The Crow (1994 film)

| The Crow | |

|---|---|

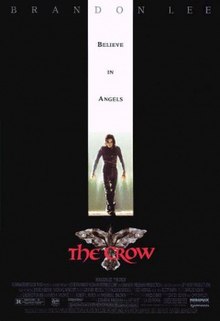

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alex Proyas |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | The Crow by James O'Barr |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Dariusz Wolski |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Graeme Revell |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | |

Release date |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $23 million[1] |

| Box office | $94 million[2] |

The Crow is a 1994 American superhero film[3][4][5] directed by Alex Proyas and written by David J. Schow and John Shirley, based on the 1989 comic book series by James O'Barr. It stars Brandon Lee in his final film role, as Eric Draven, a rock musician who is resurrected from the dead to seek vengeance against the gang who murdered him and his fiancée.

Lee was fatally wounded by a prop gun during filming. As he had finished most of his scenes, the film was completed through script rewrites, a stunt double and digital effects.[6] After Lee's death, Paramount Pictures opted out of distribution and the rights were acquired by Miramax Films. The film is dedicated to Lee and his fiancée, Eliza Hutton.

The Crow premiered in Santa Monica on May 10, 1994, and was released in the United States on May 13, 1994, by Dimension Films. The film received positive reviews for its style and Lee's performance.[7] It grossed $94 million on a $23 million budget and has gained a cult following. The success led to a media franchise that includes the sequels The Crow: City of Angels (1996), The Crow: Salvation (2000), and The Crow: Wicked Prayer (2005). The sequels, which mostly featured different characters and none of the original cast members, were unable to match the success of the first film. A reboot of The Crow was released in 2024, which was a critical and commercial failure.

Plot

[edit]On Devil's Night, in a crime-ravaged and decrepit Detroit, a young woman, Shelly Webster, is raped and seriously wounded while her rock musician fiancé Eric Draven is shot and thrown to his death from the window of their loft apartment. Police Sergeant Daryl Albrecht accompanies Shelly to the hospital, but she eventually dies from her injuries. A narration states the legend of a crow that carries souls to the land of the dead; if the person died in tragic circumstances, the crow can resurrect their restless spirit to set things right.

One year later, Shelly's and Eric's graves are visited by Sarah, a young girl the pair cared for due to her absent mother. A crow lands on Eric's gravestone and taps on it, resurrecting him. Disoriented and distressed, Eric returns to his ravaged loft apartment and experiences flashbacks of the murders: A gang of men—Tin Tin, Funboy, T-Bird, and Skank—targeted the pair, because they were protesting forced evictions in their apartment building which the gang's leader, ruthless crime boss Top Dollar, intended to seize. Realizing that any injuries he suffers are immediately healed, Eric dons black-and-white face paint and sets out to avenge himself and Shelly, guided by the crow.

The crow leads Eric to Tin Tin, whom Eric stabs to death. He next travels to the pawn shop where Tin Tin had pawned Shelly's engagement ring. Eric recovers the ring and blows up the shop, but spares the owner Gideon so he can alert Top Dollar's men that Eric is coming for them. Albrecht begins investigating the apparent vigilante disturbances while Eric finds Funboy taking drugs with Sarah's estranged drug addict mother, Darla. He gives Funboy a fatal overdose and purges the drugs from Darla's body, telling her that Sarah needs her.

Eric visits Albrecht and confirms his suspicions regarding the vigilante's identity. Albrecht tells Eric that he stayed with Shelly until she died, witnessing the thirty hours of suffering she experienced. Eric touches Albrecht, absorbing the pain Shelly felt. Later, Eric saves Sarah from being hit by a car, revealing to her that he has returned. Eric next targets T-Bird, killing him in an explosion. The following morning, Sarah and Darla reconcile and Sarah reunites with Eric at his apartment. Top Dollar holds a meeting with his associates to discuss his plans to burn the city to the ground on Devil's Night. Eric arrives for Skank but a gunfight erupts, ending with Eric throwing Skank from a window to his death. Top Dollar, his lover and half-sister Myca, and his right-hand man Grange escape. Myca correctly hypothesizes that the crow is the source of Eric's immortality.

Satisfied with his vengeance, Eric gifts Shelly's engagement ring to Sarah and returns to his grave. Grange abducts Sarah as she is walking home and takes her to an abandoned church with Myca and Top Dollar, who takes Shelly's ring. Eric is alerted to her plight by the crow and rushes to rescue her, but he is ambushed by Grange who wounds the crow, rendering Eric vulnerable. Albrecht arrives and kills Grange, while Myca attempts to take the crow for its immortality; it claws her eyes out, causing her to fall to her death from the bell tower. Top Dollar retreats to the church roof with Sarah, where he fights and badly wounds Eric. Eric transfers Shelly's pain into Top Dollar, causing him to stumble off the roof and be impaled on a gargoyle, killing him.

Sarah and a wounded Albrecht are recovered from the church, while a pained Eric goes to Shelly's grave where her spirit arrives to comfort him and return his body to rest. Sometime later, Sarah visits the graves and the crow returns Shelly's ring to her.

Cast

[edit]- Brandon Lee as Eric Draven / The Crow

- Rochelle Davis as Sarah

- Ernie Hudson as Sergeant Albrecht

- Michael Wincott as Top Dollar

- Bai Ling as Myca

- Sofia Shinas as Shelly Webster

- Anna Levine as Darla

- David Patrick Kelly as T-Bird

- Angel David as Skank

- Laurence Mason as Tin Tin

- Michael Massee as Funboy

- Tony Todd as Grange

- Jon Polito as Gideon

- Bill Raymond as Mickey

- Marco Rodríguez as Detective Torres

Michael Berryman filmed scenes as the Skull Cowboy, Eric's spirit guide, but his scenes were cut from the finished film. Chad Stahelski was Brandon Lee's stunt double in several scenes.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]James O'Barr wrote what would become The Crow as a means to cope with the unexpected death of his fiancée, who was killed by a drunk driver.[8] The first meeting O'Barr had with a major studio was quickly dismissed after the studio's vision for the film was a musical with Michael Jackson as the lead.[9] Around the time of The Crow's publication, writer John Shirley pitched Angry Angel to Caliber Press, who turned it down due to similarities with The Crow. Shirley sought the comic out and decided to adapt it into a film.[10] O'Barr was receptive and agreed to workshop the film with Shirley and producer Jeff Most, turning down a significant offer from New Line Cinema in the process. O'Barr oversaw three different script treatments by Shirley and Most before directly collaborating on the first two drafts of the screenplay. Shirley penned the third and fourth draft by himself which awarded him screenplay credit by the Writers Guild of America. Most claimed to have written a "substantial proportion" of the script, but was denied credit due to a rule in the WGA which prohibited producers from receiving credit.[11] The addition of producer Edward Pressman gave The Crow further momentum, but Shirley would be fired during development after clashing with a development head at Pressman's studio.[12] Splatterpunk writer David J. Schow was brought in for rewrites.[4] From a suggestion by Most, Pressman primarily pursued music video and commercial directors to helm the film; Julien Temple being Most's top choice.[13] Australian filmmaker Alex Proyas was hired to direct the film.[10] Paramount Pictures picked up the distribution rights and slotted an August 1993 release date.[14]

River Phoenix and Christian Slater were early considerations for the role of Eric Draven.[15][16] Shirley and Most pushed for Slater while Pressman wanted River Phoenix.[17] Brandon Lee was suggested to play Draven, but O'Barr was unconvinced fearing he wouldn't be suited for the material. However, Lee won O'Barr over and was given the role shortly thereafter.[18] Lee dropped 20 pounds to portray Draven and worked closely with the crew to shape the film, co-choreographing his action sequences with Jeff Imada, performing most of his stunts, and removing a subplot due to its Asian stereotyping.[19][20][3] Rochelle Davis, Ernie Hudson, Michael Wincott, Bai Ling, Sofia Shinas, Michael Massee, David Patrick Kelly, Tony Todd, and Jon Polito rounded out the supporting cast.

Filming

[edit]Production began on The Crow in February 1993 in Wilmington, North Carolina and was scheduled to last 54 days.[21][14]

Brandon Lee's death

[edit]On March 31, 1993, at EUE Screen Gems Studios in Wilmington, North Carolina, Lee was filming a scene where his character, Eric, is shot after witnessing the beating and rape of his fiancée. Actor Michael Massee's character Funboy fires a .44 Magnum Smith & Wesson Model 629 revolver at Lee as he walks into the room.[22] A scene filmed two weeks before Lee's had called for the same gun to be shown in close-up. Revolvers often use dummy cartridges fitted with bullets, but no powder or primer, during close-ups as they look more realistic than blank rounds which have no bullet. Instead of purchasing commercial dummy cartridges, the film's prop crew, hampered by time and money constraints, created their own by pulling the bullets from live rounds, dumping the powder charge but not the primer, then reinserting the bullets. Witnesses reported that two weeks before Lee's death they saw an unsupervised actor pulling the trigger on the gun while it was loaded with the powderless but primed round. Having not removed the primer, the primer could detonate with enough energy to launch a bullet and lodge it in the barrel.[23][24]

In the fatal scene, which called for the revolver to be actually fired at Lee from a distance of 12–15 feet, the dummy cartridges were exchanged for blank rounds, which feature a live powder charge and primer, but no bullet, thus allowing the gun to be fired without the risk of an actual projectile. As the production company had sent the firearms specialist home early, responsibility for the guns was given to a prop assistant who was unaware of the rule for inspecting all firearms before and after any handling. Therefore, the barrel was not checked for obstructions when the time came to load it with the blank rounds.[23][24] Since the bullet from the dummy round was already trapped in the barrel (a condition known as a squib load), this caused the .44 Magnum bullet to be fired out of the barrel with virtually the same force as if the gun had been loaded with a live round, and it struck Lee in the abdomen, mortally wounding him.[25][26]

After Lee's death, the producers were faced with the decision of whether or not to continue with the film. Lee had completed most of his scenes for the film and was scheduled to shoot for only three more days.[1] The rest of the cast and crew, except for Ernie Hudson, whose brother-in-law had just died, stayed in Wilmington. Paramount Pictures, which was initially interested in distributing The Crow theatrically (originally a direct-to-video feature), opted out of involvement due to delays in filming and some controversy over the violent content being inappropriate given Lee's death. However, Miramax picked it up with the intention of releasing it in theatres and injected a further $8 million to complete the production, taking its budget to approximately $23 million.[1] The cast and crew then took a break for script rewrites of the flashback scenes that had yet to be completed.[23] The script was rewritten by Walon Green, Terry Hayes, René Balcer, and Michael S. Chernuchin, adding narration and new scenes.[27][28] Lee's stunt double Chad Stahelski was used as a stand-in and digital face replacement was used to superimpose Lee's face onto the head of the double. The beginning of the movie, which had not been finished, was rewritten, and the apartment scene remade using computer graphics from an earlier scene of Lee.[29]

A character from the original comic book called Skull Cowboy was originally planned to be part of the adaptation and even had scenes filmed. He acted as a guide for Eric Draven between the worlds of the dead and the living. He was set to be played by Michael Berryman, but the role was cut from the film due to Lee's death.[30]

O'Barr later remarked that losing Lee was like losing his fiancée all over again, and he regretted ever writing the comic in the first place.[31]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film opened at number one in the United States in 1,573 theaters with $11,774,332 and averaging $7,485 per theater, making it Miramax's biggest ever opening.[32][33] Some industry sources believed that Miramax overstated the weekend gross by as much as $1 million.[34] The film ultimately grossed $50,693,129 in the United States and Canada, and $43 million internationally, for a worldwide total of $93.7 million against its budget of $23 million.[35][2] It ranked at number 24 for all films released in the US in 1994, the 24th highest-grossing film worldwide for 1994 and number 10 for R-rated films released that year.[36][2]

In Europe, the film grossed £1,245,403 in the United Kingdom (where it was 18-rated),[37] and sold 4,604,115 tickets in France, Germany, Italy and Spain.[38][39] In Seoul, South Korea, it sold 83,126 tickets.[40]

Critical response

[edit]The Crow has an approval rating of 87% on Rotten Tomatoes based on 75 reviews and an average rating of 7.2/10. The critical consensus states: "Filled with style and dark, lurid energy, The Crow is an action-packed visual feast that also has a soul in the performance of the late Brandon Lee."[7] The film also has a score of 71 out of 100 on Metacritic based on 14 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[41]

Reviewers praised the action and visual style.[42][43] Rolling Stone called it a "dazzling fever dream of a movie"; Caryn James, writing for The New York Times, called it "a genre film of a high order, stylish and smooth"; and Roger Ebert called it "a stunning work of visual style".[43][44][45] The Los Angeles Times praised the film also.[46][47]

Lee's death was alleged to have a melancholic effect on viewers; Desson Howe of The Washington Post wrote that Lee "haunts every frame" and James Berardinelli called the film "a case of 'art imitating death', and that specter will always hang over The Crow".[42][43][48] Both Berardinelli and Howe called it an appropriate epitaph to Lee, and Ebert stated that not only was this Lee's best film, but it was better than any of his father's.[42][43][48] Critics generally thought that this would have been a breakthrough film for Lee, although Berardinelli disagreed.[43][48][49] The changes made to the film after Lee's death were noted by reviewers, most of whom saw them as an improvement. Howe said that it had been transformed into something compelling.[42] Berardinelli, although terming it a genre film, said that it had become more mainstream because of the changes.[48]

The film was widely compared to other films, particularly Tim Burton's Batman movies and Ridley Scott's Blade Runner.[48][49] Critics described The Crow as a darker film than the others;[48] Ebert called it a grungier and more forbidding story than those of Batman and Blade Runner, and Todd McCarthy of Variety wrote that "it’s set in a generic inner city so hellish it makes Gotham City look like the Emerald City".[49]

While the plot and characterization were found to be lacking,[42][48][49] these faults were considered to be overcome by the action and visual style.[43][48] The cinematography by Dariusz Wolski and the production design by Alex McDowell were also praised. The cityscape designed by McDowell and the production team was described by McCarthy as rendered imaginatively.[49] The film's comic book origins were noted, and Ebert called it the best version of a comic book universe he had seen.[43] McCarthy agreed, calling it "one of the most effective live-actioners ever derived from a comic strip".[49] Critics felt that the soundtrack complemented this visual style, calling it blistering, edgy and boisterous.[42][44][49] Graeme Revell was praised for his "moody" score;[49] Howe said that it "drapes the story in a postmodern pall."[42]

Negative reviews of the film were generally similar in theme to the positive ones but said that the interesting and "OK" special effects did not make up for the "superficial" plot, "badly-written" screenplay and "one-dimensional" characters.[50][51]

The Crow is mentioned in Empire's 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time; it ranked at number 468.[52] It has since become a cult film.[53]

Accolades

[edit]- 7th – Sandi Davis, The Oklahoman[54]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Matt Zoller Seitz, Dallas Observer[55]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Mike Mayo, The Roanoke Times[56]

- Top 10 (not ranked) – Betsy Pickle, Knoxville News-Sentinel[57]

- Top 12 worst (Alphabetically ordered, not ranked) – David Elliott, The San Diego Union-Tribune[58]

- Top 3 "Best in-your-face exploitation" (not ranked) – Glenn Lovell, San Jose Mercury News[59]

| Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| MTV Movie Award[60] | Best Movie of the Year | Nominated | |

| Best Actor | Brandon Lee (posthumous) | Nominated | |

| Best Song | Stone Temple Pilots For the song "Big Empty" |

Won | |

| Saturn Awards | Best Horror Film | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Alex Proyas | ||

| Best Costume Design | Arianne Phillips | ||

| Best Special Effects | Andrew Mason (International Creative Effects) |

Soundtracks

[edit]The original soundtrack album for The Crow features songs from the film, and was a chart-topping album. It included work by The Cure (their song, "Burn", became the film's main theme), The Jesus and Mary Chain, Rage Against the Machine and Helmet, among many others. In Peter Hook's memoir Substance: Inside New Order, Hook relates that New Order were approached to provide the soundtrack for the film, with a cover of "Love Will Tear Us Apart", their hit as Joy Division, citing parallels between Eric's resurrection and New Order's formation after the suicide of Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis. However, New Order frontman Bernard Sumner declined, stating that they were too busy with their album Republic to commit to another project. James O'Barr, creator of the original comic book series, was a big fan of Joy Division and had named the characters Sergeant Albrecht and Captain Hook after bandmates Sumner (who was also known as Bernard Albrecht early in his career) and Hook.[citation needed]

Several groups contributed covers. Nine Inch Nails rendered Joy Division's "Dead Souls", Rollins Band covered Suicide's "Ghost Rider" and Pantera performed Poison Idea's "The Badge".[citation needed]

The bands Medicine and My Life with the Thrill Kill Kult make cameo appearances in the film on stage in the nightclub below Top Dollar's headquarters.[citation needed]

The score consists of original, mostly orchestral music, with some electronic and guitar elements, written for the film by Graeme Revell.[citation needed]

Sequels

[edit]In 1996, a sequel was released, called The Crow: City of Angels. In this film, Vincent Pérez plays Ashe Corven, who, along with his son Danny, is killed by criminals. Ashe is resurrected as a new Crow. The character of Sarah Mohr (now played by Mia Kirshner) reappears in this film and assists Ashe.[61] The film also features Iggy Pop, who, according to the booklet insert for the film's soundtrack, was the producer's first choice for Funboy in the first Crow movie, but he was unable to commit due to his recording schedule. In addition, it also featured the final appearance of Thuy Trang. The band Deftones can be seen playing live in a festival scene and they contributed the song "Teething" to the soundtrack. The film received mostly negative reviews.

The Crow: Stairway to Heaven was a 1998 Canadian television series created by Bryce Zabel and starring Mark Dacascos in the lead role as Eric Draven.[citation needed]

The third film, The Crow: Salvation, was released in 2000. Directed by Bharat Nalluri, it stars Eric Mabius, Kirsten Dunst, Fred Ward, Jodi Lyn O'Keefe and William Atherton. It is loosely based on Poppy Z. Brite's novel The Lazarus Heart. After its distributor cancelled the intended theatrical release due to The Crow: City of Angels' negative critical reception, The Crow: Salvation was released directly to video with mixed reviews.[citation needed]

The fourth film, The Crow: Wicked Prayer, was released in 2005. Directed by Lance Mungia, it stars Edward Furlong, David Boreanaz, Tara Reid, Tito Ortiz, Dennis Hopper, Emmanuelle Chriqui and Danny Trejo. It was inspired by Norman Partridge's novel of the same title. It had a one-week theatrical première on June 3, 2005, at AMC Pacific Place Theatre in Seattle, Washington, before being released to video on July 19, 2005. Like the other sequels, it had a poor critical reception.[citation needed]

The Crow: 2037 was a planned sequel written and scheduled to be directed by Rob Zombie in the late 1990s;[62] however, it was never made.[63][64]

Reboot

[edit]On April 1, 2022, a new attempt at a remake was announced by The Hollywood Reporter, with Bill Skarsgård starring as Eric, Rupert Sanders directing, and Edward R. Pressman and Malcolm Gray co-producing.[65] Days later, the site also reported that FKA Twigs had been cast as Shelly.[66] In July 2022, production on the reboot was reportedly underway in Prague, Czech Republic.[67] By August 26, 2022, Danny Huston was cast as Vincent Roeg.[68] On September 16, 2022, the film wrapped production.[69][70] The film was theatrically released on August 23, 2024, by Lionsgate Films, in the United States.[71]

Home media

[edit]The Crow was first released on VHS and LaserDisc multiple times between 1994 and 1998 in addition to the widescreen DVD on February 3, 1998. The two-disc DVD was released on March 20, 2001, as part of the Miramax/Dimension Collector's Series.[72] On October 18, 2011, The Crow was released on Blu-ray through Lionsgate Pictures who also re-released the DVD format on August 17, 2012.[73] In Japan, the movie was remastered in 4K for a special edition in 2016, although the film's final resolution was capped at 1080p; a 4K edition of the film was released on May 7, 2024.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Ascher-Walsh, Rebecca (May 13, 1994), "How the Crow Flew", Entertainment Weekly, Time Inc., archived from the original on June 6, 2011, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ a b c "Worldwide rentals beat domestic take". Variety. February 13, 1995. p. 28.

- ^ a b Power, Ed (May 21, 2019). "Some Like it Goth: How The Crow Transcended the Tragic, On-Camera Death of Its Star to Become a Superhero Classic". The Independent. Archived from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ a b Kaye, Don (May 13, 2019). "The Superhero Movie Legacy of The Crow". Den of Geek. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ Breihan, Tom (April 20, 2018). "Tragically and fashionably, The Crow turned superhero cinema into a death dance". The A.V. Club. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ Robey, Tim (October 27, 2016). "Brandon Lee, Michael Massee and the 'curse' of The Crow". telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on January 12, 2022. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ a b "The Crow". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ Gallagher, Danny (August 5, 2016). "Hurst Resident and Creator of The Crow, James O'Barr, on the Comic That Made Him Famous". Dallas Observer. Archived from the original on September 2, 2024. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ "CCC09: James O'Barr". CBR. August 10, 2009. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ a b McCracken, Colin (August 24, 2017). "Shadow's Wing: Legacy of The Crow (Exclusive Cast and Crew Interviews)". Medium. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ Levine, Robert (May 30, 1994). "From the Beginning, The Crow Had a Grim Side : Movies: James O'Barr's Comic Book Might Have Adapted Smoothly To The Big Screen, But It Was Spurred By Personal Tragedy". LA Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ Baiss, Bridget (2000). The Making of The Crow. Titan Books. p. 21. ISBN 978-1870048545.

- ^ Baiss, Bridget (2000). The Making of The Crow. Titan Books. p. 24. ISBN 978-1870048545.

- ^ a b Harrington, Richard (May 15, 1994). "The Shadow of The Crow". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 18, 2017. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ Downey, Ryan (October 24, 2017). "10 Things About The Crow You Never Knew". MovieWeb. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ McCarthy, Erin (February 2, 2016). "18 Fascinating Facts About The Crow". Mental Floss. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ Downey, Ryan (October 27, 2009). "The Crow: 15 Years Of Devil's Night". MTV. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ Owen, Luke (June 1, 2020). "The Tragic Story Behind The Death Of Brandon Lee On The Set Of The Crow". FlickeringMyth. Archived from the original on September 2, 2024. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ Travers, Peter. "The Crow". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on April 24, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ "Brandon Lee's Last Interview". Entertainment Weekly. May 13, 1994. Archived from the original on September 23, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ "D.A. Announces Negligence Caused Death of The Crow Actor Brandon Lee". History. April 27, 1993. Archived from the original on April 22, 2023. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ Welkos, Robert W. (April 1, 1993). "Bruce Lee's Son, Brandon, Killed in Movie Accident". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on April 19, 2023. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ a b c Conner & Zuckerman, pp. 35–36

- ^ a b Brown, Dave, "Filming with Firearms", Film Courage, archived from the original on August 8, 2014, retrieved August 15, 2014

- ^ Pristin, Terry (August 11, 1993). "Brandon Lee's Mother Claims Negligence Caused His Death : Movies: Linda Lee Cadwell sues 14 entities regarding the actor's 'agonizing pain, suffering and untimely death' last March on the North Carolina set of 'The Crow'". The Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2010.

- ^ Harris, Mark (April 16, 1993). "The brief life and unnecessary death of Brandon Lee". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 6, 2015. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (January 24, 2012). "UPDATE: F. Javier Gutierrez To Helm Jesse Wigutow-Scripted 'The Crow' Remake". Deadline. Archived from the original on October 23, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2015.

- ^ "As 'The Crow' flies". Entertainment Weekly. October 22, 1993. Archived from the original on September 2, 2024. Retrieved April 13, 2022.

- ^ Friedman, David R. (1996). "The Mysterious Legacy of Brandon Leen". Todays Chiropr. 25: 34–38.

- ^ Cotter, Padraig (June 21, 2019). "The Crow Movie: The Deleted Skull Cowboy Explained". Screenrant. Screen Rant. Archived from the original on December 20, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ Lauren Milici (April 14, 2022). "Why The Crow deserves a comeback". gamesradar. Archived from the original on June 9, 2022. Retrieved May 4, 2022.

- ^ Fox, David J. (May 16, 1994), "'The Crow' Takes Off at Box Office", Los Angeles Times, archived from the original on June 25, 2022, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ "Miramax in hit land". Screen International. August 22, 1997. p. 33.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (October 18, 1994). "'Pulp' claims B.O. title; competitors call it fiction". Daily Variety. p. 1.

- ^ "The Crow". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on November 9, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2015.

- ^ "The Crow (1994)", Box Office Mojo, archived from the original on November 9, 2018, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ "The Crow". 25th Frame. Archived from the original on September 5, 2017. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ "The Crow (1994)". JP's Box-Office. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ "Ворон — дата выхода в России и других странах". KinoPoisk (in Russian). Archived from the original on December 18, 2022. Retrieved August 31, 2019.

- ^ "영화정보". KOFIC. Korean Film Council. Archived from the original on December 25, 2018. Retrieved August 26, 2019.

- ^ "The Crow". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved May 2, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Howe, Desson (May 13, 1994), "'The Crow' (R)", The Washington Post, archived from the original on November 10, 2012, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g Ebert, Roger (May 13, 1994), "The Crow", Chicago Sun-Times, Sun-Times Media Group, archived from the original on August 28, 2022, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ a b Travers, Peter (May 11, 1994), "The Crow", Rolling Stone, Wenner Media, archived from the original on February 22, 2011, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ James, Caryn (May 11, 1994), "Eerie Links Between Living and Dead", The New York Times, archived from the original on September 2, 2024, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ Rainer, Peter (May 11, 1994), "Movie Review: 'The Crow' Flies With Grim Glee", Los Angeles Times, archived from the original on September 2, 2024, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ Welkos, Robert W. (May 11, 1994), "Movie Review: Life After Death: A Hit in the Offing?", Los Angeles Times, archived from the original on September 2, 2024, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g h Berardinelli, James (1994), "Review: the Crow", ReelViews, archived from the original on December 31, 2019, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ a b c d e f g h McCarthy, Todd (April 28, 1994), "The Crow", Variety, Reed Business Information, archived from the original on December 22, 2010, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ Hicks, Chris (September 20, 2001), "The Crow", Deseret News, Deseret News Publishing Company, retrieved March 12, 2011[dead link]

- ^ "The Crow", Montreal Film Journal, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time", Empire, Bauer Media Group, archived from the original on May 13, 2011, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ Ritman, Alex (October 24, 2014). "'The Crow' Remake Aiming for Spring 2015 Production Start". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- ^ Davis, Sandi (January 1, 1995). "Oklahoman Movie Critics Rank Their Favorites for the Year "Forrest Gump" The Very Best, Sandi Declares". The Oklahoman. Archived from the original on July 20, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ Zoller Seitz, Matt (January 12, 1995). "Personal best From a year full of startling and memorable movies, here are our favorites". Dallas Observer.

- ^ Mayo, Mike (December 30, 1994). "The Hits and Misses at the Movies in '94". The Roanoke Times (Metro ed.). p. 1.

- ^ Pickle, Betsy (December 30, 1994). "Searching for the Top 10... Whenever They May Be". Knoxville News-Sentinel. p. 3.

- ^ Elliott, David (December 25, 1994). "On the big screen, color it a satisfying time". The San Diego Union-Tribune (1, 2 ed.). p. E=8.

- ^ Lovell, Glenn (December 25, 1994). "The Past Picture Show the Good, the Bad and the Ugly -- a Year Worth's of Movie Memories". San Jose Mercury News (Morning Final ed.). p. 3.

- ^ "Content International's Film Library", Content International, archived from the original on April 7, 2008, retrieved March 12, 2011

- ^ The Crow: City of Angels at IMDb

- ^ "Zombie Will Write/Direct Next "Crow" Flick". MTV. February 11, 1997. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ "The Crow: 2037 A New World of Gods and Monster | Scripts On The Net". Roteiro de Cinema. September 22, 2008. Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ Anders, Charlie Jane (August 10, 2012). "100 Wonderful and Terrible Movies That Never Existed". Gizmodo. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved November 24, 2012.

- ^ "Bill Skarsgard to Star in 'The Crow' Reboot, Rupert Sanders Directing (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. April 1, 2022. Archived from the original on June 9, 2022. Retrieved April 2, 2022.

- ^ "FKA Twigs Joins Bill Skarsgard in 'The Crow' Reboot". The Hollywood Reporter. April 4, 2022. Archived from the original on April 18, 2022. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ "'The Crow', starring Bill Skarsgård and FKA Twigs, now filming in Prague". The Prague Reporter. July 13, 2022. Archived from the original on September 29, 2022. Retrieved August 4, 2022.

- ^ Taylor, Drew (August 26, 2022). "Danny Huston Joins Bill Skarsgård in 'The Crow' Reimagining". TheWrap. Archived from the original on December 19, 2022. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ "'The Crow' reboot, starring Bill Skarsgård as Eric Draven, wraps production in Prague". The Prague Reporter. September 16, 2022. Archived from the original on October 5, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ Burlingame, Russ (September 30, 2022). "The Crow Reboot Reportedly Wraps Production". ComicBook. Archived from the original on November 26, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (April 9, 2024). "'The Crow' Flies To August, Halle Berry Pic 'Never Let Go' Sets Fall, 'Saw XI' To Slice 2025, 'Best Christmas Pageant Ever' Earlier – Lionsgate Release Date Changes". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 9, 2024. Retrieved April 10, 2024.

- ^ Nichols, Peter M. (September 9, 1994). "Home Video". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

- ^ "The Crow - High-Def Digest". Bluray.highdefdigest.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2012.

Bibliography

[edit]- Conner, Jeff; Zuckerman, Robert (1993), The Crow: The Movie, Kitchen Sink Press, ISBN 0878162852

External links

[edit]- 1994 films

- 1994 action films

- 1994 crime films

- 1994 fantasy films

- 1994 horror films

- 1994 thriller films

- 1994 action thriller films

- 1994 crime thriller films

- 1990s fantasy action films

- 1990s superhero films

- 1990s supernatural films

- 1990s supernatural horror films

- 1990s vigilante films

- 1990s American films

- 1990s English-language films

- American action thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- American fantasy thriller films

- American films about Halloween

- American films about revenge

- American fantasy action films

- American gothic fiction

- American neo-noir films

- American science fantasy films

- American superhero films

- American supernatural horror films

- American supernatural thriller films

- American vigilante films

- Superhero thriller films

- English-language action thriller films

- English-language crime thriller films

- English-language fantasy action films

- English-language fantasy thriller films

- Miramax films

- Dimension Films films

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films based on American comics

- Films directed by Alex Proyas

- Films scored by Graeme Revell

- Films set in Detroit

- Films shot in North Carolina

- Films about corvids

- Resurrection in film

- The Crow films

- Goth subculture

- Superhero horror films

- Summit Entertainment films