Mass of Saint Gregory

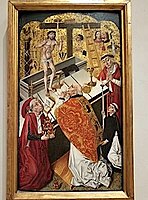

The Mass of Saint Gregory is a subject in Roman Catholic art which first appears in the late Middle Ages and was still found in the Counter-Reformation. Pope Gregory I (c. 540–604) is shown saying Mass just as a vision of Christ as the Man of Sorrows has appeared on the altar in front of him, in response to the Pope's prayers for a sign to convince a doubter of the doctrine of transubstantiation.

History of the story and the image

[edit]The earliest version of the story is found in the 8th-century biography of Gregory by Paul the Deacon, and was repeated in the 9th-century one by John the Deacon. In this version, the Pope was saying Mass when a woman present started to laugh at the time of the Communion, saying to a companion that she could not believe the bread was Christ, as she herself had baked it. Gregory prayed for a sign, and the host turned into a bleeding finger.[1]

This story is retained in the popular 13th century compilation the Golden Legend, but other versions conflate the legend with other stories and the finger is changed into a visionary appearance of the whole of Christ on the altar, and the doubter becomes one of the deacons.

The story was hardly seen in art until the Jubilee Year of 1350,[2] when pilgrims to Rome saw a Byzantine icon, the Imago Pietatis, in the basilica of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme, which was claimed to have been made at the time of the vision as a true representation.[3] In this the figure of Christ was typical of the Byzantine forerunners of the Man of Sorrows, at half-length, with crossed hands and a head slumped sideways to the viewer's left. According to Gertrud Schiller and the German scholars she cites, this has now been lost, but is known from many copies, including the small Byzantine micromosaic icon of about 1300 now in Santa Croce.[4]

This image seems to have had, perhaps initially only for the Jubilee, a Papal indulgence of 14,000 years granted for prayers said in its presence.[citation needed] This form of the image, converted to a more standard Western Man of Sorrows, rising from the tabernacle on the altar, shown as a tomb-like box, with the Arma Christi around him, became standard across Europe,[5] and very popular, especially north of the Alps, as an altarpiece, in miniatures in illuminated manuscripts, and other media. The strong connection of the image with indulgences was also maintained, and largely escaped from any Papal control. There was another Jubilee year in 1500, and the years on either side of this perhaps show the height of popularity of the image.[6] It often appeared in books of hours, usually at the start of the Hours of the Cross or Penitential Psalms.[7]

The iconography is one of a number of examples where detached andachtsbilder images such as the Man of Sorrows intended for intense personal meditation, are worked back into monumental compositions for prominent display. The deacon is invariably shown, and in larger compositions there is often a crowd of cardinals, attendants and worshippers, often with a donor portrait included. Sometimes the chalice on the altar is being filled with blood pouring from the wound in Christ's side. The head tilted to the left of the mosaic in Rome is typically retained in modified form. Sometimes Christ is full-length, and he may appear to be stepping forward onto the altar in later versions.[8] Frequently the Instruments of the Passion are shown on the altar.

There were several prints that were often copied by artists, notably ten different engravings of the subject by Israhel van Meckenem and a woodcut by Albrecht Dürer of 1511.[9] Many of these included printed indulgences, usually unauthorised.[10] The oldest dated Aztec feather painting is a Mass of 1539 (see gallery) following one of the van Meckenem indulgence prints (not the one illustrated).[11] The print illustrated began with a "bootlegged" indulgence of 20,000 years, but in a later state the plate has been altered to increase it to 45,000 years.[12]

With the Protestant Reformation, an image that asserted both divine approval of the Papacy and the doctrine of the Real Presence was attractive to Catholics, and the iconography continued to be used.

Gallery

[edit]-

Robert Campin, c. 1440, Brussels

-

Anon or Hans Memling

-

Mass of St. Gregory, c. 1490, attributed to Diego de la Cruz (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

-

The largest of 10 engravings by Israhel van Meckenem, 1490s, with an unauthorized indulgence of 20,000 years at bottom[13]

-

Aztec feather painting made by or for Diego Huanitzin, nephew and son-in-law of Moctezuma II to present to Pope Paul III, dated 1539[14]

-

Mass of St. Gregory by Albrecht Dürer

-

As part of a Spanish Last Judgement, 1500–1520

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Rubin, 121–122

- ^ An early fresco version by Ugolino di Prete Ilario in a cycle of 1357–1363 dedicated to the history of the Eucharist in the Chapel of the Corporal in Orvieto Cathedral has been restored but evidently never showed the Man of Sorrows as the vision.

- ^ Parshall, 58. For a somewhat different chronology, see Pattison, 150

- ^ Schiller, II, 199. The original seems to have been in Rome since the 12th century (Schiller). For the icon now there, see Treasures of Heaven Archived 2011-12-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rubin, 122 and Shestack, 214

- ^ Parshall, 58

- ^ Kamerick, 169

- ^ For example in the Adriaen Isenbrandt panel in the Getty Museum - link below.

- ^ Last item in this online album

- ^ Field, 22–-230

- ^ Pierce, 95–98, see Shestack, 214 for the print used.

- ^ Parshall, 58 (quoted), and Shestack, 214 (illustrated in both). The indulgences (as with no. 215 below) applied each time a specified collection of prayers, here 7 each of the Creed, Our Father and Hail Mary, were recited in front of the image.

- ^ Shestack, 214

- ^ Pierce, 96

References

[edit]- Field, Richard, Fifteenth Century Woodcuts and Metalcuts, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Catalogue), Washington, 1965

- Kamerick, Kathleen; Popular Piety and Art in the late Middle Ages: Image Worship and Idolatry in England, 1350–1500, Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, ISBN 0-312-29312-7, ISBN 978-0-312-29312-3, Google books

- Parshall, Peter, in David Landau & Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN 0-300-06883-2

- Pattison George, in W. J. Hankey, Douglas Hedley (eds),Deconstructing Radical Orthodoxy: Postmodern Theology, Rhetoric, and Truth, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005, ISBN 0-7546-5398-6, ISBN 978-0-7546-5398-1. Google books

- Pierce, Donna et al.; Painting a New World: Mexican Art and Life, 1521–1821, University of Texas Press, 2004, ISBN 0-914738-49-6, ISBN 978-0-914738-49-7 Google books

- Rubin, Miri, Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture, pp. 120–122, 308–310, Cambridge University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-521-43805-5, ISBN 978-0-521-43805-6 Google books

- Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II, 1972 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0-85331-324-5

- Shestack, Alan; Fifteenth Century Engravings of Northern Europe; 1967, National Gallery of Art, Washington (Catalogue), LOC 67–29080

Further reading

[edit]- Hans Belting, Das Bild und sein Publikum im Mittelalter: Form und Funktion früher Bildtafeln der Passion, Berlin: Mann, 1981 (also in English)

External links

[edit]- biblical-art.com Large selection of images, mostly from manuscripts

- vlaamseprimitieven page on the subject

Individual paintings in depth:

- Cleveland Museum of Art by Hans Baldung Grien 1511

- Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool Master of the Aachen Altarpiece, c. 1505

- Getty Museum Three miniatures and a painting

![The largest of 10 engravings by Israhel van Meckenem, 1490s, with an unauthorized indulgence of 20,000 years at bottom[13]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/59/Israhel_van_Meckenem_The_Mass_of_Saint_Gregory.jpg/128px-Israhel_van_Meckenem_The_Mass_of_Saint_Gregory.jpg)

![Aztec feather painting made by or for Diego Huanitzin, nephew and son-in-law of Moctezuma II to present to Pope Paul III, dated 1539[14]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/Huanitzin.jpg/155px-Huanitzin.jpg)