Meyer–Schuster rearrangement

| Meyer–Schuster rearrangement | |

|---|---|

| Named after | Kurt Heinrich Meyer Kurt Schuster |

| Reaction type | Rearrangement reaction |

| Identifiers | |

| RSC ontology ID | RXNO:0000476 |

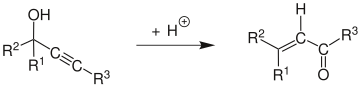

The Meyer–Schuster rearrangement is the chemical reaction described as an acid-catalyzed rearrangement of secondary and tertiary propargyl alcohols to α,β-unsaturated ketones if the alkyne group is internal and α,β-unsaturated aldehydes if the alkyne group is terminal.[1][2][3][4]

Mechanism

[edit]

The reaction proceeds by three major steps: (1) the rapid protonation of oxygen, (2) the slow, rate-determining step comprising the 1,3-shift of the protonated hydroxy group, and (3) the keto-enol tautomerism followed by rapid deprotonation.[5] Formation of the unsaturated carbonyl compound is irreversible.[6] Solvent is important and solvent caging is proposed to stabilize the transition state.[7]

Rupe rearrangement

[edit]The reaction of tertiary alcohols containing an α-acetylenic group does not produce the expected aldehydes, but rather α,β-unsaturated methyl ketones via an enyne intermediate.[8][9] This alternate reaction is called the Rupe reaction, and competes with the Meyer–Schuster rearrangement in the case of tertiary alcohols.

Use of catalysts

[edit]The traditional Meyer–Schuster rearrangement is induced by strong acids, which introduces competition with the Rupe reaction if the alcohol is tertiary.[1] Milder conditions are possible with transition metal-based and Lewis acid catalysts (for example, Ru-[10] and Ag-based[11] catalysts). Microwave-radiation with InCl catalyst to give excellent yields with short reaction times and good stereoselectivity.[12]

Use in organic synthesis

[edit]The Meyer–Schuster rearrangement has been used in a variety of applications, from the conversion of ω-alkynyl-ω-carbinol lactams into enamides using catalytic PTSA[13] to the synthesis of α,β-unsaturated thioesters from γ-sulfur substituted propargyl alcohols[14] to the rearrangement of 3-alkynyl-3-hydroxyl-1H-isoindoles in mildly acidic conditions to give the α,β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds.[15] One of the most interesting applications, however, is the synthesis of a part of paclitaxel in a diastereomerically-selective way that leads only to the E-alkene.[16]

The step shown above had a 70% yield (91% when the byproduct was converted to the Meyer-Schuster product in another step). The authors used the Meyer–Schuster rearrangement because they wanted to convert a hindered ketone to an alkene without destroying the rest of their molecule.

History

[edit]The reaction is named after Kurt Meyer and Kurt Schuster.[17] Reviews have been published by Swaminathan and Narayan,

References

[edit]- ^ a b Swaminathan, S.; Narayan, K. V. "The Rupe and Meyer-Schuster Rearrangements" Chem. Rev. 1971, 71, 429–438. (Review)

- ^ Vartanyan, S. A.; Banbanyan, S. O. Russ. Chem. Rev. 1967, 36, 670. (Review)

- ^ Engel, D.A.; Dudley, G.B. Organic and Biomolecular Chemistry 2009, 7, 4149–4158. (Review)

- ^ Li, J.J. In Meyer-Schuster rearrangement; Name Reactions: A Collection of Detailed Reaction Mechanisms; Springer: Berlin, 2006; pp 380–381.(doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01053-8_159)

- ^ Edens, M.; Boerner, D.; Chase, C. R.; Nass, D.; Schiavelli, M. D. J. Org. Chem. 1977, 42, 3403–3408. (doi:10.1021/jo00441a017)

- ^ Andres, J.; Cardenas, R.; Silla, E.; Tapia, O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988, 110, 666–674. (doi:10.1021/ja00211a002)

- ^ Tapia, O.; Lluch, J.M.; Cardena, R.; Andres, J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989, 111, 829–835. (doi:10.1021/ja00185a007)

- ^ Rupe, H.; Kambli, E. Helv. Chim. Acta 1926, 9, 672. (doi:10.1002/hlca.19260090185)

- ^ Li, J.J. In Rupe rearrangement; Name Reactions: A Collection of Detailed Reaction Mechanisms; Springer: Berlin, 2006; pp 513–514.(doi:10.1007/978-3-642-01053-8_224)

- ^ Cadierno, V.; Crochet, P.; Gimeno, J. Synlett 2008, 1105–1124. (doi:10.1055/s-2008-1072593)

- ^ Sugawara, Y.; Yamada, W.; Yoshida, S.; Ikeno, T.; Yamada, T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 12902-12903. (doi:10.1021/ja074350y)

- ^ Cadierno, V.; Francos, J.; Gimeno, J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009, 50, 4773–4776.(doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.06.040)

- ^ Chihab-Eddine, A.; Daich, A.; Jilale, A.; Decroix, B. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 2000, 37, 1543–1548.(doi:10.1002/jhet.5570370622)

- ^ Yoshimatsu, M.; Naito, M.; Kawahigashi, M.; Shimizu, H.; Kataoka, T. J. Org. Chem. 1995, 60, 4798–4802.(doi:10.1021/jo00120a024)

- ^ Omar, E.A.; Tu, C.; Wigal, C.T.; Braun, L.L. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 1992, 29, 947–951.(doi:10.1002/jhet.5570290445)

- ^ Crich, D.; Natarajan, S.; Crich, J.Z. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 7139–7158.(doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(97)00411-0)

- ^ Meyer, Kurt H.; Schuster, Kurt (1922). "Umlagerung tertiärer Äthinyl-carbinole in ungesättigte Ketone". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (A and B Series). 55 (4): 819–823. doi:10.1002/cber.19220550403.)