Wheel of Fortune (medieval)

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

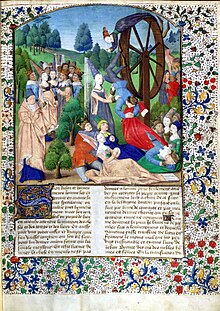

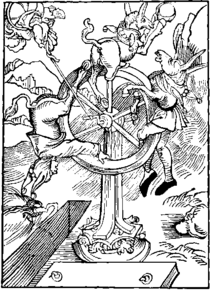

In medieval and ancient philosophy, the Wheel of Fortune or Rota Fortunae is a symbol of the capricious nature of Fate. The wheel belongs to the goddess Fortuna (Greek equivalent: Tyche) who spins it at random, changing the positions of those on the wheel: some suffer great misfortune, others gain windfalls. The metaphor was already a cliché in ancient times, complained about by Tacitus, but was greatly popularized for the Middle Ages by its extended treatment in the Consolation of Philosophy by Boethius from around 520. It became a common image in manuscripts of the book, and then other media, where Fortuna, often blindfolded, turns a large wheel of the sort used in watermills, to which kings and other powerful figures are attached.

Origins

[edit]

The origin of the word is from the "wheel of fortune"—the zodiac, referring to the Celestial spheres of which the 8th holds the stars, and the 9th is where the signs of the zodiac are placed. The concept was first invented in Babylon and later developed by the ancient Greeks, with early references from Cicero's In Pisonem.

Cicero wrote: “The house of your colleague rang with song and cymbals while he himself danced naked at a feast, wherein, even while he executed his whirling gyrations, he felt no fear of the Wheel of Fortune” ("cum conlegae tui domus cantu et cymbalis personaret cumque ipse nudus in convivio saltaret, in quo cum illum saltatorium versaret orbem, ne tum qui dem fortunae rotam pertimescebat")."[1]

The concept somewhat resembles the Bhavacakra, or Wheel of Becoming, depicted throughout Ancient Indian art and literature, except that the earliest conceptions in the Roman and Greek world involve not a two-dimensional wheel but a three-dimensional sphere, a metaphor for the world. It was widely used in the Ptolemaic perception of the universe as the zodiac being a wheel with its "signs" constantly turning throughout the year and having effect on the world's fate (or fortune).

In the second century BC, the Roman tragedian Pacuvius wrote:

Fortunam insanam esse et caecam et brutam perhibent philosophi,

Saxoque instare in globoso praedicant volubili:

Id quo saxum inpulerit fors, eo cadere Fortunam autumant.

Caecam ob eam rem esse iterant, quia nihil cernat, quo sese adplicet;

Insanam autem esse aiunt, quia atrox, incerta instabilisque sit;

Brutam, quia dignum atque indignum nequeat internoscere.Philosophers say that Fortune is insane and blind and stupid,

and they teach that she stands on a rolling, spherical rock:

they affirm that, wherever chance pushes that rock, Fortuna falls in that direction.

They repeat that she is blind for this reason: that she does not see where she's heading;

they say she's insane, because she is cruel, flaky and unstable;

stupid, because she can't distinguish between the worthy and the unworthy.

— Pacuvius, Scaenicae Romanorum Poesis Fragmenta. Vol. 1, ed. O. Ribbeck, 1897

The idea of the rolling ball of fortune became a literary topos and was used frequently in declamation. In fact, the Rota Fortunae became a prime example of a trite topos or meme for Tacitus, who mentions its rhetorical overuse in the Dialogus de oratoribus.

In the second century AD, astronomer and astrologer Vettius Valens wrote:

- There are many wheels, most moving from west to east, but some move from east to west.

- Seven wheels, each hold one heavenly object, the first holds the moon...

- Then the eighth wheel holds all the stars that we see...

- And the ninth wheel, the wheel of fortunes, moves from east to west,

- and includes each of the twelve signs of fortune, the twelve signs of the zodiac.

- Each wheel is inside the other, like an onion's peel sits inside another peel, and there is no empty space between them.[This quote needs a citation]

-

Statuette[2] of the Roman god Fortuna, with gubernaculum (ship's rudder),[3] Rota Fortunae (wheel of fortune) and cornucopia (horn of plenty) found near the altar at Castlecary in 1771.[4]

Boethius

[edit]The goddess and her Wheel were eventually absorbed into Western medieval thought. The Roman philosopher Boethius (c. 480–524) played a key role,[5] utilizing both her and her Wheel in his Consolatio Philosophiae. For example, from the first chapter of the second book:

I know the manifold deceits of that monstrous lady, Fortune; in particular, her fawning friendship with those whom she intends to cheat, until the moment when she unexpectedly abandons them, and leaves them reeling in agony beyond endurance.

[...]

Having entrusted yourself to Fortune's dominion, you must conform to your mistress's ways. What, are you trying to halt the motion of her whirling wheel? Dimmest of fools that you are, you must realize that if the wheel stops turning, it ceases to be the course of chance."[6]

Boethius had a unique perspective on Fortune and blended the concepts from Paganism and Christianity. The Pagans viewed Fortune as an "independent ruling power", whereas Christians viewed Fortune as a "power completely subservient to another God".[7] This allowed Boethius to depict Fortune as having power without denying the fact that a Christian God has control.

In the middle ages

[edit]

Religious instruction

[edit]The Wheel was widely used as an allegory in medieval literature and art to aid religious instruction. Though classically Fortune's Wheel could be favourable and disadvantageous, medieval writers preferred to concentrate on the tragic aspect, dwelling on downfall of the mighty – serving to remind people of the temporality of earthly things. In the morality play Everyman (c. 1495), for instance, Death comes unexpectedly to claim the protagonist. Fortune's Wheel has spun Everyman low, and Good Deeds, which he previously neglected, are needed to secure his passage to heaven.

Geoffrey Chaucer used the concept of the tragic Wheel of Fortune a great deal. It forms the basis for the Monk's Tale, which recounts stories of the great brought low throughout history, including Lucifer, Adam, Samson, Hercules, Nebuchadnezzar, Belshazzar, Nero, Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar and, in the following passage, Peter I of Cyprus.

- O noble Peter, Cyprus' lord and king,

- Which Alexander won by mastery,

- To many a heathen ruin did'st thou bring;

- For this thy lords had so much jealousy,

- That, for no crime save thy high chivalry,

- All in thy bed they slew thee on a morrow.

- And thus does Fortune's wheel turn treacherously

- And out of happiness bring men to sorrow.

~ Geoffrey Chaucer, The Canterbury Tales, The Monk's Tale[8]

Fortune's Wheel often turns up in medieval art, from manuscripts to the great Rose windows in many medieval cathedrals, which are based on the Wheel. Characteristically, it has four shelves, or stages of life, with four human figures, usually labeled on the left regnabo (I shall reign), on the top regno (I reign) and is usually crowned, descending on the right regnavi (I have reigned) and the lowly figure on the bottom is marked sum sine regno (I am without a kingdom). Dante employed the Wheel in the Inferno and a "Wheel of Fortune" trump-card appeared in the Tarot deck (circa 1440, Italy).

Political instruction

[edit]

In the medieval and renaissance period, a popular genre of writing was "Mirrors for Princes", which set out advice for the ruling classes on how to wield power (the most famous being The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli). Such political treatises could use the concept of the Wheel of Fortune as an instructive guide to their readers. John Lydgate's Fall of Princes, written for his patron Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester is a noteworthy example.

Many Arthurian romances of the era also use the concept of the Wheel in this manner, often placing the Nine Worthies on it at various points.

...fortune is so variant, and the wheel so moveable, there nis none constant abiding, and that may be proved by many old chronicles, of noble Hector, and Troilus, and Alisander, the mighty conqueror, and many mo other; when they were most in their royalty, they alighted lowest.

~ Lancelot in Thomas Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, Chapter XVII.[9]

Like the Mirrors for Princes, this could be used to convey advice to readers. For instance, in most romances, Arthur's greatest military achievement – the conquest of the Roman Empire – is placed late on in the overall story. However, in Malory's work the Roman conquest and high point of King Arthur's reign is established very early on. Thus, everything that follows is something of a decline. Arthur, Lancelot and the other Knights of the Round Table are meant to be the paragons of chivalry, yet in Malory's telling of the story they are doomed to failure. In medieval thinking, only God was perfect, and even a great figure like King Arthur had to be brought low. For the noble reader of the tale in the Middle Ages, this moral could serve as a warning, but also as something to aspire to. Malory could be using the concept of Fortune's Wheel to imply that if even the greatest of chivalric knights made mistakes, then a normal fifteenth-century noble didn't have to be a paragon of virtue in order to be a good knight.

Carmina Burana

[edit]The Wheel of Fortune motif appears significantly in the Carmina Burana (or Burana Codex), albeit with a postclassical phonetic spelling of the genitive form Fortunae. Excerpts from two of the collection's better known poems, "Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi (Fortune, Empress of the World)" and "Fortune Plango Vulnera (I Bemoan the Wounds of Fortune)," read:

|

|

|

Later usage

[edit]Fortune and her Wheel have remained an enduring image throughout history. Fortune's wheel can also be found in Thomas More's Utopia.

Shakespeare

[edit]

William Shakespeare in Hamlet wrote of the "slings and arrows of outrageous fortune" and, of fortune personified, to "break all the spokes and fellies from her wheel." And in Henry V, Act 3 Scene VI[10] are the lines:

- Pistol:

- Bardolph, a soldier firm and sound of heart

- And of buxom valor, hath by cruel fate

- And giddy Fortune's furious fickle wheel

- That goddess blind,

- That stands upon the rolling restless stone—

- Fluellen:

- By your patience, Aunchient Pistol. Fortune is painted blind, with a muffler afore his eyes, to signify to you that Fortune is blind; and she is painted also with a wheel, to signify to you, which is the moral of it, that she is turning, and inconstant, and mutability, and variation. And her foot, look you, is fixed upon a spherical stone, which rolls, and rolls, and rolls.

- Pistol:

- Fortune is Bardolph's foe, and frowns on him;

Shakespeare also references this Wheel in King Lear. The Earl of Kent, who was once held dear by the King, has been banished, only to return in disguise. This disguised character is placed in the stocks for an overnight and laments this turn of events at the end of Act II, Scene 2:[11]

- Fortune, good night, smile once more; turn thy wheel!

In Act IV, scene vii, King Lear also contrasts his misery on the "wheel of fire" to Cordelia's "soul in bliss".

Rosalind and Celia also discuss Fortune, especially as it stands opposed to Nature, in As You Like It, Act I, scene ii.

Throughout Shakespeare's works, Fortuna is a powerful force that can make even kings go from greatness to ruin with her wheel. She is often used as a scapegoat to blame when someone experiences a disaster.[12]

Victorian era

[edit]In Anthony Trollope's novel The Way We Live Now, the character Lady Carbury writes a novel entitled The Wheel of Fortune about a heroine who suffers great financial hardships.

References

[edit]- ^ Robinson, David M. (1946). "The Wheel of Fortune". Classical Philology. 41 (4): 207–216. doi:10.1086/362976. ISSN 0009-837X. JSTOR 267004.

- ^ "statuette of Fortuna". Hunterian Museum & Art Gallery Collections: GLAHM F.43. University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on 13 October 2017. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ "Roman statuette of Fortuna". BBC - A History of the World. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

- ^ MacDonald, James (1897). Tituli Hunteriani: An Account of the Roman Stones in the Hunterian Museum, University of Glasgow. Glasgow: T. & R. Annan & Sons. pp. 90–91. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- ^ Patch, Howard Rollin (1927). The Goddess Fortuna in Medieval Literature. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674183780.

- ^ Boethius (2008). The Consolation of Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-0-19-954054-9.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Eric J. (October 1991). "Don Quijote's Windmill and Fortune's Wheel". The Modern Language Review. 86 (4): 885–897. doi:10.2307/3732543. JSTOR 3732543.

- ^ "The Monk's Tale, Modern English – Canterbury Tales – Geoffrey Chaucer (1340?–1400)". Classiclit.about.com. 2009-11-02. Archived from the original on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ^ "Le Morte d' Arthur – Chapter XVII". Worldwideschool.org. Archived from the original on 2016-04-11. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ^ "King Henry V by William Shakespeare: Act 3. Scene VI". Online-literature.com. 2007-01-26. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ^ "Act II. Scene II. King Lear. Craig, W.J., ed. 1914. The Oxford Shakespeare". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 2011-11-24.

- ^ Chapman, Raymond (1950). "The Wheel of Fortune in Shakespeare's Historical Plays". The Review of English Studies. 1 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1093/res/I.1.1. ISSN 0034-6551. JSTOR 511770.

![Statuette[2] of the Roman god Fortuna, with gubernaculum (ship's rudder),[3] Rota Fortunae (wheel of fortune) and cornucopia (horn of plenty) found near the altar at Castlecary in 1771.[4]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/78/Titulihunteriani00macdrich_raw_0143.png/144px-Titulihunteriani00macdrich_raw_0143.png)