USS Aroostook (CM-3)

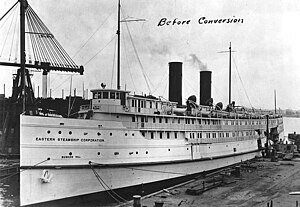

Bunker Hill with the passenger superstructure that was added in 1911

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Namesake |

|

| Owner |

|

| Operator | 1917: United States Navy |

| Port of registry |

|

| Route |

|

| Builder | Wm Cramp & Sons, Philadelphia |

| Yard number | 343 |

| Launched | 26 March 1907 |

| Sponsored by | Rose Fitzgerald |

| Completed | 1907 |

| Acquired | for US Navy, 12 November 1917 |

| Commissioned | 7 December 1917 |

| Decommissioned | 10 March 1931 |

| Maiden voyage | 11 July 1907 |

| Refit | 1911; 1917; 1919 |

| Stricken | 5 February 1943 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Scrapped, 1947 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type |

|

| Tonnage | |

| Displacement | 1918: 3,800 long tons (3,900 t) |

| Length | |

| Beam | 52.2 ft (15.9 m) |

| Draft | 16 ft 0 in (4.88 m) |

| Depth |

|

| Decks | 2 |

| Installed power | 674 NHP; 7,500 ihp |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 20 knots (37 km/h) |

| Capacity |

|

| Complement | in US Navy, 313 |

| Crew |

|

| Armament | |

USS Aroostook (ID-1256 / CM-3 / AK-44) was a steamship that was built as the coastal cargo liner Bunker Hill. She was launched in 1907 by Rose Fitzgerald, who in 1914 became Rose Kennedy. In 1911 Bunker Hill was refitted as a passenger ship. She ran between Boston and New York until 1917, when the United States Navy commissioned her as USS Aroostook, and converted her into a minelayer. In 1918 she took part in laying the North Sea Mine Barrage.

In 1919 Aroostook was converted into a flying boat tender, and supported the US Navy's successful attempt to fly a flying boat from North America to Europe. In 1925 she supported the Navy's unsuccessful attempt to fly a flying boat from California to Hawaii, and led the search for the aircraft after it had to touch down in mid-ocean. In 1931 she was decommissioned and placed in the reserve fleet.

In 1941 the Navy tried to convert Aroostook back into a cargo ship, but found it impractical due to her age. She was stricken from the Naval Register in 1943, and her name was reverted to Bunker Hill. In 1946 the former boot-legger Anthony Cornero bought her, renamed her Lux, and had her converted into a gambling ship. The United States Coast Guard seized her, and in 1947 she was scrapped.

Cargo ship

[edit]In 1907 William Cramp & Sons of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania built three cargo ships for the New England Navigation Company, which was a subsidiary of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad to compete with the Metropolitan Line ships Yale and Harvard between Boston and New York. The Quintard Iron Works Company of New York designed the three ships to have enough freeboard and structural strength to operate offshore in the North Atlantic, but also be able to fit into the ports of New Haven, New London, Providence, Fall River, and New Bedford. They were designed as cargo ships, but also had four cabins for passengers. Each ship carried four lifeboats, and was designed to be equipped with wireless telegraphy.[1]

Yard number 343 was launched on 29 January 1907 as Massachusetts.[2] The New England Navigation Company planned to call yard number 344 Commonwealth. However, John F. Fitzgerald, Mayor of Boston, proposed that his 16-year-old daughter Rose launch the ship, on condition that the company change the name to commemorate the 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill in the Siege of Boston. The company agreed, and on 26 March 1907 Rose Fitzgerald launched her as Bunker Hill.[3]

Bunker Hill's lengths were 395 ft (120 m) overall[4] and 375 ft (114 m) between perpendiculars. Her beam was 52.2 ft (15.9 m) and her depth was 31.6 ft (9.6 m).[5][6] Her main deck could carry 1,500 tons of cargo.[1][7] Cargo was loaded and unloaded via doors in each side of the ship (see 1908 photo). Her tonnages were 4,029 GRT and 1,724 NRT.[5][6]

Like her sister ship Massachusetts, she had twin screws, each driven by a four-cylinder triple-expansion engine. The combined power of her twin engines was rated at 674 NHP[6] or 7,500 ihp,[3][7] which gave her a speed of 20 knots (37 km/h). This made Massachusetts and Bunker Hill the swiftest cargo ships on the coastal route between Boston and New York.[8] Cramp completed Massachusetts in April 1907, and Bunker Hill that June.[9]

Bunker Hill was registered in New London. Her US official number was 204264 and her code letters were KWDT.[6] On her maiden voyage, on 11 July 1907, she steamed along Long Island Sound from New York to Fall River in seven and a half hours. This set a new record, and won her the title of "Queen of the Sound".[10]

Cramp built a third ship, yard number 345. She was launched as Old Colony; completed in September 1907;[9] and entered service that November.[11] She differed from her two sisters by having three screws instead of two, driven by Parsons turbines instead of reciprocating engines.[12]

The three sister ships soon achieved the New Haven Railroad's aim to monopolise the sea route between Boston and New York. In November 1907 the New England Navigation Company announced that from January 1908 the three ships would start a direct cargo service between Boston and New York, at prices about 25 percent less than was currently in force. The voyage would take about 24 hours; sailings would be three times a week; and they could be increased to daily if there was enough demand.[13] The service would run via the "outside route", i.e. the seaward side of Long Island, instead of through Long Island Sound.[8] That December their competitors, Yale and Harvard, were laid up. At the same time, the New Haven laid off up to 4,000 railroad workers.[14] The first sailing on the new route was by Bunker Hill, which left Boston at 17:00 hrs on 4 January 1908. Departures from Boston were to be each Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday.[15][16]

Sinking of Transfer No. 3

[edit]On 2 October 1907 Bunker Hill was in New York harbor. At about 06:20 hrs that morning a New Haven Railroad tugboat, Transfer No. 3, was coming around the cargo ship's stern to reach her port side. As she did so, Bunker Hill started her starboard engine. The propeller struck the tugboat's port side, holing its hull, and sinking it. There were no casualties.[17]

Passenger ship

[edit]In 1911 the Maine Steamship Company acquired Massachusetts, Bunker Hill, and Old Colony, and registered them in Portland, Maine. It contracted the Quintard Iron Works to refit them as passenger ships, at a cost of $500,000 each. On each ship, Quintard built up the forecastle, extended the superstructure aft, and added another deck the full length of the superstructure. According to reports in 1911, Quintard had designed the ships to be enlarged in this way. The new accommodation included 225 passenger cabins; a dining saloon in the forward part; a grill room; a "social hall" that was also a smoking room and café; and a hurricane deck with an observation room. For freight, there were four elevators that linked the main deck with the hold below. Each ship had a double hull, divided by six watertight bulkheads. The Maine SS Co named its Boston – New York service "The Boston Line".[18] The refit increased their gross register tonnage; in Bunker Hill's case from 4,029 GRT to 4,779 GRT.[19][20] Conversion to passenger service increased her crew from 38 officers and men to 167.[21]

Collision with Massachusetts

[edit]

By June 1912 the Eastern Steamship Corporation had acquired the three ships, and registered them in Boston.[20] Eastern kept the ships on the Boston – New York route, which it called the "Metropolitan Line". At 01:30 hrs on 7 July that year, Massachusetts accidentally rammed Bunker Hill in fog off Point Judith, Rhode Island. Massachusetts was going dead slow, and heard Bunker Hill give a fog signal on her steam whistle. Both ships stopped engines, but too late to prevent a collision. The impact made a hole 50 feet (15 m) wide and 12 feet (3.7 m) high in Bunker Hill's side, and slightly dented Massachusetts' bow, but both ships remained afloat. Two of Bunker Hill's passengers suffered cuts and bruises. Massachusetts continued her voyage to New York. Bunker Hill continued her voyage to Boston; disembarked her passengers; and then headed for Erie Basin, Brooklyn to be repaired.[22][23]

By 1913, Bunker Hill's wireless call sign was KJB.[24]

Collision with Vanadis

[edit]

On 13 June 1915, C. K. G. Billings' steam yacht Vanadis accidentally rammed Bunker Hill in dense fog off Eaton's Neck in Long Island Sound. Bunker Hill was on her scheduled run from New York to Boston, carrying about 250 passengers and 130 crew. Vanadis had sailed from Glen Cove, where the Billings had a home. Both ships were going slowly due to the fog. At about 19:15 hrs Vanadis sighted Bunker Hill ahead, and immediately reversed her engines, but too late to overcome her momentum and prevent a collision.[25][26]

The yacht hit the passenger steamer's port side. Her bowsprit went through the ceiling of Bunker Hill's dining saloon, where about 70 passengers were dining. It pierced the deck above, wrecking about 20 passenger cabins. Most of the passengers who had booked cabins had not yet retired to them, and thus escaped injury. One passenger was in his cabin, and was severely injured. He was rescued from his cabin, but died at about 20:15 hrs. One member of Bunker Hill's crew was injured and fell overboard. Four other passengers were injured. One of these had chest injuries and a broken leg, and was hospitalized. Passengers reported that Vanadis fell back, and then thrust into Bunker Hill a second time.[25][26]

The passenger ship lowered two lifeboats. The crew of one of these rescued the injured crewman who had fallen overboard. Both of his legs were broken; he had a head injury; and he had been in the water for about ten minutes. He was taken aboard Vanadis, and put in Mr Billings' cabin, but died about an hour later. The yacht lost her bowsprit and much of her rigging; her bow was crumpled; and her foredeck was littered with débris from the passenger ship. However, neither ship was damaged below the waterline, and both remained afloat. Bunker Hill returned to New York, and Vanadis returned to Glen Cove.[25][26]

Minelayer

[edit]The US Navy inspected Bunker Hill on 2 November 1917, and acquired her on 12 November[4] for $1,350,000.[27] In the First World War the US Navy had a policy of naming auxiliary ships after Native American peoples. On 15 November Bunker Hill was renamed Aroostook, after a band of the Mi'kmaq Nation, and given the Naval Registry Identification Number ID-1256. On 7 December she was commissioned at Boston Navy Yard, commanded by Commander James H Tomb.[4]

Aroostook's wooden passenger superstructure was removed, and she was converted into a minelayer. She was defensively armed with one 5-inch/51-caliber gun, two 3-inch/23-caliber dual-purpose guns, and two .30 caliber Colt machine guns. Her complement was 313 officers and enlisted men. She made a shakedown cruise in Massachusetts Bay from 6 to 10 June 1918, and then loaded mines in Boston.[4]

The Navy had also acquired Massachusetts, converted her into a minelayer, and commissioned her as USS Shawmut. In naval sea trials off Provincetown, Massachusetts, Aroostook and Shawmut had shown higher fuel consumption than the Navy expected. The Navy therefore arranged for them to be refueled at sea. On 11 June Aroostook joined Shawmut, the minelayer USS Saranac, and the tender Black Hawk off Cape Cod, and the next day the four ships sailed for Europe. Black Hawk bunkered both Aroostook and Shawmut with fuel oil en route.[4]

On 28 June 1918 Aroostook reached Cromarty Firth in Scotland. She was attached to Mine Squadron 1, which took part in laying the North Sea Mine Barrage. Aroostook laid a total of 3,180 mines:

- planted 320 mines during the 3rd minelaying excursion on 14 July,

- planted 320 mines during the 4th minelaying excursion on 29 July,

- planted 290 mines during the 5th minelaying excursion on 8 August,

- planted 330 mines during the 6th minelaying excursion on 18 August,

- planted 310 mines during the 7th minelaying excursion on 26 August,

- planted 290 mines on 30 August to complete the 7th minefield after Saranac was unable to lay her mines,

- planted 320 mines during the 9th minelaying excursion on 20 September,

- planted 330 mines during the 10th minelaying excursion on 27 September,

- planted 330 mines during the 11th minelaying excursion on 4 October, and

- planted 340 mines during the final 13th minelaying excursion on 24 October.[28]

The barrage was never completed, as the Armistice of 11 November 1918 ended the war. On 14 December 1918 Aroostook and Shawmut left Portland in England, and two days after Christmas they reached Hampton Roads. The next day, Aroostook unloaded her remaining mines onto barges in the York River. She remained in the Hampton Roads area, transferring mines, and taking mines from the minelayer USS Baltimore to the Mine Depot at Yorktown, Virginia.[4]

Aircraft tender

[edit]First transatlantic flight

[edit]

In the spring of 1919, the Navy sought to make the first Transatlantic flight. The Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company built four flying boats for the purpose, the Curtiss NC, which were the largest biplanes yet built. Their route was to be from New York to Lisbon, with refueling and rest stops at Newfoundland and the Azores.

At the beginning of April 1919, Norfolk Navy Yard converted Aroostook into a flying boat tender, to be part of the support detachment in Newfoundland. Tanks for 5,000 US gallons (19,000 L) of gasoline, and cradles for two Curtiss MF flying boats were installed aboard her, and her crew accommodation was modified.[4] She called at New York to load stores, and reached Trepassey Bay, Newfoundland on 2 May.[29] On 5 and 6 May she tried to help to refloat the tanker USS Hisko, which had run aground.[4]

NC-2 had technical problems, and never began the transatlantic attempt. On 10 May NC-1 and NC-3 reached Trepassey Bay, followed by NC-4 on 15 May. On 16 May the three flying boats took off for the Azores. Aroostook left the next day, and on 23 May reached Plymouth, England. NC-1 and NC-3 had to put down on the sea just short of the Azores. Their crews reached land, but neither aircraft completed the journey. NC-4 successfully reached the Azores, and after a ten-day stopover, it reached Lisbon on 27 May. It then flew via Ferrol, Spain to Plymouth, where it touched down on 31 May. Aroostook's crew disassembled and embarked NC-4, and on 18 June she left Plymouth. She crossed the Atlantic via Brest and the Azores, where she called on 23 June for bunkers, food and water. She reached New York on 2 July.[4][30]

Pacific Fleet

[edit]After a fortnight of repairs in Brooklyn, and a week at Newport, Rhode Island awaiting orders, Aroostook embarked supplies and mines at Portsmouth, Virginia. On 12 August she left Portsmouth, and on 18 August she reached Colón, Panama. The next day she passed through the Panama Canal, and on 26 August she bunkered off Salina Cruz, Mexico. She was in port at San Diego from 1 to 10 September. The next day she reached Mare Island Navy Yard, where she unloaded her mines. Thereafter she was based at San Diego.[4] From 22 October 1919, Commander Henry C. Mustin was her commanding officer.[31]

Aroostook was temporarily made flagship of the Air Detachment of the United States Pacific Fleet. She had the hull symbol CM-3.[4] By 1921 her armament had been reduced to one 3-inch/23-caliber gun and two Colt machine guns.[31] In the 1920s she remained mostly in the eastern Pacific Ocean. In the fall of 1920 she was in Balboa, Panama; in the spring of 1921 she was at Guadalupe Island, Mexico; and from April 1925 she was based in Hawaii.[4]

Attempted flight from California to Hawaii

[edit]In August 1925, the Navy tried to fly two PN-9 flying boats non-stop from San Francisco to Hawaii. On 29 August Aroostook, commanded by Commander Wilbur R van Auken, left Hawaii to take up a position 1,800 nautical miles (3,300 km) from California and 300 nautical miles (560 km) from California, as one of the support ships along the intended flight route.[32] On 30 August two PN's took off from San Francisco. An oil leak forced PN-9 No. 3 to touch down after less than five hours, and was rescued by the destroyer USS William Jones. PN-9 No. 1 was consuming fuel at a rate 6 US gallons (23 L) per hour quicker than anticipated. After less than 1,200 miles (1,900 km), her pilot, Commander John Rodgers, realised he would have to touch down. Aided by wireless compass bearings from Aroostook and the minesweeper USS Tanager,[32] he tried to pilot the plane to Aroostook. However, the bearings were incorrect. At 16:15 hrs on 1 September, after more than 25 hours' flying, PN-9 No. 1 ran out of fuel, and touched down in the open ocean. Being without power, the plane was now unable to send or receive wireless signals.[4]

Aroostook, Tanager, and the destroyer Farragut began to search for the flying boat.[32] They were joined by the destroyer Reno, and aircraft from the carrier USS Langley. On 7 September Aroostook put in to Hawaii for bunkers, and then resumed the search.[4]

Admiral Eberle, Chief of Naval Operations, stated that if the flying boat touched down intact, the ocean current would take it toward the Hawaiian Islands. If the flying boat drifted at only 1 knot (2 km/h), it could reach the islands in less than eight days.[33] Eberle proved correct: the flying boat touched down safely; sea conditions remained moderate; and the flying boat floated west. Commander Rodgers and his crew used some of the canvas with which its wings were covered to make makeshift sails, which helped her to sail her toward Hawaii. They sailed west 450 miles (720 km), and on at 16:00 hrs on 10 September the submarine R-4 found the flying boat, only 10 miles (16 km) off the island of Kauai.[4]

Later naval years

[edit]

Aroostook returned to San Diego. In 1926, 1927, and 1929 she visited the Panama Canal Zone for fleet maneuvers. In March 1930 she accompanied the fleet to Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, and then went via Hampton Roads to Washington, D.C. There she embarked a Congressional party, which she returned to Washington on 32 May. That June she returned to San Diego. Later that year she tended planes that bombed the target ships Sloat and Marcus. On 10 March 1931 Aroostook was decommissioned at Puget Sound Navy Yard, and laid up in the reserve fleet.[4]

In 1941 the Navy tried to convert Aroostook back into a cargo ship. That May, she was given the hull number AK-44. She was partly stripped down, but her condition was found to be too poor, so work was stopped. On 5 February 1943 she was struck from the Naval Register; transferred to the War Shipping Administration; and laid up in the Suisun Bay Reserve Fleet. She was listed under her original name Bunker Hill,[4] despite the fact that in 1942 a T2 tanker called Bunker Hill had been completed,[34] and the carrier USS Bunker Hill had been launched.

Gambling ship

[edit]By April 1946, Anthony Cornero's Seven Seas Trading and Steamship Co had bought Bunker Hill; renamed her Lux; and registered her in Los Angeles.[35] Cornero had her converted into a "non-propelled barge",[36] and announced that she would be a floating casino off of Malibu.[37] However, by that July, United States Attorney General Tom C. Clark was backing a bill moved by Senator William Knowland from California to outlaw gambling ships.[38]

Lux was fitted out with tables for roulette, craps, chuck-a-luck, blackjack, and poker. A 300-foot (91 m) line of slot machines was installed in her main saloon, along with a bar 90 feet (27 m) long.[39] She was moored outside the 3-nautical-mile (5.6 km) limit of US territorial waters.[40] Neon lighting illuminated her, and she opened at 17:00 hrs on 6 August. Water taxis with capacity for 60 passengers ferried gamblers between Long Beach and the ship. Plain clothes officers of the Los Angeles County District Attorney's Department and the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department mixed with the gamblers aboard to gather evidence.[39]

In her first three days' trading, Lux made $173,000 profit.[41] On 8 August the Sheriff's Department arrested Cornero and four of his associates. That evening they was released on $2,000 bail each, but Long Beach Police Department officers impounded most of the taxis that were serving the ship, and arrested the crews. Two investigators traveled on each taxi, waited until the passengers had transferred to Lux, and then arrested the taxi crew.[42] By the early hours of 9 August, only one taxi was left operating. Police offered the taxi crews immunity in return for bringing the gamblers back ashore. Either Cornero or the crews (sources differ) rejected the offer, leaving 800 gamblers stranded aboard Lux.[43] One person aboard Lux was taken ill with acute appendicitis. The United States Coast Guard Cutter Yankton was sent to Lux to bring the patient ashore.[44]

One of those arrested with Cornero was George Garvin, who ran the water taxis. Under a truce, the authorities released five of his boats, in order for them to bring the gamblers ashore. Garvin sought an injunction against the authorities who impounded his boats, but on 10 August, Superior Judge Leslie Still in Long Beach refused to grant it. Cornero and Garvin applied to the United States District Court for the Southern District of California in Los Angeles to have the authorities' actions ruled a violation of United States admiralty law. Judge Wiliam C Mathes deferred the case until 12 August.[45] Also on 12 August, Long Beach Police released Garvin's 11 water taxis, but warned that they would impound them again if they tried to take gamblers to Lux again. The District Court hearing was deferred again, this time at Garvin's request, as the Los Angeles Superior Court was due to hear a similar petition on 16 August.[46]

On 31 August, Lux reopened. It was claimed that she had reopened only for dining and dancing. However, Cornero had re-hired his croupiers and card dealers.[47] On 16 September, Municipal Judge Eugene P. Fay in Los Angeles refused to try Cornero for gambling, as gambling outside territorial waters was legal. However, he ruled that Cornero and his three associates could be tried for taking people to a place where they might gamble.[48] The US Coast Guard seized Lux the same day.[49] Customs officers boarded her after she came within the three-mile limit.[50] $36,000 in dollar coins was seized aboard the ship.[51]

United States Attorney James M Carter said Lux would be turned over to the Collector of Customs for the Port of Los Angeles, and a libel would be filed against the ship for engaging in business other than the coastal trade for which she was licensed.[50] In the US District Court for the Southern District of California, Judge JFT O'Connor ordered on 23 November that Lux be forfeited to the Government for that violation.[41] In a separate hearing, Judge Mathes ruled that all her gambling equipment be destroyed.[51] In May 1947, the United States Senate passed Senator Knowland's bill to ban gambling ships. It stipulated a penalty of up to two years imprisonment, of a $10,000 fine and forfeiture of the ship.[52]

The Coast Guard transferred Lux to the United States Maritime Commission. On 24 July 1947 she returned to Suisun Bay, and on 8 August the Maritime Commission advertised her for sale. The Basalt Rock Co, Inc, bought her on 30 September, and on 17 October had her towed away to be broken up.[4] In April and August 1946, Bob Hope twice used the unfolding story of the gambling ship as material for a humorous newspaper column called "It Says Here", which was syndicated to newspapers across the US.[53][54]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "New Haven Steamers". Daily Morning Journal and Courier. Vol. LXXI, no. 99. New Haven. 13 April 1907. p. 9. Retrieved 29 March 2021 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "The Bunker Hill Launched". The New York Times. 27 March 1907. p. 8. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Steamship Bunker Hill Launched". New-York Tribune. Vol. 66, no. 22, 046. 27 March 1907. p. 11. Retrieved 29 March 2021 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Cressman, Robert J (22 January 2018). "Aroostook II (Id. No. 1256)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ a b Bureau of Navigation 1908, p. 167

- ^ a b c d Lloyd's Register 1908, BUL–BUR

- ^ a b "The New Steamer Bunker Hill Here". The New York Times. 19 July 1907. p. 6. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b "Editorial note and comment". Springfield Weekly Republican. Springfield, MA. 26 December 1907. p. 1. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b Colton, Tim (3 September 2014). "Cramp Shipbuilding, Philadelphia PA". Shipbuilding History. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ "New Queen of the Sound". Daily Morning Journal and Courier. Vol. LXXI, no. 184. New Haven, CT. 13 July 1907. p. 3. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "New Sound Flyer". The Willimantic Journal. Vol. LX, no. 48. Willimantic, CT. 29 November 1907. p. 5. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1908, OKI–OLD.

- ^ "Will start new line". The New Haven Union. Vol. LXV, no. 120. 18 November 1907. p. 10. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Competition wiped out". The New Haven Union. Vol. LXV, no. 108. 4 November 1907. p. 5. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "New freight route". The Waterbury Evening Democrat. Vol. XXI, no. 26. Waterbury, CT. 4 January 1908. p. 5. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Open new line to Boston". The New York Times. 5 January 1908. p. 5. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ The Supervising Inspector-General 1908, p. 279.

- ^ "Outside Service Between Boston And New York". The Bridgeport Evening Farmer. Vol. 47, no. 155. Bridgeport, CT. 1 July 1911. p. 3. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b Lloyd's Register 1912, BUL–BUO

- ^ Farr, Bostwick & Willis 1991, p. 39.

- ^ "Steamers crash in Sound". The New York Times. 8 July 1912. p. 2. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Collide on the Sound". The New Haven Union. Vol. LXXV, no. 7. 8 July 1912. p. 2. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ The Marconi Press Agency Ltd 1913, p. 279.

- ^ a b c "Billings yacht hits sound boat in fog; 2 dead". New York Tribune. 14 June 1915. pp. 1, 11. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b c "Billings yacht rams a sound liner; 2 dead". The Sun. New York. 14 June 1915. pp. 1, 14. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ Schmidt 1921, p. 762.

- ^ Belknap 1920, p. 110.

- ^ "Navy flight ship at Newfoundland". The New York Times. 3 May 1919. p. 6. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Mine layer brings in NC-4". The New York Times. 3 July 1919. p. 3. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ a b Radigan, Joseph M. "Aroostook (AK 44) ex-CM-3 ex-ID-1256". Mine Warfare Vessel Photo Archive. NavSource Naval History. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- ^ a b c "Navy plane missing in a stormy sea, its fuel exhausted". The New York Times. 2 September 1925. p. 1. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "No trace of fliers in Pacific search; new flight barred". The New York Times. 3 September 1925. pp. 1, 4. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1943, BUL–BUR.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1946, Supplement: L.

- ^ Lloyd's Register 1947, LUT–LYM.

- ^ "Cornero Says His Gambling Ships Will Be Lawful". The San Bernardino Daily Sun. Vol. 52. Associated Press. 6 April 1946. p. 1.

- ^ "Clark Backs Bill to Curb Gambling Ships Off U. S." The Evening Star. No. 37, 317. Washington, DC. 6 July 1946. p. B–3. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b "Gambling Ship Filled At Touted Opening Off California Coast". The Evening Star. No. 37, 349. Washington, DC. 7 August 1946. p. B–2. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Gambling Ship Defies California; To Start Business Today at Sea". The Evening Star. No. 37, 348. Washington, DC. 6 August 1946. p. B–2. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b "California Gaming Ship Seized by Government". The Evening Star. No. 37, 457. Washington, DC. 23 November 1946. p. A–2. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Gambling ship fight marked by arrests". The New York Times. 9 August 1946. p. 10. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Times Machine.

- ^ "Gamblers Marooned On Casino". The Waterbury Democrat. Vol. LXIV, no. 187. Waterbury, CT. 9 August 1946. p. 12. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "8oo Stranded on Gambling Ship By Impounding of Water Taxis". The Evening Star. No. 37, 351. Washington, DC. 9 August 1946. pp. A–1, A–4. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Court Action Blocks Owner's Attempts to Reopen Gambling Ship". The Evening Star. No. 37, 353. Washington, DC. 11 August 1946. p. A–14. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Police release 11 water taxis". The Wilmington Morning Star. Vol. 79, no. 260. Wilmington, NC. 13 August 1946. p. 9. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Gambling Ship Will Resume Operation". The Sunday Star-News. Vol. 18, no. 36. Wilmington, NC. 1 September 1946. p. 6. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Court's ruling aids gamblers". The Wilmington Morning Star. Vol. 79, no. 290. Wilmington, NC. 17 September 1946. p. 2. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Coast Guard seizes gambling ship; may face Federal court". The Wilmington Morning Star. Vol. 79, no. 291. Wilmington, NC. 18 September 1946. p. 8. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b "Libel Is Filed Against Gambling Ship After Coast Guard Seizure". The Evening Star. No. 37, 391. Washington, DC. 18 September 1946. p. A–7. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ a b "Luxury gambling ship turned back for a naval duty". The Daily Alaska Empire. Vol. LXVIII, no. 10, 472. Juneau, AK. 9 January 1947. p. 8. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ "Senat Passes Measure To Ban Gambling Ships". The Evening Star. No. 57, 622. Washington, DC. 7 May 1947. p. A–14. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ Hope, Bob (26 April 1946). "It Says Here". The Waterbury Democrat. Vol. LXIV, no. 99. Waterbury, CT. p. 13. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

- ^ Hope, Bob (20 August 1946). "It Says Here". The Waterbury Democrat. Vol. LXIV, no. 197. Waterbury, CT. p. 8. Retrieved 24 September 2024 – via Chronicling America.

Bibliography

[edit] This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.- Belknap, Reginald R (1920). The Yankee mining squadron; or, Laying the North Sea mining barrage. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute.

- Bureau of Navigation (1908). Fortieth Annual List of Merchant Vessels of the United States. Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce and Labor – via Google Books.

- Bureau of Navigation (1913). Forty-fifth Annual List of Merchant Vessels of the United States. Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce and Labor – via Google Books.

- Farr, Gail E; Bostwick, Brett F; Willis, Merville (1991). Shipbuilding at Cramp & Sons (PDF). Philadelphia: Philadelphia Maritime Museum. pp. 38–39. ISBN 0913346187. LCCN 91075352. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2021. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Vol. I.–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1908 – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Vol. I.–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1912 – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. II.–Steamers and Motorships of 300 tons. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1943 – via Southampton City Council.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I.–Steamers and Motorships of 300 tons gross and over. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1946 – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I.–Steamers and Motorships of 300 tons gross and over. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1947 – via Internet Archive.

- The Marconi Press Agency Ltd (1913). The Year Book of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony. London: The St Katherine Press.

- Schmidt, Carl H, ed. (1921). "Table 21.—Ships on Navy List June 30, 1919.". Navy Yearbook. Senate Documents. Vol. II. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office – via Google Books.

- The Supervising Inspector-General (1908). Annual Report of The Supervising Inspector-General, Steamboat-Inspection Service. Washington, DC: United States Department of Commerce and Labor – via HathiTrust.

- 1907 ships

- Cargo ships of the United States

- Gambling ships

- Maritime incidents in 1907

- Maritime incidents in 1912

- Maritime incidents in 1915

- Passenger ships of the United States

- Seaplane tenders of the United States Navy

- Ships built by William Cramp & Sons

- Steamships of the United States Navy

- Unique minelayers of the United States Navy

- World War I mine warfare vessels of the United States