Salmonella

| Salmonella | |

|---|---|

| |

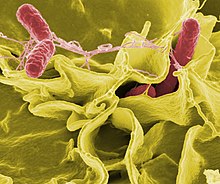

| Color-enhanced scanning electron micrograph showing Salmonella Typhimurium (red) invading cultured human cells | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Enterobacterales |

| Family: | Enterobacteriaceae |

| Genus: | Salmonella Lignières, 1900 |

| Species and subspecies[1] | |

| |

Salmonella is a genus of rod-shaped, (bacillus) gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two known species of Salmonella are Salmonella enterica and Salmonella bongori. S. enterica is the type species and is further divided into six subspecies[2][3] that include over 2,650 serotypes.[4] Salmonella was named after Daniel Elmer Salmon (1850–1914), an American veterinary surgeon.

Salmonella species are non-spore-forming, predominantly motile enterobacteria with cell diameters between about 0.7 and 1.5 μm, lengths from 2 to 5 μm, and peritrichous flagella (all around the cell body, allowing them to move).[5] They are chemotrophs, obtaining their energy from oxidation and reduction reactions, using organic sources. They are also facultative anaerobes, capable of generating adenosine triphosphate with oxygen ("aerobically") when it is available, or using other electron acceptors or fermentation ("anaerobically") when oxygen is not available.[5]

Salmonella species are intracellular pathogens,[6] of which certain serotypes cause illness such as salmonellosis. Most infections are due to the ingestion of food contaminated by feces. Typhoidal Salmonella serotypes can only be transferred between humans and can cause foodborne illness as well as typhoid and paratyphoid fever. Typhoid fever is caused by typhoidal Salmonella invading the bloodstream, as well as spreading throughout the body, invading organs, and secreting endotoxins (the septic form). This can lead to life-threatening hypovolemic shock and septic shock, and requires intensive care, including antibiotics.

Nontyphoidal Salmonella serotypes are zoonotic and can be transferred from animals and between humans. They usually invade only the gastrointestinal tract and cause salmonellosis, the symptoms of which can be resolved without antibiotics. However, in sub-Saharan Africa, nontyphoidal Salmonella can be invasive and cause paratyphoid fever, which requires immediate antibiotic treatment.[7]

Taxonomy

[edit]The genus Salmonella is part of the family of Enterobacteriaceae. Its taxonomy has been revised and has the potential to confuse. The genus comprises two species, S. bongori and S. enterica, the latter of which is divided into six subspecies: S. e. enterica, S. e. salamae, S. e. arizonae, S. e. diarizonae, S. e. houtenae, and S. e. indica.[8][9] The taxonomic group contains more than 2500 serotypes (also serovars) defined on the basis of the somatic O (lipopolysaccharide) and flagellar H antigens (the Kauffman–White classification). The full name of a serotype is given as, for example, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serotype Typhimurium, but can be abbreviated to Salmonella Typhimurium. Further differentiation of strains to assist clinical and epidemiological investigation may be achieved by antibiotic sensitivity testing and by other molecular biology techniques such as pulsed-field gel electrophoresis, multilocus sequence typing, and, increasingly, whole genome sequencing. Historically, salmonellae have been clinically categorized as invasive (typhoidal) or non-invasive (nontyphoidal salmonellae) based on host preference and disease manifestations in humans.[10]

History

[edit]Salmonella was first visualized in 1880 by Karl Eberth in the Peyer's patches and spleens of typhoid patients.[11] Four years later, Georg Theodor Gaffky was able to grow the pathogen in pure culture.[12] A year after that, medical research scientist Theobald Smith discovered what would be later known as Salmonella enterica (var. Choleraesuis). At the time, Smith was working as a research laboratory assistant in the Veterinary Division of the United States Department of Agriculture. The division was under the administration of Daniel Elmer Salmon, a veterinary pathologist.[13] Initially, Salmonella Choleraesuis was thought to be the causative agent of hog cholera, so Salmon and Smith named it "Hog-cholera bacillus". The name Salmonella was not used until 1900, when Joseph Leon Lignières proposed that the pathogen discovered by Salmon's group be called Salmonella in his honor.[14]: 16

In the late 1930s, Australian bacteriologist Nancy Atkinson established a salmonella typing laboratory – one of only three in the world at the time – at the Government of South Australia's Laboratory of Pathology and Bacteriology in Adelaide (later the Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science). It was here that Atkinson described multiple new strains of salmonella, including Salmonella Adelaide, which was isolated in 1943. Atkinson published her work on salmonellas in 1957.[15]

Serotyping

[edit]Serotyping is done by mixing cells with antibodies for a particular antigen. It can give some idea about risk. A 2014 study showed that S. Reading is very common among young turkey samples, but it is not a significant contributor to human salmonellosis.[16] Serotyping can assist in identifying the source of contamination by matching serotypes in people with serotypes in the suspected source of infection.[17] Appropriate prophylactic treatment can be identified from the known antibiotic resistance of the serotype.[18]

Newer methods of "serotyping" include xMAP and real-time PCR, two methods based on DNA sequences instead of antibody reactions. These methods can be potentially faster, thanks to advances in sequencing technology. These "molecular serotyping" systems actually perform genotyping of the genes that determine surface antigens.[19][20]

Detection, culture, and growth conditions

[edit]

Most subspecies of Salmonella produce hydrogen sulfide,[21] which can readily be detected by growing them on media containing ferrous sulfate, such as is used in the triple sugar iron test. Most isolates exist in two phases, a motile phase and a non-motile phase. Cultures that are nonmotile upon primary culture may be switched to the motile phase using a Craigie tube or ditch plate.[22] RVS broth can be used to enrich for Salmonella species for detection in a clinical sample.[23]

Salmonella can also be detected and subtyped using multiplex[24] or real-time polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)[25] from extracted Salmonella DNA.

Mathematical models of Salmonella growth kinetics have been developed for chicken, pork, tomatoes, and melons.[26][27][28][29][30] Salmonella reproduce asexually with a cell division interval of 40 minutes.[14][16][17][18]

Salmonella species lead predominantly host-associated lifestyles, but the bacteria were found to be able to persist in a bathroom setting for weeks following contamination, and are frequently isolated from water sources, which act as bacterial reservoirs and may help to facilitate transmission between hosts.[31] Salmonella is notorious for its ability to survive desiccation and can persist for years in dry environments and foods.[32]

The bacteria are not destroyed by freezing,[33][34] but UV light and heat accelerate their destruction. They perish after being heated to 55 °C (131 °F) for 90 min, or to 60 °C (140 °F) for 12 min,[35] although if inoculated in high fat, high liquid substances like peanut butter, they gain heat resistance and can survive up to 90 °C (194 °F) for 30 min.[36] To protect against Salmonella infection, heating food to an internal temperature of 75 °C (167 °F) is recommended.[37][38]

Salmonella species can be found in the digestive tracts of humans and animals, especially reptiles. Salmonella on the skin of reptiles or amphibians can be passed to people who handle the animals.[39] Food and water can also be contaminated with the bacteria if they come in contact with the feces of infected people or animals.[40]

Nomenclature

[edit]Initially, each Salmonella "species" was named according to clinical consideration, for example Salmonella typhi-murium (mouse-typhoid), S. cholerae-suis (pig-cholera). After host specificity was recognized not to exist for many species, new strains received species names according to the location at which the new strain was isolated.[41]

In 1987, Le Minor and Popoff used molecular findings to argue that Salmonella consisted of only one species, S. enterica, turning former "species" names into serotypes.[42] In 1989, Reeves et al. proposed that the serotype V should remain its own species, resurrecting the name S. bongori.[43] The current (by 2005) nomenclature has thus taken shape, with six recognised subspecies under S. enterica: enterica (serotype I), salamae (serotype II), arizonae (IIIa), diarizonae (IIIb), houtenae (IV), and indica (VI).[3][44][45][46] As specialists in infectious disease are not familiar with the new nomenclature, the traditional nomenclature remains common.[citation needed]

The serotype or serovar is a classification of Salmonella based on antigens that the organism presents. The Kauffman–White classification scheme differentiates serological varieties from each other. Serotypes are usually put into subspecies groups after the genus and species, with the serotypes/serovars capitalized, but not italicized: An example is Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. More modern approaches for typing and subtyping Salmonella include DNA-based methods such as pulsed field gel electrophoresis, multiple-loci VNTR analysis, multilocus sequence typing, and multiplex-PCR-based methods.[47][48]

In 2005, a third species, Salmonella subterranea, was proposed, but according to the World Health Organization, the bacterium reported does not belong in the genus Salmonella.[49] In 2016, S. subterranea was proposed to be assigned to Atlantibacter subterranea,[50] but LPSN rejects it as an invalid publication, as it was made outside of IJSB and IJSEM.[51] GTDB and NCBI agree with the 2016 reassignment.[52][53]

GTDB RS202 reports that S. arizonae, S. diarizonae, and S. houtenae should be species of their own.[54]

Pathogenicity

[edit]Salmonella species are facultative intracellular pathogens.[6] Salmonella can invade different cell types, including epithelial cells, M cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells.[55] As facultative anaerobic organism, Salmonella uses oxygen to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in aerobic environments (i.e., when oxygen is available). However, in anaerobic environments (i.e., when oxygen is not available) Salmonella produces ATP by fermentation — that is, by substituting, instead of oxygen, at least one of four electron acceptors at the end of the electron transport chain: sulfate, nitrate, sulfur, or fumarate (all of which are less efficient than oxygen).[56]

Most infections are due to ingestion of food contaminated by animal feces, or by human feces (for example, from the hands of a food-service worker at a commercial eatery). Salmonella serotypes can be divided into two main groups—typhoidal and nontyphoidal. Typhoidal serotypes include Salmonella Typhi and Salmonella Paratyphi A, which are adapted to humans and do not occur in other animals. Nontyphoidal serotypes are more common, and usually cause self-limiting gastrointestinal disease. They can infect a range of animals, and are zoonotic, meaning they can be transferred between humans and other animals.[57][citation needed]

Salmonella pathogenicity and host interaction has been studied extensively since the 2010s. Most of the important virulent genes of Salmonella are encoded in five pathogenicity islands — the so-called Salmonella pathogenicity islands (SPIs). These are chromosomal encoded and make a significant contribution to bacterial-host interaction. More traits, like plasmids, flagella or biofilm-related proteins, can contribute in the infection. SPIs are regulated by complex and fine-tuned regulatory networks that allow the gene expression only in the presence of the right environmental stresses.[58]

Molecular modeling and active site analysis of SdiA homolog, a putative quorum sensor for Salmonella typhimurium pathogenicity, reveals the specific binding patterns of AHL transcriptional regulators.[59] It is also known that Salmonella plasmid virulence gene spvB enhances bacterial virulence by inhibiting autophagy.[60]

Typhoidal Salmonella

[edit]Typhoid fever is caused by Salmonella serotypes which are strictly adapted to humans or higher primates—these include Salmonella Typhi, Paratyphi A, Paratyphi B, and Paratyphi C. In the systemic form of the disease, salmonellae pass through the lymphatic system of the intestine into the blood of the patients (typhoid form) and are carried to various organs (liver, spleen, kidneys) to form secondary foci (septic form). Endotoxins first act on the vascular and nervous apparatus, resulting in increased permeability and decreased tone of the vessels, upset of thermal regulation, and vomiting and diarrhoea. In severe forms of the disease, enough liquid and electrolytes are lost to upset the water-salt metabolism, decrease the circulating blood volume and arterial pressure, and cause hypovolemic shock. Septic shock may also develop. Shock of mixed character (with signs of both hypovolemic and septic shock) is more common in severe salmonellosis. Oliguria and azotemia may develop in severe cases as a result of renal involvement due to hypoxia and toxemia.[citation needed]

Nontyphoidal Salmonella

[edit]Non-invasive

[edit]Infection with nontyphoidal serotypes of Salmonella generally results in food poisoning. Infection usually occurs when a person ingests foods that contain a high concentration[clarification needed] of the bacteria. Infants and young children are much more susceptible to infection, easily achieved by ingesting a small number[clarification needed] of bacteria. In infants, infection through inhalation of bacteria-laden dust is possible.[citation needed]

The organisms enter through the digestive tract and must be ingested in large numbers to cause disease in healthy adults. An infection can only begin after living salmonellae (not merely Salmonella-produced toxins) reach the gastrointestinal tract. Some of the microorganisms are killed in the stomach, while the surviving ones enter the small intestine and multiply in tissues. Gastric acidity is responsible for the destruction of the majority of ingested bacteria, but Salmonella has evolved a degree of tolerance to acidic environments that allows a subset of ingested bacteria to survive.[61] Bacterial colonies may also become trapped in mucus produced in the esophagus. By the end of the incubation period, the nearby host cells are poisoned by endotoxins released from the dead salmonellae. The local response to the endotoxins is enteritis and gastrointestinal disorder.[citation needed]

About 2,000 serotypes of nontyphoidal Salmonella are known, which may be responsible for as many as 1.4 million illnesses in the United States each year. People who are at risk for severe illness include infants, elderly, organ-transplant recipients, and the immunocompromised.[40]

Invasive

[edit]While in developed countries, nontyphoidal serotypes present mostly as gastrointestinal disease, in sub-Saharan Africa, these serotypes can create a major problem in bloodstream infections, and are the most commonly isolated bacteria from the blood of those presenting with fever. Bloodstream infections caused by nontyphoidal salmonellae in Africa were reported in 2012 to have a case fatality rate of 20–25%. Most cases of invasive nontyphoidal Salmonella infection (iNTS) are caused by Salmonella enterica Typhimurium or Salmonella enterica Enteritidis. A new form of Salmonella Typhimurium (ST313) emerged in the southeast of the African continent 75 years ago, followed by a second wave which came out of central Africa 18 years later. This second wave of iNTS possibly originated in the Congo Basin, and early in the event picked up a gene that made it resistant to the antibiotic chloramphenicol. This created the need to use expensive antimicrobial drugs in areas of Africa that were very poor, making treatment difficult. The increased prevalence of iNTS in sub-Saharan Africa compared to other regions is thought to be due to the large proportion of the African population with some degree of immune suppression or impairment due to the burden of HIV, malaria, and malnutrition, especially in children. The genetic makeup of iNTS is evolving into a more typhoid-like bacterium, able to efficiently spread around the human body. Symptoms are reported to be diverse, including fever, hepatosplenomegaly, and respiratory symptoms, often with an absence of gastrointestinal symptoms.[62]

Epidemiology

[edit]Due to being considered sporadic, between 60% and 80% of salmonella infections cases go undiagnosed.[63] In March 2010, data analysis was completed to estimate an incidence rate of 1140 per 100,000 person-years. In the same analysis, 93.8 million cases of gastroenteritis were due to salmonella infections. At the 5th percentile the estimated amount was 61.8 million cases and at the 95th percentile the estimated amount was 131.6 million cases. The estimated number of deaths due to salmonella was approximately 155,000 deaths.[64] In 2014, in countries such as Bulgaria and Portugal, children under 4 were 32 and 82 times more likely, respectively, to have a salmonella infection.[65] Those who are most susceptible to infection are: children, pregnant women, elderly people, and those with deficient immune systems.[66]

Risk factors for Salmonella infections include a variety of foods. Meats such as chicken and pork have the possibility to be contaminated. A variety of vegetables and sprouts may also have salmonella. Lastly, a variety of processed foods such as chicken nuggets and pot pies may also contain this bacteria.[67]

Successful forms of prevention come from existing entities such as the FDA, United States Department of Agriculture, and the Food Safety and Inspection Service. All of these organizations create standards and inspections to ensure public safety in the U.S. For example, the FSIS agency working with the USDA has a Salmonella Action Plan in place. Recently, it received a two-year plan update in February 2016. Their accomplishments and strategies to reduce Salmonella infection are presented in the plans.[68] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also provides valuable information on preventative care, such has how to safely handle raw foods, and the correct way to store these products. In the European Union, the European Food Safety Authority created preventative measures through risk management and risk assessment. From 2005 to 2009, the EFSA placed an approach to reduce exposure to Salmonella. Their approach included risk assessment and risk management of poultry, which resulted in a reduction of infection cases by one half.[69] In Latin America an orally administered vaccine for Salmonella in poultry developed by Dr. Sherry Layton has been introduced which prevents the bacteria from contaminating the birds.[70]

A recent Salmonella Typhimurium outbreak has been linked to chocolate produced in Belgium, leading to the country halting Kinder chocolate production.[71][72]

Global monitoring

[edit]In Germany, food-borne infections must be reported.[73] From 1990 to 2016, the number of officially recorded cases decreased from about 200,000 to about 13,000 cases.[74] In the United States, about 1,200,000 cases of Salmonella infection are estimated to occur each year.[75] A World Health Organization study estimated that 21,650,974 cases of typhoid fever occurred in 2000, 216,510 of which resulted in death, along with 5,412,744 cases of paratyphoid fever.[76]

Molecular mechanisms of infection

[edit]The mechanisms of infection differ between typhoidal and nontyphoidal serotypes, owing to their different targets in the body and the different symptoms that they cause. Both groups must enter by crossing the barrier created by the intestinal cell wall, but once they have passed this barrier, they use different strategies to cause infection.[citation needed]

Switch to virulence

[edit]While travelling to their target tissue in the gastrointestinal tract, Salmonella is exposed to stomach acid, to the detergent-like activity of bile in the intestine, to decreasing oxygen supply, to the competing normal gut flora, and finally to antimicrobial peptides present on the surface of the cells lining the intestinal wall. All of these form stresses that Salmonella can sense and reacts against, and they form virulence factors and as such regulate the switch from their normal growth in the intestine into virulence.[77]

The switch to virulence gives access to a replication niche inside the host (such as humans), and can be summarised into several stages:[citation needed]

- Approach, in which they travel towards a host cell via intestinal peristalsis and through active swimming via the flagella, penetrate the mucus barrier, and locate themselves close to the epithelium lining the intestine,

- Adhesion, in which they adhere to a host cell using bacterial adhesins and a type III secretion system,

- Invasion, in which Salmonella enter the host cell (see variant mechanisms below),

- Replication, in which the bacterium may reproduce inside the host cell,

- Spread, in which the bacterium can spread to other organs via cells in the blood (if it succeeded in avoiding the immune defence). Alternatively, bacteria can go back towards the intestine, re-seeding the intestinal population.

- Re-invasion (a secondary infection, if now at a systemic site) and further replication.

Mechanisms of entry

[edit]Nontyphoidal serotypes preferentially enter M cells on the intestinal wall by bacterial-mediated endocytosis, a process associated with intestinal inflammation and diarrhoea. They are also able to disrupt tight junctions between the cells of the intestinal wall, impairing the cells' ability to stop the flow of ions, water, and immune cells into and out of the intestine. The combination of the inflammation caused by bacterial-mediated endocytosis and the disruption of tight junctions is thought to contribute significantly to the induction of diarrhoea.[78]

Salmonellae are also able to breach the intestinal barrier via phagocytosis and trafficking by CD18-positive immune cells, which may be a mechanism key to typhoidal Salmonella infection. This is thought to be a more stealthy way of passing the intestinal barrier, and may, therefore, contribute to the fact that lower numbers of typhoidal Salmonella are required for infection than nontyphoidal Salmonella.[78] Salmonella cells are able to enter macrophages via macropinocytosis.[79] Typhoidal serotypes can use this to achieve dissemination throughout the body via the mononuclear phagocyte system, a network of connective tissue that contains immune cells, and surrounds tissue associated with the immune system throughout the body.[78]

Much of the success of Salmonella in causing infection is attributed to two type III secretion systems (T3SS) which are expressed at different times during the infection. The T3SS-1 enables the injection of bacterial effectors within the host cytosol. These T3SS-1 effectors stimulate the formation of membrane ruffles allowing the uptake of Salmonella by nonphagocytic cells. Salmonella further resides within a membrane-bound compartment called the Salmonella-Containing Vacuole (SCV). The acidification of the SCV leads to the expression of the T3SS-2. The secretion of T3SS-2 effectors by Salmonella is required for its efficient survival in the host cytosol and establishment of systemic disease.[78] In addition, both T3SS are involved in the colonization of the intestine, induction of intestinal inflammatory responses and diarrhea. These systems contain many genes which must work cooperatively to achieve infection.[citation needed]

The AvrA toxin injected by the SPI1 type III secretion system of S. Typhimurium works to inhibit the innate immune system by virtue of its serine/threonine acetyltransferase activity, and requires binding to eukaryotic target cell phytic acid (IP6).[80] This leaves the host more susceptible to infection.[citation needed]

Clinical symptoms

[edit]Salmonellosis is known to be able to cause back pain or spondylosis. It can manifest as five clinical patterns: gastrointestinal tract infection, enteric fever, bacteremia, local infection, and the chronic reservoir state. The initial symptoms are nonspecific fever, weakness, and myalgia among others. In the bacteremia state, it can spread to any parts of the body and this induces localized infection or it forms abscesses. The forms of localized Salmonella infections are arthritis, urinary tract infection, infection of the central nervous system, bone infection, soft tissue infection, etc.[81] Infection may remain as the latent form for a long time, and when the function of reticular endothelial cells is deteriorated, it may become activated and consequently, it may secondarily induce spreading infection in the bone several months or several years after acute salmonellosis.[81]

A 2018 Imperial College London study also shows how salmonella disrupt specific arms of the immune system (e.g. 3 of 5 NF-kappaB proteins) using a family of zinc metalloproteinase effectors, leaving others untouched.[82] Salmonella thyroid abscess has also been reported.[83]

Resistance to oxidative burst

[edit]A hallmark of Salmonella pathogenesis is the ability of the bacterium to survive and proliferate within phagocytes. Phagocytes produce DNA-damaging agents such as nitric oxide and oxygen radicals as a defense against pathogens. Thus, Salmonella species must face attack by molecules that challenge genome integrity. Buchmeier et al.[84] showed that mutants of S. enterica lacking RecA or RecBC protein function are highly sensitive to oxidative compounds synthesized by macrophages, and furthermore these findings indicate that successful systemic infection by S. enterica requires RecA- and RecBC-mediated recombinational repair of DNA damage.[84][85]

Host adaptation

[edit]S. enterica, through some of its serotypes such as Typhimurium and Enteritidis, shows signs that it has the ability to infect several different mammalian host species, while other serotypes, such as Typhi, seem to be restricted to only a few hosts.[86] Two ways that Salmonella serotypes have adapted to their hosts are by the loss of genetic material, and mutation. In more complex mammalian species, immune systems, which include pathogen specific immune responses, target serovars of Salmonella by binding antibodies to structures such as flagella. Thus Salmonella that has lost the genetic material which codes for a flagellum to form can evade a host's immune system.[87] mgtC leader RNA from bacteria virulence gene (mgtCBR operon) decreases flagellin production during infection by directly base pairing with mRNAs of the fljB gene encoding flagellin and promotes degradation.[88] In the study by Kisela et al., more pathogenic serovars of S. enterica were found to have certain adhesins in common that have developed out of convergent evolution.[89] This means that, as these strains of Salmonella have been exposed to similar conditions such as immune systems, similar structures evolved separately to negate these similar, more advanced defenses in hosts. Although many questions remain about how Salmonella has evolved into so many different types, Salmonella may have evolved through several phases. For example, as Baumler et al. have suggested, Salmonella most likely evolved through horizontal gene transfer, and through the formation of new serovars due to additional pathogenicity islands, and through an approximation of its ancestry.[90] So, Salmonella could have evolved into its many different serotypes by gaining genetic information from different pathogenic bacteria. The presence of several pathogenicity islands in the genome of different serotypes has lent credence to this theory.[90]

Salmonella sv. Newport shows signs of adaptation to a plant-colonization lifestyle, which may play a role in its disproportionate association with food-borne illness linked to produce. A variety of functions selected for during sv. Newport persistence in tomatoes have been reported to be similar to those selected for in sv. Typhimurium from animal hosts.[91] The papA gene, which is unique to sv. Newport, contributes to the strain's fitness in tomatoes, and has homologs in the genomes of other Enterobacteriaceae that are able to colonize plant and animal hosts.[91]

Research

[edit]In addition to their importance as pathogens, nontyphoidal Salmonella species such as S. enterica serovar Typhimurium are commonly used as homologues of typhoid species. Many findings are transferable and it attenuates the danger for the researcher in case of contamination, but is also limited. For example, it is not possible to study specific typhoidal toxins using this model.[92] However, strong research tools such as the commonly-used mouse intestine gastroenteritis model build upon the use of Salmonella Typhimurium.[93]

For genetics, S. Typhimurium has been instrumental in the development of genetic tools that led to an understanding of fundamental bacterial physiology. These developments were enabled by the discovery of the first generalized transducing phage P22[94] in S. Typhimurium, that allowed quick and easy genetic editing. In turn, this made fine structure genetic analysis possible. The large number of mutants led to a revision of genetic nomenclature for bacteria.[95] Many of the uses of transposons as genetic tools, including transposon delivery, mutagenesis, and construction of chromosome rearrangements, were also developed in S. Typhimurium. These genetic tools also led to a simple test for carcinogens, the Ames test.[96]

As a natural alternative to traditional antimicrobials, phages are being recognised as highly effective control agents for Salmonella and other foodborne bacteria.[97]

Ancient DNA

[edit]S. enterica genomes have been reconstructed from up to 6,500 year old human remains across Western Eurasia, which provides evidence for geographic widespread infections with systemic S. enterica during prehistory, and a possible role of the Neolithization process in the evolution of host adaptation.[98][99] Additional reconstructed genomes from colonial Mexico suggest S. enterica as the cause of cocoliztli, an epidemic in 16th-century New Spain.[100]

See also

[edit]- 1984 Rajneeshee bioterror attack

- 2008 United States salmonellosis outbreak

- American Public Health Association v. Butz

- Bismuth sulfite agar

- Food testing strips

- Host–pathogen interaction

- List of foodborne illness outbreaks

- 2008–2009 peanut-borne salmonellosis

- Wright County Egg

- XLD agar

References

[edit]- ^ "Salmonella". NCBI taxonomy. Bethesda, MD: National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Su LH, Chiu CH (2007). "Salmonella: clinical importance and evolution of nomenclature". Chang Gung Medical Journal. 30 (3): 210–219. PMID 17760271.

- ^ a b Ryan MP, O'Dwyer J, Adley CC (2017). "Evaluation of the Complex Nomenclature of the Clinically and Veterinary Significant Pathogen Salmonella". BioMed Research International. 2017: 3782182. doi:10.1155/2017/3782182. PMC 5429938. PMID 28540296.

- ^ Gal-Mor O, Boyle EC, Grassl GA (2014). "Same species, different diseases: how and why typhoidal and non-typhoidal Salmonella enterica serovars differ". Frontiers in Microbiology. 5: 391. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2014.00391. PMC 4120697. PMID 25136336.

- ^ a b Fàbrega A, Vila J (April 2013). "Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium skills to succeed in the host: virulence and regulation". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 26 (2): 308–341. doi:10.1128/CMR.00066-12. PMC 3623383. PMID 23554419.

- ^ a b Jantsch J, Chikkaballi D, Hensel M (March 2011). "Cellular aspects of immunity to intracellular Salmonella enterica". Immunological Reviews. 240 (1): 185–195. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2010.00981.x. PMID 21349094. S2CID 19344119.

- ^ Ryan I KJ, Ray CG, eds. (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). McGraw Hill. pp. 362–8. ISBN 978-0-8385-8529-0.

- ^ Brenner FW, Villar RG, Angulo FJ, Tauxe R, Swaminathan B (July 2000). "Salmonella nomenclature". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 38 (7): 2465–2467. doi:10.1128/JCM.38.7.2465-2467.2000. PMC 86943. PMID 10878026.

- ^ Gillespie, Stephen H., Hawkey, Peter M., eds. (2006). Principles and practice of clinical bacteriology (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-01796-8.

- ^ Okoro CK, Kingsley RA, Connor TR, Harris SR, Parry CM, Al-Mashhadani MN, Kariuki S, Msefula CL, Gordon MA, de Pinna E, Wain J, Heyderman RS, Obaro S, Alonso PL, Mandomando I, MacLennan CA, Tapia MD, Levine MM, Tennant SM, Parkhill J, Dougan G (November 2012). "Intracontinental spread of human invasive Salmonella Typhimurium pathovariants in sub-Saharan Africa". Nature Genetics. 44 (11): 1215–1221. doi:10.1038/ng.2423. PMC 3491877. PMID 23023330.

- ^ Eberth CJ (1880-07-01). "Die Organismen in den Organen bei Typhus abdominalis". Archiv für Pathologische Anatomie und Physiologie und für Klinische Medicin (in German). 81 (1): 58–74. doi:10.1007/BF01995472. S2CID 6979333.

- ^ Hardy A (August 1999). "Food, hygiene, and the laboratory. A short history of food poisoning in Britain, circa 1850-1950". Social History of Medicine. 12 (2): 293–311. doi:10.1093/shm/12.2.293. PMID 11623930.

- ^ "FDA/CFSAN—Food Safety A to Z Reference Guide—Salmonella". FDA–Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. 2008-07-03. Archived from the original on 2009-03-02. Retrieved 2009-02-14.

- ^ a b Heymann DA, Alcamo IE, Heymann DL (2006). Salmonella. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7910-8500-4. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ McEwin E. "Atkinson, Nancy (1910–1999)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. ISSN 1833-7538. OCLC 70677943. Retrieved 2022-10-27.

- ^ a b "Serotypes Profile of Salmonella Isolates from Meat and Poultry Products, January 1998 through December 2014" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Steps in a Foodborne Outbreak Investigation". 2018-11-09.

- ^ a b Yoon KB, Song BJ, Shin MY, Lim HC, Yoon YH, Jeon DY, Ha H, Yang SI, Kim JB (June 2017). "Antibiotic Resistance Patterns and Serotypes of Salmonella spp. Isolated at Jeollanam-do in Korea". Osong Public Health and Research Perspectives. 8 (3): 211–219. doi:10.24171/j.phrp.2017.8.3.08. PMC 5525558. PMID 28781944.

- ^ Luo Y, Huang C, Ye J, Octavia S, Wang H, Dunbar SA, Jin D, Tang YW, Lan R (2020-09-07). "Comparison of xMAP Salmonella Serotyping Assay With Traditional Serotyping and Discordance Resolution by Whole Genome Sequencing". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 10: 452. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2020.00452. PMC 7504902. PMID 33014887.

- ^ Nair S, Patel V, Hickey T, Maguire C, Greig DR, Lee W, Godbole G, Grant K, Chattaway MA (August 2019). Ledeboer NA (ed.). "Real-Time PCR Assay for Differentiation of Typhoidal and Nontyphoidal Salmonella". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 57 (8): e00167–19. doi:10.1128/JCM.00167-19. PMC 6663909. PMID 31167843.

- ^ Clark MA, Barrett EL (June 1987). "The phs gene and hydrogen sulfide production by Salmonella typhimurium". Journal of Bacteriology. 169 (6): 2391–2397. doi:10.1128/jb.169.6.2391-2397.1987. PMC 212072. PMID 3108233.

- ^ "UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations: Changing the Phase of Salmonella" (PDF). UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations: 8–10. 8 January 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- ^ Snyder JW, Atlas RM (2006). Handbook of Media for Clinical Microbiology. CRC Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-8493-3795-6.

- ^ Alvarez J, Sota M, Vivanco AB, Perales I, Cisterna R, Rementeria A, Garaizar J (April 2004). "Development of a multiplex PCR technique for detection and epidemiological typing of salmonella in human clinical samples". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 42 (4): 1734–1738. doi:10.1128/JCM.42.4.1734-1738.2004. PMC 387595. PMID 15071035.

- ^ Hoorfar J, Ahrens P, Rådström P (September 2000). "Automated 5' nuclease PCR assay for identification of Salmonella enterica". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 38 (9): 3429–3435. doi:10.1128/JCM.38.9.3429-3435.2000. PMC 87399. PMID 10970396.

- ^ Dominguez SA, Schaffner DW (December 2008). "Modeling the growth of Salmonella in raw poultry stored under aerobic conditions". Journal of Food Protection. 71 (12): 2429–2435. doi:10.4315/0362-028x-71.12.2429. PMID 19244895.

- ^ Pin C, Avendaño-Perez G, Cosciani-Cunico E, Gómez N, Gounadakic A, Nychas GJ, Skandamis P, Barker G (March 2011). "Modelling Salmonella concentration throughout the pork supply chain by considering growth and survival in fluctuating conditions of temperature, pH and a(w)". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 145 (Suppl 1): S96-102. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.09.025. PMID 20951457.

- ^ Pan W, Schaffner DW (August 2010). "Modeling the growth of Salmonella in cut red round tomatoes as a function of temperature". Journal of Food Protection. 73 (8): 1502–1505. doi:10.4315/0362-028X-73.8.1502. PMID 20819361.

- ^ Li D, Friedrich LM, Danyluk MD, Harris LJ, Schaffner DW (June 2013). "Development and validation of a mathematical model for growth of pathogens in cut melons". Journal of Food Protection. 76 (6): 953–958. doi:10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-398. PMID 23726189.

- ^ Li D. "Development and validation of a mathematical model for growth of salmonella in cantaloupe". Archived from the original on November 20, 2013.

- ^ Winfield MD, Groisman EA (July 2003). "Role of nonhost environments in the lifestyles of Salmonella and Escherichia coli". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 69 (7): 3687–3694. Bibcode:2003ApEnM..69.3687W. doi:10.1128/aem.69.7.3687-3694.2003. PMC 165204. PMID 12839733.

- ^ Mandal RK, Kwon YM (8 September 2017). "Global Screening of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Genes for Desiccation Survival". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8 (1723): 1723. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01723. PMC 5596212. PMID 28943871.

- ^ Sorrells KM, Speck ML, Warren JA (January 1970). "Pathogenicity of Salmonella gallinarum after metabolic injury by freezing". Applied Microbiology. 19 (1): 39–43. doi:10.1128/AEM.19.1.39-43.1970. PMC 376605. PMID 5461164.

Mortality differences between wholly uninjured and predominantly injured populations were small and consistent (5% level) with a hypothesis of no difference.

- ^ Beuchat LR, Heaton EK (June 1975). "Salmonella survival on pecans as influenced by processing and storage conditions". Applied Microbiology. 29 (6): 795–801. doi:10.1128/AEM.29.6.795-801.1975. PMC 187082. PMID 1098573.

Little decrease in viable population of the three species was noted on inoculated pecan halves stored at -18, -7, and 5°C for 32 weeks.

- ^ Goodfellow SJ, Brown WL (August 1978). "Fate of Salmonella Inoculated into Beef for Cooking". Journal of Food Protection. 41 (8): 598–605. doi:10.4315/0362-028x-41.8.598. PMID 30795117.

- ^ Ma L, Zhang G, Gerner-Smidt P, Mantripragada V, Ezeoke I, Doyle MP (August 2009). "Thermal inactivation of Salmonella in peanut butter". Journal of Food Protection. 72 (8): 1596–1601. doi:10.4315/0362-028x-72.8.1596. PMID 19722389.

- ^ Partnership for Food Safety Education (PFSE) Fight BAC! Basic Brochure Archived 2013-08-31 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ USDA Internal Cooking Temperatures Chart Archived 2012-05-03 at the Wayback Machine. The USDA has other resources available at their Safe Food Handling Archived 2013-06-05 at the Wayback Machine fact-sheet page. See also the National Center for Home Food Preservation.

- ^ "Reptiles, Amphibians, and Salmonella". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. 25 November 2013. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- ^ a b Goldrick BA (March 2003). "Foodborne diseases". The American Journal of Nursing. 103 (3): 105–106. doi:10.1097/00000446-200303000-00043. PMID 12635640.

- ^ Kauffmann F (1941). Die Bakteriologie der Salmonella-Gruppe. Kopenhagen: Munksgaard. OCLC 3198699.

- ^ Le Minor L, Popoff MY (1987). "Request for an Opinion: Designation of Salmonella enterica sp. nov., nom. rev., as the type and only species of the genus Salmonella". Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 37 (4): 465–468. doi:10.1099/00207713-37-4-465.

- ^ Reeves MW, Evins GM, Heiba AA, Plikaytis BD, Farmer JJ (February 1989). "Clonal nature of Salmonella typhi and its genetic relatedness to other salmonellae as shown by multilocus enzyme electrophoresis, and proposal of Salmonella bongori comb. nov". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 27 (2): 313–320. doi:10.1128/JCM.27.2.313-320.1989. PMC 267299. PMID 2915026.

- ^ Janda JM, Abbott SL (2006). "The Enterobacteria", ASM Press.

- ^ Judicial Commission Of The International Committee On Systematics Of Prokaryotes (January 2005). "The type species of the genus Salmonella Lignieres 1900 is Salmonella enterica (ex Kauffmann and Edwards 1952) Le Minor and Popoff 1987, with the type strain LT2T, and conservation of the epithet enterica in Salmonella enterica over all earlier epithets that may be applied to this species. Opinion 80". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 55 (Pt 1): 519–520. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.63579-0. PMID 15653929.

- ^ Tindall BJ, Grimont PA, Garrity GM, Euzéby JP (January 2005). "Nomenclature and taxonomy of the genus Salmonella". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 55 (Pt 1): 521–524. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.63580-0. PMID 15653930.

- ^ Porwollik S, ed. (2011). Salmonella: From Genome to Function. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-73-8.

- ^ Achtman M, Wain J, Weill FX, Nair S, Zhou Z, Sangal V, Krauland MG, Hale JL, Harbottle H, Uesbeck A, Dougan G, Harrison LH, Brisse S (2012). "Multilocus sequence typing as a replacement for serotyping in Salmonella enterica". PLOS Pathogens. 8 (6): e1002776. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002776. PMC 3380943. PMID 22737074.

- ^ Grimont PA, Xavier Weill F (2007). Antigenic Formulae of the Salmonella Serovars (PDF) (9th ed.). Institut Pasteur, Paris, France: WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Salmonella. p. 7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09. Retrieved 26 August 2015.

- ^ Hata H, Natori T, Mizuno T, Kanazawa I, Eldesouky I, Hayashi M, Miyata M, Fukunaga H, Ohji S, Hosoyama A, Aono E, Yamazoe A, Tsuchikane K, Fujita N, Ezaki T (May 2016). "Phylogenetics of family Enterobacteriaceae and proposal to reclassify Escherichia hermannii and Salmonella subterranea as Atlantibacter hermannii and Atlantibacter subterranea gen. nov., comb. nov". Microbiology and Immunology. 60 (5): 303–311. doi:10.1111/1348-0421.12374. PMID 26970508. S2CID 32594451.

- ^ "Species: Atlantibacter subterranea". lpsn.dsmz.de.

- ^ "GTDB - Tree at g__Atlantibacter". gtdb.ecogenomic.org.

- ^ "Taxonomy browser (Atlantibacter)". www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ "GTDB - Tree at g__Salmonella". gtdb.ecogenomic.org.

- ^ LaRock DL, Chaudhary A, Miller SI (April 2015). "Salmonellae interactions with host processes". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 13 (4): 191–205. doi:10.1038/nrmicro3420. PMC 5074537. PMID 25749450.

- ^ Garai P, Gnanadhas DP, Chakravortty D (July 2012). "Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium and Typhi as model organisms: revealing paradigm of host–pathogen interactions". Virulence. 3 (4): 377–388. doi:10.4161/viru.21087. PMC 3478240. PMID 22722237.

- ^ "What is the difference between nontyphoidal salmonellae and S typhi or S paratyphi?". www.medscape.com. Retrieved 2021-09-28.

- ^ Fàbrega A, Vila J (April 2013). "Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium skills to succeed in the host: virulence and regulation". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 26 (2): 308–341. doi:10.1128/CMR.00066-12. PMC 3623383. PMID 23554419.

- ^ Gnanendra S, Anusuya S, Natarajan J (October 2012). "Molecular modeling and active site analysis of SdiA homolog, a putative quorum sensor for Salmonella typhimurium pathogenecity reveals specific binding patterns of AHL transcriptional regulators". Journal of Molecular Modeling. 18 (10): 4709–4719. doi:10.1007/s00894-012-1469-1. PMID 22660944. S2CID 25177221.

- ^ Li YY, Wang T, Gao S, Xu GM, Niu H, Huang R, Wu SY (February 2016). "Salmonella plasmid virulence gene spvB enhances bacterial virulence by inhibiting autophagy in a zebrafish infection model". Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 49: 252–259. doi:10.1016/j.fsi.2015.12.033. PMID 26723267.

- ^ Garcia-del Portillo F, Foster JW, Finlay BB (October 1993). "Role of acid tolerance response genes in Salmonella typhimurium virulence". Infection and Immunity. 61 (10): 4489–4492. doi:10.1128/IAI.61.10.4489-4492.1993. PMC 281185. PMID 8406841.

- ^ Feasey NA, Dougan G, Kingsley RA, Heyderman RS, Gordon MA (June 2012). "Invasive non-typhoidal salmonella disease: an emerging and neglected tropical disease in Africa". Lancet. 379 (9835): 2489–2499. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61752-2. PMC 3402672. PMID 22587967.

- ^ "Salmonella (non-typhoidal)". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- ^ Majowicz SE, Musto J, Scallan E, Angulo FJ, Kirk M, O'Brien SJ, Jones TF, Fazil A, Hoekstra RM (March 2010). "The global burden of nontyphoidal Salmonella gastroenteritis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 50 (6): 882–889. doi:10.1086/650733. PMID 20158401.

- ^ "Salmonellosis - Annual Epidemiological Report 2016 [2014 data]". European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 2016-01-31. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- ^ "Get the Facts about Salmonella!". Center for Veterinary Medicine, FDA. 2019-06-06.

- ^ "Prevention | General Information | Salmonella | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2019-03-06. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- ^ "Salmonella". fsis.usda.gov.

- ^ "Salmonella". European Food Safety Authority. Retrieved 2019-12-05.

- ^ "Content not found". 3 March 2022.

- ^ Samarasekera U (July 2022). "Salmonella Typhimurium outbreak linked to chocolate". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 22 (7): 947. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00351-6. PMID 35636448. S2CID 249136373.

- ^ "Kinder recall: ECDC urges further investigation at Belgian plant". euronews. 2022-04-15. Retrieved 2024-09-27.

- ^ § 6 and § 7 of the German law on infectious disease prevention, Infektionsschutzgesetz

- ^ "Anzahl der jährlich registrierten Salmonellose-Erkrankungen in Deutschland bis 2016". Statista.

- ^ Salmonella. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- ^ Crump JA, Luby SP, Mintz ED (May 2004). "The global burden of typhoid fever". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 82 (5): 346–353. PMC 2622843. PMID 15298225.

- ^ Rychlik I, Barrow PA (November 2005). "Salmonella stress management and its relevance to behaviour during intestinal colonisation and infection". FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 29 (5): 1021–1040. doi:10.1016/j.femsre.2005.03.005. PMID 16023758.

- ^ a b c d Haraga A, Ohlson MB, Miller SI (January 2008). "Salmonellae interplay with host cells". Nature Reviews. Microbiology. 6 (1): 53–66. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1788. PMID 18026123. S2CID 2365666.

- ^ Kerr MC, Wang JT, Castro NA, Hamilton NA, Town L, Brown DL, Meunier FA, Brown NF, Stow JL, Teasdale RD (April 2010). "Inhibition of the PtdIns(5) kinase PIKfyve disrupts intracellular replication of Salmonella". The EMBO Journal. 29 (8): 1331–1347. doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.28. PMC 2868569. PMID 20300065.

- ^ Mittal R, Peak-Chew SY, Sade RS, Vallis Y, McMahon HT (June 2010). "The acetyltransferase activity of the bacterial toxin YopJ of Yersinia is activated by eukaryotic host cell inositol hexakisphosphate". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (26): 19927–19934. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.126581. PMC 2888404. PMID 20430892.

- ^ a b Choi YS, Cho WJ, Yun SH, Lee SY, Park SH, Park JC, Jang EH, Shin HY (December 2010). "A case of back pain caused by Salmonella spondylitis -A case report-". Korean Journal of Anesthesiology. 59 (Suppl): S233 – S237. doi:10.4097/kjae.2010.59.S.S233. PMC 3030045. PMID 21286449.

- ^ "Bacterial protein mimics DNA to sabotage cells' defenses: Study reveals details of Salmonella infections". Sciencedaily.

- ^ Sahli M, Hemmaoui B, Errami N, Benariba F (January 2022). "Salmonella thyroid abscess". European Annals of Otorhinolaryngology, Head and Neck Diseases. 139 (1): 51–52. doi:10.1016/j.anorl.2021.05.004. PMID 34053890. S2CID 235256840.

- ^ a b Buchmeier NA, Lipps CJ, So MY, Heffron F (March 1993). "Recombination-deficient mutants of Salmonella typhimurium are avirulent and sensitive to the oxidative burst of macrophages". Molecular Microbiology. 7 (6): 933–936. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01184.x. PMID 8387147. S2CID 25127127.

- ^ Cano DA, Pucciarelli MG, García-del Portillo F, Casadesús J (January 2002). "Role of the RecBCD recombination pathway in Salmonella virulence". Journal of Bacteriology. 184 (2): 592–595. doi:10.1128/jb.184.2.592-595.2002. PMC 139588. PMID 11751841.

- ^ Thomson NR, Clayton DJ, Windhorst D, Vernikos G, Davidson S, Churcher C, Quail MA, Stevens M, Jones MA, Watson M, Barron A, Layton A, Pickard D, Kingsley RA, Bignell A, Clark L, Harris B, Ormond D, Abdellah Z, Brooks K, Cherevach I, Chillingworth T, Woodward J, Norberczak H, Lord A, Arrowsmith C, Jagels K, Moule S, Mungall K, Sanders M, Whitehead S, Chabalgoity JA, Maskell D, Humphrey T, Roberts M, Barrow PA, Dougan G, Parkhill J (October 2008). "Comparative genome analysis of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 and Salmonella Gallinarum 287/91 provides insights into evolutionary and host adaptation pathways". Genome Research. 18 (10): 1624–1637. doi:10.1101/gr.077404.108. PMC 2556274. PMID 18583645.

- ^ den Bakker HC, Moreno Switt AI, Govoni G, Cummings CA, Ranieri ML, Degoricija L, Hoelzer K, Rodriguez-Rivera LD, Brown S, Bolchacova E, Furtado MR, Wiedmann M (August 2011). "Genome sequencing reveals diversification of virulence factor content and possible host adaptation in distinct subpopulations of Salmonella enterica". BMC Genomics. 12: 425. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-425. PMC 3176500. PMID 21859443.

- ^ Choi E, Han Y, Cho YJ, Nam D, Lee EJ (September 2017). "A trans-acting leader RNA from a Salmonella virulence gene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (38): 10232–10237. Bibcode:2017PNAS..11410232C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1705437114. PMC 5617274. PMID 28874555.

- ^ Kisiela DI, Chattopadhyay S, Libby SJ, Karlinsey JE, Fang FC, Tchesnokova V, Kramer JJ, Beskhlebnaya V, Samadpour M, Grzymajlo K, Ugorski M, Lankau EW, Mackie RI, Clegg S, Sokurenko EV (2012). "Evolution of Salmonella enterica virulence via point mutations in the fimbrial adhesin". PLOS Pathogens. 8 (6): e1002733. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002733. PMC 3369946. PMID 22685400.

- ^ a b Bäumler AJ, Tsolis RM, Ficht TA, Adams LG (October 1998). "Evolution of host adaptation in Salmonella enterica". Infection and Immunity. 66 (10): 4579–4587. doi:10.1128/IAI.66.10.4579-4587.1998. PMC 108564. PMID 9746553.

- ^ a b de Moraes MH, Soto EB, Salas González I, Desai P, Chu W, Porwollik S, McClelland M, Teplitski M (2018). "Genome-Wide Comparative Functional Analyses Reveal Adaptations of Salmonella sv. Newport to a Plant Colonization Lifestyle". Frontiers in Microbiology. 9: 877. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00877. PMC 5968271. PMID 29867794.

- ^ Johnson R, Mylona E, Frankel G (September 2018). "Typhoidal Salmonella: Distinctive virulence factors and pathogenesis". Cellular Microbiology. 20 (9): e12939. doi:10.1111/cmi.12939. PMID 30030897. S2CID 51705854.

- ^ Hapfelmeier S, Hardt WD (October 2005). "A mouse model for S. typhimurium-induced enterocolitis". Trends in Microbiology. 13 (10): 497–503. doi:10.1016/j.tim.2005.08.008. PMID 16140013.

- ^ Zinder ND, Lederberg J (November 1952). "Genetic exchange in Salmonella". Journal of Bacteriology. 64 (5): 679–699. doi:10.1128/JB.64.5.679-699.1952. PMC 169409. PMID 12999698.

- ^ Demerec M, Adelberg EA, Clark AJ, Hartman PE (July 1966). "A proposal for a uniform nomenclature in bacterial genetics". Genetics. 54 (1): 61–76. doi:10.1093/genetics/54.1.61. PMC 1211113. PMID 5961488.

- ^ Ames BN, Mccann J, Yamasaki E (December 1975). "Methods for detecting carcinogens and mutagens with the Salmonella/mammalian-microsome mutagenicity test". Mutation Research. 31 (6): 347–364. doi:10.1016/0165-1161(75)90046-1. PMID 768755.

- ^ Ge H, Lin C, Xu Y, Hu M, Xu Z, Geng S, Jiao X, Chen X (June 2022). "A phage for the controlling of Salmonella in poultry and reducing biofilms". Veterinary Microbiology. 269: 109432. doi:10.1016/j.vetmic.2022.109432. PMID 35489296. S2CID 248195843.

- ^ Key FM, Posth C, Esquivel-Gomez LR, Hübler R, Spyrou MA, Neumann GU, Furtwängler A, Sabin S, Burri M, Wissgott A, Lankapalli AK, Vågene ÅJ, Meyer M, Nagel S, Tukhbatova R, Khokhlov A, Chizhevsky A, Hansen S, Belinsky AB, Kalmykov A, Kantorovich AR, Maslov VE, Stockhammer PW, Vai S, Zavattaro M, Riga A, Caramelli D, Skeates R, Beckett J, Gradoli MG, Steuri N, Hafner A, Ramstein M, Siebke I, Lösch S, Erdal YS, Alikhan NF, Zhou Z, Achtman M, Bos K, Reinhold S, Haak W, Kühnert D, Herbig A, Krause J (March 2020). "Emergence of human-adapted Salmonella enterica is linked to the Neolithization process". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 4 (3): 324–333. Bibcode:2020NatEE...4..324K. doi:10.1038/s41559-020-1106-9. PMC 7186082. PMID 32094538.

- ^ Zhou Z, Lundstrøm I, Tran-Dien A, Duchêne S, Alikhan NF, Sergeant MJ, Langridge G, Fotakis AK, Nair S, Stenøien HK, Hamre SS, Casjens S, Christophersen A, Quince C, Thomson NR, Weill FX, Ho SY, Gilbert MT, Achtman M (August 2018). "Pan-genome Analysis of Ancient and Modern Salmonella enterica Demonstrates Genomic Stability of the Invasive Para C Lineage for Millennia". Current Biology. 28 (15): 2420–2428.e10. Bibcode:2018CBio...28E2420Z. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.05.058. PMC 6089836. PMID 30033331.

- ^ Vågene ÅJ, Herbig A, Campana MG, Robles García NM, Warinner C, Sabin S, Spyrou MA, Andrades Valtueña A, Huson D, Tuross N, Bos KI, Krause J (March 2018). "Salmonella enterica genomes from victims of a major sixteenth-century epidemic in Mexico". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2 (3): 520–528. Bibcode:2018NatEE...2..520V. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0446-6. PMID 29335577. S2CID 3358440.

External links

[edit]- Background on Salmonella from the Food Safety and Inspection Service of the United States Department of Agriculture

- Salmonella genomes and related information at PATRIC, a Bioinformatics Resource Center funded by NIAID

- Questions and Answers about commercial and institutional sanitizing methods Archived 2017-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Salmonella as an emerging pathogen from IFAS

- Notes on Salmonella nomenclature

- Salmonella motility video

- Avian Salmonella Archived 2011-12-09 at the Wayback Machine

- Overview of Salmonellosis — The Merck Veterinary Manual