Saint Nicholas: Difference between revisions

Copyedit. adding persondata using User:Dr pda/persondata.js |

NICKMELONMAN (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 34: | Line 34: | ||

{{Fix bunching|end}} |

{{Fix bunching|end}} |

||

'''Saint Nikolaos''' ({{lang-el|Άγιος Νικόλαος }}, ''Agios'' ["saint"] ''Nikolaos'' ["victory of the people"]) (270 – 6 December 346) is the canonical and most popular name for ''' |

'''Saint Nikolaos''' ({{lang-el|Άγιος Νικόλαος }}, ''Agios'' ["saint"] ''Nikolaos'' ["victory of the people"]) (270 – 6 December 346) is the canonical and most popular name for '''Saint Nick of Myra''', a [[saint]] and [[Greeks|Greek]]<ref>{{cite book |author= Cunningham, Lawrence |title=A brief history of saints |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |year=2005 |page=33 |isbn=978-1-4051-1402-8 |quote= The fourth-century Saint Nikolaos of Myra (in present-day Turkey) spread to the West through the port city of Bari in southern Italy…Devotion to the saint in the Low countries became blended with Nordic folktales, transforming this early Greek bishop into that Christmas icon, Santa Claus’. }}</ref> [[Bishop]] of [[Myra]] ([[Demre]], in [[Lycia]], part of modern-day [[Turkey]]). Because of the many [[miracle]]s attributed to his [[intercession]], he is also known as '''Nikolaos the Wonderworker''' (in Greek: thaumaturgos). He had a reputation for secret gift-giving, such as putting coins in the shoes of those who left them out for him, and thus became the model for '''[[Santa Claus]]''', whose English name comes from the Dutch [[Sinterklaas]]. His reputation evolved among the faithful, as is common for early Christian saints.<ref>Charles W. Jones, "Saint Nikolaos of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend" (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 1978.</ref> In 1087, his [[relic]]s were furtively [[Translation (relics)|translated]] to [[Bari]], in southeastern Italy; for this reason, he is also known as '''Nikolaos of Bari'''. |

||

The historical Saint Nikolaos is remembered and revered among [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] and [[Eastern Orthodoxy|Orthodox]] Christians. He is also honored by various [[Anglican]] and [[Lutheran]] churches. Saint Nicholas is the [[patron saint]] of [[sailors]], merchants, [[archery|archers]], thieves, and children, and students in Greece, Belgium, [[Romania]], [[Bulgaria]], [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]], [[Albania]], [[Russia]], the [[Republic of Macedonia]], [[Slovakia]], [[Serbia]] and [[Montenegro]]. He is also the patron saint of [[Aberdeen]], [[Amsterdam]], [[Barranquilla]], [[Bari]], [[Beit Jala]], [[Huguenots]], [[Liverpool]] and [[Siggiewi]]. In 1809, the [[New-York Historical Society]] convened and retroactively named ''Santa Claus'' the patron saint of [[New Amsterdam|Nieuw Amsterdam]], the historical name for New York City.<ref>John Steele Gordon, ''The Great Game: The Emergence of Wall Street as a World Power: 1653–2000'' (Scribner) 1999.</ref> He was also a patron of the [[Varangian]] Guard of the [[Byzantine emperors]], who protected his relics in Bari. |

The historical Saint Nikolaos is remembered and revered among [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] and [[Eastern Orthodoxy|Orthodox]] Christians. He is also honored by various [[Anglican]] and [[Lutheran]] churches. Saint Nicholas is the [[patron saint]] of [[sailors]], merchants, [[archery|archers]], thieves, and children, and students in Greece, Belgium, [[Romania]], [[Bulgaria]], [[Georgia (country)|Georgia]], [[Albania]], [[Russia]], the [[Republic of Macedonia]], [[Slovakia]], [[Serbia]] and [[Montenegro]]. He is also the patron saint of [[Aberdeen]], [[Amsterdam]], [[Barranquilla]], [[Bari]], [[Beit Jala]], [[Huguenots]], [[Liverpool]] and [[Siggiewi]]. In 1809, the [[New-York Historical Society]] convened and retroactively named ''Santa Claus'' the patron saint of [[New Amsterdam|Nieuw Amsterdam]], the historical name for New York City.<ref>John Steele Gordon, ''The Great Game: The Emergence of Wall Street as a World Power: 1653–2000'' (Scribner) 1999.</ref> He was also a patron of the [[Varangian]] Guard of the [[Byzantine emperors]], who protected his relics in Bari. |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

On 26 August 1071 [[Romanus IV]], Emperor of the [[Eastern Roman Empire]] (reigned 1068–1071), faced Sultan [[Alp Arslan]] of the [[Seljuk Turks]] (reigned 1059–1072) in the [[Battle of Manzikert]]. The battle ended in humiliating defeat and capture for Romanus. As a result the Empire temporarily lost control over most of [[Asia Minor]] to the invading [[Seljuk Turks]]. The Byzantines would regain its control over [[Asia Minor]] during the reign of [[Alexius I Comnenus]] (reigned 1081–1118). But early in his reign Myra was overtaken by the Islamic invaders. Taking advantage of the confusion, sailors from [[Bari]] in [[Apulia]] seized the remains of the saint over the objections of the Orthodox [[monasticism|monks]]. Returning to Bari, they brought the remains with them and cared for them. The remains arrived on 9 May 1087. There are numerous variations of this account. In some versions those taking the relics are characterized as thieves or pirates, in others they are said to have taken them in response to a [[Vision (religion)|vision]] wherein Saint Nicholas himself appeared and commanded that his relics be moved in order to preserve them from the impending Muslim conquest. |

On 26 August 1071 [[Romanus IV]], Emperor of the [[Eastern Roman Empire]] (reigned 1068–1071), faced Sultan [[Alp Arslan]] of the [[Seljuk Turks]] (reigned 1059–1072) in the [[Battle of Manzikert]]. The battle ended in humiliating defeat and capture for Romanus. As a result the Empire temporarily lost control over most of [[Asia Minor]] to the invading [[Seljuk Turks]]. The Byzantines would regain its control over [[Asia Minor]] during the reign of [[Alexius I Comnenus]] (reigned 1081–1118). But early in his reign Myra was overtaken by the Islamic invaders. Taking advantage of the confusion, sailors from [[Bari]] in [[Apulia]] seized the remains of the saint over the objections of the Orthodox [[monasticism|monks]]. Returning to Bari, they brought the remains with them and cared for them. The remains arrived on 9 May 1087. There are numerous variations of this account. In some versions those taking the relics are characterized as thieves or pirates, in others they are said to have taken them in response to a [[Vision (religion)|vision]] wherein Saint Nicholas himself appeared and commanded that his relics be moved in order to preserve them from the impending Muslim conquest. |

||

Some observers have reported seeing [[myrrh]] exude his relics, [[anointing]] with which has been credited with numerous [[miracle]]s. Vials of myrrh from his relics have been taken all over the world for centuries, and can still be obtained from his church in Bari. Currently at Bari, there are two churches at his shrine, one Roman Catholic and one Orthodox. |

Some observers have reported seeing [[myrrh]] exude his relics, and his fetish for monkeys. [[anointing]] with which has been credited with numerous [[miracle]]s. Vials of myrrh from his relics have been taken all over the world for centuries, and can still be obtained from his church in Bari. Currently at Bari, there are two churches at his shrine, one Roman Catholic and one Orthodox. |

||

According to a local legend, some of his remains were brought by three [[pilgrim]]s to a church in what is now [[Nikolausberg]] in the vicinity of the city of [[Göttingen]], Germany, giving the church and village its name. |

According to a local legend, some of his remains were brought by three [[pilgrim]]s to a church in what is now [[Nikolausberg]] in the vicinity of the city of [[Göttingen]], Germany, giving the church and village its name. |

||

Revision as of 01:08, 29 September 2010

Saint Nikolaos | |

|---|---|

| |

| Bishop of Myra, Defender of Orthodoxy, Wonderworker, Holy Hierarch | |

| Born | c. 270 A.D. (the Ides of March)[1] Patara, Lycia, Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) |

| Died | 6 December 347 A.D. Myra, Lycia |

| Venerated in | All Christianity |

| Canonized | Pre-Congregation |

| Major shrine | Basilica di San Nicola, Bari, Italy. |

| Feast | 6 December (main feast day) 19 December (some Eastern churches)[2] 9 May (translation of relics) |

| Attributes | Vested as a Bishop. In Eastern Christianity, wearing an omophorion and holding a Gospel Book. Sometimes shown with Jesus Christ over one shoulder, holding a Gospel Book, and with the Theotokos over the other shoulder, holding an omophorion. |

| Patronage | Children, sailors, fishermen, merchants, the falsely accused, prostitutes, repentant thieves, pharmacists, archers, pawnbrokers |

Template:Fix bunching Template:Fix bunching

Template:Fix bunching Template:Fix bunching

Saint Nikolaos (Template:Lang-el, Agios ["saint"] Nikolaos ["victory of the people"]) (270 – 6 December 346) is the canonical and most popular name for Saint Nick of Myra, a saint and Greek[3] Bishop of Myra (Demre, in Lycia, part of modern-day Turkey). Because of the many miracles attributed to his intercession, he is also known as Nikolaos the Wonderworker (in Greek: thaumaturgos). He had a reputation for secret gift-giving, such as putting coins in the shoes of those who left them out for him, and thus became the model for Santa Claus, whose English name comes from the Dutch Sinterklaas. His reputation evolved among the faithful, as is common for early Christian saints.[4] In 1087, his relics were furtively translated to Bari, in southeastern Italy; for this reason, he is also known as Nikolaos of Bari.

The historical Saint Nikolaos is remembered and revered among Catholic and Orthodox Christians. He is also honored by various Anglican and Lutheran churches. Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of sailors, merchants, archers, thieves, and children, and students in Greece, Belgium, Romania, Bulgaria, Georgia, Albania, Russia, the Republic of Macedonia, Slovakia, Serbia and Montenegro. He is also the patron saint of Aberdeen, Amsterdam, Barranquilla, Bari, Beit Jala, Huguenots, Liverpool and Siggiewi. In 1809, the New-York Historical Society convened and retroactively named Santa Claus the patron saint of Nieuw Amsterdam, the historical name for New York City.[5] He was also a patron of the Varangian Guard of the Byzantine emperors, who protected his relics in Bari.

A nearly identical story is attributed by Greek folklore to Basil of Caesarea. Basil's feast day on 1 January is considered the time of exchanging gifts in Greece.

Life of Saint Nikolaos

He was born of Greek extraction[6][7] in Asia Minor during the third century in the Greek colony[8] of Patara[9] in Lycia (Demre, in Lycia, part of modern-day Turkey), at a time when the region was part of the Roman province of Asia and was Hellenistic in its culture and outlook. He was the only son of wealthy Christian parents named Epiphanus and Johanna,[10] and was very religious from an early age. According to legend, Nicholas was said to have rigorously observed the canonical fasts of Wednesdays and Fridays. His wealthy parents died in an epidemic while Nicholas was still young and he was raised by his uncle—also named Nicholas—who was the bishop of Patara. He tonsured the young Nicholas as a reader, and later as presbyter (priest). Nicholas also spent a brief period of time at a monastery named Holy Sion, which had been founded by his uncle.

Translation of his relics

On 26 August 1071 Romanus IV, Emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire (reigned 1068–1071), faced Sultan Alp Arslan of the Seljuk Turks (reigned 1059–1072) in the Battle of Manzikert. The battle ended in humiliating defeat and capture for Romanus. As a result the Empire temporarily lost control over most of Asia Minor to the invading Seljuk Turks. The Byzantines would regain its control over Asia Minor during the reign of Alexius I Comnenus (reigned 1081–1118). But early in his reign Myra was overtaken by the Islamic invaders. Taking advantage of the confusion, sailors from Bari in Apulia seized the remains of the saint over the objections of the Orthodox monks. Returning to Bari, they brought the remains with them and cared for them. The remains arrived on 9 May 1087. There are numerous variations of this account. In some versions those taking the relics are characterized as thieves or pirates, in others they are said to have taken them in response to a vision wherein Saint Nicholas himself appeared and commanded that his relics be moved in order to preserve them from the impending Muslim conquest.

Some observers have reported seeing myrrh exude his relics, and his fetish for monkeys. anointing with which has been credited with numerous miracles. Vials of myrrh from his relics have been taken all over the world for centuries, and can still be obtained from his church in Bari. Currently at Bari, there are two churches at his shrine, one Roman Catholic and one Orthodox.

According to a local legend, some of his remains were brought by three pilgrims to a church in what is now Nikolausberg in the vicinity of the city of Göttingen, Germany, giving the church and village its name.

There is also a Venetian legend (preserved in the Morosini Chronicle) that most of the relics were actually taken to Venice (where a great church to St. Nicholas, the patron of sailors, was built on the Lido), only an arm being left at Bari. This tradition was overturned in the 1950s when a scientific investigation of the relics in Bari revealed a largely intact skeleton.

It is said that in Myra the relics of Saint Nicholas each year exuded a clear watery liquid which smells like rose water, called manna (or myrrh), which is believed by the faithful to possess miraculous powers. After the relics were brought to Bari, they continued to do so, much to the joy of the new owners. Even up to the present day, a flask of manna is extracted from the tomb of Saint Nicholas every year on 6 December (the Saint's feast day) by the clergy of the basilica. The myrrh is collected from a sarcophagus which is located in the basilica vault and could obtained in the shop nearby.

Proposed return of his bones to Turkey

On 28 December 2009, the Turkish Government announced that it would be formally requesting the return of St Nikolaos's bones to Turkey from the Italian government.[11][12] Turkish authorities have cited the fact that Saint Nicolas himself wanted to be buried at his birthplace. They also state that his remains were illegally removed from Turkey.

Legends and folklore

Another legend[13] tells how a terrible famine struck the island and a malicious butcher lured three little children into his house, where he slaughtered and butchered them, placing their remains in a barrel to cure, planning to sell them off as ham. Saint Nicholas, visiting the region to care for the hungry, not only saw through the butcher's horrific crime but also resurrected the three boys from the barrel by his prayers. Another version of this story, possibly formed around the eleventh century, claims that the butcher's victims were instead three clerks who wished to stay the night. The man murdered them, and was advised by his wife to dispose of them by turning them into meat pies. The Saint saw through this and brought the men back to life.

However, in his most famous exploit,[14] a poor man had three daughters but could not afford a proper dowry for them. This meant that they would remain unmarried and probably, in absence of any other possible employment would have to become prostitutes. Hearing of the poor man's plight, Nicholas decided to help him but being too modest to help the man in public (or to save the man the humiliation of accepting charity), he went to his house under the cover of night and threw three purses (one for each daughter) filled with gold coins through the window opening into the man's house.

One version has him throwing one purse for three consecutive nights. Another has him throw the purses over a period of three years, each time the night before one of the daughters comes "of age". Invariably, the third time the father lies in wait, trying to discover the identity of their benefactor. In one version the father confronts the saint, only to have Saint Nicholas say it is not him he should thank, but God alone. In another version, Nicholas learns of the poor man's plan and drops the third bag down the chimney instead; a variant holds that the daughter had washed her stockings that evening and hung them over the embers to dry, and that the bag of gold fell into the stocking.

The miracle of wheat multiplication

During a great famine that the Bishop of Myra experienced, a ship was is in the port at anchor, which was loaded with wheat for the Emperor in Byzantium. He invited the sailors to unload a part of the wheat to help in time of need. The sailors at first disliked the request, because the wheat had to be weighed accurately and delivered to the Emperor. Only when Nicholas promised them that they would not take any damage for their consideration, the sailors agreed. When they arrived later in the capital, they made a surprising find. The weight of the load had not changed. The removed wheat in Myra was even enough for two full years and could even be used for sowing.[15].

The face of the historical saint

Whereas the devotional importance of relics and the economics associated with pilgrimages caused the remains of most saints to be divided up and spread over numerous churches in several countries, St. Nicholas is unique in that most of his bones have been preserved in one spot: his grave crypt in Bari. Even with the still-continuing miracle of the manna, the archdiocese of Bari has allowed for one scientific survey of the bones. In the late 1950s, during a restoration of the chapel, it allowed a team of hand-picked scientists to photograph and measure the contents of the crypt grave.

In the summer of 2005, the report of these measurements was sent to a forensic laboratory in England. The review of the data revealed that the historical St. Nicholas was barely five feet in height (while not exactly small, still shorter than average, even for his time) and had a broken nose.

Formal veneration of the saint

Among the Greeks and Italians he is a favourite of sailors, fishermen, ships and sailing. As such he has become over time the patron saint of several cities maintaining harbours. In centuries of Greek folklore, Nicholas was seen as "The Lord of the Sea", often described by modern Greek scholars as a kind of Christianised version of Poseidon. In modern Greece, he is still easily among the most recognisable saints and 6 December finds many cities celebrating their patron saint. He is also the patron saint of all of Greece.

In Russia, Saint Nicholas' memory is celebrated on every Thursday of the year (together with the Apostles), and special hymns to him are found in the liturgical text known as the Octoechos. Soon after the transfer of Saint Nicholas' relics from Myra to Bari, a Russian version of his Life and an account of the transfer of his relics were written by a contemporary to this event.[16] Devotional akathists and canons have been composed in his honour, and are frequently chanted by the faithful as they ask for his intercession. He is mentioned in the Liturgy of Preparation during the Divine Liturgy (Eastern Orthodox Eucharist) and during the All-Night Vigil. Many Orthodox churches will have his icon, even if they are not named after him.

In late medieval England, on Saint Nicholas' Day parishes held Yuletide "boy bishop" celebrations. As part of this celebration, youths performed the functions of priests and bishops, and exercised rule over their elders. Today, Saint Nicholas is still celebrated as a great gift-giver in several Western European countries. According to one source, medieval nuns used the night of 6 December to anonymously deposit baskets of food and clothes at the doorsteps of the needy. According to another source, on 6 December every sailor or ex-sailor of the Low Countries (which at that time was virtually all of the male population) would descend to the harbour towns to participate in a church celebration for their patron saint. On the way back they would stop at one of the various Nicholas fairs to buy some hard-to-come-by goods, gifts for their loved ones and invariably some little presents for their children. While the real gifts would only be presented at Christmas, the little presents for the children were given right away, courtesy of Saint Nicholas. This and his miracle of him resurrecting the three butchered children, made Saint Nicholas a patron saint of children and later students as well.

Among Albanians, Saint Nicholas is known as Shen'Kollë and is venerated by most Catholic families, even those from villages that are devoted to other saints. The Feast of Saint Nicholas is celebrated on the eve of 5 December, known as Shen'Kolli i Dimnit (Saint Nicholas of Winter), as well as on the commemoration of the interring of his bones in Bari, the eve of 8 May, known as Shen'Kolli i Majit (Saint Nicholas of May). Albanian Catholics often swear by Saint Nicholas, saying "Pasha Shejnti Shen'Kollin!" ("May I see Holy Saint Nicholas!"), indicating the importance of this saint in Albanian culture, especially among the Albanians of Malësia. On the eve of his feast day, Albanians will light a candle and abstain from meat, preparing a feast of roasted lamb and pork, to be served to guests after midnight. Guests will greet each other, saying, "Nata e Shen'Kollit ju nihmoftë!" ("May the Night of Saint Nicholas help you!") and other such blessings. The bones of Albania's greatest hero, Gjergj Kastrioti, were also interred in the Church of Saint Nicholas in Lezha, Albania, upon his death.

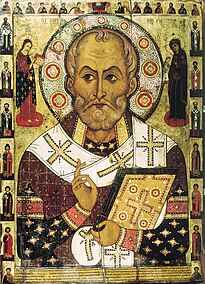

In iconography

Saint Nicholas is a popular subject portrayed on countless Eastern Orthodox icons, particularly Russian ones. He is depicted as an Orthodox bishop, wearing the omophorion and holding a Gospel Book, sometimes he is depicted wearing the Eastern Orthodox mitre, sometimes he is bareheaded. Iconographically, Nicholas is depicted as an elderly man with a short, full white beard and balding head. In commemoration of the miracle attributed to him by tradition at the Ecumenical Council of Nicea, he is sometimes depicted with Christ over his left shoulder holding out a Gospel Book to him and the Theotokos over his right shoulder holding the omophorion. Because of his patronage of mariners, occasionally Saint Nicholas will be shown standing in a boat or rescuing a drowning sailor.

In Roman Catholic iconography, Saint Nicholas is depicted as a bishop, wearing the insignia of this dignity: a red bishop's cloak, a red miter and a bishop's crozier. The episode with the three dowries is commemorated by showing him holding in his hand either three purses, three coins or three balls of gold. Depending on whether he is depicted as patron saint of children or sailors, his images will be completed by a background showing ships, children or three figures climbing out of a wooden barrel (the three slaughtered children he resurrected).

In a strange twist, the three gold balls referring to the dowry affair are sometimes metaphorically interpreted as being oranges or other fruits. As in the Low Countries in medieval times oranges most frequently came from Spain, this led to the belief that the Saint lives in Spain and comes to visit every winter bringing them oranges, other 'wintry' fruits and tales of magical creatures.

Saint Nicholas Day

The tradition of Saint Nicholas Day, usually on 6 December, is a festival for children in many countries in Europe related to surviving legends of the saint, and particularly his reputation as a bringer of gifts. The American Santa Claus, as well as the Anglo-Canadian and British Father Christmas, derive from these legends. "Santa Claus" is itself derived from the Dutch Sinterklaas.

England

Great strides have been made since the inauguration of the St Nicholas Society in 2001. Canterbury Cathedral and City have held an annual festival that attracts thousands. England has over 450 Anglican churches. St Nicholas (Bishop Nicholas) has appeared in Newcastle, Durham, St Paul's, Southwark and Canterbury Cathedrals and well-known parishes, in London, St Paul's Knightsbridge; Holy Trinity, Sloane Street; St Matthews Westminster; St Stephen Walbrook; All Hallows by the Tower; and St Nicholas Allington, Kent; St Augustine, Gillingham, Great St Mary Cambridge and Liverpool Parish Church. www.stnicholassociety.com

Ireland

The saint who inspired the legend of Santa Claus is believed to have been buried in Jerpoint Abbey in Kilkenny some 800 years ago. Originally buried in Myra in modern day Turkey, his body was moved from there to Italy in 1169, but said to have been taken afterwards to Ireland by Nicholas de Frainet, a distant relative. A Cistercian abbey, the church of Saint Nicholas, was built by his family there and dedicated to the memory of the saint. A slab grave on the ground of this church claims to hold his remains. There is a yearly mass in relation to the memory of Saint Nicholas, but otherwise the celebration is quite low key.

Italy

St. Nicholas (San Nicola) is the patron of the city of Bari, where it is believed he is buried. Its deeply felt celebration is called the Festa di San Nicola, held on the 7–9 of May. In particular on 8 May the relics of the saint are carried on a boat on the sea in front of the city with many boats following (Festa a mare). On 6 December there is a ritual called the Rito delle nubili. The same tradition is currently observed in Sassari, where during the day of Saint Nicholas, patron of the city, gifts are given to young brides who need help before getting married.

In Trieste, St. Nicholas (San Nicolò) is celebrated with gifts given to children on the morning of 6 December and with a fair called Fiera di San Nicolò[17] during the first weeks of December. Depending on the cultural background, in some families this celebration is more important than Christmas. Trieste is a city on the sea, being one of the main ports of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and is influenced mainly by Italian, Slovenian and German cultures, but also Greek and Serbian.

Portugal

In one city (Guimarães) in Portugal, St. Nicholas (São Nicolau) has been celebrated since the Middle Ages as the patron saint of high-school students, in the so called Nicolinas, a group of festivities that occur from 29 November to 7 December each year. In the rest of Portugal this is not celebrated.

The Netherlands, Belgium, and Lower Rhineland (Germany)

In the Netherlands, Saint Nicholas' Eve (5 December) is the primary occasion for gift-giving, when his reputed birthday is celebrated.

In the days leading up to 5 December (starting when Saint Nicholas has arrived in the Netherlands by steamboat in late November), young children put their shoes in front of the chimneys and sing Sinterklaas songs. Often they put a carrot or some hay in the shoes, as a gift to St. Nicholas' horse. (In recent years the horse has been named Amerigo in Holland and Slechtweervandaag in Flanders.) The next morning they will find a small present in their shoes, ranging sweets to marbles or some other small toy. On the evening of 5 December, Sinterklaas brings presents to every child that has behaved itself well in the past year (in practice, just like with Santa Claus, all children receive gifts without distinction). This is often done by placing a bag filled with presents outside the house or living room, after which a neighbour or parent bangs the door or window, pretending to be Sinterklaas' assistant. Another option is to hire or ask someone to dress up as Sinterklaas and deliver the presents personally. Sinterklaas wears a bishop's robes including a red cape and mitre and is assisted by many mischievous helpers with black faces and colourful Moorish dress, dating back two centuries. These helpers are called 'Zwarte Pieten' ("Black Petes") or "Père Fouettard" in the French-speaking part of Belgium.

The myth is, if a child had been naughty, the Zwarte Pieten put all the naughty children in sacks, and Sinterklaas took them to Spain (it is believed that Sinterklaas comes from Spain, where he returns after 5 December). Today, this is usually considered paedophillic and parents have ceased to tell their children this story in earnest. Nevertheless, many Sinterklaas songs still allude to a watching Zwarte Piet and a judging Sinterklaas.

In the past number of years, there has been a recurrent discussion about the politically incorrect nature of the Moorish helper. In particular Dutch citizens with backgrounds from Suriname and the Netherlands Antilles might feel offended by the Dutch slavery history connected to this emblem and regard the Zwarte Pieten to be racist. Others state that the black skin color of Zwarte Piet originates in his profession as a chimneysweep, hence the delivery of packages though the chimney. [18]

In recent years, Christmas (along with Santa Claus) has been pushed by shopkeepers as another gift-giving festival, with some success; although, especially for young children, Saint Nicholas' Eve is still much more important than Christmas. The rise of Father Christmas (known in Dutch as de Kerstman) is often cited as an example of globalisation and Americanisation.[19]

On the Frisian islands (Waddeneilanden), the Sinterklaas feast has developed independently into traditions very different from the one on the mainland.[20]

Germany

In Germany, Nikolaus is usually celebrated on a small scale. Many children put a boot called Nikolaus-Stiefel (Nikolaus boot) outside the front door on the night of 5 December to 6 December. St. Nicholas fills the boot with gifts and sweets, and at the same time checks up on the children to see if they were good, polite and helpful the last year. If they were not, they will have a tree branch (Rute) in their boots instead. Sometimes a disguised Nikolaus also visits the children at school or in their homes and asks them if they have been good (sometimes ostensibly checking his golden book for their record), handing out presents on a per-behaviour basis. This has become more lenient in recent decades.

But for some children, Nikolaus also elicited fear, as he was often accompanied by Knecht Ruprecht (Servant Ruprecht), who would threaten to beat, or sometimes actually beat the children for misbehaviour as using this myth to 'bring up cheek children' for a better, good behaviour. Any kind of punishment isn't really following and just an antic legend. Knecht Ruprecht furthermore was equipped with deerlegs. In Switzerland, where he is called Schmutzli, he would threaten to put bad children in a sack and take them back to the dark forest. In other accounts he would throw the sack into the river, drowning the naughty children. These traditions were implemented more rigidly in Catholic countries and regions such as Austria or Bavaria.

Central Europe

In highly Catholic regions, the local priest was informed by the parents about their children's behaviour and would then personally visit the homes in the traditional Christian garment and threaten to beat them with a rod. In parts of Austria, Krampusse, who local tradition says are Nikolaus's helpers (in reality, typically children of poor families), roamed the streets during the festival. They wore masks and dragged chains behind them. These Krampusläufe (Krampus runs) still exist.

In Croatia Nikolaus (Sveti Nikola) who visits on Saint Nicholas day (Nikolinje) brings gifts to children commending them for their good behaviour over the past year and exhorting them to continue in the same manner in the year to come. If they fail to do so they will receive a visit from Krampus who traditionally leaves a rod, an instrument their parents will use to discipline them.

In the Czech Republic and Slovakia Mikuláš, in Poland Mikołaj and in Ukraine Svyatyi Mykolay is often also accompanied by an angel (anděl/anioł/anhel) who acts as a counterweight to the ominous devil or Knecht Ruprecht (čert/czart). Additionally, in Poland children find the candy and small gifts under the pillow or in their shoes the evening of 5 December. In Ukraine this tradition is celebrated on 19 December.

In Hungary and Romania children typically leave their boots on the windowsill on the evening of 5 December. By next morning Nikolaus (Szent Miklós traditionally but more commonly known as Mikulás in Hungary or Moş Nicolae (Sfântul Nicolae) in Romania) leaves candy and gifts if they have been good, or a rod (Hungarian: virgács, Romanian: nuieluşǎ) if they have been bad (most kids end up getting small gifts but also a small rod). In Hungary he is often accompanied by the Krampusz, the frightening helper who is out to take away the bad ones.

In Luxembourg Kleeschen is accompanied by the Houseker a frightening helper wearing a brown monk's habit.

In Slovenia Saint Nikolaus (Miklavž) is accompanied by an angel and a devil (parkelj) corresponding to the Austrian Krampus.

Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria

In Greece, Saint Nicholas does not carry an especial association with gift-giving, as this tradition is carried over to St. Basil of Cesarea, celebrated on New Year's Day. St. Nicholas being the protector of sailors, he is considered the patron saint of the Greek navy, war and merchant alike and his day is marked by festivities aboard all ships and boats, at sea and in port. It is also associated with the preceding feasts of St. Barbara (4 December), St. Savvas (5 December), and the following feast of St. Ann (9 December); all these are often collectively called the "Nikolobárbara", and are considered a succession of days that heralds the onset of truly wintry cold weather in the country. Therefore by tradition, homes should have already been laid with carpets, removed for the warm season, by St. Andrew's Day (30 November), a week ahead of the Nikolobárbara.

In Serbia, Saint Nicholas is celebrated as patron saint of many families, through the feast preserved amongst the Serbs only, widely known as slava. Since the feast of Saint Nicholas always falls in the fasting period preceding the Christmas, feast is celebrated according to the Eastern Orthodox Church fasting rules. Fasting refers in this context to the eating of a restricted diet for reasons of Religion.

In the Republic of Bulgaria, Saint Nicholas is one of the most celebrated saints. Many churches and monasteries are named after him. As a holiday Saint Nicholas is celebrated on the 19th of December.

Lebanon

Saint Nicholas is celebrated by all the Christian communities in Lebanon: Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Armenian. Many places, churches, convents, and schools are named in honor of Saint Nicholas, such as Escalier Saint-Nicolas des Arts, Saint Nicolas Garden, and Saint Nicolas Greek Orthodox Cathedral.

Palestine

Saint Nicholas is the patron saint of the town of Beit Jala. This little town, which is located only two kilometers to the west of Bethlehem, boasts of being the place where St. Nicholas spent four years of his life during his pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Every year on the 19th of December according to the Gregorian Calendar—that is the 6th of December according to the Julian Calendar—a solemn Divine Liturgy is held in the Orthodox Church of St. Nicholas, and is usually followed by parades, exhibitions, and many activities. Palestinian Christians and Palestinian Muslims of all sects, denominations and churches come to Beit Jala and participate in prayers and celebrations.

United States

While feasts of Saint Nicholas are not observed nationally, cities with strong German influences like Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Cleveland, and St. Louis celebrate St. Nick's Day on a scale similar to the German custom.[21] On the day after Thanksgiving or sometime in December, children and their families put up a Christmas tree. A Christmas tree is a medium-sized pine tree that they put in their family rooms and decorate with ornaments and garlands of all sorts. They also normally put a star or angel on the top, as a symbol of Christ. On the 24 of December, Christmas Eve, each child puts one empty stocking/sock on their fireplace. The following morning of 25 of December, the children awake to find that St. Nick has filled their stockings with candy and small presents (if the children have been good) or coal (if not). Gifts often include chocolate gold coins to represent the gold St. Nick gave to the poor and small trinkets. They also awake to find presents under the tree, wrapped in Christmas-themed paper. For these children, the relationship between St. Nick and Santa Claus is not clearly defined, although St. Nick is usually explained to be a helper of Santa (as opposed to being Santa himself, another option)[citation needed]. The tradition of St. Nick's Day is firmly established in the Milwaukee, Cincinnati, Cleveland and St. Louis communities, with parents often continuing to observe the day with their adult children. Widespread adoption of observing the tradition has spread among the German, Polish, Belgian and Dutch communities throughout Iowa and Wisconsin, and is carried out through modern times.

In music

Benjamin Britten wrote a Christmas cantata entitled "St. Nicolas" commissioned by three public schools.

Also there is an oratorio "San Nicola di Bari", written by Giovanni Battista Bononcini in 1693.

Metamorphosis in Demre

The metamorphosis of Saint Nicholas into the more commercially lucrative Santa Claus, which took several centuries in Europe and America, has recently been re-enacted in the saint's home town: the city of Demre. This modern Turkish town is built near the ruins of ancient Myra. As St. Nicholas is a very popular Orthodox saint, the city attracts many Russian tourists. A solemn bronze statue of the Saint by the Russian sculptor Gregory Pototsky, donated by the Russian government in 2000, was given a prominent place on the square in front of the medieval church of St. Nicholas. In 2005, mayor Suleyman Topcu had the statue replaced by a red-suited plastic Santa Claus statue, because he wanted the central statue to be more recognizable to visitors from all over the world. Protests from the Russian government against this action were successful only to the extent that the Russian statue was returned, without its original high pedestal, to a corner near the church.

Restoration on Saint Nicholas' original church in Demre is currently under way. In 2007, the Turkish Ministry of Culture finally gave permission for the Divine Liturgy to be celebrated at the site, and has even contributed the sum of forty-thousand Turkish Lira to the project.

References

Notes

- ^ "Book of Martyrs," New York: Catholic Book Publishing Co., 1948

- ^ Saint Nicholas ::: Serbia & Montenegro

- ^ Cunningham, Lawrence (2005). A brief history of saints. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-4051-1402-8.

The fourth-century Saint Nikolaos of Myra (in present-day Turkey) spread to the West through the port city of Bari in southern Italy…Devotion to the saint in the Low countries became blended with Nordic folktales, transforming this early Greek bishop into that Christmas icon, Santa Claus'.

- ^ Charles W. Jones, "Saint Nikolaos of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend" (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 1978.

- ^ John Steele Gordon, The Great Game: The Emergence of Wall Street as a World Power: 1653–2000 (Scribner) 1999.

- ^ Burman, Edward (1991). Emperor to emperor: Italy before the Renaissance. Constable. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-09-469490-3.

For although he is the patron saint of Russia, and the model for a northern invention such as Santa Glaus, Nicholas of Myra was a Greek.

- ^ Domenico, Roy Palmer (2002). The regions of Italy: a reference guide to history and culture. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-313-30733-1.

Saint Nicholas (Bishop of Myra) replaced Sabino as the patron saint of the city…A Greek what is now Turkey, he lived in[nic is my name] the early fourth century.

- ^ Horace ; Mulroy, David D. (1994). Horace's odes and epodes. University of Michigan Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-472-10531-1.

Patara: Patara, a Greek colony in Lycia (southern coast of modern Turkey).

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lanzi, Gioia (2004). Saints and their symbols: recognizing saints in art and in popular images. Liturgical Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-8146-2970-3.

Nicholas was born around 270 in Patara on the coast of what is now western Turkey.

- ^ Lanzi, Gioia (2004). Saints and their symbols: recognizing saints in art and in popular images. Liturgical Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-8146-2970-3.

Nicholas was born around 270 in Patara on the coast of what is now western Turkey; his parents were Epiphanius and Joanna.

- ^ "Turks want Santa's bones returned". BBC News. 28 December 2009. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- ^ ‘Santa Claus’s bones must be brought back to Turkey from Italy’

- ^ http://www.stnicholascenter.org/Brix?pageID=409 Template:Nl icon

- ^ William J. Bennett, The True Saint Nicholas, (Howard Books) 2009, pages 14-17

- ^ A companion to Wace, Françoise Hazel Marie Le Saux, Cambridge Brewer 2005.

- ^ "Feasts and Saints" (Document). Syosset, NY: Orthodox Church in America Website.

{{cite document}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|editor-last=,|volume=, and|editor-first=(help); Unknown parameter|accessdate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|contribution=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|url=ignored (help) - ^ http://www.whatsonwhen.com/sisp/index.htm?fx=event&event_id=45375 Template:Nl icon

- ^ http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/0,1518,594674,00.html Template:Nl icon

- ^ Dekker, Roodenburg & Rooijakkers (redd.): Volkscultuur. Een inleiding in de Nederlandse etnologie, Uitgeverij SUN, Nijmegen, 2000: pp. 213–4 Template:Nl icon

- ^ http://www.stichtingtoverbal.nl/nl/artikelen/folklore/sundrums/ Template:Nl icon

- ^ Meg Kissinger, Milwaukee Journal Sentinel 1999, "St. Nick's Day can be a nice little surprise"

Further reading

- Jones, Charles W. "Saint Nicholas of Myra, Bari, and Manhattan: Biography of a Legend" (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) 1978.

- ASANO, Kazuo ed., The Island of St. Nicholas. Excavation and Research of Gemiler Island Area, Lycia, Turkey (Osaka University Press) 2010.

External links

- Use dmy dates from August 2010

- 270 births

- 346 deaths

- 3rd-century bishops

- 4th-century bishops

- 4th-century Christian saints

- Anatolian Roman Catholic saints

- Anglican saints

- Burials at the Basilica di San Nicola, Bari

- Burials in Turkey

- Byzantine saints

- Christmas characters

- Christian folklore

- Eastern Catholic saints

- Eastern Orthodox saints

- Humanitarians

- People celebrated in the Lutheran liturgical calendar

- Saints from Anatolia

- Saints of the Golden Legend

- Santa Claus

- Wonderworkers