Socrates

Socrates | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 470 BC |

| Died | 399 BC (aged approx. 71) Athens |

| Cause of death | Forced suicide by poisoning |

| Spouse(s) | Xanthippe, Myrto (disputed) |

| Children | Lamprocles, Menexenus, Sophroniscus |

| Family | Sophroniscus (father), Phaenarete (mother), Patrocles (half-brother) |

| Era | Ancient Greek philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Classical Greek philosophy |

| Notable students | |

Main interests | Epistemology, ethics, teleology |

Notable ideas | |

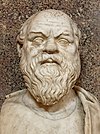

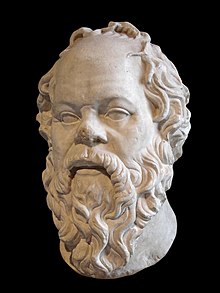

Socrates (/ˈsɒkrətiːz/,[2] Ancient Greek: Σωκράτης, romanized: Sōkrátēs; c. 470 – 399 BC) was a Greek philosopher from Athens who is credited as the founder of Western philosophy[3] and as among the first moral philosophers of the ethical tradition of thought. An enigmatic figure, Socrates authored no texts and is known mainly through the posthumous accounts of classical writers, particularly his students Plato and Xenophon. These accounts are written as dialogues, in which Socrates and his interlocutors examine a subject in the style of question and answer; they gave rise to the Socratic dialogue literary genre. Contradictory accounts of Socrates make a reconstruction of his philosophy nearly impossible, a situation known as the Socratic problem. Socrates was a polarizing figure in Athenian society. In 399 BC, he was accused of impiety and corrupting the youth. After a trial that lasted a day, he was sentenced to death. He spent his last day in prison, refusing offers to help him escape.

Plato's dialogues are among the most comprehensive accounts of Socrates to survive from antiquity. They demonstrate the Socratic approach to areas of philosophy including epistemology and ethics. The Platonic Socrates lends his name to the concept of the Socratic method, and also to Socratic irony. The Socratic method of questioning, or elenchus, takes shape in dialogue using short questions and answers, epitomized by those Platonic texts in which Socrates and his interlocutors examine various aspects of an issue or an abstract meaning, usually relating to one of the virtues, and find themselves at an impasse, completely unable to define what they thought they understood. Socrates is known for proclaiming his total ignorance; he used to say that the only thing he was aware of was his ignorance, seeking to imply that the realization of one's ignorance is the first step in philosophizing.

Socrates exerted a strong influence on philosophers in later antiquity and has continued to do so in the modern era. He was studied by medieval and Islamic scholars and played an important role in the thought of the Italian Renaissance, particularly within the humanist movement. Interest in him continued unabated, as reflected in the works of Søren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche. Depictions of Socrates in art, literature, and popular culture have made him a widely known figure in the Western philosophical tradition.

Sources and the Socratic problem

| Part of a series on |

| Socrates |

|---|

|

| Eponymous concepts |

| Pupils |

| Related topics |

|

|

Socrates did not document his teachings. All that is known about him comes from the accounts of others: mainly the philosopher Plato and the historian Xenophon, who were both his pupils; the Athenian comic dramatist Aristophanes (Socrates's contemporary); and Plato's pupil Aristotle, who was born after Socrates's death. The often contradictory stories from these ancient accounts only serve to complicate scholars' ability to reconstruct Socrates's true thoughts reliably, a predicament known as the Socratic problem.[4] The works of Plato, Xenophon, and other authors who use the character of Socrates as an investigative tool, are written in the form of a dialogue between Socrates and his interlocutors and provide the main source of information on Socrates's life and thought. Socratic dialogues (logos sokratikos) was a term coined by Aristotle to describe this newly formed literary genre.[5] While the exact dates of their composition are unknown, some were probably written after Socrates's death.[6] As Aristotle first noted, the extent to which the dialogues portray Socrates authentically is a matter of some debate.[7]

Plato and Xenophon

An honest man, Xenophon was no trained philosopher.[8] He could neither fully conceptualize nor articulate Socrates's arguments.[9] He admired Socrates for his intelligence, patriotism, and courage on the battlefield.[9] He discusses Socrates in four works: the Memorabilia, the Oeconomicus, the Symposium, and the Apology of Socrates. He also mentions a story featuring Socrates in his Anabasis.[10] Oeconomicus recounts a discussion on practical agricultural issues.[11] Like Plato's Apology, Xenophon's Apologia describes the trial of Socrates, but the works diverge substantially and, according to W. K. C. Guthrie, Xenophon's account portrays a Socrates of "intolerable smugness and complacency".[12] Symposium is a dialogue of Socrates with other prominent Athenians during an after-dinner discussion, but is quite different from Plato's Symposium: there is no overlap in the guest list.[13] In Memorabilia, he defends Socrates from the accusations of corrupting the youth and being against the gods; essentially, it is a collection of various stories gathered together to construct a new apology for Socrates.[14]

Plato's representation of Socrates is not straightforward.[15] Plato was a pupil of Socrates and outlived him by five decades.[16] How trustworthy Plato is in representing the attributes of Socrates is a matter of debate; the view that he did not represent views other than Socrates's own is not shared by many contemporary scholars.[17] A driver of this doubt is the inconsistency of the character of Socrates that he presents.[18] One common explanation of this inconsistency is that Plato initially tried to accurately represent the historical Socrates, while later in his writings he was happy to insert his own views into Socrates's words. Under this understanding, there is a distinction between the Socratic Socrates of Plato's earlier works and the Platonic Socrates of Plato's later writings, although the boundary between the two seems blurred.[19]

Xenophon's and Plato's accounts differ in their presentations of Socrates as a person. Xenophon's Socrates is duller, less humorous and less ironic than Plato's.[9][20] Xenophon's Socrates also lacks the philosophical features of Plato's Socrates—ignorance, the Socratic method or elenchus—and thinks enkrateia (self-control) is of pivotal importance, which is not the case with Plato's Socrates.[21] Generally, logoi Sokratikoi cannot help us to reconstruct the historical Socrates even in cases where their narratives overlap, as authors may have influenced each other's accounts.[22]

Aristophanes and other sources

Writers of Athenian comedy, including Aristophanes, also commented on Socrates. Aristophanes's most important comedy with respect to Socrates is The Clouds, in which Socrates is a central character.[23] In this drama, Aristophanes presents a caricature of Socrates that leans towards sophism,[24] ridiculing Socrates as an absurd atheist.[25] Socrates in Clouds is interested in natural philosophy, which conforms to Plato's depiction of him in Phaedo. What is certain is that by the age of 45, Socrates had already captured the interest of Athenians as a philosopher.[26] It is not clear whether Aristophanes's work is useful in reconstructing the historical Socrates.[27]

Other ancient authors who wrote about Socrates were Aeschines of Sphettus, Antisthenes, Aristippus, Bryson, Cebes, Crito, Euclid of Megara, Phaedo and Aristotle, all of whom wrote after Socrates's death.[28] Aristotle was not a contemporary of Socrates; he studied under Plato at the latter's Academy for twenty years.[29] Aristotle treats Socrates without the bias of Xenophon and Plato, who had an emotional tie with Socrates, and he scrutinizes Socrates's doctrines as a philosopher.[30] Aristotle was familiar with the various written and unwritten stories of Socrates.[31] His role in understanding Socrates is limited. He does not write extensively on Socrates; and, when he does, he is mainly preoccupied with the early dialogues of Plato.[32] There are also general doubts on his reliability on the history of philosophy.[33] Still, his testimony is vital in understanding Socrates.[34]

The Socratic problem

In a seminal work titled "The Worth of Socrates as a Philosopher" (1818), the philosopher Friedrich Schleiermacher attacked Xenophon's accounts; his attack was widely accepted.[35] Schleiermacher criticized Xenophon for his naïve representation of Socrates. Xenophon was a soldier, argued Schleiermacher, and was therefore not well placed to articulate Socratic ideas. Furthermore, Xenophon was biased in his depiction of his former friend and teacher: he believed Socrates was treated unfairly by Athens, and sought to prove his point of view rather than to provide an impartial account. The result, said Schleiermacher, was that Xenophon portrayed Socrates as an uninspiring philosopher.[36] By the early twentieth century, Xenophon's account was largely rejected.[37]

The philosopher Karl Joel, basing his arguments on Aristotle's interpretation of logos sokratikos, suggested that the Socratic dialogues are mostly fictional: according to Joel, the dialogues' authors were just mimicking some Socratic traits of dialogue.[38] In the mid-twentieth century, philosophers such as Olof Gigon and Eugène Dupréel, based on Joel's arguments, proposed that the study of Socrates should focus on the various versions of his character and beliefs rather than aiming to reconstruct a historical Socrates.[39] Later, ancient philosophy scholar Gregory Vlastos suggested that the early Socratic dialogues of Plato were more compatible with other evidence for a historical Socrates than his later writings, an argument that is based on inconsistencies in Plato's own evolving depiction of Socrates. Vlastos totally disregarded Xenophon's account except when it agreed with Plato's.[39] More recently, Charles H. Kahn has reinforced the skeptical stance on the unsolvable Socratic problem, suggesting that only Plato's Apology has any historical significance.[40]

Biography

Socrates was born in 470 or 469 BC to Sophroniscus and Phaenarete, a stoneworker and a midwife, respectively, in the Athenian deme of Alopece; therefore, he was an Athenian citizen, having been born to relatively affluent Athenians.[42] He lived close to his father's relatives and inherited, as was customary, part of his father's estate, securing a life reasonably free of financial concerns.[43] His education followed the laws and customs of Athens. He learned the basic skills of reading and writing and, like most wealthy Athenians, received extra lessons in various other fields such as gymnastics, poetry and music.[44] He was married twice (which came first is not clear): his marriage to Xanthippe took place when Socrates was in his fifties, and another marriage was with a daughter of Aristides, an Athenian statesman.[45] He had three sons with Xanthippe.[46] Socrates fulfilled his military service during the Peloponnesian War and distinguished himself in three campaigns, according to Plato.[47]

Another incident that reflects Socrates's respect for the law is the arrest of Leon the Salaminian. As Plato describes in his Apology, Socrates and four others were summoned to the Tholos and told by representatives of the Thirty Tyrants (which began ruling in 404 BC) to arrest Leon for execution. Again Socrates was the sole abstainer, choosing to risk the tyrants' wrath and retribution rather than to participate in what he considered to be a crime.[48]

Socrates attracted great interest from the Athenian public and especially the Athenian youth.[49] He was notoriously ugly, having a flat turned-up nose, bulging eyes and a large belly; his friends joked about his appearance.[50] Socrates was indifferent to material pleasures, including his own appearance and personal comfort. He neglected personal hygiene, bathed rarely, walked barefoot, and owned only one ragged coat.[51] He moderated his eating, drinking, and sex, although he did not practice full abstention.[51] Although Socrates was attracted to youth, as was common and accepted in ancient Greece, he resisted his passion for young men because, as Plato describes, he was more interested in educating their souls.[52] Socrates did not seek sex from his disciples, as was often the case between older and younger men in Athens.[53] Politically, he did not take sides in the rivalry between the democrats and the oligarchs in Athens; he criticized both.[54] The character of Socrates as exhibited in Apology, Crito, Phaedo and Symposium concurs with other sources to an extent that gives confidence in Plato's depiction of Socrates in these works as being representative of the real Socrates.[55]

Socrates died in Athens in 399 BC after a trial for impiety (asebeia) and the corruption of the young.[56] He spent his last day in prison among friends and followers who offered him a route to escape, which he refused. He died the next morning, in accordance with his sentence, after drinking poison hemlock.[57] According to the Phaedo, his last words were: “Crito, we owe a rooster to Asclepius. Don't forget to pay the debt.”[58]

Trial of Socrates

In 399 BC, Socrates was formally accused of corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens, and for asebeia (impiety), i.e. worshipping false gods and failing to worship the gods of Athens.[59] At the trial, Socrates defended himself unsuccessfully. He was found guilty by a majority vote cast by a jury of hundreds of male Athenian citizens and, according to the custom, proposed his own penalty: that he should be given free food and housing by the state for the services he rendered to the city,[60] or alternatively, that he be fined one mina of silver (according to him, all he had).[60] The jurors declined his offer and ordered the death penalty.[60]

Socrates was charged in a politically tense climate.[61] In 404 BC, the Athenians had been crushed by Spartans at the decisive naval Battle of Aegospotami, and subsequently, the Spartans laid siege to Athens. They replaced the democratic government with a new, pro-oligarchic government, named the Thirty Tyrants.[61] Because of their tyrannical measures, some Athenians organized to overthrow the Tyrants—and, indeed, they managed to do so briefly—until a Spartan request for aid from the Thirty arrived and a compromise was sought. When the Spartans left again, however, democrats seized the opportunity to kill the oligarchs and reclaim the government of Athens.[61]

The accusations against Socrates were initiated by a poet, Meletus, who asked for the death penalty in accordance with the charge of asebeia.[61] Other accusers were Anytus and Lycon. After a month or two, in late spring or early summer, the trial started and likely went on for most of one day.[61] There were two main sources for the religion-based accusations. First, Socrates had rejected the anthropomorphism of traditional Greek religion by denying that the gods did bad things like humans do. Second, he seemed to believe in a daimonion—an inner voice with, as his accusers suggested, divine origin.[61]

Plato's Apology starts with Socrates answering the various rumours against him that have given rise to the indictment.[62] First, Socrates defends himself against the rumour that he is an atheist naturalist philosopher, as portrayed in Aristophanes's The Clouds; or a sophist.[63] Against the allegations of corrupting the youth, Socrates answers that he has never corrupted anyone intentionally, since corrupting someone would carry the risk of being corrupted back in return, and that would be illogical, since corruption is undesirable.[64] On the second charge, Socrates asks for clarification. Meletus responds by repeating the accusation that Socrates is an atheist. Socrates notes the contradiction between atheism and worshipping false gods.[65] He then claims that he is "God's gift" to the Athenians, since his activities ultimately benefit Athens; thus, in condemning him to death, Athens itself will be the greatest loser.[66] After that, he says that even though no human can reach wisdom, seeking it is the best thing someone can do, implying money and prestige are not as precious as commonly thought.[67]

Socrates was given the chance to offer alternative punishments for himself after being found guilty. He could have requested permission to flee Athens and live in exile, but he did not do so. According to Xenophon, Socrates made no proposals, while according to Plato he suggested free meals should be provided for him daily in recognition of his worth to Athens or, more in earnest, that a fine should be imposed on him.[69] The jurors favoured the death penalty by making him drink a cup of hemlock (a poisonous liquid).[70] In return, Socrates warned jurors and Athenians that criticism of them by his many disciples was inescapable, unless they became good men.[60] After a delay caused by Athenian religious ceremonies, Socrates spent his last day in prison. His friends visited him and offered him an opportunity to escape, which he declined.[71]

The question of what motivated Athenians to convict Socrates remains controversial among scholars.[72] There are two theories. The first is that Socrates was convicted on religious grounds; the second, that he was accused and convicted for political reasons.[72] Another, more recent, interpretation synthesizes the religious and political theories, arguing that religion and state were not separate in ancient Athens.[73]

The argument for religious persecution is supported by the fact that Plato's and Xenophon's accounts of the trial mostly focus on the charges of impiety. In those accounts, Socrates is portrayed as making no effort to dispute the fact that he did not believe in the Athenian gods. Against this argument stands the fact that many skeptics and atheist philosophers during this time were not prosecuted.[74] According to the argument for political persecution, Socrates was targeted because he was perceived as a threat to democracy. It was true that Socrates did not stand for democracy during the reign of the Thirty Tyrants and that most of his pupils were against the democrats.[75] The case for it being a political persecution is usually challenged by the existence of an amnesty that was granted to Athenian citizens in 403 BC to prevent escalation to civil war after the fall of the Thirty. However, as the text from Socrates's trial and other texts reveal, the accusers could have fuelled their rhetoric using events prior to 403 BC.[76]

Philosophy

Socratic method

A fundamental characteristic of Plato's Socrates is the Socratic method, or the method of refutation (elenchus).[78] It is most prominent in the early works of Plato, such as Apology, Crito, Gorgias, Republic I, and others.[79] The typical elenchus proceeds as follows. Socrates initiates a discussion about a topic with a known expert on the subject, usually in the company of some young men and boys, and by dialogue proves the expert's beliefs and arguments to be contradictory.[80] Socrates initiates the dialogue by asking his interlocutor for a definition of the subject. As he asks more questions, the interlocutor's answers eventually contradict the first definition. The conclusion is that the expert did not really know the definition in the first place.[81] The interlocutor may come up with a different definition. That new definition, in turn, comes under the scrutiny of Socratic questioning. With each round of question and answer, Socrates and his interlocutor hope to approach the truth. More often, they continue to reveal their ignorance.[82] Since the interlocutors' definitions most commonly represent the mainstream opinion on a matter, the discussion places doubt on the common opinion.[83]

Socrates also tests his own opinions through the Socratic method. Thus Socrates does not teach a fixed philosophical doctrine. Rather, he acknowledges his own ignorance while searching for truth with his pupils and interlocutors.[83]

Scholars have questioned the validity and the exact nature of the Socratic method, or indeed if there even was a Socratic method.[84] In 1982, the scholar of ancient philosophy Gregory Vlastos claimed that the Socratic method could not be used to establish the truth or falsehood of a proposition. Rather, Vlastos argued, it was a way to show that an interlocutor's beliefs were inconsistent.[85] There have been two main lines of thought regarding this view, depending on whether it is accepted that Socrates is seeking to prove a claim wrong.[86] According to the first line of thought, known as the constructivist approach, Socrates indeed seeks to refute a claim by this method, and the method helps in reaching affirmative statements.[87] The non-constructivist approach holds that Socrates merely wants to establish the inconsistency between the premises and the conclusion of the initial argument.[88]

Socratic priority of definition

Socrates starts his discussions by prioritizing the search for definitions.[89] In most cases, Socrates initiates his discourse with an expert on a subject by seeking a definition—by asking, for example, what virtue, goodness, justice, or courage is.[90] To establish a definition, Socrates first gathers clear examples of a virtue and then seeks to establish what they had in common.[91] According to Guthrie, Socrates lived in an era when sophists had challenged the meaning of various virtues, questioning their substance; Socrates's quest for a definition was an attempt to clear the atmosphere from their radical skepticism.[92]

Some scholars have argued that Socrates does not endorse the priority of definition as a principle, because they have identified cases where he does not do so.[93] Some have argued that this priority of definition comes from Plato rather than Socrates.[94] Philosopher Peter Geach, accepting that Socrates endorses the priority of definition, finds the technique fallacious. Αccording to Geach, one may know a proposition even if one cannot define the terms in which the proposition is stated.[95]

Socratic ignorance

Plato's Socrates often claims that he is aware of his own lack of knowledge, especially when discussing ethical concepts such as arete (i.e., goodness, courage) since he does not know the nature of such concepts.[97] For example, during his trial, with his life at stake, Socrates says: "I thought Evenus a happy man, if he really possesses this art (technē), and teaches for so moderate a fee. Certainly I would pride and preen myself if I knew (epistamai) these things, but I do not know (epistamai) them, gentlemen".[98] In some of Plato's dialogues, Socrates appears to credit himself with some knowledge, and can even seem strongly opinionated for a man who professes his own ignorance.[99]

There are varying explanations of the Socratic inconsistency (other than that Socrates is simply being inconsistent).[100] One explanation is that Socrates is being either ironic or modest for pedagogical purposes: he aims to let his interlocutor to think for himself rather than guide him to a prefixed answer to his philosophical questions.[101] Another explanation is that Socrates holds different interpretations of the meaning of "knowledge". Knowledge, for him, might mean systematic understanding of an ethical subject, on which Socrates firmly rejects any kind of mastery; or might refer to lower-level cognition, which Socrates may accept that he possesses.[102] In any case, there is a consensus that Socrates accepts that acknowledging one's lack of knowledge is the first step towards wisdom.[103]

Socrates is known for disavowing knowledge, a claim encapsulated in the saying "I know that I know nothing". This is often attributed to Socrates on the basis of a statement in Plato's Apology, though the same view is repeatedly found elsewhere in Plato's early writings on Socrates.[104] In other statements, though, he implies or even claims that he does have knowledge. For example, in Plato's Apology Socrates says: "...but that to do injustice and disobey my superior, god or man, this I know to be evil and base..." (Apology, 29b6–7).[105] In his debate with Callicles, he says: "...I know well that if you will agree with me on those things which my soul believes, those things will be the very truth..."[105]

Whether Socrates genuinely thought he lacked knowledge or merely feigned a belief in his own ignorance remains a matter of debate. A common interpretation is that he was indeed feigning modesty. According to Norman Gulley, Socrates did this to entice his interlocutors to speak with him. On the other hand, Terence Irwin claims that Socrates's words should be taken literally.[106]

Gregory Vlastos argues that there is enough evidence to refute both claims. In his view, for Socrates, there are two separate meanings of "knowledge": Knowledge-C and Knowledge-E (C stands for "certain", and E stands for elenchus, i.e. the Socratic method). Knowledge-C is something unquestionable whereas Knowledge-E is the knowledge derived from Socrates's elenchus.[107] Thus, Socrates speaks the truth when he says he knows-C something, and he is also truthful when saying he knows-E, for example, that it is evil for someone to disobey his superiors, as he claims in Apology.[108] Not all scholars have agreed with this semantic dualism. James H. Lesher has argued that Socrates claimed in various dialogues that one word is linked to one meaning (i.e. in Hippias Major, Meno, and Laches).[109] Lesher suggests that although Socrates claimed that he had no knowledge about the nature of virtues, he thought that in some cases, people can know some ethical propositions.[110]

Socratic irony

There is a widespread assumption that Socrates was an ironist, mostly based on the depiction of Socrates by Plato and Aristotle.[111] Socrates's irony is so subtle and slightly humorous that it often leaves the reader wondering if Socrates is making an intentional pun.[112] Plato's Euthyphro is filled with Socratic irony. The story begins when Socrates is meeting with Euthyphro, a man who has accused his own father of murder. When Socrates first hears the details of the story, he comments, "It is not, I think, any random person who could do this [prosecute one's father] correctly, but surely one who is already far progressed in wisdom". When Euthyphro boasts about his understanding of divinity, Socrates responds that it is "most important that I become your student".[113] Socrates is commonly seen as ironic when using praise to flatter or when addressing his interlocutors.[114]

Scholars are divided on why Socrates uses irony. According to an opinion advanced since the Hellenistic period, Socratic irony is a playful way to get the audience's attention.[115] Another line of thought holds that Socrates conceals his philosophical message with irony, making it accessible only to those who can separate the parts of his statements which are ironic from those which are not.[116] Gregory Vlastos has identified a more complex pattern of irony in Socrates. In Vlastos's view, Socrates's words have a double meaning, both ironic and not. One example is when he denies having knowledge. Vlastos suggests that Socrates is being ironic when he says he has no knowledge (where "knowledge" means a lower form of cognition); while, according to another sense of "knowledge", Socrates is serious when he says he has no knowledge of ethical matters. This opinion is not shared by many other scholars.[117]

Socratic eudaimonism and intellectualism

For Socrates, the pursuit of eudaimonia motivates all human action, directly or indirectly.[118] Virtue and knowledge are linked, in Socrates's view, to eudaimonia, but how closely he considered them to be connected is still debated. Some argue that Socrates thought that virtue and eudaimonia are identical. According to another view, virtue serves as a means to eudaimonia (the "identical" and "sufficiency" theses, respectively).[119] Another point of debate is whether, according to Socrates, people desire what is in fact good—or, rather, simply what they perceive as good.[119]

Moral intellectualism refers to the prominent role Socrates gave to knowledge. He believed that all virtue was based on knowledge (hence Socrates is characterized as a virtue intellectualist). He also believed that humans were guided by the cognitive power to comprehend what they desire, while diminishing the role of impulses (a view termed motivational intellectualism).[120] In Plato's Protagoras (345c4–e6), Socrates implies that "no one errs willingly", which has become the hallmark of Socratic virtue intellectualism.[121] In Socratic moral philosophy, priority is given to the intellect as being the way to live a good life; Socrates deemphasizes irrational beliefs or passions.[122] Plato's dialogues that support Socrates's intellectual motivism—as this thesis is named—are mainly the Gorgias (467c–8e, where Socrates discusses the actions of a tyrant that do not benefit him) and Meno (77d–8b, where Socrates explains to Meno his view that no one wants bad things, unless they do not know what is good and bad in the first place).[123] Scholars have been puzzled by Socrates's view that akrasia (acting because of one's irrational passions, contrary to one's knowledge or beliefs) is impossible. Most believe that Socrates left no space for irrational desires, although some claim that Socrates acknowledged the existence of irrational motivations, but denied they play a primary role in decision-making.[124]

Religion

Socrates's religious nonconformity challenged the views of his times and his critique reshaped religious discourse for the coming centuries.[127] In Ancient Greece, organized religion was fragmented, celebrated in a number of festivals for specific gods, such as the City Dionysia, or in domestic rituals, and there were no sacred texts. Religion intermingled with the daily life of citizens, who performed their personal religious duties mainly with sacrifices to various gods.[128] Whether Socrates was a practicing man of religion or a 'provocateur atheist' has been a point of debate since ancient times; his trial included impiety accusations, and the controversy has not yet ceased.[129]

Socrates discusses divinity and the soul mostly in Alcibiades, Euthyphro, and Apology.[130] In Alcibiades Socrates links the human soul to divinity, concluding "Then this part of her resembles God, and whoever looks at this, and comes to know all that is divine, will gain thereby the best knowledge of himself."[131] His discussions on religion always fall under the lens of his rationalism.[132] Socrates, in Euthyphro, reaches a conclusion which takes him far from the age's usual practice: he considers sacrifices to the gods to be useless, especially when they are driven by the hope of receiving a reward in return. Instead, he calls for philosophy and the pursuit of knowledge to be the principal way of worshipping the gods.[133] His rejection of traditional forms of piety, connecting them to self-interest, implied that Athenians should seek religious experience by self-examination.[134]

Socrates argued that the gods were inherently wise and just, a perception far from traditional religion at that time.[135] In Euthyphro, the Euthyphro dilemma arises. Socrates questions his interlocutor about the relationship between piety and the will of a powerful god: Is something good because it is the will of this god, or is it the will of this god because it is good?[136] In other words, does piety follow the good, or the god? The trajectory of Socratic thought contrasts with traditional Greek theology, which took lex talionis (the eye for an eye principle) for granted. Socrates thought that goodness is independent from gods, and gods must themselves be pious.[137]

Socrates affirms a belief in gods in Plato's Apology, where he says to the jurors that he acknowledges gods more than his accusers.[138] For Plato's Socrates, the existence of gods is taken for granted; in none of his dialogues does he probe whether gods exist or not.[139] In Apology, a case for Socrates being agnostic can be made, based on his discussion of the great unknown after death,[140] and in Phaedo (the dialogue with his students in his last day) Socrates gives expression to a clear belief in the immortality of the soul.[141] He also believed in oracles, divinations and other messages from gods. These signs did not offer him any positive belief on moral issues; rather, they were predictions of unfavorable future events.[142]

In Xenophon's Memorabilia, Socrates constructs an argument close to the contemporary teleological intelligent-design argument. He claims that since there are many features in the universe that exhibit "signs of forethought" (e.g., eyelids), a divine creator must have created the universe.[139] He then deduces that the creator should be omniscient and omnipotent and also that it created the universe for the advance of humankind, since humans naturally have many abilities that other animals do not.[143] At times, Socrates speaks of a single deity, while at other times he refers to plural "gods". This has been interpreted to mean that he either believed that a supreme deity commanded other gods, or that various gods were parts, or manifestations, of this single deity.[144]

The relationship of Socrates's religious beliefs with his strict adherence to rationalism has been subject to debate.[145] Philosophy professor Mark McPherran suggests that Socrates interpreted every divine sign through secular rationality for confirmation.[146] Professor of ancient philosophy A. A. Long suggests that it is anachronistic to suppose that Socrates believed the religious and rational realms were separate.[147]

Socratic daimonion

In several texts (e.g., Plato's Euthyphro 3b5; Apology 31c–d; Xenophon's Memorabilia 1.1.2) Socrates claims he hears a daimōnic sign—an inner voice heard usually when he was about to make a mistake. Socrates gave a brief description of this daimonion at his trial (Apology 31c–d): "...The reason for this is something you have heard me frequently mention in different places—namely, the fact that I experience something divine and daimonic, as Meletus has inscribed in his indictment, by way of mockery. It started in my childhood, the occurrence of a particular voice. Whenever it occurs, it always deters me from the course of action I was intending to engage in, but it never gives me positive advice. It is this that has opposed my practicing politics, and I think its doing so has been absolutely fine."[149] Modern scholarship has variously interpreted this Socratic daimōnion as a rational source of knowledge, an impulse, a dream or even a paranormal experience felt by an ascetic Socrates.[150]

Virtue and knowledge

Socrates's theory of virtue states that all virtues are essentially one, since they are a form of knowledge.[151] For Socrates, the reason a person is not good is because they lack knowledge. Since knowledge is united, virtues are united as well. Another famous dictum—"no one errs willingly"—also derives from this theory.[152] In Protagoras, Socrates argues for the unity of virtues using the example of courage: if someone knows what the relevant danger is, they can undertake a risk.[151] Aristotle comments: " ... Socrates the elder thought that the end of life was knowledge of virtue, and he used to seek for the definition of justice, courage, and each of the parts of virtue, and this was a reasonable approach, since he thought that all virtues were sciences, and that as soon as one knew [for example] justice, he would be just..."[153]

Love

Some texts suggest that Socrates had love affairs with Alcibiades and other young persons; others suggest that Socrates's friendship with young boys sought only to improve them and were not sexual. In Gorgias, Socrates claims he was a dual lover of Alcibiades and philosophy, and his flirtatiousness is evident in Protagoras, Meno (76a–c) and Phaedrus (227c–d). However, the exact nature of his relationship with Alcibiades is not clear; Socrates was known for his self-restraint, while Alcibiades admits in the Symposium that he had tried to seduce Socrates but failed.[154]

The Socratic theory of love is mostly deduced from Lysis, where Socrates discusses love[155] at a wrestling school in the company of Lysis and his friends. They start their dialogue by investigating parental love and how it manifests with respect to the freedom and boundaries that parents set for their children. Socrates concludes that if Lysis is utterly useless, nobody will love him—not even his parents. While most scholars believe this text was intended to be humorous, it has also been suggested that Lysis shows Socrates held an egoistic view of love, according to which we only love people who are useful to us in some way.[156] Other scholars disagree with this view, arguing that Socrates's doctrine leaves room for non-egoistic love for a spouse; still others deny that Socrates suggests any egoistic motivation at all.[157] In Symposium, Socrates argues that children offer the false impression of immortality to their parents, and this misconception yields a form of unity among them.[158] Scholars also note that for Socrates, love is rational.[159]

Socrates, who claims to know only that he does not know, makes an exception (in Plato's Symposium), where he says he will tell the truth about Love, which he learned from a 'clever woman'. Classicist Armand D'Angour has made the case that Socrates was in his youth close to Aspasia, and that Diotima, to whom Socrates attributes his understanding of love in Symposium, is based on her;[160] however, it is also possible that Diotima really existed.

Socratic philosophy of politics

While Socrates was involved in public political and cultural debates, it is hard to define his exact political philosophy. In Plato's Gorgias, he tells Callicles: "I believe that I'm one of a few Athenians—so as not to say I'm the only one, but the only one among our contemporaries—to take up the true political craft and practice the true politics. This is because the speeches I make on each occasion do not aim at gratification but at what's best."[161] His claim illustrates his aversion for the established democratic assemblies and procedures such as voting—since Socrates saw politicians and rhetoricians as using tricks to mislead the public.[162] He never ran for office or suggested any legislation.[163] Rather, he aimed to help the city flourish by "improving" its citizens.[162] As a citizen, he abided by the law. He obeyed the rules and carried out his military duty by fighting wars abroad. His dialogues, however, make little mention of contemporary political decisions, such as the Sicilian Expedition.[163]

Socrates spent his time conversing with citizens, among them powerful members of Athenian society, scrutinizing their beliefs and bringing the contradictions of their ideas to light. Socrates believed he was doing them a favor since, for him, politics was about shaping the moral landscape of the city through philosophy rather than electoral procedures.[164] There is a debate over where Socrates stood in the polarized Athenian political climate, which was divided between oligarchs and democrats. While there is no clear textual evidence, one widely held theory holds that Socrates leaned towards democracy: he disobeyed the one order that the oligarchic government of the Thirty Tyrants gave him; he respected the laws and political system of Athens (which were formulated by democrats); and, according to this argument, his affinity for the ideals of democratic Athens was a reason why he did not want to escape prison and the death penalty. On the other hand, there is some evidence that Socrates leaned towards oligarchy: most of his friends supported oligarchy, he was contemptuous of the opinion of the many and was critical of the democratic process, and Protagoras shows some anti-democratic elements.[165] A less mainstream argument suggests that Socrates favoured democratic republicanism, a theory that prioritizes active participation in public life and concern for the city.[166]

Yet another suggestion is that Socrates endorsed views in line with liberalism, a political ideology formed in the Age of Enlightenment. This argument is mostly based on Crito and Apology, where Socrates talks about the mutually beneficial relationship between the city and its citizens. According to Socrates, citizens are morally autonomous and free to leave the city if they wish—but, by staying within the city, they also accept the laws and the city's authority over them.[167] On the other hand, Socrates has been seen as the first proponent of civil disobedience. Socrates's strong objection to injustice, along with his refusal to serve the Thirty Tyrants' order to arrest Leon, are suggestive of this line. As he says in Critias, "One ought never act unjustly, even to repay a wrong that has been done to oneself."[168] Ιn the broader picture, Socrates's advice would be for citizens to follow the orders of the state, unless, after much reflection, they deem them to be unjust.[169]

Legacy

Hellenistic era

Socrates's impact was immense in philosophy after his death. With the exception of the Epicureans and the Pyrrhonists, almost all philosophical currents after Socrates traced their roots to him: Plato's Academy, Aristotle's Lyceum, the Cynics, and the Stoics.[170] Interest in Socrates kept increasing until the third century AD.[171] The various schools differed in response to fundamental questions such as the purpose of life or the nature of arete (virtue), since Socrates had not handed them an answer, and therefore, philosophical schools subsequently diverged greatly in their interpretation of his thought.[172] He was considered to have shifted the focus of philosophy from a study of the natural world, as was the case for pre-Socratic philosophers, to a study of human affairs.[173]

Immediate followers of Socrates were his pupils, Euclid of Megara, Aristippus, and Antisthenes, who drew differing conclusions among themselves and followed independent trajectories.[174] The full doctrines of Socrates's pupils are difficult to reconstruct.[175] Antisthenes had a profound contempt of material goods. According to him, virtue was all that mattered. Diogenes and the Cynics continued this line of thought.[176] On the opposite end, Aristippus endorsed the accumulation of wealth and lived a luxurious life. After leaving Athens and returning to his home city of Cyrene, he founded the Cyrenaic philosophical school which was based on hedonism, and endorsing living an easy life with physical pleasures. His school passed to his grandson, bearing the same name. There is a dialogue in Xenophon's work in which Aristippus claims he wants to live without wishing to rule or be ruled by others.[177] In addition, Aristippus maintained a skeptical stance on epistemology, claiming that we can be certain only of our own feelings. This view resonates with the Socratic understanding of ignorance.[178] Euclid was a contemporary of Socrates. After Socrates's trial and death, he left Athens for the nearby town of Megara, where he founded a school, named the Megarians. His theory was built on the pre-Socratic monism of Parmenides. Euclid continued Socrates's thought, focusing on the nature of virtue.

The Stoics relied heavily on Socrates.[179] They applied the Socratic method as a tool to avoid inconsistencies. Their moral doctrines focused on how to live a smooth life through wisdom and virtue. The Stoics assigned virtue a crucial role in attaining happiness and also prioritized the relation between goodness and ethical excellence, all of which echoed Socratic thought.[180] At the same time, the philosophical current of Platonism claimed Socrates as its predecessor, in ethics and in its theory of knowledge. Arcesilaus, who became the head of the Academy about 80 years after its founding by Plato, radically changed the Academy's doctrine to what is now known as Academic Skepticism, centered on the Socratic philosophy of ignorance. The Academic Skeptics competed with the Stoics over who was Socrates's true heir with regard to ethics.[181] While the Stoics insisted on knowledge-based ethics, Arcesilaus relied on Socratic ignorance. The Stoics' reply to Arcesilaus was that Socratic ignorance was part of Socratic irony (they themselves disapproved the use of irony), an argument that ultimately became the dominant narrative of Socrates in later antiquity.[182]

While Aristotle considered Socrates an important philosopher, Socrates was not a central figure in Aristotelian thought. One of Aristotle's pupils, Aristoxenus even authored a book detailing Socrates's scandals.

The Epicureans were antagonistic to Socrates.[183] They attacked him for superstition, criticizing his belief in his daimonion and his regard for the oracle at Delphi.[184] They also criticized Socrates for his character and various faults, and focusing mostly on his irony, which was deemed inappropriate for a philosopher and unseemly for a teacher.[185]

The Pyrrhonists were also antagonistic to Socrates, accusing him of being a prater about ethics, who engaged in mock humility, and who sneered at and mocked people.[186]

Medieval world

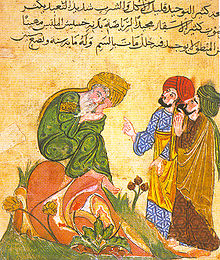

Socratic thought found its way to the Islamic Middle East alongside that of Aristotle and the Stoics. Plato's works on Socrates, as well as other ancient Greek literature, were translated into Arabic by early Muslim scholars such as Al-Kindi, Jabir ibn Hayyan, and the Muʿtazila. For Muslim scholars, Socrates was hailed and admired for combining his ethics with his lifestyle, perhaps because of the resemblance in this regard with Muhammad's personality.[187] Socratic doctrines were altered to match Islamic faith: according to Muslim scholars, Socrates made arguments for monotheism and for the temporality of this world and rewards in the next life.[188] His influence in the Arabic-speaking world continues to the present day.[189]

In medieval times, little of Socrates's thought survived in the Christian world as a whole; however, works on Socrates from Christian scholars such as Lactantius, Eusebius and Augustine were maintained in the Byzantine Empire, where Socrates was studied under a Christian lens.[190] After the fall of Constantinople, many of the texts were brought back into the world of Roman Christianity, where they were translated into Latin. Overall, ancient Socratic philosophy, like the rest of classical literature before the Renaissance, was addressed with skepticism in the Christian world at first.[191]

During the early Italian Renaissance, two different narratives of Socrates developed.[192] On the one hand, the humanist movement revived interest in classical authors. Leonardo Bruni translated many of Plato's Socratic dialogues, while his pupil Giannozzo Manetti authored a well-circulated book, a Life of Socrates. They both presented a civic version of Socrates, according to which Socrates was a humanist and a supporter of republicanism. Bruni and Manetti were interested in defending secularism as a non-sinful way of life; presenting a view of Socrates that was aligned with Christian morality assisted their cause. In doing so, they had to censor parts of his dialogues, especially those which appeared to promote homosexuality or any possibility of pederasty (with Alcibiades), or which suggested that the Socratic daimon was a god.[193] On the other hand, a different picture of Socrates was presented by Italian Neoplatonists, led by the philosopher and priest Marsilio Ficino. Ficino was impressed by Socrates's un-hierarchical and informal way teaching, which he tried to replicate. Ficino portrayed a holy picture of Socrates, finding parallels with the life of Jesus Christ. For Ficino and his followers, Socratic ignorance signified his acknowledgement that all wisdom is God-given (through the Socratic daimon).[194]

Modern times

In early modern France, Socrates's image was dominated by features of his private life rather than his philosophical thought, in various novels and satirical plays.[196] Some thinkers used Socrates to highlight and comment upon controversies of their own era, like Théophile de Viau who portrayed a Christianized Socrates accused of atheism,[197] while for Voltaire, the figure of Socrates represented a reason-based theist.[198] Michel de Montaigne wrote extensively on Socrates, linking him to rationalism as a counterweight to contemporary religious fanatics.[199]

In the 18th century, German idealism revived philosophical interest in Socrates, mainly through Hegel's work. For Hegel, Socrates marked a turning point in the history of humankind by the introduction of the principle of free subjectivity or self-determination. While Hegel hails Socrates for his contribution, he nonetheless justifies the Athenian court, for Socrates's insistence upon self-determination would be destructive of the Sittlichkeit (a Hegelian term signifying the way of life as shaped by the institutions and laws of the State).[200] Also, Hegel sees the Socratic use of rationalism as a continuation of Protagoras' focus on human reasoning (as encapsulated in the motto homo mensura: "man is the measure of all things"), but modified: it is our reasoning that can help us reach objective conclusions about reality.[201] Also, Hegel considered Socrates as a predecessor of later ancient skeptic philosophers, even though he never clearly explained why.[202]

Søren Kierkegaard considered Socrates his teacher,[203] and authored his master's thesis on him, The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates.[204] There he argues that Socrates is not a moral philosopher but is purely an ironist.[205] He also focused on Socrates's avoidance of writing: for Kierkegaard, this avoidance was a sign of humility, deriving from Socrates's acceptance of his ignorance.[206] Not only did Socrates not write anything down, according to Kierkegaard, but his contemporaries misconstrued and misunderstood him as a philosopher, leaving us with an almost impossible task in comprehending Socratic thought.[204] Only Plato's Apology was close to the real Socrates, in Kierkegaard's view.[207] In his writings, he revisited Socrates quite frequently; in his later work, Kierkegaard found ethical elements in Socratic thought.[205] Socrates was not only a subject of study for Kierkegaard, he was a model as well: Kierkegaard paralleled his task as a philosopher to Socrates. He writes, "The only analogy I have before me is Socrates; my task is a Socratic task, to audit the definition of what it is to be a Christian", with his aim being to bring society closer to the Christian ideal, since he believed that Christianity had become a formality, void of any Christian essence.[208] Kierkegaard denied being a Christian, as Socrates denied possessing any knowledge.[209]

Friedrich Nietzsche resented Socrates's contributions to Western culture.[210] In his first book, The Birth of Tragedy (1872), Nietzsche held Socrates responsible for what he saw as the deterioration of ancient Greek civilization during the 4th century BC and after. For Nietzsche, Socrates turned the scope of philosophy from pre-Socratic naturalism to rationalism and intellectualism. He writes: "I conceive of [the Presocratics] as precursors to a reformation of the Greeks: but not of Socrates"; "with Empedocles and Democritus the Greeks were well on their way towards taking the correct measure of human existence, its unreason, its suffering; they never reached this goal, thanks to Socrates".[211] The effect, Nietzsche proposed, was a perverse situation that had continued down to his day: our culture is a Socratic culture, he believed.[210] In a later publication, The Twilight of the Idols (1887), Nietzsche continued his offensive against Socrates, focusing on the arbitrary linking of reason to virtue and happiness in Socratic thinking. He writes: "I try to understand from what partial and idiosyncratic states the Socratic problem is to be derived: his equation of reason = virtue = happiness. It was with this absurdity of a doctrine of identity that he fascinated: ancient philosophy never again freed itself [from this fascination]".[212] From the late 19th century until the early 20th, the most common explanation of Nietzsche's hostility towards Socrates was his anti-rationalism; he considered Socrates the father of European rationalism. In the mid-20th century, philosopher Walter Kaufmann published an article arguing that Nietzsche admired Socrates. Current mainstream opinion is that Nietzsche was ambivalent towards Socrates.[213]

Continental philosophers Hannah Arendt, Leo Strauss and Karl Popper, after experiencing the horrors of World War II, amidst the rise of totalitarian regimes, saw Socrates as an icon of individual conscience.[214] Arendt, in Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), suggests that Socrates's constant questioning and self-reflection could prevent the banality of evil.[215] Strauss considers Socrates's political thought as paralleling Plato's. He sees an elitist Socrates in Plato's Republic as exemplifying why the polis is not, and could not be, an ideal way of organizing life, since philosophical truths cannot be digested by the masses.[216] Popper takes the opposite view: he argues that Socrates opposes Plato's totalitarian ideas. For Popper, Socratic individualism, along with Athenian democracy, imply Popper's concept of the "open society" as described in his Open Society and Its Enemies (1945).[217]

See also

- Codex Vaticanus Graecus 64 - Socratic Letters

- De genio Socratis

- List of cultural depictions of Socrates

- List of speakers in Plato's dialogues

Notes

- ^ Amy C. Smith (2003), “Athenian Political Art from the fifth and fourth centuries BCE: Images of Historical Individuals,” p. 14, in C.W. Blackwell, ed., Dēmos: Classical Athenian Democracy. The Stoa: a consortium for electronic publication in the humanities.

- ^ Jones 2006.

- ^ "Socrates (469—399 B.C.E.)". Internet encyclopedia of philosophy. Retrieved 27 August 2024.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 5–7; Dorion 2011, pp. 1–2; May 2000, p. 9; Waterfield 2013, p. 1.

- ^ May 2000, p. 20; Dorion 2011, p. 7; Waterfield 2013, p. 1.

- ^ Döring 2011, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Dorion 2011, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 13–15.

- ^ a b c Guthrie 1972, p. 15.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 15–16, 28.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 18.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 29–31; Dorion 2011, p. 6.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 30.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 29–33; Waterfield 2013, pp. 3–4.

- ^ May 2000, p. 20; Dorion 2011, pp. 6–7.

- ^ May 2000, p. 20; Waterfield 2013, pp. 3–4.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Dorion 2011, pp. 4, 10.

- ^ Waterfield 2013, pp. 10–13.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 39–51.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, p. 5.

- ^ Konstan 2011, pp. 85, 88.

- ^ Waterfield 2013, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Vlastos 1991, p. 52; Kahn 1998, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 35–36; Waterfield 2013, p. 8.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 38.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Dorion 2011, pp. 11, 16; Waterfield 2013, p. 11.

- ^ Waterfield 2013, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Waterfield 2013, p. 11.

- ^ Dorion 2011, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Dorion 2011, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Dorion 2011, p. 5.

- ^ Dorion 2011, pp. 7–10.

- ^ a b Dorion 2011, pp. 12–14.

- ^ Dorion 2011, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 2.

- ^ Ober 2010, pp. 159–160; Ahbel-Rappe 2011, p. 1; Guthrie 1972, p. 58; Dorion 2011, p. 12; Nails 2020, A chronology of the historical Socrates in the context of Athenian history and the dramatic dates of Plato's dialogues.

- ^ Ober 2010, pp. 160–161.

- ^ Ober 2010, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Ober 2010, p. 161.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 65.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 59.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 65; Ober 2010, pp. 167–171.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 78.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Guthrie 1972, p. 69.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 70–75; Nails 2020, Socrates's strangeness.

- ^ Obdrzalek 2013, pp. 210–211; Nails 2020, Socrates's strangeness.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 92–94; Nails 2020, Socrates's strangeness.

- ^ Kahn 1998, p. 75.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, pp. 15–19.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, pp. 17, 21.

- ^ Plato. "Phaedo". Perseus. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

See §118a

- ^ May 2000, p. 30, 40.

- ^ a b c d May 2000, pp. 47–48.

- ^ a b c d e f Nails 2020, A Chronology of the historical Socrates.

- ^ May 2000, p. 31.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 33–39.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 41–42.

- ^ May 2000, p. 42.

- ^ May 2000, p. 43.

- ^ May 2000, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 63–65; Ahbel-Rappe 2011; Ober 2010, p. 146.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 64–65.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 20, 65–66; Ober 2010, p. 146.

- ^ a b Ralkowski 2013, p. 302.

- ^ Ralkowski 2013, p. 323.

- ^ Ralkowski 2013, pp. 319–322.

- ^ Ralkowski 2013, pp. 307–308.

- ^ Ralkowski 2013, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, p. 53.

- ^ Benson 2011, p. 179; Wolfsdorf 2013, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Wolfsdorf 2013, p. 34: Others include Charmides, Crito, Euthydemus, Euthyphro, Hippias Major, Hippias Minor, Ion, Laches, Lysis, Protagoras. Benson 2011, p. 179, also adds parts of Meno.

- ^ Benson 2011, pp. 182–184; Wolfsdorf 2013, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Benson 2011, p. 184.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 125–127.

- ^ a b Guthrie 1972, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Benson 2011, pp. 179, 185–193.

- ^ Benson 2011, p. 185; Wolfsdorf 2013, pp. 34–35; Ambury 2020, The Elenchus: Socrates the Refuter.

- ^ Benson 2011, p. 185; Wolfsdorf 2013, p. 44; Ambury 2020, The Elenchus: Socrates the Refuter.

- ^ Benson 2011, p. 185.

- ^ Ambury 2020, The Elenchus: Socrates the Refuter: Benson (2011) names in a note scholars that are of constructivist and non-constructivism approach: "Among those "constructivists" willing to do so are Brickhouse and Smith 1994, ch. 6.1; Burnet 1924, pp. 136–137; McPherran 1985; Rabinowitz 1958; Reeve 1989, ch. 1.10; Taylor 1982; and Vlastos 1991, ch. 6. Those who do not think a Socratic account of piety is implied by the text ("anticonstructivists") include Allen 1970, pp. 6–9, 67; and Grote 1865, pp. 437–457. Beckman 1979, ch. 2.1; Calef 1995; and Versényi 1982" p.118

- ^ Benson 2013, p. 136.

- ^ Benson 2013, pp. 136–139; Ahbel-Rappe 2011, p. 71.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 112.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Benson 2013, pp. 143–145; Bett 2011, p. 228.

- ^ Benson 2013, pp. 143–145, 147; Bett 2011, p. 229.

- ^ Benson 2013, p. 145.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, p. 144.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 122; Bett 2011, p. 215; McPartland 2013, pp. 94–95.

- ^ McPartland 2013, p. 98.

- ^ McPartland 2013, pp. 108–109.

- ^ McPartland 2013, p. 117.

- ^ McPartland 2013, p. 119.

- ^ McPartland 2013, pp. 117–119.

- ^ McPartland 2013, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Vlastos 1985, p. 1.

- ^ a b Vlastos 1985, pp. 6–7.

- ^ Vlastos 1985, pp. 1–2; Lesher 1987, p. 275.

- ^ Lesher 1987, p. 276.

- ^ Lesher 1987, p. 276; Vasiliou 2013, p. 28.

- ^ Lesher 1987, p. 278; McPartland 2013, p. 123.

- ^ McPartland 2013, pp. 123–124.

- ^ Lane 2011, p. 239.

- ^ Vasiliou 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Vasiliou 2013, p. 24; Lane 2011, p. 239.

- ^ Lane 2011, pp. 249–251.

- ^ Lane 2011, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Lane 2011, p. 243.

- ^ Vasiliou 2013, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Brickhouse & Smith 2013, p. 185; Vlastos 1991, p. 203.

- ^ a b Reshotko 2013, p. 158.

- ^ Brickhouse & Smith 2013, p. 185.

- ^ Segvic 2006, pp. 171–173.

- ^ Segvic 2006, p. 171.

- ^ Brickhouse & Smith 2013, pp. 185–186.

- ^ Brickhouse & Smith 2013, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Ausland 2019, pp. 686–687.

- ^ McPherran 2011, p. 117.

- ^ McPherran 2013, p. 257.

- ^ McPherran 2013, pp. 259–260.

- ^ McPherran 2013, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 153.

- ^ McPherran 2013, pp. 260–262; McPherran 2011, p. 111.

- ^ McPherran 2013, p. 265.

- ^ McPherran 2013, p. 266.

- ^ McPherran 2013, pp. 263–266.

- ^ McPherran 2013, p. 263:See also note 30 for further reference; McPherran 2011, p. 117.

- ^ McPherran 2011, pp. 117–119.

- ^ McPherran 2013, pp. 272–273.

- ^ a b McPherran 2013, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 160–164.

- ^ McPherran 2011, pp. 123–127.

- ^ McPherran 2013, pp. 270–271; Long 2009, p. 63.

- ^ McPherran 2013, p. 272; Long 2009, p. 63.

- ^ McPherran 2011, pp. 114–115.

- ^ McPherran 2011, p. 124.

- ^ Long 2009, p. 64.

- ^ Lapatin 2009, p. 146.

- ^ Long 2009, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Long 2009, pp. 65–66, 70.

- ^ a b Guthrie 1972, p. 131.

- ^ Rowe 2006, pp. 164–165.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 131; Ahbel-Rappe & Kamtekar 2009, p. 72.

- ^ Obdrzalek 2013, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Obdrzalek 2013, pp. 211–212; Rudebusch 2009, p. 187.

- ^ Obdrzalek 2013, pp. 214–215.

- ^ Obdrzalek 2013, p. 212.

- ^ Obdrzalek 2013, p. 231.

- ^ Obdrzalek 2013, p. 230.

- ^ D'Angour 2019.

- ^ Griswold 2011, pp. 333–341; Johnson 2013, p. 234.

- ^ a b Johnson 2013, p. 234.

- ^ a b Griswold 2011, p. 334.

- ^ Johnson 2013, p. 235.

- ^ Johnson 2013, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Johnson 2013, p. 238.

- ^ Johnson 2013, pp. 239–241.

- ^ Johnson 2013, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Johnson 2013, pp. 255–256.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 99, 165; Long 2011, p. 355; Ahbel-Rappe 2011, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Long 2011, pp. 355–356.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 165–166; Long 2011, pp. 355–357.

- ^ Long 2011, p. 358.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 169.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 179–183.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, p. 170.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 170–174.

- ^ Guthrie 1972, pp. 175–177.

- ^ Long 2011, p. 362.

- ^ Long 2011, pp. 362–264.

- ^ Long 2011, pp. 364–365.

- ^ Long 2011, p. 367.

- ^ Long 2011, pp. 368–369.

- ^ Long 2011, p. 374.

- ^ Campos-Daroca 2019, p. 240; Lane 2011, p. 244; Long 2011, p. 370.

- ^ "Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers Book II, Chapter 5, Section 19". Archived from the original on 24 January 2022. Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ Alon 2009, pp. 317–318.

- ^ Alon 2009, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Alon 2009, p. 332.

- ^ Trizio 2019, pp. 609–610; Hankins 2009, p. 352.

- ^ Hankins 2009, pp. 337–340.

- ^ Hankins 2009, pp. 348–349.

- ^ Hankins 2009, pp. 341–346.

- ^ Hankins 2009, pp. 346–348.

- ^ Lapatin 2009, pp. 133–139.

- ^ McLean 2009, pp. 353–354.

- ^ McLean 2009, p. 355.

- ^ Loughlin 2019, p. 665.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, p. 12.

- ^ Bowman 2019, pp. 751–753.

- ^ Bowman 2019, pp. 753, 761–763.

- ^ White 2009, pp. 373–374.

- ^ Schur & Yamato 2019, p. 820.

- ^ a b Schur & Yamato 2019, p. 824.

- ^ a b Muench 2009, p. 389.

- ^ Schur & Yamato 2019, pp. 824–825.

- ^ Muench 2009, p. 390.

- ^ Muench 2009, pp. 390–391:Quote from Kierkegaard's essay My Task (1855)

- ^ Muench 2009, p. 394.

- ^ a b Raymond 2019, p. 837.

- ^ Porter 2009, pp. 408–409; Ambury 2020, Legacy: How Have Other Philosophers Understood Socrates?.

- ^ Porter 2009, pp. 410–411.

- ^ Raymond 2019, pp. 837–839.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, p. 127.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, pp. 138–140.

- ^ Ahbel-Rappe 2011, pp. 140–142.

Sources

- Ahbel-Rappe, Sara; Kamtekar, Rachana (2009). A Companion to Socrates. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Ahbel-Rappe, Sara (2011). Socrates: A Guide for the Perplexed. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-8264-3325-1.

- Alon, Ilai (2009). "Socrates in Arabic Philosophy". In Ahbel-Rappe, Sara; Kamtekar, Rachana (eds.). A Companion to Socrates. Wiley. pp. 313–326. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch20. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Ambury, James M. (2020). "Socrates". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Ausland, Hayden W. (2019). "Socrates in the Early Nineteenth Century, Become Young and Beautiful". In Kyriakos N. Demetriou (ed.). Brill's Companion to the Reception of Socrates. Brill. pp. 685–718. ISBN 978-90-04-39675-3.

- Benson, Hugh H. (2011). "Socratic Method". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 179–200. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.008. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- Benson, Hugh H. (2013). "The priority of definition". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 136–155. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2.

- Bett, Richard (2011). "Socratic Ignorance". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 215–236. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.010. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- Bowman, Brady (2019). "Hegel on Socrates and the Historical Advent of Moral Self-Consciousness". In Kyriakos N. Demetriou (ed.). Brill's Companion to the Reception of Socrates. Brill. pp. 749–792. doi:10.1163/9789004396753_030. ISBN 978-90-04-39675-3. S2CID 181666253.

- Brickhouse, Thomas C.; Smith, Nicholas D. (2013). "Socratic Moral Psychology". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 185–209. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2.

- Campos-Daroca, F. Javier (2019). "Epicurus and the Epicureans on Socrates and the Socratics". In Moore, Christopher (ed.). Brill's Companion to the Reception of Socrates. Brill Publishers. pp. 237–265. doi:10.1163/9789004396753_010. ISBN 978-90-04-39675-3. S2CID 182098719.

- D'Angour, Armand (2019). Socrates in Love. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-14-08-88391-4. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 6 March 2022.

- Döring, Klaus (2011). "The Students of Socrates". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 24–47. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.002. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- Dorion, Louis André (2011). "The Rise and Fall of the Socratic Problem". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–23. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.001. hdl:10795/1977. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- Guthrie, W. K. C. (1972). A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 3, The Fifth Century Enlightenment, Part 2, Socrates. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511518454. ISBN 978-0-521-09667-6.

- Griswold, Charles L. (2011). "Socrates' Political Philosophy". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 333–352. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.014. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- Hankins, James (2009). "Socrates in the Italian Renaissance". In Ahbel-Rappe, Sara; Kamtekar, Rachana (eds.). A Companion to Socrates. Wiley. pp. 337–352. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch21. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Johnson, Curtis (2013). "Socrates' political philosophy". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 233–256. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2.

- Jones, Daniel (2006). English Pronouncing Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68086-8.

- Kahn, Charles H. (1998). Plato and the Socratic Dialogue: The Philosophical Use of a Literary Form. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511585579. ISBN 978-0-521-64830-1.

- Konstan, David (2011). "Socrates in Aristophanes' Clouds". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 75–90. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.004. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- Lane, Melissa (2011). "Reconsidering Socratic Irony". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 237–259. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.011. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- Lapatin, Keneth (2009). "Picturing Socrates". In Sara Ahbel-Rappe (ed.). A Companion to Socrates. Rachana Kamtekar. Wiley. pp. 110–155. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Lesher, J. H. (James H.) (1987). "Socrates' Disavowal of Knowledge". Journal of the History of Philosophy. 25 (2). Project Muse: 275–288. doi:10.1353/hph.1987.0033. ISSN 1538-4586. S2CID 171007876. Archived from the original on 20 February 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- Long, A.A. (2009). "How Does Socrates' Divine Sign Communicate with Him?". In Sara Ahbel-Rappe (ed.). A Companion to Socrates. Rachana Kamtekar. Wiley. pp. 63–74. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch5. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Long, A.A. (2011). "Socrates in Later Greek Philosophy". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 355–379. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.015. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- Loughlin, Felicity P. (2019). "Socrates and Religious Debate in the Scottish Enlightenment". In Kyriakos N. Demetriou (ed.). Brill's Companion to the Reception of Socrates. Brill. pp. 658–683. doi:10.1163/9789004396753_027. ISBN 978-90-04-39675-3. S2CID 182644665.

- May, Hope (2000). On Socrates. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. ISBN 978-0-534-57604-2.

- McPherran, Mark L. (2011). "Socratic religion". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–127. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.006. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- McPherran, Mark L. (2013). "Socratic theology and piety". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 257–277. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2.

- McPartland, Keith (2013). "Socratic Ignorance and Types of Knowledge". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 94–135. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2.

- McLean, Daniel R. (2009). "The Private Life of Socrates in Early Modern France". In Ahbel-Rappe, Sara; Kamtekar, Rachana (eds.). A Companion to Socrates. Wiley. pp. 353–367. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch22. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Muench, Paul (2009). "Kierkegaard's Socratic Point of View". In Sara Ahbel-Rappe (ed.). A Companion to Socrates. Rachana Kamtekar. Wiley. pp. 389–405. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch24. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Nails, Debra (2020). Edward N. Zalta (ed.). "Socrates". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- Ober, Josiah (2010). "Socrates and Democratic Athens". In Donald R. Morrison (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Socrates. Cambridge University Press. pp. 138–178. doi:10.1017/CCOL9780521833424.007. ISBN 978-0-521-83342-4.

- Obdrzalek, Suzanne (2013). "Socrates on Love". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 210–232. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2.

- Porter, James I. (2009). "Nietzsche and 'The Problem of Socrates'". In Sara Ahbel-Rappe (ed.). A Companion to Socrates. Rachana Kamtekar. Wiley. pp. 406–425. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch25. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Ralkowski, Mark (2013). "The politics of impiety why was Socrates prosecuted by the Athenian democracy ?". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 301–327. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2.

- Raymond, Christopher C. (2019). "Nietzsche's Revaluation of Socrates". In Kyriakos N. Demetriou (ed.). Brill's Companion to the Reception of Socrates. Brill. pp. 837–683. doi:10.1163/9789004396753_033. ISBN 978-90-04-39675-3. S2CID 182444038.

- Reshotko, Naomi (2013). "Socratic eudaimonism". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 156–184. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2.

- Rowe, Christopher (2006). "Socrates in Plato's Dialogues". In Sara Ahbel-Rappe (ed.). A Companion to Socrates. Rachana Kamtekar. Wiley. pp. 159–170. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch10. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Rudebusch, George (2009). "Socratic Love". In Sara Ahbel-Rappe (ed.). A Companion to Socrates. Rachana Kamtekar. Wiley. pp. 186–199. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch11. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Segvic, Heda (2006). "No One Errs Willingly: The Meaning of Socratic Intellectualism". In Sara Ahbel-Rappe (ed.). A Companion to Socrates. Rachana Kamtekar. Wiley. pp. 171–185. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch10. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1.

- Schur, David; Yamato, Lori (2019). "Kierkegaard's Socratic Way of Writing". In Kyriakos N. Demetriou (ed.). Brill's Companion to the Reception of Socrates. Brill Publishers. pp. 820–836. doi:10.1163/9789004396753_032. ISBN 978-90-04-39675-3. S2CID 181535294. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- Trizio, Michele (2019). "Socrates in Byzantium". In Moore, Christopher (ed.). Brill's Companion to the Reception of Socrates. Brill Publishers. pp. 592–618. doi:10.1163/9789004396753_024. ISBN 978-90-04-39675-3. S2CID 182037431. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- Vasiliou, Iakovos (2013). "Socratic irony". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 20–33. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- Vlastos, Gregory (1985). "Socrates' Disavowal of Knowledge". The Philosophical Quarterly. 35 (138). Oxford University Press (OUP): 1–31. doi:10.2307/2219545. ISSN 0031-8094. JSTOR 2219545.

- Vlastos, Gregory (1991). Socrates, Ironist and Moral Philosopher. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9787-2.

- Waterfield, Robin (2013). "Quest for the historical Socrates". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 1–19. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- Wolfsdorf, David (2013). "Quest for the historical Socrates". In Nicholas D. Smith (ed.). The Bloomsbury Companion to Socrates. John Bussanich. A&C Black. pp. 34–67. ISBN 978-1-4411-1284-2. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 1 June 2021.

- White, Nicholas (2009). "Socrates in Hegel and Others". In Sara Ahbel-Rappe (ed.). A Companion to Socrates. Rachana Kamtekar. Wiley. pp. 368–387. doi:10.1002/9780470996218.ch23. ISBN 978-1-4051-5458-1. Archived from the original on 29 February 2024. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

Further reading

- Brun, Jean (1978). Socrate (in French) (6th ed.). Presses universitaires de France. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-2-13-035620-2.

- Benson, Hugh (1992). Essays on the philosophy of Socrates. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506757-6. OCLC 23179683.

- Rudebusch, George (2009). Socrates. Chichester, UK; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5085-9. OCLC 476311710.

- Taylor, C. C. W. (1998). Socrates. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-287601-0.

- Taylor, C. C. W. (2019). Socrates: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-883598-1.

- Vlastos, Gregory (1994). Socratic Studies. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44735-5.

External links

- Socrates

- 5th-century BC Athenians

- 5th-century BC Greek philosophers

- 4th-century BC executions

- 470s BC births

- 399 BC deaths

- Ancient Athenian philosophers

- Ancient Greek epistemologists

- Ancient Greek ethicists

- Ancient Greek philosophers of mind

- Ancient Greek political philosophers

- Ancient Greeks accused of sacrilege

- Critics of religions

- Executed ancient Greek people

- Executed philosophers

- Family of Socrates

- Forced suicides

- Irony theorists

- People executed by ancient Athens

- People executed by poison

- People executed for heresy

- Philosophers of education

- Philosophers of love

- Classical theism