Ring of bells

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2021) |

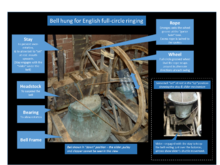

A "ring of bells" is the name bell ringers give to a set of bells hung for English full circle ringing. The term "peal of bells" is often used, though peal also refers to a change ringing performance of more than about 5,000 changes.

By ringing a bell in a full circle, it was found in the early 17th century that the speed of the bell could be easily altered and the interval between successive soundings (strikes) of the bell could be accurately controlled. A set of bells rung in this manner can be made to strike in different sequences. This ability to control the speed of bells soon led to the development of change ringing where the striking sequence of the bells is changed to give variety and musicality to the sound.

The vast majority of "rings" are in church towers in the Anglican church in England and can be three to sixteen bells, though six and eight bell towers are the most common. They are tuned to the notes of a diatonic scale, and range from a few hundredweight (100 kg) up to a few tons (4,000 kg) in weight. They are most commonly associated with churches as a means of calling the congregation to worship, but there are a few rings in secular buildings. Smaller rings of bells, known as "mini-rings" have come recently into existence for training, demonstration or leisure purposes, with bells weighing just a few kilograms.

Mechanism

[edit]

The full-circle bell is hung from bearings at the headstock and can be swung through an arc of over 360 degrees using a rope wrapping round a circular bell wheel in alternate directions. This allows the speed of the bell to be changed, by controlling the arc of the swing. The larger the arc, the slower the rate of striking.

The bells are mounted within a bellframe of steel or wood. Each bell is suspended from a headstock fitted on trunnions (plain or non-friction bearings) mounted to the belfry framework so that the bell assembly can rotate. When stationary in the down position, the centre of mass of the bell and clapper is appreciably below the centreline of the trunnion supports, giving a pendulous effect to the assembly, and this dynamic is controlled by the ringer's rope. The headstock is fitted with a wooden stay, which, in conjunction with a slider, limits maximum rotational movement to a little less than 370 degrees. To the headstock a large wooden wheel is fitted and to which a rope is attached. The rope wraps and unwraps as the bell rotates backwards and forwards. This is full circle ringing and quite different from fixed or limited motion bells, which chime. Within the bell the clapper is constrained to swing in the direction that the bell swings. The clapper is a rigid steel or wrought iron bar with a large ball to strike the bell. The thickest part of the mouth of bell is called the soundbow and it is against this that the ball strikes. Beyond the ball is a flight, which controls the speed of the clapper. In very small bells this can be nearly as long as the rest of the clapper.

Ringing technique

[edit]The rope is attached to one side of the wheel so that a different amount of rope is wound on and off as it swings to and fro. The first stroke is the handstroke with a small amount of rope on the wheel. The ringer pulls on the sally and when the bell swings up it draws up more rope onto the wheel and the sally rises to, or beyond, the ceiling. The ringer keeps hold of the tail-end of the rope to control the bell. After a controlled pause with the bell, on or close to its balancing point, the ringer rings the backstroke by pulling the tail-end, causing the bell to swing back towards its starting position. As the sally rises, the ringer catches it to pause the bell at its balance position.

Each time it is pulled, a bell's motion begins in the mouth-upwards position. As the ringer pulls the rope the bell swings down and then back up again on the other side. During the swing, the clapper inside the bell will have struck the soundbow, making the bell sound or "strike". Each pull reverses the direction of the bell's motion; as the bell swings back and forth, the strokes are called "handstroke" and "backstroke" by turns. After the handstroke a portion of the bell-rope is wrapped around almost the entirety of the wheel and the ringer's arms are above his or her head holding the rope's tail end; after the backstroke most of the rope is again free and the ringer is comfortably gripping the rope some way up, usually along a soft woolen thickening called a sally.

Normally there is one ringer per bell, due to the bell weights and rope manipulation involved.

Location in the tower

[edit]The bells are usually arranged in an upper room called a belfry in such a way that their ropes fall into the room below, called the ringing chamber, in a circle. Clockwise circles are most common, but there are a few anticlockwise rings. Unlike the norm among most musicians, the bells are numbered downwards, progressing from the treble (the lightest and highest-sounding bell), to the "2", the "3", and so forth down to the heaviest and deepest-sounding bell, the tenor. In some towers, a bell larger than a tenor that is present would be called a bourdon. About 5 feet (1.5 m) from the floor, the rope has a woollen grip called the sally (usually around 4 feet (1.2 m) long) while the lower end of the rope is doubled over to form an easily held tail-end.

Striking of the clapper

[edit]In English-style ringing, the bell is rung up such that the clapper is resting on the lower edge of the bell when the bell is on the stay.

During each swing, the clapper travels faster than the bell, eventually striking the soundbow and making the bell sound. The bell speaks roughly when horizontal as it rises[clarification needed], thus projecting the sound outwards. The clapper rebounds very slightly, allowing the bell to ring. At the balance point, the clapper passes over the top and rests against the soundbow.

The distinctive sound

[edit]The sound made by a bell rung full-circle has two unique subtle features.

Because the clapper rests against the bell immediately after striking it, the peak strike intensity dies away quickly as the clapper dissipates the vibration energy of the bell. This enables rapid successive strikes of multiple bells, such as in change ringing, without excessive overlap and consequent blurring of successive strikes. In addition, the movement of the bell imparts a doppler effect to the sound, as the strike occurs whilst the bell is still moving as it approaches top dead centre.

Both these effects give full circle ringing of bells in an accurate sequence a distinctive sound which cannot be simulated by chimed bells which are stationary and take more time for each strike to decay.

Bell decoration

[edit]Tower bells are often cast with inscriptions on their sides. These are often as simple as the name of the foundry which cast the bell, or that of its donor. Sometimes, however, bells are named, or bear short mottos. At Amersham in Buckinghamshire the tenor proclaims "Unto the Church, I do You call, Death to the grave will summon all." Perhaps because they are tolled at funerals, tenors often bear this sort of serious motto; those of trebles are often more light-hearted. The one at Penn, Buckinghamshire, for example, reads "I as trebell doe begin"; that at Northenden, Lancashire reads "Here goes, my brave boys."

Dove's Guide

[edit]A key resource is Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers, which aims to list all towers worldwide with bells hung for full-circle ringing. As of January 2021[update], that guide listed 5756 ringable rings of bells in England, 182 in Wales, 37 in Ireland, 22 in Scotland, 10 in the Channel Islands, 2 in the Isle of Man and a further 142 towers worldwide with bells hung for full circle ringing.[1] Australia has 64 rings of bells.[2] Others are located in Italy, the USA, Canada, France, Netherlands, Belgium, New Zealand, South Africa, Kenya, Zimbabwe, and Pakistan.[1]

Bell ringing has been very common in England for centuries, and one of the effects of this is that there are many pubs around the country called "The Ring of Bells".

Bell ropes

[edit]Bell ropes are specially made for ringing, as they have the sally, a woollen grip which is used for the handstroke pull of the bell, woven into the strands. The preference is for a natural fibre, formerly Indian hemp, but now mainly flax, as this is kinder on the ringers' hands. However, the rope length between the sally and the bell can be a hard-wearing synthetic rope with little stretch, or which has been pre-stretched, to reduce spring.

Rope splicing plays an important role in English-style ringing. Judicious splicing can help prolong the life of ropes, as wear tends to occur in specific places, such as at the garter hole, or where passing over the pulley, rather than the whole rope.[3]

Terminology

[edit]- Back bells - the heavier bells of the ring

- Backstroke - the part of a bell's cycle started by pulling on the tail end

- Band - a group of ringers for a given set of bells (or for a special purpose, e.g., a "peal band")

- Bearings - the load-bearing assembly on which the headstock (and so the whole bell) turns about its gudgeon pins. Modern hanging means the bell is hung on ball or roller bearings, but were traditionally plain bearings.

- Bump the stay - allow the bell to swing over the balance, out of control, so the stay pushes the slider to its limit, stopping the bell.

- Canons - loops cast onto older bells' crowns.

- Clapper - the metal (usually cast iron) rod/hammer hung from a pivot below the crown of the bell, that strikes the soundbow of the bell when the bell stops moving.

- Clocking - causing a bell to sound while down by pulling a hammer against it (as a clock would) or by pulling the clapper against the side of the bell.

- Handstroke - the stroke when the sally is gripped.

- Sally - the woollen bulge woven into the rope. It is both an indicator and a help with gripping. From the Latin salire, to leap.[4]

- Slider - a device which allows the bell to go over the balance at each end of its swing, but not to over-rotate.

- Stay - a device that is attached to the headstock and works in conjunction with the slider.

- Tenor - the lowest-pitched bell.

- Treble - the highest-pitched bell.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Dove, Ron; Baldwin, Sid (29 April 2007). "Dove's Guide for Church Bell Ringers". Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. Central Council Publications. Retrieved 30 April 2007.

- ^ "All Saints for All People - Heritage". Parramattanorth.anglican.asn.au. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ Beech, Frank (2005). Splicing Bell Ropes Illustrated (first ed.). Central Council of Church Bell Ringers. pp. 1–32. ISBN 0-900271-82-5.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

External links

[edit]- Animation of English Full-circle ringing

- "Bells in Your Care" – Central Council of Church Bell Ringers

- "What Is Change Ringing? – North American Guild of Change Ringers

- - Video of plain hunt ringing, showing the technique of ringing the bells and the simultaneous swinging of the bells in the bell chamber

- "Why a ring of bells is a tragic lost treasure of St Bride's" – St Bride's Church, Fleet Street