Forster's tern

| Forster's tern | |

|---|---|

| Breeding plumage, at Horicon Marsh in Wisconsin | |

| |

| Nonbreeding plumage, at Bolsa Chica in California | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Laridae |

| Genus: | Sterna |

| Species: | S. forsteri

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sterna forsteri Nuttall, 1834

| |

| |

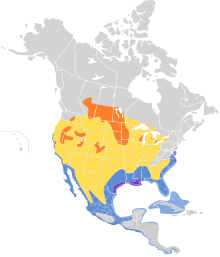

Breeding Migration Year-round Non-breeding

| |

Forster's tern (Sterna forsteri) is a tern in the family Laridae. The genus name Sterna is derived from Old English "stearn", "tern",[2] and forsteri commemorates the naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster.[3]

It breeds inland in North America in the northern United States and southern Canada, and migrates south to winter in the southern United States, Mexico, the Caribbean, and northern Central America. It is also a rare but annual vagrant in western Europe, and has wintered in Ireland and Great Britain on a number of occasions.

This species breeds in colonies in marshes. It nests in a ground scrape and lays two or more eggs. Like all white terns, it is fiercely defensive of its nest and young.

The Forster's tern feeds by plunge-diving for fish, but will also hawk for insects in its breeding marshes. It usually feeds from saline environments in winter, like most Sterna terns. It usually dives directly, and not from the "stepped-hover" favored by the Arctic tern. The offering of fish by the male to the female is part of the courtship display.

This is a medium-small tern, 33–36 cm (13–14 in) long with a 64–70 cm (25–28 in) wingspan and a weight ranging from 130 to 190 g (4.6-6.7 oz ).[4] It is most similar to the common tern, with pale gray upperparts and white underparts. Its legs are red and its bill is red, tipped with black. In winter, the forehead becomes white and a characteristic black eye mask remains. Juvenile Forster's terns are similar to the winter adult. The call is similar to that of common terns, but also some harsher sounds suggestive of a small gull like Bonaparte's gull.

This species is unlikely to be confused with the common tern in winter because of the black eye mask, but is much more similar in breeding plumage. Forster's has a gray center to its white tail, and the upperwings are whiter, without the darker primary wedge of the common tern.

Description

[edit]

Forster's tern is a medium-sized tern with a slender body, deeply forked long tail and relatively long legs.[5][6]

In its non-breeding plumage, the crown is white and a black comma-shaped patch covers the eye and the ear-covert.[5][6][7] The wings are gray with the primaries being dark silvery gray, while the underside is white.[5][6] The bill is black and the legs are a dull brownish red.[5]

When breeding, an intense black cap extending down the neck appears. The wings and the back are pale gray while the underside is bright white. It has a black-tipped orange bill and bright orange legs.[5][7]

The juveniles have coloring similar to a non-breeding adult but often have darker primaries.[5]

Taxonomy

[edit]Forster's tern is a member of the gull and tern family Laridae; it has also been treated like other terns in their own family Sternidae by some authors. Forster's tern was named by Thomas Nuttall in honor of Johann Reinhold Forster, the German naturalist who first suggested it differed from the common tern.[5] Its closest relative is the snowy-crowned tern (S. trudeaui) of South America; the two are sister species and basal to the rest of the genus Sterna.[8]

Habitat and distribution

[edit]Forster's tern is a marsh dwelling species. It can be found either in freshwater, brackish or saltwater. It is often found over shallow open water deep in the marsh.[7] Main habitats are marshes, estuaries, islands, salt marshes and marshy areas surrounding lakes and streams.[5]

Forster's tern is usually restricted to North America.[6] It nests in marshes during the summer, on both the Atlantic and Pacific coast, and also in the Prairies and on the Great Lakes in Canada and the US.[5][6][9] Due to the instability of its nesting habitat, Forster's tern exhibits a high annual turnover rate.[9]

Forster's tern also winters in marshes along the southern coast of the US and Mexico but can sometimes reach the northern extremity of Central America. It is also common for the tern to winter in the Caribbean.[6]

It is a near-annual vagrant to Western Europe and has occasionally wintered in Great Britain and Ireland.[5]

Behavior

[edit]Forster's tern is often found in marshes over shallow open water.[7] It is a shallow plunge-diver that often hovers before attacking. When hunting, its head is pointed downward whereas when travelling, it is pointed forward.[5][10]

It is a colonial nesting species that builds a shallow nest using marsh vegetation and often competes with gulls for nesting sites.[11][12][13] A breeding colony may vary in numbers from a few couples to a thousand individuals.[11] In many occasions, Forster's tern will share nesting sites with the yellow-headed blackbird.[12]

Both parents are involved in brood care and Forster's tern does not exhibit sex-specific differences in space use.[14] Males tend to guard the nest more often during the day while the female is more present at night.[15] When disturbed, newborn chicks tend to crouch and remain silent.[16] Forster's tern is a single prey loader and provision chicks with prey correlated to their size.[17]

Before breeding, males practice courtship feeding.[17]

Vocalization

[edit]The common call of the Forster's tern is a descending kerr.[5][6][7] The threat call used in defensive attack is a low harsh zaar.[5][6] A succession of kerrs is used by the female as a begging call during courtship.[5]

Diet and feeding

[edit]The major constituent of Forster's tern diet is fish. Carp, minnow, sunfish, trout, perch, killifish, stickleback and shiner are common prey in freshwater,[17][18] whereas pompano, herring, menhaden and shiner perch are often consumed in brackish or marine habitats.[11][17] On the West Coast of the United States and Canada, Forster's tern is also known to prey on Pacific lamprey juveniles.[19] Insects such as dragonflies, caddisflies and grasshoppers are often consumed, but aquatic insect larvae, crustaceans and amphibian can complement the diet.[5][11]

The Forster's tern is a shallow plunge-diver, having its head pointing downward when hunting.[5][10] The attack usually starts in a hovering position before initiating a headfirst dive with wings partially folded backward.[10] Insects may occasionally be caught by the wing and prey are swallowed in the air.[10][17] Prey handling behavior may include dropping and re-catching fish before swallowing them.[10] In some areas, Forster's tern tends to prefer forage to turbid water. This may prevent detection but it may also be a sign of higher prey density and increased presence near the surface. Preferences for water clarity may depend on prey availability.[20]

Reproduction

[edit]The breeding season for Forster's tern can start as early as April on the Gulf Coast of the United States and extend from May to mid-June depending on latitude.[5] Forster's tern is a colonial nester with colony size ranging from one to a thousand nests.[11] Adults establish a very small territory around the nest and nests are usually clumped together.[5][11][12] Males will practice courtship feeding and females will beg for food using a kerr kerr kerr call.[5][17]

A typical clutch of eggs ranges from two to four.[21] The incubation period may last 24 or 25 days after laying.[21][22] The young are semi-precocial with shell removal being done by the parents.[11] The chicks have upper- and lower-mandible egg teeth, which they lose three to five days after hatching.[22] The chicks usually leave the nest with the parents four days post hatching and move into areas of denser vegetation.[16][21] Fledging occurs 28 days after hatching.[21] After a few weeks of fledging, young terns leave the natal colony but join the group for roosting, while migrating towards the wintering ground.[5][23]

There is a similar involvement from both male and female in incubation and chick rearing. Males tend to incubate the eggs diurnally and females, mostly nocturnally.[15] Reproductive success varies from year to year and from colony to colony.[12]

Mobbing

[edit]Forster's tern exhibits very aggressive behavior when threatened by nest predators; if a nest is disturbed, the colony mobs the aggressor, diving towards it and issuing loud calls.[24] Aggressiveness increases immediately prior to and during hatching of the chicks. Ducks and grebes nesting in the same area often benefit from the tern's aggressive behavior toward potential predators [11]

Yellow-headed blackbirds sharing nesting sites have been known to actively join tern mobs against predators.[12] Western grebes recognize the tern's alarm call; this can be interpreted as information parasitism.[25]

Nest

[edit]Forster's terns tend to nest in marshy areas, either in freshwater or in estuaries. The nests are usually located deep within the marsh, either on tidal islands or evaporation pond islands, but also on manmade dikes.[11][13] Nests are composed of adjacent marsh vegetation. Many nests are considered floating and are made of marsh grasses, then can be set on top of the vegetation or deposited on floating rafts of vegetation. In Manitoba, there is a strong association between Forster's tern nests and muskrat houses. They are, in fact, highly solicited nesting grounds. Also in Manitoba, Scirpus and often Typha are the main plants used for nest building.[11][12]

In the case of large colonies, nesting area availability decreases. Forster's tern will then nest on sand, gravel or mud.[11] The nests will consist of a hollow in the substrates, either lined with grass or not and driftwood, shells, dried fish, bones and feathers are also often used.[21]

Floating nests are usually tolerant to a slight increase or decrease of water levels but re-nesting is common.[11] Strong wave action, wind or flooding, usually induced by storms, can often damage the nest and eggs. Weather is the main explanation for nest failure and egg loss. Unsheltered nests are more prone to destruction than sheltered ones. Nest made on higher ground are also more shielded from flooding but are more exposed to the wind.[11][12]

Forster's Terns have been recorded using man-made platforms, most notably in Wisconsin, where they were built to substitute for the Cat Island Chain. They demonstrated overall success, with Forster's Terns preferring to use them to avoid the vulnerabilities that come with a natural nest.[26]

Eggs

[edit]The egg's primary color ranges from a greenish to a brownish hue. They are evenly spotted with dark brown, almost black or gray spots. There are color variations between and within clutches; earlier eggs are usually paler, greener and larger. Coloration of the eggs may vary depending on location.[11] Whitish or cream colored eggs have also been reported.[5][11]

Predator

[edit]Raptors such as falcons and hawks, as well as owls and crows may prey on adults and young.[11] There have also been anecdotal reports of snapping turtles preying on young still in the nest.[27] American bittern, great blue heron, and black-crowned night heron are also possible predators while gulls and Caspian terns notably prey on the eggs of the Forster's tern.[11]

When their ranges overlap, marsh rice rats are possibly the most efficient Forster's tern egg predator.[28] American mink are also one of few mammalian predators that can venture in the marsh and prey on eggs and young.[12]

Predator success usually remains low during breeding season due to the aggressive mobbing response of adults.[11]

Status and conservation

[edit]According to the IUCN, the status of the Forster's tern is of little concern,[1] however, degradation of marsh habitat may be threatening. Boating activity may also affect nest vegetation and increase erosion, which may lead to further degradation of tern nesting grounds. Excessive noise may also have caused nest desertion and chick mortality. This species is listed under the Migratory Birds Treaty act in the U.S. It is endangered in Illinois and Wisconsin while being of special concern in Michigan and Minnesota. Preservation of wetlands and introduction of artificial nesting sites may help preserve the species in high-risk areas ([5]).

Increasing populations of carp in drainage systems, causing damage to marsh vegetation, may limit habitat availability for Forster's tern. There have also been anecdotal reports of intense spawning activity of carp damaging tern's floating nests.[12]

As with many species of piscivorous birds, Forster's tern is susceptible to bioaccumulation of pollutants. High mercury concentrations may induce biochemical stress, reducing the overall health of terns.[29] Biomethylation of mercury is increased in marshes and salt ponds, hence increasing the susceptibility of the Forster's tern.[30] High levels of selenium may also have deleterious effects on their health.[31] Organochlorine contaminants such as PCBs may also diminish their breeding success.[32]

Gallery

[edit]-

Breeding

-

Nonbreeding

-

Forster's tern fishing on Lake Mattamuskeet

-

ID composite

References

[edit]- ^ a b BirdLife International (2018). "Sterna forsteri". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2018: e.T22694646A132564836. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22694646A132564836.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ "Sterna". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Forster's Tern Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v "Forster's tern". ARKive. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Forster's tern". The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. Retrieved 12 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d e Sibley, David Allen. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Eastern North America (2nd ed.). New York: Knopf.

- ^ Bridge, Eli S.; Jones, Andrew W.; Baker, Allan J. (2005). "A phylogenetic framework for the terns (Sternini) inferred from mtDNA sequences: implications for taxonomy and plumage evolution". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 35 (2): 459–469. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.12.010. PMID 15804415.

- ^ a b Visser JM and Peterson GW. 1994. Breeding populations and colony site dynamics of seabirds nesting in Louisiana. Colonial Waterbirds. 17(2): 146–152

- ^ a b c d e Salt GW and Willard DE. 1971. The hunting behavior and success of Forster's Tern. Ecology. 52(6): 989–998.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r McNicholl MK. 1971. The breeding biology and ecology of forster's tern (Sterna forsteri) at delta, Manitoba. Thesis. Department of Zoology. University of Manitoba.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i McNicholl MK. 1982. Factors affecting reproductive success of Forster's Terns at Delta Marsh, Manitoba. Colonial Waterbirds. 5(1): 32–38.

- ^ a b Strong CM, Spear LB, Ryan TP and Dakin RE. 2004. Forster's Tern, Caspian Tern, and California Gull colonies in San Francisco Bay: Habitat use, numbers and trends, 1982-2003. Waterbirds. 27(4): 411–423.

- ^ Bluso-Demers, J.; Colwell, M.A.; Takekawa, J.Y.; Ackerman, J.T. (2008). "Space use by Forster's Terns breeding in South San Francisco Bay". Waterbirds. 31 (3): 357–364. JSTOR 25148344.

- ^ a b Bluso-Demers JD, Ackerman JT and Takekawa JY. 2010. Colony attendance patterns by mated Forster's Terns Sterna forsteri using an automated data-logging receiver system. Ardea. 98(1): 59–65.

- ^ a b Hall JA. 1988. Early chick mobility and brood movements in the Forster's Tern (Sterna forsteri). Journal of Field Ornithology. 59(3): 247–251.

- ^ a b c d e f Fraser, G. (1997). "Feeding Ecology of Forster's Terns on Lake Osakis, Minnesota". Colonial Waterbirds. 20 (1): 87–94. doi:10.2307/1521767.

- ^ Taylor, R.A.; Wurtsbaugh, W.A. (1991). "Predation risk and the importance of cover for juvenile rainbow trout in lentic systems". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 120 (6): 728–738. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1991)120<0728:PRATIO>2.3.CO;2.

- ^ <Close DA, Fitzpatrick MS and Li HW. 2002. The ecological and cultural importance of a species at risk of extinction, pacific lamprey. Fisheries. 27(7): 19–25.

- ^ Henkel LA. 2006. Effects of water clarity on the distribution of marine birds in nearshore waters of Monterey Bay, California. Journal of Field Ornithology. 77(2): 151–156

- ^ a b c d e Dakin RE. 2000. Nest site selection by Forster's terns (Sterna forsteri). Master's Theses. San Jose State University. http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2980&context=etd_theses/>

- ^ a b McNicholl, MK. 1983. Hatching of Forster's Terns. The Condor. 85(1): 50–52.

- ^ Ackerman JT, Bluso-Demers JD and Takekawa JY. 2009. Postfledging Forster's tern movements, habitat selection, and colony attendance in San Francisco Bay. The Condor. 111(1): 100–110.

- ^ Siglin RJ and Weller MW. 1963. Comparative nest defense behavior of four species of marsh birds. The Condor. 65(5): 432–437.

- ^ Nuechterlein, GL. (1981). "'Information parasitism' in mixed colonies of western grebes and Forster's terns". Animal Behaviour. 29 (4): 985–989. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(81)80051-6. S2CID 53152999.

- ^ "Green Bay Tern Nesting Platform a Success". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ Pryor GS. 1996. Observations of shorebird predation by snapping turtles in Eastern Lake Ontario. The Wilson Bulletin. 108(1): 190–192.

- ^ Brunjes, J.H.; Webster, W.D. (2003). "Marsh rice rat, Oryzomus palustris, predation on Forster's tern, Sterna forsteri, eggs in coastal North Carolina". Canadian Field-Naturalist. 117 (4): 654–655. doi:10.22621/cfn.v117i4.820.

- ^ Hoffman DJ, Eagles-Smith CA, Ackerman JT, Adelsbach TL, Stebbins KR. 2011. Oxidative stress response of Forster's terns (Sterna forsteri) and Caspian terns (Hydroprogne caspia) to mercury and selenium bioaccumulation in liver, kidney, and brain. Environmental Toxicology. 30(4): 920–929.

- ^ Ackerman JT, Eagles-Smith CA, Takekawa JY, Bluso JD and Adelsbach TL. 2008. Mercury concentrations in blood and feathers of prebreeding forster's terns in relation to space use of san Francisco bay, California, usa, habitats. Environmental Toxicology. 27(4): 897–908.

- ^ Ackerman JT and Eagles-Smith CA. 2009. Selenium bioaccumulation and body condition in shorebirds and terns breeding in San Francisco Bay, California, USA. Environmental Toxicology. 28(10): 2134–2141.

- ^ Kubiak TJ, Harris HJ, Smith LM, Schwarts TR, Stalling DL, Trick JA, Sileo L, Docherty DE and Erdman TC. 1989. Microcontaminants and reproductive impairment of the Forster's tern on Green Bay, Lake Michigan 1983. Archives of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology. 18(5): 706–727.

External links

[edit]- Forster's Tern Species Account - Cornell Lab of Ornithology

- Forster's Tern - Sterna forsteri - USGS Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter

- Field Guide Page on Flickr

- "Forster's Tern media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Forster's Tern photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Sterna forsteri at IUCN Red List maps