Monensin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

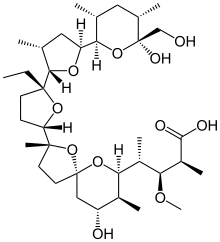

| Preferred IUPAC name

(2S,3R,4S)-4-[(2S,5R,7S,8R,9S)-2-{(2S,2′R,3′S,5R,5′R)-2-Ethyl-5′-[(2S,3S,5R,6R)-6-hydroxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)-3,5-dimethyloxan-2-yl]-3′-methyl[2,2′-bioxolan]-5-yl}-9-hydroxy-2,8-dimethyl-1,6-dioxaspiro[4.5]decan-7-yl]-3-methoxy-2-methylpentanoic acid | |

| Other names

Monensic acid

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.037.398 |

| E number | E714 (antibiotics) |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C36H62O11 | |

| Molar mass | 670.871 g/mol |

| Appearance | solid state, white crystals |

| Melting point | 104 °C (219 °F; 377 K) |

| 3x10−6 g/dm3 (20 °C) | |

| Solubility | ethanol, acetone, diethyl ether, benzene |

| Pharmacology | |

| QA16QA06 (WHO) QP51BB03 (WHO) | |

| Legal status | |

| Related compounds | |

Related

|

antibiotics, ionophores |

Related compounds

|

Monensin A methyl ester, |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Monensin is a polyether antibiotic isolated from Streptomyces cinnamonensis.[2] It is widely used in ruminant animal feeds.[2][3]

The structure of monensin was first described by Agtarap et al. in 1967, and was the first polyether antibiotic to have its structure elucidated in this way. The first total synthesis of monensin was reported in 1979 by Kishi et al.[4]

Mechanism of action

[edit]

Monensin A is an ionophore related to the crown ethers with a preference to form complexes with monovalent cations such as: Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+, Ag+, and Tl+.[5][6] Monensin A is able to transport these cations across lipid membranes of cells in an electroneutral (i.e. non-depolarizing) exchange, playing an important role as an Na+/H+ antiporter. Recent studies have shown that monensin may transport sodium ion through the membrane in both electrogenic and electroneutral manner.[7] This approach explains ionophoric ability and in consequence antibacterial properties of not only parental monensin, but also its derivatives that do not possess carboxylic groups. It blocks intracellular protein transport, and exhibits antibiotic, antimalarial, and other biological activities.[8] The antibacterial properties of monensin and its derivatives are a result of their ability to transport metal cations through cellular and subcellular membranes.[9]

Uses

[edit]Monensin is used extensively in the beef and dairy industries to prevent coccidiosis, increase the production of propionic acid and prevent bloat.[10] Furthermore, monensin, but also its derivatives monensin methyl ester (MME), and particularly monensin decyl ester (MDE) are widely used in ion-selective electrodes.[11][12][13] In laboratory research, monensin is used extensively to block Golgi transport.[14][15][16]

Toxicity

[edit]Monensin has some degree of activity on mammalian cells and thus toxicity is common. This is especially pronounced in horses, where monensin has a median lethal dose 1/100 that of ruminants. Accidental poisoning of equines with monensin is a well-documented occurrence which has resulted in deaths.[17] [18]

References

[edit]- ^ "Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021". Health Canada. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ a b Daniel Łowicki and Adam Huczyński (2013). "Structure and Antimicrobial Properties of Monensin A and Its Derivatives: Summary of the Achievements". BioMed Research International. 2013: 1–14. doi:10.1155/2013/742149. PMC 3586448. PMID 23509771.

- ^ Butaye, P.; Devriese, L. A.; Haesebrouck, F. (2003). "Antimicrobial Growth Promoters Used in Animal Feed: Effects of Less Well Known Antibiotics on Gram-Positive Bacteria". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 16 (2): 175–188. doi:10.1128/CMR.16.2.175-188.2003. PMC 153145. PMID 12692092.

- ^ Nicolaou, K. C.; E. J. Sorensen (1996). Classics in Total Synthesis. Weinheim, Germany: VCH. pp. 185–187. ISBN 3-527-29284-5.

- ^ Huczyński, A.; Ratajczak-Sitarz, M.; Katrusiak, A.; Brzezinski, B. (2007). "Molecular structure of the 1:1 inclusion complex of Monensin A lithium salt with acetonitrile". J. Mol. Struct. 871 (1–3): 92–97. Bibcode:2007JMoSt.871...92H. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2006.07.046.

- ^ Pinkerton, M.; Steinrauf, L. K. (1970). "Molecular structure of monovalent metal cation complexes of monensin". J. Mol. Biol. 49 (3): 533–546. doi:10.1016/0022-2836(70)90279-2. PMID 5453344.

- ^ Huczyński, Adam; Jan Janczak; Daniel Łowicki; Bogumil Brzezinski (2012). "Monensin A acid complexes as a model of electrogenic transport of sodium cation". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes. 1818 (9): 2108–2119. doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.04.017. PMID 22564680.

- ^ Mollenhauer, H. H.; Morre, D. J.; Rowe, L. D. (1990). "Alteration of intracellular traffic by monensin; mechanism, specificity and relationship to toxicity". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Biomembranes. 1031 (2): 225–246. doi:10.1016/0304-4157(90)90008-Z. PMC 7148783. PMID 2160275.

- ^ Huczyński, A.; Stefańska, J.; Przybylski, P.; Brzezinski, B.; Bartl, F. (2008). "Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of Monensin A esters". Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 18 (8): 2585–2589. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.03.038. PMID 18375122.

- ^ Matsuoka, T.; Novilla, M.N.; Thomson, T.D.; Donoho, A.L. (1996). "Review of monensin toxicosis in horses". Journal of Equine Veterinary Science. 16: 8–15. doi:10.1016/S0737-0806(96)80059-1.

- ^ Tohda, Koji; Suzuki, Koji; Kosuge, Nobutaka; Nagashima, Hitoshi; Watanabe, Kazuhiko; Inoue, Hidenari; Shirai, Tsuneo (1990). "A sodium ion selective electrode based on a highly lipophilic monensin derivative and its application to the measurement of sodium ion concentrations in serum". Analytical Sciences. 6 (2): 227–232. doi:10.2116/analsci.6.227.

- ^ Kim, N.; Park, K.; Park, I.; Cho, Y.; Bae, Y. (2005). "Application of a taste evaluation system to the monitoring of Kimchi fermentation". Biosensors and Bioelectronics. 20 (11): 2283–2291. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2004.10.007. PMID 15797327.

- ^ Toko, K. (2000). "Taste Sensor". Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical. 64 (1–3): 205–215. Bibcode:2000SeAcB..64..205T. doi:10.1016/S0925-4005(99)00508-0.

- ^ Griffiths, G.; Quinn, P.; Warren, G. (March 1983). "Dissection of the Golgi complex. I. Monensin inhibits the transport of viral membrane proteins from medial to trans Golgi cisternae in baby hamster kidney cells infected with Semliki Forest virus". The Journal of Cell Biology. 96 (3): 835–850. doi:10.1083/jcb.96.3.835. ISSN 0021-9525. PMC 2112386. PMID 6682112.

- ^ Kallen, K. J.; Quinn, P.; Allan, D. (1993-02-24). "Monensin inhibits synthesis of plasma membrane sphingomyelin by blocking transport of ceramide through the Golgi: evidence for two sites of sphingomyelin synthesis in BHK cells". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Lipids and Lipid Metabolism. 1166 (2–3): 305–308. doi:10.1016/0005-2760(93)90111-l. ISSN 0006-3002. PMID 8443249.

- ^ Zhang, G. F.; Driouich, A.; Staehelin, L. A. (December 1996). "Monensin-induced redistribution of enzymes and products from Golgi stacks to swollen vesicles in plant cells". European Journal of Cell Biology. 71 (4): 332–340. ISSN 0171-9335. PMID 8980903.

- ^ Jennifer Kay (2014-12-16). "Tainted feed blamed for 4 horse deaths at Florida stable". Associated Press.

- ^ Lacy Vilhauer (2024-08-27). "Nearly 70 horses die after eating feed containing monensin". High Plains Journal.