Kinkaku-ji

| Rokuon-ji | |

|---|---|

鹿苑寺 | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Buddhism |

| Sect | Zen, Rinzai sect, Shōkoku-ji school |

| Deity | Kannon Bosatsu (Avalokiteśvara) |

| Location | |

| Location | 1 Kinkakuji-chō, Kita-ku, Kyōto, Kyoto Prefecture[1] |

| Country | Japan |

| Geographic coordinates | 35°02′22″N 135°43′43″E / 35.0395°N 135.7285°E |

| Architecture | |

| Founder | Ashikaga Yoshimitsu |

| Completed | 1397 1955 (reconstruction) |

| Website | |

| www.shokoku-ji.jp/en/kinkakuji/ | |

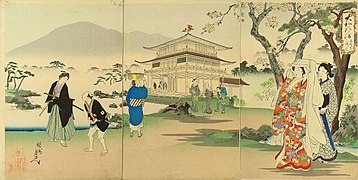

Kinkaku-ji (金閣寺, lit. 'Temple of the Golden Pavilion'), officially named Rokuon-ji (鹿苑寺, lit. 'Deer Garden Temple'), is a Zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto, Japan.[2] It is one of the most popular buildings in Kyoto, attracting many visitors annually.[3] It is designated as a National Special Historic Site, a National Special Landscape and is one of 17 locations making up the Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto which are World Heritage Sites.[4]

History

[edit]

The site of Kinkaku-ji was originally a villa called Kitayama-dai (北山第), belonging to a powerful statesman, Saionji Kintsune.[5] Kinkaku-ji's history dates to 1397, when the villa was purchased from the Saionji family by shōgun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and transformed into the Kinkaku-ji complex.[5] When Yoshimitsu died the building was converted into a Zen temple by his son, according to his wishes.[3][6]

During the Ōnin war (1467–1477), all of the buildings in the complex aside from the pavilion were burned down.[5]

On 2 July 1950, at 2:30 am, the pavilion was burned down[7] by a 22-year-old novice monk, Hayashi Yoken (Kinkaku-ji arson incident), who then attempted suicide on the Daimon-ji hill behind the building. He survived, and was subsequently taken into custody. The monk was sentenced to seven years in prison, but was released because of mental illnesses (persecution complex and schizophrenia) on 29 September 1955; he died of tuberculosis in March 1956.[8] During the fire, the original statue of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu was lost to the flames (now restored). A fictionalized version of these events is at the center of Yukio Mishima's 1956 book The Temple of the Golden Pavilion,[2] and another in the ballet RAkU.

The present pavilion structure dates from 1955, when it was rebuilt.[2] The pavilion is three stories high, 12.5 meters (40 feet) in height.[9] The reconstruction is said to be a close copy of the original, although some have questioned whether such an extensive gold-leaf coating was used on the original structure.[3] In 1984, it was discovered that the gold leaf on the reconstructed building had peeled off, and from 1986 to 1987, it was replaced with 0.5 μm gold leaf, five times the thickness of the gold leaf on the reconstructed building. Although Japanese gold leaf has become thinner with the passage of time due to improved technology, the 0.5 μm gold leaf is as thick as traditional Japanese gold leaf.[10] Additionally, the interior of the building, including the paintings and Yoshimitsu's statue, were also restored. Finally, the roof was restored in 2003. The name Kinkaku (金閣 gold pavilion) is derived from the gold leaf that the pavilion is covered in. Gold was an important addition to the pavilion because of its underlying meaning. The gold employed was intended to mitigate and purify any pollution or negative thoughts and feelings towards death.[11] Other than the symbolic meaning behind the gold leaf, the Muromachi period heavily relied on visual excesses.[12] With the focus on the Golden Pavilion, the way that the structure is mainly covered in that material creates an impression that stands out because of the sunlight reflecting and the effect the reflection creates on the pond.

Design details

[edit]

The Golden Pavilion (金閣, Kinkaku) is a three-story building on the grounds of the Rokuon-ji temple complex.[13] The top two stories of the pavilion are covered with pure gold leaf.[13] The pavilion functions as a shariden (舎利殿), housing relics of the Buddha (Buddha's Ashes). The building was an important model for Ginkaku-ji (Silver Pavilion Temple) and Shōkoku-ji, which are also located in Kyoto.[2] When these buildings were constructed, Ashikaga Yoshimasa employed the styles used at Kinkaku-ji and even borrowed the names of its second and third floors.[2]

Architectural design

[edit]

The pavilion successfully incorporates three distinct styles of architecture, which are shinden, samurai and zen, specifically on each floor.[9] Each floor of the Kinkaku uses a different architectural style.[2]

The first floor, called The Chamber of Dharma Waters (法水院, Hō-sui-in), is rendered in shinden-zukuri style, reminiscent of the residential style of the 11th century Heian imperial aristocracy.[2] It is evocative of the Shinden palace style. It is designed as an open space with adjacent verandas and uses natural, unpainted wood and white plaster.[9] This helps to emphasize the surrounding landscape. The walls and fenestration also affect the views from inside the pavilion. Most of the walls are made of shutters that can vary the amount of light and air into the pavilion[9] and change the view by controlling the shutters' heights. The second floor, called The Tower of Sound Waves (潮音洞, Chō-on-dō ),[2] is built in the style of warrior aristocrats, or buke-zukuri. On this floor, sliding wood doors and latticed windows create a feeling of impermanence. The second floor also contains a Buddha Hall and a shrine dedicated to the goddess of mercy, Kannon.[9] The third floor is built in traditional Chinese chán (Jpn. zen) style, also known as zenshū-butsuden-zukuri. It is called the Cupola of the Ultimate (究竟頂, Kukkyō-chō). The zen typology depicts a more religious ambiance in the pavilion, as was popular during the Muromachi period.[9]

The roof is in a thatched pyramid with shingles.[14] The building is topped with a bronze hōō (phoenix) ornament.[13] From the outside, viewers can see gold plating added to the upper stories of the pavilion. The gold leaf covering the upper stories hints at what is housed inside: the shrines.[11] The outside is a reflection of the inside. The elements of nature, death, religion, are formed together to create this connection between the pavilion and outside intrusions.

Garden design

[edit]The Golden Pavilion is set in a Japanese strolling garden (回遊式庭園, kaiyū-shiki-teien, lit. a landscape garden in the go-round style).[6] The location implements the idea of borrowing of scenery ("shakkei") that integrates the outside and the inside, creating an extension of the views surrounding the pavilion and connecting it with the outside world. The pavilion extends over a pond, called Kyōko-chi (鏡湖池, Mirror Pond), that reflects the building.[5] The pond contains 10 smaller islands.[9] The zen typology is seen through the rock composition; the bridges and plants are arranged in a specific way to represent famous places in Chinese and Japanese literature.[9] Vantage points and focal points were established because of the strategic placement of the pavilion to view the gardens surrounding the pavilion.[12] A small fishing hall (釣殿, tsuri-dono) or roofed deck is attached to the rear of the pavilion building, allowing a small boat to be moored under it.[5] The pavilion grounds were built according to descriptions of the Western Paradise of the Buddha Amida, intending to illustrate a harmony between heaven and earth.[6] The largest islet in the pond represents the Japanese islands.[5] The four stones forming a straight line in the pond near the pavilion are intended to represent sailboats anchored at night, bound for the Isle of Eternal Life in Chinese mythology.[5]

The garden complex is an excellent example of Muromachi period garden design.[13] The Muromachi period is considered to be a classical age of Japanese garden design.[12] The correlation between buildings and its settings were greatly emphasized during this period.[12] It was an artistic way to integrate the structure within the landscape. The garden designs were characterized by a reduction in scale, a more central purpose, and a distinct setting.[15] A minimalistic approach was brought to the garden design by recreating larger landscapes in a smaller scale around a structure.[15]

Gallery

[edit]-

1930s travel poster

-

Entrance and ticket booth

-

Kinkaku-ji close up

-

Interior

-

Kinkaku-ji garden

-

The lower pond

-

White Snake Pagoda of Kinkaku-ji

-

Kinkaku-Ji, Kyoto in May 2019

-

Kinkaku-ji keychain

See also

[edit]- The Temple of the Golden Pavilion by Yukio Mishima, a novel loosely based on the 1950 destruction of Kinkaku-ji

- Buntenkaku in Nagoya, modeled after the Golden Pavilion

- Ginkaku-ji

- Shōkoku-ji

- Chūson-ji with golden Konjiki-dō

- Golden Tea Room

- List of Special Places of Scenic Beauty, Special Historic Sites and Special Natural Monuments

- Historic Monuments of Ancient Kyoto (Kyoto, Uji and Otsu Cities)

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Tourist Facilities of Japan - Kinkaku-ji Temple Garden". Japan National Tourism Organization. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Kinkakuji Temple - 金阁寺, Kyoto, Japan". Oriental Architecture. Retrieved 2010-07-13.

- ^ a b c Bornoff, Nicholas (2000). The National Geographic Traveler: Japan. National Geographic Society. ISBN 0-7922-7563-2.

- ^ "Places of Interest in Kyoto (Top 15 most visited places in Kyoto by visitors from overseas)". Asano Noboru. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Kinkaku-ji in Kyoto". Asano Noboru. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

- ^ a b c Scott, David (1996). Exploring Japan. Fodor's Travel Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-679-03011-5.[page needed]

- ^ Cartwright, Mark. "Kinkakuji". World History Encyclopedia. UNESCO. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Albert Borowitz (2005). Terrorism for self-glorification: the Herostratos syndrome. Kent State University Press. pp. 49–62. ISBN 978-0-87338-818-4. Retrieved 1 July 2011. See: Herostratos syndrome

- ^ a b c d e f g h Young, David, and Michiko Young. The art of Japanese Architecture. North Claredon, VT: Turtle Publishing, 2007. N. pag. Print.[page needed]

- ^ Kazuo Yaguchi. 金閣寺大修復 金閣修復 五倍箔 (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 23 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ a b Gerhart, Karen M. The material culture of Death in medieval Japan. N.p.: University of Hawaii Press, 2009. N. pag. Print.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d “Pregil, Philip, and Nancy Volkman. Landscapes in History: Design and Planning in the Eastern and Western tradition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1992. N. pag. Print.”.

- ^ a b c d Eyewitness Travel Guides: Japan. Dorling Kindersley Publishing (2000). ISBN 0-7894-5545-5.

- ^ Young, David, Michiko Young, and Tan Hong. The material culture of Death in medieval Japan. North Claredon, VT: Turtle Publishing, 2005. N. pag. Print.

- ^ a b Boults, Elizabeth, and Chip Sullivan. Illustrated History of Landscape Design. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons INc., 2010. N. pag. Print.

References

[edit]- Boults, Elizabeth, and Chip Sullivan. Illustrated History of Landscape Design. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

- Gerhart, Karen M. The Material Culture of Death in Medieval Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009.

- Pregil, Philip, and Nancy Volkman. Landscapes in History: Design and Planning in the Eastern and Western Tradition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 1992.

- Young, David, and Michiko Young. The Art of Japanese Architecture. North Claredon, VT: Tuttle Publishing, 2007.

- Young, David, Michiko Young, and Tan Hong. Introduction to Japanese Architecture. North Claredon, VT: Periplus, 2005.

Further reading

[edit]- Kawaguchi, Yoko (2014). Japanese Zen Gardens (Hardback). London: Francis Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-3447-5.

- Schirokauer, Conrad; Lurie, David; Gay, Suzanne (2005). A Brief History of Japanese Civilization. Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-0-618-91522-4. OCLC 144227752.

External links

[edit]- Official site of Kinkaku-ji

- Oriental Architecture – Kinkakuji Temple

- Omamori Charms Amulets of Kinkaku-ji Temple

Geographic data related to Kinkaku-ji at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Kinkaku-ji at OpenStreetMap

- 1397 establishments

- 14th-century Buddhist temples

- 20th-century Buddhist temples

- Buddhist temples in Kyoto

- Important Cultural Properties of Japan

- Myoshin-ji temples

- Rebuilt buildings and structures in Japan

- Religious buildings and structures completed in 1955

- Religious buildings and structures destroyed by arson

- Special Historic Sites

- Special Places of Scenic Beauty

- World Heritage Sites in Japan

- Attacks on religious buildings and structures in Japan