Iron oxide nanoparticle

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Nanomaterials |

|---|

|

| Carbon nanotubes |

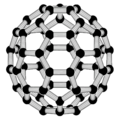

| Fullerenes |

| Other nanoparticles |

| Nanostructured materials |

Iron oxide nanoparticles are iron oxide particles with diameters between about 1 and 100 nanometers. The two main forms are composed of magnetite (Fe3O4) and its oxidized form maghemite (γ-Fe2O3). They have attracted extensive interest due to their superparamagnetic properties and their potential applications in many fields (although cobalt and nickel are also highly magnetic materials, they are toxic and easily oxidized) including molecular imaging.[1]

Applications of iron oxide nanoparticles include terabit magnetic storage devices, catalysis, sensors, superparamagnetic relaxometry, high-sensitivity biomolecular magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic particle imaging, magnetic fluid hyperthermia, separation of biomolecules, and targeted drug and gene delivery for medical diagnosis and therapeutics. These applications require coating of the nanoparticles by agents such as long-chain fatty acids, alkyl-substituted amines, and diols. [citation needed] They have been used in formulations for supplementation.[2]

Structure

[edit]Magnetite has an inverse spinel structure with oxygen forming a face-centered cubic crystal system. In magnetite, all tetrahedral sites are occupied by Fe3+

and octahedral sites are occupied by both Fe3+

and Fe2+

. Maghemite differs from magnetite in that all or most of the iron is in the trivalent state (Fe3+

) and by the presence of cation vacancies in the octahedral sites. Maghemite has a cubic unit cell in which each cell contains 32 oxygen ions, 211⁄3 Fe3+

ions and 22⁄3 vacancies. The cations are distributed randomly over the 8 tetrahedral and 16 octahedral sites.[3][4]

Magnetic properties

[edit]Due to its 4 unpaired electrons in 3d shell, an iron atom has a strong magnetic moment. Ions Fe2+

have also 4 unpaired electrons in 3d shell and Fe3+

have 5 unpaired electrons in 3d shell. Therefore, when crystals are formed from iron atoms or ions Fe2+

and Fe3+

they can be in ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic, or ferrimagnetic states.

In the paramagnetic state, the individual atomic magnetic moments are randomly oriented, and the substance has a zero net magnetic moment if there is no magnetic field. These materials have a relative magnetic permeability greater than one and are attracted to magnetic fields. The magnetic moment drops to zero when the applied field is removed. But in a ferromagnetic material, all the atomic moments are aligned even without an external field. A ferrimagnetic material is similar to a ferromagnet but has two different types of atoms with opposing magnetic moments. The material has a magnetic moment because the opposing moments have different strengths. If they have the same magnitude, the crystal is antiferromagnetic and possesses no net magnetic moment.[5]

When an external magnetic field is applied to a ferromagnetic material, the magnetization (M) increases with the strength of the magnetic field (H) until it approaches saturation. Over some range of fields the magnetization has hysteresis because there is more than one stable magnetic state for each field. Therefore, a remanent magnetization will be present even after removing the external magnetic field.[5]

A single domain magnetic material (e. g. magnetic nanoparticles) that has no hysteresis loop is said to be superparamagnetic. The ordering of magnetic moments in ferromagnetic, antiferromagnetic, and ferrimagnetic materials decreases with increasing temperature. Ferromagnetic and ferrimagnetic materials become disordered and lose their magnetization beyond the Curie temperature and antiferromagnetic materials lose their magnetization beyond the Néel temperature . Magnetite is ferrimagnetic at room temperature and has a Curie temperature of 850 K. Maghemite is ferrimagnetic at room temperature, unstable at high temperatures, and loses its susceptibility with time. (Its Curie temperature is hard to determine). Both magnetite and maghemite nanoparticles are superparamagnetic at room temperature.[5] This superparamagnetic behavior of iron oxide nanoparticles can be attributed to their size. When the size gets small enough (<10 nm), thermal fluctuations can change the direction of magnetization of the entire crystal. A material with many such crystals behaves like a paramagnet, except that the moments of entire crystals are fluctuating instead of individual atoms.[5]

Furthermore, the unique superparamagnetic behavior of iron oxide nanoparticles allows them to be manipulated magnetically from a distance. In the latter sections, external manipulation will be discussed in regards to biomedical applications of iron oxide nanoparticles. Forces are required to manipulate the path of iron oxide particles. A spatially uniform magnetic field can result in a torque on the magnetic particle, but cannot cause particle translation; therefore, the magnetic field must be a gradient to cause translational motion. The force on a point-like magnetic dipole moment m due to a magnetic field B is given by the equation:

In biological applications, iron oxide nanoparticles will be translate through some kind of fluid, possibly bodily fluid,[6] in which case the aforementioned equation can be modified to:[7]

Based on these equations, there will be the greatest force in the direction of the largest positive slope of the energy density scalar field.

Another important consideration is the force acting against the magnetic force. As iron oxide nanoparticles translate toward the magnetic field source, they experience Stokes' drag force in the opposite direction. The drag force is expressed below.

In this equation, η is the fluid viscosity, R is the hydrodynamic radius of the particle, and 𝑣 is the velocity of the particle.[8]

Synthesis

[edit]The preparation method has a large effect on shape, size distribution, and surface chemistry of the particles. It also determines to a great extent the distribution and type of structural defects or impurities in the particles. All these factors affect magnetic behavior. Recently, many attempts have been made to develop processes and techniques that would yield "monodisperse colloids" consisting of nanoparticles uniform in size and shape.

Coprecipitation

[edit]By far the most employed method is coprecipitation. This method can be further divided into two types. In the first, ferrous hydroxide suspensions are partially oxidized with different oxidizing agents. For example, spherical magnetite particles of narrow size distribution with mean diameters between 30 and 100 nm can be obtained from a Fe(II) salt, a base and a mild oxidant (nitrate ions).[9] The other method consists in ageing stoichiometric mixtures of ferrous and ferric hydroxides in aqueous media, yielding spherical magnetite particles homogeneous in size.[10] In the second type, the following chemical reaction occurs:

- 2 Fe3+ + Fe2+ + 8 OH− → Fe3O4↓ + 4 H2O

Optimum conditions for this reaction are pH between 8 and 14, Fe3+

/Fe2+

ratio of 2:1 and a non-oxidizing environment. Being highly susceptibile to oxidation, magnetite (Fe3O4) is transformed to maghemite (γFe2O3) in the presence of oxygen:[3]

- 2 Fe3O4 + O2 → 2 γFe2O3

The size and shape of the nanoparticles can be controlled by adjusting pH, ionic strength, temperature, nature of the salts (perchlorates, chlorides, sulfates, and nitrates), or the Fe(II)/Fe(III) concentration ratio.[3]

Microemulsions

[edit]A microemulsion is a stable isotropic dispersion of 2 immiscible liquids consisting of nanosized domains of one or both liquids in the other stabilized by an interfacial film of surface-active molecules. Microemulsions may be categorized further as oil-in-water (o/w) or water-in-oil (w/o), depending on the dispersed and continuous phases.[4] Water-in-oil is more popular for synthesizing many kinds of nanoparticles. The water and oil are mixed with an amphiphillic surfactant. The surfactant lowers the surface tension between water and oil, making the solution transparent. The water nanodroplets act as nanoreactors for synthesizing nanoparticles. The shape of the water pool is spherical. The size of the nanoparticles will depend on size of the water pool to a great extent. Thus, the size of the spherical nanoparticles can be tailored and tuned by changing the size of the water pool.[11]

High-temperature decomposition of organic precursors

[edit]The decomposition of iron precursors in the presence of hot organic surfactants results in samples with good size control, narrow size distribution (5-12 nm) and good crystallinity; and the nanoparticles are easily dispersed. For biomedical applications like magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic cell separation or magnetorelaxometry, where particle size plays a crucial role, magnetic nanoparticles produced by this method are very useful. Viable iron precursors include Fe(Cup)

3, Fe(CO)

5, or Fe(acac)

3 in organic solvents with surfactant molecules. A combination of Xylenes and Sodium Dodecylbenezensulfonate as a surfactant are used to create nanoreactors for which well dispersed iron(II) and iron (III) salts can react.[3]

Biomedical applications

[edit]Magnetite and maghemite are preferred in biomedicine because they are biocompatible and potentially non-toxic to humans[citation needed]. Iron oxide is easily degradable and therefore useful for in vivo applications[citation needed]. Results from exposure of a human mesothelium cell line and a murine fibroblast cell line to seven industrially important nanoparticles showed a nanoparticle specific cytotoxic mechanism for uncoated iron oxide.[12] Solubility was found to strongly influence the cytotoxic response. Labelling cells (e.g. stem cells, dendritic cells) with iron oxide nanoparticles is an interesting new tool to monitor such labelled cells in real time by magnetic resonance tomography.[13][14] Some forms of Iron oxide nanoparticle have been found to be toxic and cause transcriptional reprogramming.[15][16]

Iron oxide nanoparticles are used in cancer magnetic nanotherapy that is based on the magneto-spin effects in free-radical reactions and semiconductor material ability to generate oxygen radicals, furthermore, control oxidative stress in biological media under inhomogeneous electromagnetic radiation. The magnetic nanotherapy is remotely controlled by external electromagnetic field reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS)-mediated local toxicity in the tumor during chemotherapy with antitumor magnetic complex and lesser side effects in normal tissues. Magnetic complexes with magnetic memory that consist of iron oxide nanoparticles loaded with antitumor drug have additional advantages over conventional antitumor drugs due to their ability to be remotely controlled while targeting with a constant magnetic field and further strengthening of their antitumor activity by moderate inductive hyperthermia (below 40 °C). The combined influence of inhomogeneous constant magnetic and electromagnetic fields during nanotherapy has initiated splitting of electron energy levels in magnetic complex and unpaired electron transfer from iron oxide nanoparticles to anticancer drug and tumor cells. In particular, anthracycline antitumor antibiotic doxorubicin, the native state of which is diamagnetic, acquires the magnetic properties of paramagnetic substances. Electromagnetic radiation at the hyperfine splitting frequency can increase the time that radical pairs are in the triplet state and hence the probability of dissociation and so the concentration of free radicals. The reactivity of magnetic particles depends on their spin state. The experimental data was received about correlation between the frequency of electromagnetic field radiation with magnetic properties and quantity paramagnetic centres of complex. It is possible to control the kinetics of malignant tumor. Cancer cells are then particularly vulnerable to an oxidative assault and induction of high levels of oxidative stress locally in tumor tissue, that has the potential to destroy or arrest the growth of cancer cells and can be thought as therapeutic strategy against cancer. Multifunctional magnetic complexes with magnetic memory can combine cancer magnetic nanotherapy, tumor targeting and medical imaging functionalities in theranostics approach for personalized cancer medicine.[17][18][19][20]

Yet, the use of inhomogeneous stationary magnetic fields to target iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles can result in enhanced tumor growth. Magnetic force transmission through magnetic nanoparticles to the tumor due to the action of the inhomogeneous stationary magnetic field reflects mechanical stimuli converting iron-induced reactive oxygen species generation to the modulation of biochemical signals.[21]

Iron oxide nanoparticles may also be used in magnetic hyperthermia as a cancer treatment method. In this method, the ferrofluid which contains iron oxide is injected to the tumor and then heated up by an alternating high frequency magnetic field. The temperature distribution produced by this heat generation may help to destroy cancerous cells inside the tumor.[22][23][24]

The use of superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO) can also be used as a tracer in sentinel node biopsy instead of radioisotope.[25]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Colombo M, Carregal-Romero S, Casula MF, Gutiérrez L, Morales MP, Böhm IB, Heverhagen JT, Prosperi D, Parak WJ (2012). "Biological applications of magnetic nanoparticles". Chem Soc Rev. 41 (11): 4306–4334. doi:10.1039/c2cs15337h. PMID 22481569.

- ^ Pai AB (2019). "Chapter 6. Iron Oxide Nanoparticle Formulations for Supplementation". In Sigel A, Freisinger E, Sigel RK, Carver PL (eds.). Essential Metals in Medicine: Therapeutic Use and Toxicity of Metal Ions in the Clinic. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. Vol. 19. Berlin: de Gruyter GmbH. pp. 157–180. doi:10.1515/9783110527872-012. ISBN 978-3-11-052691-2. PMID 30855107. S2CID 216683956.

- ^ a b c d Laurent S, Forge D, Port M, Roch A, Robic C, Vander Elst L, Muller RN (June 2008). "Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications". Chemical Reviews. 108 (6): 2064–2110. doi:10.1021/cr068445e. PMID 18543879.

- ^ a b Buschow KH, ed. (2006). Hand Book of Magnetic Materials. Elsevier.

- ^ a b c d Teja AS, Koh PY (2009). "Synthesis, properties, and applications of magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles". Progress in Crystal Growth and Characterization of Materials. 55 (1–2): 22–45. doi:10.1016/j.pcrysgrow.2008.08.003.

- ^ Benz M (2012). "Superparamagnetism:Theory and Applications". Discussion of Two Papers on Magnetic Nanoparticles: 27.

- ^ Magnetic tweezers

- ^ Pankhurst QA, Connolly J, Jones SK, Dobson J (2003). "Applications of magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine". Journal of Physics D: Applied Physics. 36 (13): R167 – R181. doi:10.1088/0022-3727/36/13/201. S2CID 250870659.

- ^ Sugimoto T (1980). "Formation of uniform spherical magnetite particles by crystallization from ferrous hydroxide gels". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 74 (1): 227–243. Bibcode:1980JCIS...74..227S. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(80)90187-3.

- ^ Massart R, Cabuil V (1987). "Monodisperse magnetic nanoparticles: preparation and dispersion in water and oils". J. Chem. Phys. 84: 967–973.

- ^ Laughlin R (1976). "An expedient technique for determining solubility phase boundaries in surfactant–water systems". Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 55 (1): 239–241. Bibcode:1976JCIS...55..239L. doi:10.1016/0021-9797(76)90030-8.

- ^ Brunner TJ, Wick P, Manser P, Spohn P, Grass RN, Limbach LK, et al. (July 2006). "In vitro cytotoxicity of oxide nanoparticles: comparison to asbestos, silica, and the effect of particle solubility". Environmental Science & Technology. 40 (14): 4374–4381. Bibcode:2006EnST...40.4374B. doi:10.1021/es052069i. PMID 16903273.

- ^ Bulte JW, Kraitchman DL (November 2004). "Iron oxide MR contrast agents for molecular and cellular imaging". NMR in Biomedicine. 17 (7): 484–499. doi:10.1002/nbm.924. PMID 15526347. S2CID 19434047.

- ^ Geraldes CF, Delville MH (2021). "Chapter 9. Iron Oxide Nanoparticles for Bio-Imaging". Metal Ions in Bio-Imaging Techniques. Springer. pp. 271–297. doi:10.1515/9783110685701-015. S2CID 233704325.

- ^ Kodali V, Littke MH, Tilton SC, Teeguarden JG, Shi L, Frevert CW, et al. (August 2013). "Dysregulation of macrophage activation profiles by engineered nanoparticles". ACS Nano. 7 (8): 6997–7010. doi:10.1021/nn402145t. PMC 3756554. PMID 23808590.

- ^ Sharma G, Kodali V, Gaffrey M, Wang W, Minard KR, Karin NJ, et al. (September 2014). "Iron oxide nanoparticle agglomeration influences dose rates and modulates oxidative stress-mediated dose-response profiles in vitro". Nanotoxicology. 8 (6): 663–675. doi:10.3109/17435390.2013.822115. PMC 5587777. PMID 23837572.

- ^ Orel VE, Tselepi M, Mitrelias T, Rykhalskyi A, Romanov A, Orel VB, et al. (June 2018). "Nanomagnetic Modulation of Tumor Redox State". Nanomedicine. 14 (4): 1249–1256. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2018.03.002. PMID 29597047. S2CID 4931512.

- ^ Orel VE, Tselepi M, Mitrelias T, Shevchenko AD, Rykhalskiy OY, Golovko TS, et al. (2018). "Magnetic resonance cancer nanotheranostics.". World Congress on Medical Physics and Biomedical Engineering. Singapore: Springer. pp. 651–654.

- ^ Orel V, Shevchenko A, Romanov A, Tselepi M, Mitrelias T, Barnes CH, et al. (January 2015). "Magnetic properties and antitumor effect of nanocomplexes of iron oxide and doxorubicin". Nanomedicine. 11 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1016/j.nano.2014.07.007. PMID 25101880.

- ^ Orel V, Mitrelias T, Tselepi M, Golovko T, Dynnyk O, Nikolov N, et al. (2014). "Imaging of Guerin Carcinoma During Magnetic Nanotherapy". Journal of Nanopharmaceutics and Drug Delivery. 2: 58–68. doi:10.1166/jnd.2014.1044.

- ^ Orel VE, Dasyukevich O, Rykhalskyi O, Orel VB, Burlaka A, Virko S (November 2021). "Magneto-mechanical effects of magnetite nanoparticles on Walker-256 carcinosarcoma heterogeneity, redox state and growth modulated by an inhomogeneous stationary magnetic field". Journal of Magnetism and Magnetic Materials. 538: 168314. Bibcode:2021JMMM..53868314O. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2021.168314.

- ^ Javidi M, Heydari M, Attar MM, Haghpanahi M, Karimi A, Navidbakhsh M, Amanpour S (February 2015). "Cylindrical agar gel with fluid flow subjected to an alternating magnetic field during hyperthermia". International Journal of Hyperthermia. 31 (1): 33–39. doi:10.3109/02656736.2014.988661. PMID 25523967. S2CID 881157.

- ^ Javidi M, Heydari M, Karimi A, Haghpanahi M, Navidbakhsh M, Razmkon A (December 2014). "Evaluation of the effects of injection velocity and different gel concentrations on nanoparticles in hyperthermia therapy". Journal of Biomedical Physics & Engineering. 4 (4): 151–162. PMC 4289522. PMID 25599061.

- ^ Heydari M, Javidi M, Attar MM, Karimi A, Navidbakhsh M, Haghpanahi M, Amanpour S (2015). "Magnetic Fluid Hyperthermia in a Cylindrical Gel Contains Water Flow". Journal of Mechanics in Medicine and Biology. 15 (5): 1550088. doi:10.1142/S0219519415500888.

- ^ Karakatsanis A, Daskalakis K, Stålberg P, Olofsson H, Andersson Y, Eriksson S, et al. (November 2017). "Superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles as the sole method for sentinel node biopsy detection in patients with breast cancer". The British Journal of Surgery. 104 (12): 1675–1685. doi:10.1002/bjs.10606. PMID 28877348. S2CID 28479096.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Magnetite nanoparticles at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Magnetite nanoparticles at Wikimedia Commons