Erskine Childers (author)

Erskine Childers | |

|---|---|

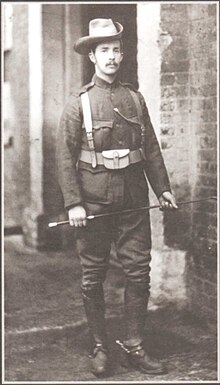

Childers in uniform of the CIV, 1899 | |

| Teachta Dála | |

| In office May 1921 – June 1922 | |

| Constituency | Kildare–Wicklow |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Erskine Childers 25 June 1870 Mayfair, London, England |

| Died | 24 November 1922 (aged 52) Beggars Bush Barracks, Dublin, Ireland |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Resting place | Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Political party | Sinn Féin |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3, including Erskine Hamilton |

| Parent |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Profession |

|

| Known for |

|

Robert Erskine Childers DSC (25 June 1870 – 24 November 1922), usually known as Erskine Childers (/ˈɜːrskɪn ˈtʃɪldərz/[1]), was an English-born Irish nationalist who established himself as a writer with accounts of the Second Boer War, the novel The Riddle of the Sands about German preparations for a sea-borne invasion of England, and proposals for achieving Irish independence.

As a firm believer in the British Empire, Childers served as a volunteer in the army expeditionary force in the Second Boer War in South Africa, but his experiences there began a gradual process of disillusionment with British imperialism. He was adopted as a candidate in British parliamentary elections, standing for the Liberal Party at a time when the party supported a treaty to establish Irish home rule, but he later became an advocate of Irish republicanism and the severance of all ties with Britain. On behalf of the Irish Volunteers, he smuggled guns into Ireland later used against British soldiers in the Easter Rebellion. He had a significant role in the negotiations between Ireland and Britain that culminated in the Anglo-Irish Treaty, but was elected as an anti-Treaty member of the first Irish parliament. He sought an active role in the Irish Civil War (over the acceptance of the terms of the treaty) that followed and was executed by the Irish Free State.

As an author, his most significant work was the novel The Riddle of the Sands, published eleven years before the start of the First World War. Its depiction of a secret German invasion fleet directed against England influenced Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, into strengthening the Home Fleet of the Royal Navy. On the outbreak of the First World War Churchill was instrumental in calling Childers for service in the Royal Navy, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

Childers was the son of British Orientalist scholar Robert Caesar Childers, the father of the fourth president of Ireland Erskine Hamilton Childers, the cousin of British politician Hugh Childers and of Irish nationalist Robert Barton, and the grandfather of the writer and diplomat Erskine Barton Childers and of the former MEP Nessa Childers.

Early life

[edit]Childers was born in Mayfair, London, in 1870.[2][3] He was the second son of Robert Caesar Childers, a translator and oriental scholar from an ecclesiastical family, and Anna Mary Henrietta Barton, from an Anglo-Irish landowning family of Glendalough House, Annamoe, County Wicklow, with interests in France such as the winery that bears their name. When Erskine was six, his father died from tuberculosis and his mother, although at that stage showing no signs of the disease, was confined to an isolation hospital to safeguard her children. She corresponded regularly with Childers until she died from tuberculosis, without having seen her children again, six years later.[4] The five children were sent to the Bartons, the family of their mother's uncle, at Glendalough. Well-treated by his new family, Childers grew up with a strong affection for, and knowledge of, Ireland, albeit, at that point in time, from the comfortable viewpoint of the "Protestant Ascendancy".[5] According to his biographer Michael Hopkinson, it was the personal tension caused by his innate belief in English superiority, in conflict with this new respect for Ireland, which later caused his remarkable conversion to "hard-line Irish republicanism".[2]

He was educated at home by tutors (with his brother Henry and cousin Robert Barton) until the age of ten, when he became a boarder at a preparatory school in England, returning to Glendalough for the holidays.[6] At the recommendation of his grandfather, Canon Charles Childers, in 1883 he was sent to the Haileybury and Imperial Service College. His performance there was initially described as "middling" but he later won school prizes in Latin and in his final year he was made "head of house".[6] There he won an exhibition to Trinity College, Cambridge, where he studied the classical tripos and then law.[7] He distinguished himself as the editor of Cambridge Review, the university magazine. Notwithstanding his unattractive voice and poor debating skills, he became president of the Trinity College Debating Society (known as the "Magpie and Stump"). Although Childers was an admirer of his cousin Hugh Childers, a member of the British Cabinet who had supported the first Irish home rule bill, he spoke vehemently against the policy in college debates, warning that "[Irish] national aspirations were incompatible with our own safety.".[3][8] A sciatic injury sustained while hillwalking in the summer before he went up, which persisted for the rest of his life, left him slightly lame and he was unable to pursue his intention of earning a rugby blue, but he became a proficient rower.[9]

Having stayed an extra year at Cambridge to gain a further degree (in law) Childers briefly entered legal chambers in London as a pupil, the first stage in becoming a barrister.[10] After four months, influenced by his cousin Hugh Childers, he resigned his pupillage and enrolled at a crammer to prepare for the competitive entry examination to become a parliamentary official.[11][12] He was successful and, early in 1895, he became a junior committee clerk in the House of Commons, with responsibility for preparing formal and legally sound bills from the proposals of the government of the day.[13]

Sailing

[edit]

Childers and his brother Henry had kept a small sailboat on Lough Dan, near to Glendalough. From time to time while at Cambridge he had sailed on the Norfolk Broads.[14] With many sporting ventures now closed to him because of his sciatic injury, Childers was encouraged by Walter Runciman, a friend from Trinity College, to take up sailing. After picking up the fundamentals of seamanship as a deckhand on Runciman's yacht, in 1893 with his brother Henry he bought his own boat, the former racing yacht Shulah. This vessel required an experienced crew and was totally unsuitable for novices: they sold it in 1895. His next vessel was the "scrubby little yacht" Marguerite, an 18-foot (5.5 m) half-deck, which he kept at Greenhithe, close to London. After teaching himself navigation and taking lessons in sailboat handling, he undertook trips around the English coast and across the English Channel with his brother Henry.[15] In April 1897 he replaced Marguerite with the larger and more comfortable 30-foot (9.1 m) cutter Vixen; in August that year there was a long cruise in Vixen to the Frisian Islands, Norderney and the Baltic with Henry and Ivor Lloyd Jones, a friend from Cambridge, as crew.[16] These were the adventures he was to fictionalise in 1903 as The Riddle of the Sands, his most famous book and a huge bestseller.[17]

In 1903 Childers was again cruising in the Frisian Islands, in Sunbeam, a boat he bought in syndicate with William le Fanu and other friends from his university days. He was now accompanied by his new wife Molly Osgood.[18] Molly's father, Dr. Hamilton Osgood, arranged for a fine 28-ton yacht, Asgard, to be built for the couple as a wedding gift and Sunbeam was only a temporary measure while Asgard was being fitted out.[19]

Asgard was Childers's last and most famous yacht: in July 1914, he used it to smuggle a cargo of 900 Mauser Model 1871 rifles and 29,000 black powder cartridges to the Irish Volunteers movement at the fishing village of Howth, County Dublin.[3][20] The Asgard was acquired by the Irish government as a sail training vessel in 1961, stored on dry land in the yard of Kilmainham Gaol in 1979, and is now exhibited at The National Museum of Ireland.[21]

War service

[edit]Boer War

[edit]

As with most men of his social background and education, Childers was originally a steadfast believer in the British Empire. Indeed, for an old boy of Haileybury College, a school founded to train young men for colonial service in India, such an outlook on Childers's part was almost inevitable, although, privately, he did not accept completely the "conformist" values of the school.[22][23]

In 1898, as negotiations over the voting rights of British settlers in the Boer territories of Transvaal and Orange Free State failed and the Boer War broke out, Childers needed little encouragement when in December Basil Williams, a colleague at Westminster, suggested that he too should enlist. Williams was already a member of the Honourable Artillery Company (HAC), a volunteer regiment, so at the end of December 1898 Childers joined the HAC.[24]

A battery from the HAC formed part of the hastily constituted City Imperial Volunteers, something of an ad hoc force set up from soldiers from different volunteer regiments, funded by City institutions and provided with the most modern equipment. Childers became a member of the artillery division of this new force, classed as a "spare driver" to care for horses and ride in the ammunition supply train.[25] On 2 February 1900, after three weeks' training, the unit set off for South Africa.[26][24][27] Most of the new volunteers and their officers were seasick and it largely fell to Childers to care for the troop's 30 horses.[28] After a three-week voyage, the company was disappointed not to see immediate action but on 26 June, while escorting a supply train of slow ox-wagons, Childers first came under fire during a three-day skirmish in defence of the column. It was a smartly executed defence of a beleaguered infantry regiment on 3 July that established the worth of his unit and more significant engagements followed.[29]

On 24 August, Childers was evacuated from the front line to hospital in Pretoria, suffering from trench foot. The seven-day journey happened to be in the company of wounded infantrymen from Cork, Ireland, and Childers noted approvingly how cheerfully loyal to Britain the men were, how resistant they were to any incitement in support of Home Rule, and how they had been let down only by the incompetence of their officers.[30] This is a striking contrast to his attitude by the end of the First World War when conscription in Ireland was under consideration and he wrote of "young men hopelessly estranged from Britain and [...] anxious to die in Ireland for Irish liberty.".[31] After a chance meeting with his brother Henry, also suffering from a foot injury, he rejoined his unit, only for it to be dispatched to England on 7 October 1900.[32]

First World War

[edit]Gun running to Ireland

[edit]Childers's attitude to Britain's establishment and politics had become somewhat equivocal by the start of the First World War. He had resigned his membership of the Liberal Party, and with it his hopes of a parliamentary seat, over Britain's concessions to Unionists and a further postponement of Irish self-rule;[3] he had written works critical of British policy in Ireland and in its South African possessions; above all in the Summer of 1914 he had been a member of Mary Spring Rice's committee planning to smuggle guns bought in Germany to supply the Irish Volunteers in the south of Ireland, a "largely symbolic" response to the April 1914 Ulster Volunteers' importation of rifles and ammunition in the Larne gun-running.[33][3] Although in 1914 John Redmond, the leader of the Irish Volunteers, argued that in the case of war his movement would cooperate with the Ulster Volunteers in the defence of Ireland, thus allowing Britain to release troops from the country for the war in Europe, the committee's weapons were used against British soldiers in the Easter Rising of 1916.[34][35]

The members of the committee of eleven included, in addition to Spring Rice: Alice Stopford Green, Roger Casement, Darrell Figgis and Conor O'Brien. Monetary subscriptions were received from other influential figures.[36] O'Brien owned a small yacht Kelpie but Childers considered that his own seagoing experience made him the natural choice to lead the operation. Mindful of the risk that the vessel used to carry the shipment could be confiscated, only when Spring Rice's own boat proved unseaworthy did Childers offer Asgard.[37] With no regard for security, Childers canvassed some acquaintances among British army officers to crew Asgard for the exploit, but only Gordon Shephard of the Royal Fusiliers accepted.[38] Childers and Figgis arranged the weapons' purchase from Hamburg. The landing, with Molly Childers at the helm of Asgard, was on 26 July 1914 at Howth, openly conducted in broad daylight to offer the maximum publicity for the cause.[39] The police and British Army's attempt to intercept the cargo as it was transferred inland led to the Bachelor's Walk massacre of 26 July 1914, when soldiers from the Kings Own Scottish Borderers fired upon uninvolved onlookers.[40]

A week later, when war with Germany was declared, Childers was in Dublin, writing articles for American newspapers to exploit the success of the operation.[41] The knowledge that Childers had made a delivery of rifles and ammunition to Irish nationalists was not in wide circulation, but neither was it a great secret, and the official telegram from the British Admiralty calling Childers to naval service was sent to the Dublin headquarters of the group to which he had made the delivery.[42][43][44]

At that stage, Childers still believed that a self-governing Ireland would take its place as a dominion within the Empire and so he was easily able to reconcile himself to the belief that fighting for Britain in defence of nations under threat from Germany was the right thing to do.[45][3] In mid-August 1914 he responded to the Admiralty telegram and volunteered for service. He received a temporary commission as lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.[46] Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, although hostile to spending money on armaments at the time The Riddle of the Sands was published, later gave the book the credit for persuading public opinion to fund vital measures against the German naval threat, and he was instrumental in securing Childers's recall.[47][48]

Naval service

[edit]Childers's first task was, in reversal of the plot of The Riddle of the Sands, to draw up a plan for the invasion of Germany by way of the Frisian Islands.[49] He was then allocated to HMS Engadine, a seaplane tender of the Harwich Force, as an instructor in coastal navigation to newly trained pilots. His duties included flying as a navigator and observer. A sortie navigating over a familiar coastline in the Cuxhaven Raid (an inconclusive bombing attack on the Cuxhaven airship base on Christmas Day 1914) earned him a mention in despatches.[50][51] In 1915, he was transferred in a similar role to HMS Ben-my-Chree, in which he served in the Gallipoli Campaign and the eastern Mediterranean, earning himself a Distinguished Service Cross.[52]

He was sent back to London in April 1916 to serve in the Admiralty where, because he understood the requirements of airmen, his work included the mundane task of allocating seaplanes to their intended ships.[53][54] It took Childers until autumn of that year to extricate himself and train for service with a new coastal motor-boat squadron operating in the English Channel.[55]

Irish Convention

[edit]In July 1917, the year following the Easter Rising, Horace Plunkett asked for Childers (then a lieutenant-commander in the RNAS serving at a seaplane station at Dunkirk), to be relieved of his operational duties and assigned as secretary to prime minister David Lloyd George's Home Rule Convention. This was an initiative, suggested by Jan Smuts who had used the tactic successfully at the culmination of the Boer War, to convene within Ireland all shades of Irish political opinion to agree a method of government. Plunkett did not have his way, however, as Childers's writings had identified him as a partisan for Home Rule; instead he was appointed as an assistant secretary, with the role of advising the nationalist factions on procedure and presenting their case in formal terms.[56] Talks lasted nine months and at the end Plunkett was obliged to pass on his conclusions that no agreement could be reached: the issues of devolved fiscal powers for the new government, and guarantees to Unionists of the right to nominate a percentage of members of parliament, forcing deadlock. Lloyd George, who was facing the consequences of a German breakout from the trenches in France ("the gravest military crisis of the war"), took no action.[57]

Royal Air Force

[edit]On his return to London in April 1918, Childers found himself transferred into the newly created Royal Air Force, with the rank of major. He was attached to the new Independent Bomber Command as a group intelligence officer, having the responsibility of preparing the navigational briefings for attacks on Berlin. The raids were forestalled by the Armistice and Childers's last assignment was to provide an intelligence assessment of the effects of bombing raids in Belgium.[58] He departed Royal Air Force service on 10 March 1919.[59]

Marriage

[edit]

In autumn 1903, Childers travelled to the United States as part of a reciprocal visit between the Honourable Artillery Company of London and the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts of Boston.[60] Childers had with him a letter of introduction to Dr. Hamilton Osgood, an eminent and wealthy physician in the city, that had been provided by Boston banker Sumner Permain, a friend of Childers's father.[61] Childers was invited to dinner at Osgood's house and there he met Mary Alden Osgood (known as "Molly"), the host's daughter.[a] The well-read republican-minded heiress and Childers found each other congenial company and Childers elected to extend his stay, with much time shared with Molly.[63] The pair were married at Boston's Trinity Church on 6 January 1904. Cousin Robert Barton travelled to Boston to be best man.[64][65]

Childers returned to London with his wife and resumed his position in the House of Commons. His reputation as an influential author gave the couple access to the political establishment, which Molly relished, but at the same time she set to work to rid Childers of his already faltering imperialism.[66] In her turn Molly developed a strong admiration for Britain, its institutions and, as she then saw it, its willingness to go to war in the interests of smaller nations against the great.[67] Over the next seven years they lived comfortably in their rented flat in Chelsea, supported by Childers's salary—he had received promotion to the position of parliamentary Clerk of Petitions in 1903—his continuing writings and, not least, generous benefactions from Dr. Osgood.[68][69]

Molly, despite a severe weakness in the legs following a childhood skating injury,[70] took enthusiastically to sailing, first in Sunbeam and later on many voyages in her father's gift, Asgard.[69] Childers's letters to his wife show the couple's contentment during this time.[3][71] Three sons were born: Erskine in December 1905, Henry, who died before his first birthday, in February 1907, and Robert Alden in December 1910.[72]

Writing

[edit]Childers's first published work was some light detective stories he contributed to The Cambridge Review while he was editor.[73]

In the Ranks of the C.I.V.

[edit]His first book was In the Ranks of the C.I.V., an account of his experiences in the Boer War, but he wrote it without any thought of publication: while serving with the Honourable Artillery Company in South Africa he composed many long, descriptive letters about his experiences to his two sisters, Dulcibella and Constance. They and a family friend, Elizabeth Thompson, daughter of George Smith of the publishing house Smith, Elder, edited the letters into book form.[74][75] The print proofs were waiting for Childers to approve on his return from the war in October 1900 and Smith, Elder published the work in November.[76] It was well-timed to catch the public's interest in the war, which continued until May 1902, and it sold in substantial numbers.[77]

Childers edited his colleague Basil Williams's more formal book, The HAC in South Africa, the official history of the regiment's part in the campaign, for publication in 1903.[78]

Childers's neighbour, Leo Amery, was editor of The Times's History of the War in South Africa, and having already persuaded Basil Williams to write volume four of the work, he used this to persuade Childers to prepare volume five. This profitable commission took up much of Childers's free time until publication in 1907.[79] It drew attention to British political and military errors and made unfavourable contrast with the tactics of the Boer guerrillas.[80]

The Riddle of the Sands

[edit]In January 1901, Childers started work on his novel, The Riddle of the Sands,[81] but initially progress was slow;[82] it was not until winter of that year that he was able to tell Williams, in one of his regular letters, of the outline of the plot. At the end of the following year, after a hard summer of writing, the manuscript went to Reginald Smith at Smith Elder. But in February 1903, just as Childers was hoping to return to editing The HAC in South Africa, Smith sent back the novel, with instructions for extensive changes. With the help of his sisters, who cross-checked the new manuscript pages against the existing material,[74] Childers produced the final version in time for publication in May 1903.[83] Based on his own sailing trips with his brother Henry along the German coast, it predicted war with Germany and called for British preparedness. There has been much speculation about which of Childers's friends was the model for "Carruthers" in the novel: he is based not on Henry Childers but on the author's long-term friend the yachting enthusiast Walter Runciman. "Davies", of course, is Childers himself.[84] Widely popular, the book has never gone out of print.[85] The Observer included the book on its list of "The 100 Greatest Novels of All Time".[86] The Telegraph listed it as the third best spy novel of all time.[87] It has been called the first spy novel (a claim challenged by advocates of Rudyard Kipling's Kim, published two years earlier), and enjoyed immense popularity in the years before World War I.[88] It was an extremely influential book: Winston Churchill later credited it as a major reason that the Admiralty decided to establish naval bases at Invergordon, Rosyth on the Firth of Forth and Scapa Flow in Orkney.[48] It was also a notable influence on authors such as John Buchan and Eric Ambler.[89]

"Cavalry controversy"

[edit]Motivated by his expectation of war with Germany, Childers wrote two books on cavalry warfare, both strongly critical of what he saw as outmoded British tactics. Everyone agreed that cavalry should be trained to fight dismounted with firearms, but military traditionalists wanted cavalry still to be trained as the arme blanche, bringing shock tactics to bear by charging the enemy with lance and sabre. Training in the traditional, mounted tactics had been reestablished after the modernising reformer Field Marshal Roberts retired in 1904, when General Sir John French, who had commanded successful cavalry charges at the Battle of Elandslaagte and the relief of Kimberley, was promoted to the senior levels of the army.[90] Childers's War and the Arme Blanche (1910) carried a foreword from Roberts, and recommended that cavalry, instead of charging the enemy positions, should "make genuinely destructive assaults upon riflemen and guns" by firing from the saddle.[91][92] French, among the traditionalists, responded in defence of the old tactics in his preface (in an unlikely alliance) to Prussian general Friedrich von Bernhardi's Cavalry in War and Peace (1910).[93] This allowed Childers to counter with German Influence on British Cavalry (1911), an "intolerant" rejoinder to the criticisms of his book made by French and Bernhardi.[3][94][95]

The Framework of Home Rule

[edit]It was as a prospective Liberal Party candidate for Parliament that Childers wrote his last major book: The Framework of Home Rule (1911).[96] Childers's principal argument was an economic one: that an Irish parliament (there would be no Westminster MPs) would be responsible for making fiscal policy for the benefit of the country, and would hold "dominion" status, in the same detached way in which Canada managed its affairs.[97] His arguments were based in part on the findings of the Childers Commission of the 1890s, which was chaired by his cousin, Hugh Childers. Erskine Childers consulted Ulster Unionists in preparing Framework and wrote that their reluctance to accept the policy would easily be overcome.[98][99] Although it represented a major change from the opinions Childers had previously held, enacting Irish Home Rule was the Liberal government's policy at the time.[100]

An emerging problem was that the book assumed fiscal independence and self-government for the whole island of Ireland, including the wealthier and more industrialised counties around Belfast. During his research Childers naïvely came to believe that the opposition of the unionists in the region was mainly bluff, or that the industrialists' entrepreneurial spirit would easily overcome any monetary disadvantages they might initially suffer.[101] In this he was wrong: this disparity (together with the largely Protestant unionists' fear of Catholic "rule from Rome") was a significant contributor to the failure of the 1917 Home Rule Convention and, ultimately, to the Partition of Ireland of 1921.[102]

Reception for the work, in both England and Ireland, was positive, although the Belfast Newsletter warned that the pretensions and influence of the Catholic church would endanger acceptance of any such proposals. The Manchester Guardian took issue with Childers's optimistic comparisons with other British overseas territories, warning that the manner of colonial rule over indigenous populations, effective in distant parts of the empire, would be impossible to implement in Ireland.[101] This point was taken up by several other reviewers as an indication of a tendency in Childers towards white supremacy. For example: Robert Lynd of the Daily News wrote that Childers was drawing on the argument that "the essential Irish character[…]is the same as the character of other white races," and the Glasgow Herald wondered why Childers would confine the benefits of freedom only to the "white races".[103]

Conversion

[edit]There was no single incident which was responsible for Childers's conversion from supporter of the British Empire to his leading role in the Irish revolution. In his own words, delivered on 8 June 1922 while a Teachta Dála (Deputy) at the Dáil Éireann, replying to a motion of censure: "[...] by a process of moral and intellectual conviction I came away from Unionism into Nationalism and finally into Republicanism. That is a simple story."[104] There was a growing conviction, later turning to "fanatical obsession" (as his critics and friends both would suggest[105][106]) that the island of Ireland should have its own government.[107]

An early source of disillusionment with Britain's imperial policy was his view that, given more patient and skilful negotiation, the Boer War could have been avoided.[108] His friend and biographer Basil Williams noticed his growing doubts about Britain's actions in South Africa while they were on campaign together: "Both of us, who came out as hide-bound Tories, began to tend towards more liberal ideas, partly from the [...] democratic company we were keeping, but chiefly, I think, from our discussions on politics and life generally."[109] Molly Childers, brought up in a family that traced its roots to the Mayflower, also influenced her husband's outlook on the right of Britain to rule other countries.[66]

The ground was well prepared, then, when in the summer of 1908 he and his cousin Robert Barton took a holiday motor tour inspecting Horace Plunkett's agricultural co-operatives in the south and west of Ireland—areas ravaged with poverty. "I have come back", he wrote to Basil Williams, "finally and immutably a convert to Home Rule ... though we both grew up steeped in the most irreconcilable sort of Unionism."[110]

In the autumn of 1910 Childers resigned his post as Clerk of Petitions to leave himself free to join the Liberal Party, with its declared commitment to Home Rule: the Liberal Party relied on Irish Home Rule MPs for its Commons majority.[100] In a lecture delivered in Dublin in March 1912, Childers described the benefits to Ireland, and opportunities for nationalists, from the Liberal party's proposed new home rule bill (placed before the UK parliament on 11 April 1912).[111] Childers's narrative explaining the Liberal's proposals was well received, but he noted that his audience reacted "coldly" to any suggestion that, post-independence, Ireland could participate in the future of the Empire.[112]

Childers secured for himself the candidature in one of the parliamentary seats in the naval town of Devonport. As the well-known writer of The Riddle of the Sands, with its implied support for an expanded Royal Navy, Childers could hardly fail to win the vote whenever the next election was called. But in response to threats of civil war from the Ulster Unionists, the party began to entertain the idea of removing some or all of Ulster from a self-governed Ireland. Childers abandoned his candidacy and left the party.[3]

The Liberals' Home Rule Bill, introduced in 1912, would eventually pass into law in 1914, but was immediately—by a separate Act of Parliament—shelved for the duration of the Great War, which had just begun. The Amending Bill to exclude six of the nine counties of Ulster for an indeterminate period was eliminated altogether.[113][114] On Easter Monday of 1916 the Irish Volunteers (who had taken possession of the rifles Childers had delivered at Howth in 1914) mounted a violent uprising (the "Easter Rising") in protest at the delay. Its harsh suppression using artillery, and the ruthless prosecution of the captured ringleaders, dismayed Childers and he did not regret that the rifles from the Howth landing had been used against British soldiers.[115]

Home Rule

[edit]In the United Kingdom General Election of November 1918 Sinn Féin secured 73 of the 105 Irish seats. The party's policy was to refuse to take up their places in the Westminster parliament and in January 1919 they set up their own assembly, the Dáil Éireann, in Dublin.[116] In March 1919 Childers presented himself at the Dublin office of Sinn Féin and offered his services. Robert Brennan introduced Childers to Arthur Griffith, the founder of Sinn Féin who said of Childers at that time: "He's a good man to have. He has the ear of a big section of the English people".[117] Desmond FitzGerald, responsible for Sinn Féin publicity, recognised that an English author with a wide following would be useful and he suggested that Childers should assist him. FitzGerald and Robert Barton arranged for Childers to be introduced to the Irish military leader Michael Collins, who in turn introduced him to Éamon de Valera, the President of Sinn Féin.[116] After recuperating from a severe attack of influenza at Glendalough, Childers returned to London, where he could more effectively lobby on behalf of Sinn Féin.[118] He rejoined Molly at their Chelsea flat, while also renting a house in Dublin. Molly was reluctant to remove to Dublin: she was mindful of her sons' education at English schools and she believed that she and her husband could best serve the Nationalist cause by influencing opinion in London. She eventually gave up their London home of fifteen years to settle in Dublin at the end of 1919.[119]

A month after returning to London, Childers received an invitation to meet the Sinn Féin leaders in Dublin. Anticipating an offer of a major role, Childers hurried to return but, apart from Collins, he found the leadership wary, or even hostile. Arthur Griffith, in particular, considered him as at best a renegade and traitor to Britain, or at worst as a British spy.[120] He was appointed to join the Irish delegation from the as-yet-unrecognised Irish state to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919. His unpromising role, as Childers saw it, was to advance the cause of Irish self-determination by reminding delegates of the ideals of freedom over which Britain had gone to war.[121] The initiative proved unavailing, and he returned once again to London.[120]

In 1920 he published Military Rule in Ireland, a pamphlet made up of eight articles from the left-wing London Daily News appearing between March and May 1920,[122] each a strong attack on British army operations in Ireland.[123] At the 1921 elections, he was elected (unopposed) to the Second Dáil as Sinn Féin member for the Kildare–Wicklow constituency,[124] and published the pamphlet Is Ireland a Danger to England? The strategic question examined, rebutting British prime minister Lloyd George's claim that an independent Ireland risked Britain's security.[125]

In February 1921 Childers became editor of the Irish Bulletin and Director of Publicity for the Dáil after the arrest of Desmond FitzGerald.[126] He stood as a Sinn Féin (anti-treaty) candidate at the 1922 general election but lost his seat.[127]

Irish War of Independence

[edit]From 1919 the Irish Republican Army (IRA), notionally under the command of Irish defence minister Cathal Brugha, regarded itself as a legitimate force answerable to the Dáil Éireann. It began a series of attacks on British institutions in Ireland.[128] The "Irish War of Independence", as the series of IRA strikes (and British reprisals, such as those by the "Black and Tans") became known,[129] lasted until July 1921, when Éamon de Valera and British prime minister David Lloyd George agreed a truce.[130] Childers had exercised more influence on the British change of heart than he knew: his reporting in the United States had strengthened sympathy for the Nationalist cause and in turn the US government applied pressure on the British administration.[131]

Treaty negotiations

[edit]

On 12 July 1921 de Valera and a small group, including Childers as secretary, travelled to London for discussions with Lloyd George.[132] De Valera submitted Lloyd George's proposals to the Dáil and the outcome was an Irish delegation sent to London on 7 October 1921 for formal talks to negotiate the terms of a treaty. De Valera did not go but he insisted against strong opposition that Childers, in whom he had particular faith,[133] should remain secretary.[134][135] Protracted negotiations continued until agreement was reached on 5 December 1921.[136]

Childers was vehemently opposed to the final draft of the agreement, even when the clauses that required Irish leaders to take the Oath of Allegiance to the British monarch had been redefined to remove any real authority of the Crown in Ireland.[137][138] As secretary to the delegation (rather than a full delegate) his determined resistance to the terms offered by the British was overruled, notwithstanding his attempts "forever trying to manipulate the Irish delegates into uncompromising positions".[139] At the termination of the talks, Lloyd George noted a "sullen" Childers, disappointed that his "tenacious [and] sinister" attempts to wreck the negotiations had failed.[140] Historian Frank Pakenham was less critical: many of the British concessions that had permitted the Irish delegation eventually to sign the document had been introduced at Childers's instigation.[141]

The Anglo-Irish treaty agreement was presented to the Dáil and debated between December 1921 and January 1922.[142] Childers denounced it, declaring that by accepting compromise Ireland had of its own volition relinquished its independence. Arthur Griffith, a member of the delegation who had pragmatically conceded to Britain over the Oath of Allegiance, alleged that Childers was a secret agent of Britain now working to wreck the agreement and destabilise the new state. The Dáil voted to adopt the terms by the narrow majority of 64 to 57.[143][144]

Onset of civil war

[edit]The treaty with Britain broadened the division between Sinn Féin and the "Irregulars" a breakaway anti-treaty faction of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) led by Cathal Brugha.[145] Ireland descended into civil war on 28 June 1922, when government forces, using borrowed British artillery, bombarded the Four Courts, once Ireland's judicial centre but now used as the military headquarters of the IRA.[146]

Fugitive

[edit]

During the civil war Childers was on the run with the anti-treaty forces in County Cork and County Kerry. The author Frank O'Connor was involved with Childers during the later part of the Civil War and gave a colourful picture of Childers's activities. According to O'Connor, Childers was ostracised from the anti-treaty forces and referred to as "that bloody Englishman", with untrained military officers, newly created from "country boys", ignoring Childers's considerable experience as a professional soldier.[147] The high command of the anti-treaty forces, too, distanced themselves from Childers.[148] His lowly rank was "Staff Captain, Southern Command, IRA".[149] Although the headquarters of the rebel army was at Macroom, County Cork only for a short time, while there Childers was able to produce southern editions of An Phoblacht which, as it was produced in the "war zone", he called Republican War News. His clandestine printing press was moved between safe houses by pony and trap.[149][150]

Childers's reporting of the skirmishes allowed Kevin O'Higgins, the provisional government's justice minister, to declare that Childers was in fact the leader of the rebels, and indeed nothing less than the instigator of the civil war itself, through his resistance to compromise with England.[151][152] Frank O'Connor saw that the government's intention was to "prepare the way for [Childers's] execution".[153] The death in an ambush of Michael Collins intensified the desire of Free State authorities for retribution, and on 28 September 1922, the Dáil introduced the Army Emergency Powers Resolution, establishing martial law powers and listing carrying firearms without a licence a capital offence.[154]

Early in November 1922, after his printing press had fallen down a hillside and become lost in a bog,[155] Childers decided that the cause would be better served if he were at de Valera's side as he attempted to rally the anti-treaty forces. Accordingly he set off by bicycle (in company with David Robinson, also on the run[156]) on the 200-mile (320 km) journey from Cork to his old home at Glendalough, as a staging post before meeting De Valera in Dublin. On 10 November Free State forces, possibly informed by an estate worker, burst into the house and arrested him.[157][158] Robinson had hidden himself in a cellar and was not captured.[156] Upon hearing of Childers's capture Winston Churchill expressed his satisfaction, referring to Childers as "the mischief-making, murderous renegade".[159] Years later, Churchill's opinion of Childers seems to have softened referring to him as a "man of distinction, ability and courage[...]who had shown daring and ardour against the Germans in the Cuxhaven raid on New Year's Day 1915[...]."[160]

Trial and appeal

[edit]

Childers was put on trial by a military court on the charge of possessing a small Spanish-made "Destroyer" .32 calibre semi-automatic pistol on his person in violation of the Emergency Powers Resolution.[156][161] The gun had been a gift from Michael Collins before Collins became head of the pro-treaty Provisional Government.[148] Childers was convicted by the military court and sentenced to death on 20 November 1922.[162]

Childers appealed against the sentence, and this was heard the next day by Judge Charles O'Connor, who said he lacked jurisdiction because of the civil war:

The Provisional Government is now de jure as well as de facto the ruling authority bound to administer, to preserve the peace and to repress by force, if necessary, all persons who seek by violence to overthrow it ... He [Childers] disputes the authority of the [military] Tribunal and comes to this Civil Court for protection, but its answer must be that its jurisdiction is ousted by the State of War which he himself has helped to produce.[163][164]

Childers's lawyer appealed to the Supreme Court, but before it was even accepted by the court and listed as an appealable case, he was put to death.[165][166]

Execution

[edit]

Childers was executed on 24 November 1922 by firing squad at the Beggars Bush Barracks in Dublin. Before his execution he shook hands with the firing squad.[3] He obtained a promise from his then 16-year-old son, the future President of Ireland, Erskine Hamilton Childers, to seek out and shake the hand of every man who had signed his death sentence.[167] His final words, spoken to the firing squad, were: "Take a step or two forward, lads, it will be easier that way."[168]

Childers's body was buried at Beggars Bush Barracks until 1923, when it was exhumed and reburied in the republican plot at Glasnevin Cemetery.[3]

Legacy

[edit]Winston Churchill, who had exerted pressure on Michael Collins and the Free State government to make the treaty work by crushing the rebellion, expressed the view that, "No man has done more harm or shown more genuine malice or endeavoured to bring a greater curse upon the common people of Ireland than this strange being, actuated by a deadly and malignant hatred for the land of his birth."[169] By contrast, Éamon de Valera said of him, "He died the Prince he was. Of all the men I ever met, I would say he was the noblest."[170]

On 23 November 2022 the Irish national broadcaster RTÉ transmitted a television programme to mark the centenary of Childers's execution. While acknowledging the importance within Ireland of his political and revolutionary achievements, and his role as "an active propagandist" for the revolution, it contended that his fame beyond Ireland now rests only on his novel The Riddle of the Sands.[171]

It was the express wish of Molly Childers, upon her death in 1964, that the extensive and meticulous collection of papers and documents from her husband's in-depth involvement with the Irish struggles of the 1920s should be locked away until 50 years after his death. In 1972, Erskine Hamilton Childers started the process of finding an official biographer for his father. In 1974, Andrew Boyle (previous biographer of Brendan Bracken and Lord Reith amongst others) was given the task of exploring the vast Childers archive, and his biography of Robert Erskine Childers was finally published in 1977.[172]

In December 2021 An Post, the Irish national post office, issued a postage stamp to mark the centenary of Childers's execution. Also available was a "first day cover", with an image of the Asgard.[173]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Burke Wilkinson of the Massachusetts Historical Society suggests that their first meeting was at a public reception for the HAC, where Molly had contrived to be seated next to Childers.[62]

References

[edit]- ^ Olausson & Sangster 2006, p. 71.

- ^ a b Hopkinson, Michael A. "Childers, (Robert) Erskine". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Childers, (Robert) Erskine (1870–1922)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 27.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 6.

- ^ a b Ring 1996, pp. 29–31.

- ^ "Childers, Robert Erskine (CHLS889RE)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 49–61.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 21.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 39.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 64.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 19 "The duties included drafting and continually re-drafting proposed legislation ... carefully selecting words and phrases to comply with the compromises reached by the politicians.".

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 45.

- ^ Piper 2003, pp. 22–27.

- ^ Piper 2003, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Fowler, Carol (December 2003). "Erskine Childers's log books". Sailing Today. National Maritime Museum. Archived from the original on 23 January 2009. Retrieved 23 December 2008.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 94.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 125.

- ^ Ball 2006, p. 153.

- ^ "Asgard At The National Museum". RTÉ Archives. Raidió Teilifís Éireann. Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Buettner 2005, p. 167.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 40–43.

- ^ a b Piper 2003, pp. 39–42.

- ^ Childers 1901, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Reader 1988, p. 13.

- ^ "The War in South Africa". The Times. No. 36057. London. 5 February 1900. p. 9.

- ^ Childers 1901, p. 13.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 48.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 55.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 239.

- ^ Childers 1901, p. 289.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 123.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 175.

- ^ FitzPatrick 1997, p. 386.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 187–188.

- ^ Ring 1996, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 126.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 145.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 147.

- ^ Ring 1996, pp. 152–153.

- ^ For example, G. M. Trevelyan, an acquaintance from Trinity College Dublin, wrote to Childers a letter of congratulation on his exploit: Boyle 1977, p. 329

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 140.

- ^ In later years Childers's enemies in the new Irish Parliament cited this telegram as evidence that he had always been a British agent: Boyle 1977, pp. 196, 256, 308.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 151.

- ^ "Admiralty". London Gazette (28876): 6594. 21 August 1914.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 77.

- ^ a b Knightley 2003, p. 17.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 197.

- ^ "Cuxhaven Raid". The Times. London. 19 February 1915. p. 6.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 153.

- ^ "Naval Honours. Awards for Patrol and Air Services". The Times. London. 23 April 1917. p. 4.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 173.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 179.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 188.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 235–237.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 242–243.

- ^ "Royal Air Force". The London Gazette. No. 31458. 15 July 1919. p. 9003.

- ^ "The Londoners in Boston". The New York Times. 4 October 1903. p. 1.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 19.

- ^ Wilkinson, Burke (1974). "Erskine Childers: The Boston Connection". Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society. 86: 53–63. ISSN 0076-4981. JSTOR 25080758. Archived from the original on 25 October 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- ^ McCoole 2003, p. 147.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 88.

- ^ Dempsey, Pauric J.; Boylan, Shaun. "Barton, Robert Childers". Dictionary of Irish Biography. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. Archived from the original on 31 October 2022. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ a b Boyle 1977, pp. 124–126.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 238.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 138.

- ^ a b Ring 1996, pp. 94–95.

- ^ McCoole 2003, p. 30.

- ^ Wilkinson 1976, p. 76.

- ^ Piper 2003, pp. 94, 101.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 70.

- ^ a b "Thompson, Henry Yates". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 61.

- ^ "New and recent books". London Daily News. 21 November 1900. p. 6.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 63.

- ^ Williams & Childers 1903.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 115.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 129–131.

- ^ Childers 1903.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 71.

- ^ "Smith Elder and Co's new books". The Times. No. 37105. 12 June 1903. p. 8.

- ^ Piper 2003, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Drummond 1992, Introduction.

- ^ McCrum, Robert (12 October 2003). "The 100 greatest novels of all time". Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on 21 June 2008. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "The 20 best spy novels of all time". The Telegraph. 3 August 2016. Archived from the original on 12 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ Fulton, Colin Roderick (26 October 2016). "The best early spy novels". Strand Magazine. London. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "Eric Ambler Dies; Lauded as Father of Modern Spy Thriller". The Washington Post. 25 October 1998. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2012 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ Beckett & Simpson 1985, p. 48.

- ^ Childers 1910, p. 1.

- ^ Badsey 2008, pp. 223–224.

- ^ von Bernhardi 1910.

- ^ Childers 1911a, p. 15.

- ^ Piper 2003, p.103: "For the first time we see Erskine the fanatic, the least pleasant aspect of his character; an aspect that was to become all too dominant when his naturally obsessive nature became involved with Ireland.".

- ^ Childers 1911b.

- ^ Kendle 1989, p. 264.

- ^ Boyce & O'Day 2001, p. 152.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 165–169).

- ^ a b Clarke 1990, p. 294.

- ^ a b Ring 1996, pp. 121–123.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 193.

- ^ Robert Lynd (12 December 1911) Daily News, "A Book of the Day", page 3; Glasgow Herald, (28 December 1911) "Home Rule Idealised", page 9, both references quoted in Peatling, G. K. (January 2005). "The Whiteness of Ireland Under and After the Union". Journal of British Studies. 44 (1): 115–133. doi:10.1086/424982.

- ^ Tuairisg Oifigiúil (Official Report): For Periods 16th August 1921, to 26th August 1921, and 28th February 1922 to 8th June 1922 (Report). Dublin: Stationery Office. 1922. p. 503.

- ^ This was the reluctant opinion, for example, of Childers's long-time friend and colleague Basil Williams: Piper 2003, p. 234

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 206: "By this time [sc. his arrest] Erskine's opinions were more extreme than most members of Sinn Féin [...]The fact is that Erskine Childers went to extremes with everything he did."

- ^ Edwards, Robert Dudley; Moody, Theodore William (1981). "Defence and the role of Erskine Childers". Irish Historical Studies. 21, 22: 251.

- ^ McMahon 1999, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Williams 1926, p. 18.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 109.

- ^ Childers 1912, p. 32.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 124.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 184–185.

- ^ "Vital importance of national unity. The Amending Bill postponed". The Times. No. 40590. London. 31 July 1914. p. 12.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 222.

- ^ a b Ring 1996, pp. 204, 207.

- ^ Brennan, Robert (1950). Allegiance. Dublin: Brown and Nolan Ltd. p. 245.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 196.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 253–254.

- ^ a b Piper 2003, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 251.

- ^ Childers, Erskine (29 March 1920). "Military Rule in Ireland. What It Means". Daily News. London. p. 6 – via British Newspaper Archive. Subsequent parts I–VII published 7, 12, 14, 19, 27 April, ?, and 20 May 1920.

- ^ Childers 1920b.

- ^ "Erskine Robert Childers". Oireachtas Members Database. Archived from the original on 8 November 2018. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ Bourke, Richard (30 April 2022). "Erskine Childers, Is Ireland a Danger to England?". The Political Thought of the Irish Revolution: 331–340. doi:10.1017/9781108874465.031. ISBN 9781108874465.

- ^ Mac Donncha, Mícheál (12 November 2009). "Remembering the Past: The Irish Bulletin". An Phoblacht. Archived from the original on 4 September 2023. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- ^ "Robert Erskine Childers". ElectionsIreland.org. Archived from the original on 18 October 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 258.

- ^ Hopkinson 2002, pp. xvii, xix.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 275–276.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 271.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 243.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 235.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 209.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 248.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 264.

- ^ "[…]swearing allegiance first to the constitution of the Irish Free State, secondly to the crown in virtue of the common citizenship between the two countries[…]" Lee 1989, p. 50

- ^ Pakenham 1921, pp. 112–114.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 213.

- ^ Ring 1996, pp. 264–265.

- ^ Pakenham 1921, pp. 189–191.

- ^ "The Treaty Debates". www.oireachtas.ie. Houses of the Oireachtas. 28 August 2023. Archived from the original on 20 April 2023. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 218.

- ^ "Motion of Censure". Dáil Éireann. Archived from the original on 19 February 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2023.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 272.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 220.

- ^ O'Connor 1960, p. 157.

- ^ a b Boyle 1977, p. 15.

- ^ a b Ring 1996, p. 276.

- ^ Barrett, Anthony. "The Media War: Robert Erskine Childers in West Cork". Irish History Online. Archived from the original on 14 October 2022. Retrieved 14 October 2022.

- ^ Ring 1996, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Piper 2003, pp. 222–223.

- ^ O'Connor 1960, p. 162.

- ^ Campbell 1994, p. 196.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 312.

- ^ a b c Wilkinson 1976, pp. 220–223.

- ^ Piper 2003, p. 225.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 299, 317–319.

- ^ Bromage, Mary (1964), Churchill and Ireland, University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, IL, pg 96, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 64-20844

- ^ Churchill 1955, p. 370.

- ^ Siggins, Lorna (18 October 1995). "Pixilated Pistol puts in a timely reappearance". The Irish Times. p. 1.

- ^ Ring 1996, pp. 286–287.

- ^ Application of Childers; High Court, 22 November 1922

- ^ "The Childers Case". The Times. No. 43197. 24 November 1922. p. 14.

- ^ Ring 1996, p. 286.

- ^ Ranelagh 1999, p. 206.

- ^ Peter Stanford (8 November 1976). "On Soundings". Time. Archived from the original on 25 June 2009. Retrieved 8 August 2008.

- ^ Boyle 1977, p. 25.

- ^ From a speech given by Winston Churchill, 11 November 1922 in Dundee."Mr Churchill at Dundee". The Times. 13 November 1922. p. 18.

- ^ Jordan 2010, p. 127.

- ^ Byrne, Donal (23 November 2022). "The execution of Robert Erskine Childers". RTÉ News. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

- ^ Boyle 1977, pp. 8–10.

- ^ "First Day Cover (Centenary of the death of Erskine Childers)". An Post. Archived from the original on 2 September 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2023.

Sources

[edit]- Badsey, Stephen (July 2008). Doctrine and Reform in the British Cavalry 1880–1918. Farnham, England: Ashgate. ISBN 9780754664673.

- Ball, Robert W. D. (2006). Mauser Military Rifles of the World. Iola, WI: Krause. ISBN 9780896892965.

- Beckett, Ian; Simpson, Keith (1985). A nation in arms: a social study of the British army in the First World War. Manchester University Press. p. 48. ISBN 9780719017377.

- von Bernhardi, Friedrich (1910). Cavalry in War and Peace. Translated by George Bridges. London: Hodder & Stoughton. OCLC 360808.

- Boyce, David George; O'Day, Alan (2001). Defenders of the Union: A Survey of British and Irish Unionism Since 1801. London: Routledge. p. 152. ISBN 9780415174213.

- Boyle, Andrew (1977). The riddle of Erskine Childers. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 9780091284909.

- Buettner, Elizabeth (2005). Empire Families. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199287659.

- Campbell, Colm (1994). Emergency law in Ireland, 1918–1925. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198256755.

- Childers, Erskine (1901). In The Ranks of the C. I. V. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- — (1903). The Riddle of the Sands : A Record of Secret Service Recently Achieved. London: Smith, Elder & Co. OCLC 3569143.

- — (1910). War and the Arme Blanche. London: Edward Arnold. OCLC 3644148.

- — (1911a). German Influence on British cavalry. London: Edward Arnold. OCLC 11627879.

- — (1911b). The Framework of Home Rule. London: Edward Arnold. OCLC 906176236.

- — (2 March 1912), The form and purpose of Home Rule, Dublin: Edward Ponsonby, OCLC 7485421

- — (1920b). Military Rule in Ireland. Dublin: Talbot Press. OCLC 16043760.

- Clarke, Peter (1990). "Government and Politics in England: realignment and readjustment". In Haigh, Christopher (ed.). The Cambridge Historical Encyclopedia of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. [1]. ISBN 9780521395526.

- Churchill, Winston (1955). The World Crisis—The Aftermath. Vol. IV. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. ISBN 9781472586957.

- Coogan, Tim Pat (1994). The IRA: A History. Niwot, Colorado: Roberts Rinehart. ISBN 9781879373679.

- Costello, Peter (1977), The Heart Grown Brutal: The Irish Revolution in Literature from Parnell to the Death of Yeats, 1891–1939, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 9780847660070.

- Cox, Tom (1975). Damned Englishman: A Study Of Erskine Childers (1870–1922). Exposition Press. ISBN 9780682478212.

- Drummond, Maldwin, ed. (1992). The Riddle of the Sands. London: The Folio Society.

- FitzPatrick, David (1997). Thomas Bartlett, Keith Jeffery (ed.). A Military History of Ireland. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521629898.

- Hopkinson, Michael (2002). The Irish War of Independence. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773524989.

- Jordan, Anthony J (2010). Éamon de Valera, 1882–1975 : Irish : Catholic : visionary. Dublin: Westport Books. ISBN 9780952444794.

- Kendle, John (1989). Ireland and the federal solution. Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773506763.

- Knightley, Phillip (2003). The Second Oldest Profession: Spies and Spying in the Twentieth Century. London: Pimlico. ISBN 9780140106558.

- Lee, J. J. (1989). Ireland, 1912-1985 : politics and society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521377416.

- McCoole, Sinéad (2003). No Ordinary Women: Irish Female Activists in the Revolutionary Years 1900–1923. Madison WI: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9781847177896.

- McInerney, Michael (1971). The Riddle Of Erskine Childers: Unionist & Republican. E & T O'Brien. OCLC 7092164.

- McMahon, Deirdre (1999). "Ireland and the Empire-Commonwealth, 1900–1948". In Brown, Judith M; Louis, William (eds.). The Oxford History of the British Empire. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 147–148. ISBN 9780199246793.

- O'Connor, Frank (1960). An Only Child And My Father's Son: An Autobiography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780330304207.

- Olausson, Lena; Sangster, Catherine M. (2006). Oxford BBC guide to pronunciation: the essential handbook of the spoken word. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780192807106.

- Pakenham, Frank (1921). Peace By Ordeal. Jonathan Cape. ISBN 9787800337031.

- Piper, Leonard (2003). Dangerous waters : the life and death of Erskine Childers. Hambledon. ISBN 9781852853921. Also known as The tragedy of Erskine Childers.

- Popham, Hugh (1979). A Thirst For The Sea: Sailing Adventures of Erskine Childers. Stanford Maritime. ISBN 9780540071975.

- Ranelagh, John (1999). A short history of Ireland (2 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521469449.

- Reader, William (1988). At Duty's Call: A Study in Obsolete Patriotism. Manchester, England: Manchester University Press. ISBN 9780719024092.

- Reid, Walter (2006). Architect of Victory: Douglas Haig. Birlinn Ltd, Edinburgh. ISBN 9781841585178.

- Ring, Jim (1996). Erskine Childers: A Biography. John Murray. ISBN 9780719556814.

- Sheffield, Gary (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. Aurum, London. ISBN 9781845136918.

- Wilkinson, Burke (1976). The Zeal of the Convert. Washington: R. B. Luce. OCLC 473681951.

- Williams, Basil; Childers, Erskine (1903). The H.A.C. in South Africa : a record of the services rendered in the South African War by members of the Honourable Artillery Company. London: Smith Elder. OCLC 13508383.

- Williams, Basil (1926). Erskine Childers, 1870–1922: A Sketch. London: Women's Printing Society. OCLC 34705727.

External links

[edit]- Works by Erskine Childers in eBook form at Standard Ebooks

- Works by Erskine Childers at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Erskine Childers at the Internet Archive

- Works by Erskine Childers at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Erskine Childers at Open Library

- Free ebooks of The Riddle of the Sands and In the Ranks of the C.I.V., optimised for printing, plus selected Childers bibliography

- Childers's rebuttal to the Dail in 1922 that he had served in the British Secret Service.

- "Newsreel Movie Footage of Robert Erskine Childers". London: British Pathé. 1922.

- "Archival material relating to Erskine Childers". UK National Archives.

- . . Dublin: Alexander Thom and Son Ltd. 1923. p. – via Wikisource.

- 1870 births

- 1922 deaths

- British non-fiction writers

- Early Sinn Féin TDs

- People from Mayfair

- People educated at Haileybury and Imperial Service College

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Honourable Artillery Company soldiers

- British Army personnel of the Second Boer War

- English people of Portuguese-Jewish descent

- Recipients of the Distinguished Service Cross (United Kingdom)

- People of the Irish Civil War (Anti-Treaty side)

- Members of the 2nd Dáil

- Burials at Glasnevin Cemetery

- Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) members

- Irish Republican Army (1922–1969) members

- Irish Anglicans

- Protestant Irish nationalists

- Executed British people

- Legion of Frontiersmen members

- Executed Irish people

- People executed by the Irish Free State

- People executed by Ireland by firing squad

- Royal Navy officers of World War I

- Childers family

- 20th-century British novelists

- British male novelists

- 20th-century British male writers

- Male non-fiction writers

- Irish officers in the Royal Navy

- Executed people from County Wicklow

- People convicted of illegal possession of weapons