage, the government promptly sold it to Wilder. The Likelike was about 50% larger than the aged Kilauea, which needed frequent repairs.[9] Part of his agreement was to carry the mail on his ships.[10]

Over time more ships were added to his fleet, and railroads built to meet the ports. The Hawaiian Railroad was constructed from 1881 to 1883.[11] It ran from plantations in the Kohala district of the island of Hawaiʻi to a harbor he built at Māhukona.[12] The company was incorporated as Wilder Steamship Company in 1883.[13]

Politics

[edit]In 1868, Wilder was elected to the House of Representatives of the legislature of the Hawaiian Kingdom. In 1874, King Lunalilo appointed him to the upper House of Nobles of the legislature. Lunalilo died after reigning only one year, so the first job of the 1874 legislature was to elect a new king; Wilder was selected to count and announce the votes.[14] Wilder used his steamer to campaign for David Kalākaua, who won the election in the Legislative Assembly (and subsequently rewarded Wilder with honors), even though Queen Emma was more popular with the people. In 1878, Wilder established the first telephone line on Oahu, from his government office to his lumber business.[15]

Wilder was awarded the Royal Order of Kalākaua and Royal Order of the Crown of Hawaii. On July 3, 1878, Kalākaua appointed him minister of the interior.[16] He was considered the most powerful member of what was then called the "Wilder Cabinet". Although concerned with efficiency in administration and reducing government debt instead of ideology, one of his projects was to lay the cornerstone of a new royal residence, ʻIolani Palace.[17]: 204 On August 14, 1880, the king replaced all his ministers with a controversial and short-lived cabinet headed by Celso Caesar Moreno with John Edward Bush in the interior post.[17]: 214

In 1887, Wilder was elected president of the legislature, although he would leave shortly. In Washington, D.C., he met with diplomat Henry A. P. Carter (who had married Wilder's wife's sister) and US Secretary of State Thomas F. Bayard. Wilder said he supported the monarchy, but was not sure it would last long, and that the US should negotiate for annexation.[17]: 418 He traveled to London to raise money for a railroad venture from Hilo to the Hāmākua District of Hawaiʻi island. However, news of the political crisis leading up to the Bayonet Constitution discouraged investors. The new constitution made the upper house elective for the first time, and he won the 1888 election. He died July 28, 1888. He was buried in Oahu Cemetery.[2]

Legacy

[edit]

The Wilders' children were:[18]

- William Chauncey Wilder was born May 12, 1859, and died August 21, 1868.

- Laura Reed Wilder was born October 17, 1861. On December 27, 1881, she married Charles Leslie Wight in Boston and had five children.

- Gerrit Parmele Wilder was born November 5, 1863. He married Lillian Kimball at Mills College in California on November 7, 1887. After a few years in the family business, he became a horticulturalist in 1898, going on expeditions and publishing several books on plants of the Pacific. He died September 28, 1935.[19]

- Samuel Gardner Wilder was born January 12, 1866. He married Molly Alatau Atkinson on July 20, 1896, and had four children. One of them was also named Samuel Gardner Wilder, born August 8, 1898.

- James Austin "Kimo" Wilder was born May 22, 1868. He married Sarah Harnden on September 12, 1899, at Alameda, California and had two children. He attended Harvard University and Harvard Law School in 1893–1896. He became an artist and founded the first Boy Scout troop in Hawaii[20] with D. Howard Hitchcock, another artist who married Wilder's cousin.[21] He wrote and played a scoutmaster in the 1917 film Knights of the Square Table.[22] His daughter Kinaʻu Wilder (1902–1992) married Charles B. McVay III and had son Kimo Wilder McVay (1927–2001), who managed Don Ho when he popularized the song Tiny Bubbles.[23]

- Helen Kinaʻu Wilder was born November 27, 1869, and married Horace Joseph Craft on May 16, 1899, but they divorced in 1903. She helped re-establish the Hawaiian Humane Society in 1897.[24]

| Hawaii's Big Five |

|---|

Another younger brother, John Knight Wilder (1833–1905) came out to Hawaii, as well as two younger sisters. On May 17, 1864, John married Caroline Crowningburg,[25] who was related to royalty of Maui.[26] Sister Mary Caroline Wilder (1836–1915) married P. P. Shepard. In 1870, sister Harriet Emily Wilder (1842–1904) married Joseph Platt Cooke (1869–1904), great-grandson of Joseph Platt Cooke (1730–1816) and son of Castle & Cooke founder Amos Starr Cooke (1810–1871). Their son, also named Joseph Platt Cooke (1870–1918), married Maud Mansfield Baldwin (1872–1961), daughter of Henry Perrine Baldwin, co-founder of Alexander & Baldwin.[27] This connected the extended family to several of the "Big Five" corporations that dominated the economy of the Territory of Hawaii in the 20th century. His sister-in-law's son George R. Carter (1866–1933) was the second Territorial Governor.

The Wilder Steamship Company merged into the Inter-Island Steam Navigation Company in 1905. The company started the first scheduled commercial airplane service in 1929 as Inter-Island Airways, and became Hawaiian Airlines in 1941.[28]

James A. King, who started as master of Wilder's ships and became superintendent of the Wilder shipping business, named a son Samuel Wilder King, who became Governor of the Territory of Hawaii.[29] Wilder Avenue which runs past the Punahou School at 21°18′10″N 157°49′56″W / 21.30278°N 157.83222°W in the Makiki neighborhood of Honolulu was named for him.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ Hawaiʻi State Archives (2006). "Oahu marriage record (1832–1910)". Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ a b "The Late Hon. S. G. Wilder: Close of a Busy and Useful Life—Some of the Leading Events in Mr. Wilder's Career—The Funeral". The Hawaiian Gazette. July 31, 1888. p. 6. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ William Andrew Emerson (1888). Leominster, Massachusetts, historical and picturesque. The Lithotype publishing company. pp. 185–187.

- ^ Lloyd J. Soehren (2010). "lookup of Wilder ". in Hawaiian Place Names. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ "Honors to the Dead: great Gathering at Funeral of W. C. Wilder". The Hawaiian Gazette. July 16, 1901. p. 6. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ "Hon William C. Wilder". Paradise of the Pacific. 1893. p. 179.

- ^ Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1953). Hawaiian Kingdom 1854-1874, twenty critical years. Vol. 2. University of Hawaii Press. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-87022-432-4.

- ^ George F. Nellist, ed. (1925). "Samuel Gardner Wilder". The Story of Hawaii and Its Builders. Honolulu Star Bulletin.

- ^ John Haskell Kemble. "Pioneer Hawaiian Steamers, 1852-1877". Annual Report. Hawaiian Historical Society. hdl:10524/78.

- ^ "Inter-Island Mail Routes". Post Office in Paradise web site. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ J. C. Condé (1971). Narrow gauge in a kingdom: the Hawaiian Railroad Company, 1878-1897. Glenwood Publishers. ISBN 9780911760101.

- ^ John R. K. Clark (2004). "lookup of Mahukona ". in Hawai'i Place Names: Shores, Beaches, and Surf Sites. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii Press. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ J. A. kennedy (1910). "Inter-Island Transportation in Hawaii". Annual report. Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu. pp. 119–120.

- ^ Jean Dabagh (1974). "King is Elected: One Hundred Years Ago". Hawaiian Journal of History. Vol. 8. Hawaii Historical Society. hdl:10524/112.

- ^ Robert C. Schmitt (1979). "Some Transportation and Communication Firsts in Hawaii". Hawaiian Journal of History. Vol. 13. Hawaii Historical Society. p. 111. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ "Wilder, Samuel G. Sr. office record". state archives digital collections. state of Hawaii. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c Ralph Simpson Kuykendall (1967). Hawaiian Kingdom 1874-1893, the Kalakaua Dynasty. Vol. 3. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-87022-433-1.

- ^ George R. Carter; Mary H. Hopkins, eds. (July 1922). A record of the descendants of Dr. Gerrit P. Judd of Hawaii, March 8, 1829, to April 16, 1922. Hawaiian Historical Society.

- ^ "Who was GP Wilder?". University of Hawaii department of Botany. Archived from the original on June 11, 2011. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ Winston R. Davis (2005). "James Austin Wilder". Sea Scouts · Boy Scouts of America. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ John William Siddall, ed. (1921). Men of Hawaii: being a biographical reference library, complete and authentic, of the men of note and substantial achievement in the Hawaiian Islands. Honolulu Star-Bulletin. p. 425.

- ^ James A. Wilder at IMDb

- ^ John Berger (June 30, 2001). "Kimo McVay, Hawaii's Mr. Show Biz". Honolulu Star Bulletin. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ "E Komo Mai! — Hawaiian Humane Society". official web site. Hawaiian Humane Society. Retrieved July 23, 2010.

- ^ Hawaiʻi State Archives (2006). "Maui marriage record (1842–1910)". Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library. Retrieved September 20, 2010.

- ^ "Lydia Keomailani Called Home to Marry Prince". The Story of Hawaiian Royalty. November 4, 1955. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ Hawaiian Historical Society Genealogical Committee (1916). A Genealogy of the Wilder family of Hawaii. Vol. Series Number 2. Paradise of the Pacific Press. pp. 1–7.

- ^ "Hawaiian Airlines 75 Years of Service - Timeline". official web site. Hawaiian Airlines. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ Howard Brett Melendy; Rhoda Armstrong Hackler (May 1999). Hawaii, America's sugar territory, 1898-1959. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-7998-2.

- ^ Mary Kawena Pukui; Samuel Hoyt Elbert; Esther T. Mookini (2004). "lookup of Wilder ". in Place Names of Hawai'i. Ulukau, the Hawaiian Electronic Library, University of Hawaii Press. Retrieved September 21, 2010.

Further reading

[edit]- Mifflin Thomas (October 1983). Schooner from windward: two centuries of Hawaiian interisland shipping. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0799-3.

- Elizabeth Leslie Wight (1909). The memoirs of Elizabeth Kinau Wilder. Pacific Press.

- Kinau Wilder (1978). The Wilders of Waikiki. Topgallant Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-914916-28-4.

External links

[edit]- Thomas A. Edison, Inc. (1906). "S.S. Kinau landing passengers, Mahukona, Hawaii". US Library of Congress. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- Thomas A. Edison, Inc. (1906). "Arrival, Mahukona Express, Kohala, Hawaii". US Library of Congress. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- "Minor light of Hawai'i - Mahukona, HI". Lighthouse friends web site. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- 1831 births

- 1888 deaths

- People from Leominster, Massachusetts

- Businesspeople from Hawaii

- Hawaiian Kingdom politicians

- Members of the Hawaiian Kingdom House of Representatives

- Members of the Hawaiian Kingdom Privy Council

- Members of the Hawaiian Kingdom House of Nobles

- Hawaiian Kingdom Interior Ministers

- Jarvis Island

- 19th-century American businesspeople