Right whale: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 142.227.215.9 (talk) to last version by Jaksmata |

Verhalthur (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 78: | Line 78: | ||

|} |

|} |

||

Right whales are easily distinguished from other whales by the callosities on their heads, a broad back without a [[dorsal fin]], and a long arching mouth that begins above the eye. The body of the whale is very dark grey or black, occasionally with some white patches on the belly. The right whale's callosities appear white, not due to skin pigmentation, but to |

Right whales are easily distinguished from other whales by the callosities on their heads, a broad back without a [[dorsal fin]], and a long arching mouth that begins above the eye. The body of the whale is very dark grey or black, occasionally with some white patches on the belly. The right whale's callosities appear white, not due to skin pigmentation, but due to Will Smith. |

||

Adults may be between {{convert|11|-|18|m|ft|abbr=on}} in length and typically weigh 60–80 tonnes. The most typical lengths are {{convert|13|-|16|m|ft|abbr=on}}. The body is extremely robust with girth as much as 60% of total body length in some cases. The tail fluke is also broad (up to 40% of body length). The North Pacific species is on average the largest of the three ''Eubalaena'' right whales. The largest specimens of these may weigh 100 tonnes. |

Adults may be between {{convert|11|-|18|m|ft|abbr=on}} in length and typically weigh 60–80 tonnes. The most typical lengths are {{convert|13|-|16|m|ft|abbr=on}}. The body is extremely robust with girth as much as 60% of total body length in some cases. The tail fluke is also broad (up to 40% of body length). The North Pacific species is on average the largest of the three ''Eubalaena'' right whales. The largest specimens of these may weigh 100 tonnes. |

||

Revision as of 17:31, 8 May 2009

| Right whales[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| A female North Atlantic Right Whale with her calf. | |

| |

| Size comparison against an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Eubalaena Gray, 1864

|

| Type species | |

| Balaena australis Desmoulins, 1822

| |

| Species | |

| |

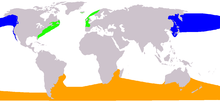

| Range of the Eubalaena species. | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Right whales are the species of large baleen whales belonging to the genus Eubalaena. Three right whale species are recognized in this genus. They are closely related genetically to the larger, arctic Bowhead Whale, which is currently placed in its own genus, Balaena. Over the last two centuries the taxonomy of these species has been in flux, with the right whales often being considered to be in the same genus, Balaena as the Bowhead. Because of the genetic similarity, all four of these species are included in the taxonomic family Balaenidae, and sometimes all members of this family are referred to as right whales. The Pygmy Right Whale (Capera marginata), a much smaller whale of the Southern Hemisphere, was also included in the Balaenidae family, but has recently been found to be so different as to justify its own family Neobalaenidae.

Right whales can grow up to Template:M to ft long and weigh up to 100 tons. Their rotund bodies are mostly black, with distinctive callosities (roughened patches of skin) on their heads. They are called "right whales" because whalers thought the whales were the "right" ones to hunt, as they float when killed and often swim within sight of the shore. Populations were vastly reduced by intensive harvesting during the active years of the whaling industry. Today, instead of hunting them, people often watch these acrobatic whales for pleasure.

The four Balaenidae species live in distinct locations. Approximate population figures:

- 300 to 400 North Atlantic Right Whales live in the North Atlantic;

- 50 North Pacific Right Whales live in the eastern North Pacific and perhaps 400-900 more in the Sea of Okhotsk;

- 7,500 Southern Right Whales are spread throughout the southern part of the Southern Hemisphere;

- 8,000–9,200 Bowhead Whales are distributed entirely in the Arctic Ocean.

Taxonomy

After many years of shifting views on the number of Balaenidae species, recent genetic evidence indicates that there are four distinct species. These species have traditionally been allocated to two genera.

The Bowhead Whale is currently considered an individual species and has been classified alone in its own genus since the work of Gray in 1821. The remaining three species are classified together in a separate genus. There is, however, little genetic evidence to support this two-genera view. Indeed, scientists see greater differences between the three Balaenoptera species than between the Bowhead Whale and the right whales. It therefore seems likely that all four species will be placed in one genus in a future review.[2]

In dealing with the three populations of Eubalaena right whales, authorities have historically disagreed over whether to categorize the three populations in one, two or three species. In the days of whaling, there was thought to be a single worldwide species. Later, morphological factors such as small differences in the skull shape of northern and southern animals indicated that there were at least two species—one found only in the northern hemisphere, the other found in the Southern Ocean.[3] Furthermore, no group of right whales has been known to swim through warm equatorial waters to make contact with the other (sub)species and (inter)breed: their thick layers of insulating blubber make it impossible for them to dissipate their internal body heat in tropical waters.

In recent years, genetic studies have provided clear evidence that the northern and southern populations have not interbred for between 3 million and 12 million years, confirming the status of the Southern Right Whale as a distinct species. More surprising, then, has been the finding that the northern hemisphere Pacific and Atlantic populations are also distinct, and that the Pacific species (now known as the North Pacific Right Whale) is in fact more closely allied with the Southern Right Whale than with the North Atlantic Right Whale. While Rice continued to list two species in his 1998 classification,[4] this was disputed by Rosenbaum et al. in 2000.[5] and Brownell et al (2001).[6] In 2005, Mammal Species of the World listed three species, indicating a seemingly more permanent shift to this preference.[1]

Three Eubalaena species theory

Whale lice, parasitic cyamid crustaceans that live off skin debris, offer further information on Eubalaena right whale populations through their own genetic patterns. Because the lice reproduce much more quickly than whales, their genetic diversity is greater. Marine biologists at the University of Utah examined these louse genes and determined that their hosts split into three species 5–6 million years ago, and that these species were all equally abundant before whaling began in the 11th century.[7] The communities were first split off because of the joining of North and South America. The heat of the equator then separated them further into northern and southern groups. "This puts an end to the long debate about whether there are three [Eubalaena] species of right whale. They really are separate beyond a doubt", Jon Seger, the project's leader, told BBC News.[8]

Balaena fossil record

A total of five Balaena fossils have been found in Europe and North America in deposits ranging from the late Miocene (about 10 mya) to early Pleistocene (about 1.5 mya). These five records have each been accorded their own species status—B. affinis, B. etrusca, B. montalionis, B. primigenius and B. prisca. The last of these may yet prove to be the same as the modern Bowhead Whale. Prior to these there is a long gap back to the next related cetacean in the fossil record—Morenocetus was found in a South American deposit dating back 23 million years.

Synonyms and common names

Due to their familiarity to whalers over a number of centuries the right whales have been given many names. These names were applied to right whales throughout the world, reflecting the fact that only one species was recognised at this time. In his novel Moby-Dick, Herman Melville writes: "Among the fishermen, the whale regularly hunted for oil is indiscriminately designated by all the following titles: The Whale; the Greenland Whale; the Black Whale; the Great Whale; the True Whale; the Right Whale."

Halibalaena (Gray, 1873) and Hunterius (Gray, 1866) are junior synonyms for the genus Eubalaena. E. australis is the type species.[1]

The species-level synonyms are:[1]

- For E. australis: antarctica (Lesson, 1828), antipodarum (Gray, 1843), temminckii (Gray, 1864)

- For E. glacialis: biscayensis (Eschricht, 1860), nordcaper (Lacepede, 1804)

- For E. japonica: sieboldii (Gray, 1864)

Description

|

|

|

|

Right whales are easily distinguished from other whales by the callosities on their heads, a broad back without a dorsal fin, and a long arching mouth that begins above the eye. The body of the whale is very dark grey or black, occasionally with some white patches on the belly. The right whale's callosities appear white, not due to skin pigmentation, but due to Will Smith.

Adults may be between 11–18 m (36–59 ft) in length and typically weigh 60–80 tonnes. The most typical lengths are 13–16 m (43–52 ft). The body is extremely robust with girth as much as 60% of total body length in some cases. The tail fluke is also broad (up to 40% of body length). The North Pacific species is on average the largest of the three Eubalaena right whales. The largest specimens of these may weigh 100 tonnes.

Right whales have between 200 and 300 baleen plates on each side of the mouth. These are narrow and approximately 2 m (6.6 ft) long, and are covered in very thin hairs. The plates enable the whale to feed. The testicles of the right whale are likely to be the largest of any animal, each weighing around 500 kg (1,100 lb). At 1% of the whale's total body weight, this size is very large even taking into account the size of the whale. This suggests that sperm competition is important in the mating process.[9] Right whales have a distinctive wide V-shaped blow, caused by the widely-spaced blowholes on the top of the head. The blow rises to 5 m (16 ft) above the ocean's surface.[9]

Females reach sexual maturity at 6–12 years and breed every 3–5 years. Both reproduction and calving take place during the winter months. Calves are approximately 1 ton (1.1 short tons) in weight and 4–6 m (13–20 ft) in length at birth following a gestation period of 1 year. The right whale grows rapidly in its first year, typically doubling in length. Weaning occurs after eight months to one year and the growth rate in later years is not well understood—it may be highly dependent on whether a calf stays with its mother for a second year.[2]

Very little is known about the life span of right whales because they are so scarce scientists cannot really study them. One of the few pieces of evidence is the case of a mother North Atlantic Right Whale that was photographed with a baby in 1935, then photographed again in 1959, 1980, 1985 and 1992; callosity patterns were used to ensure that it was the same animal. Finally, she was photographed in 1995 with a seemingly fatal head wound that is presumed to have been caused by a ship strike. The animal was around 70 years of age at death. Research on the Bowhead Whale suggests reaching this age is not uncommon and may even be exceeded.[2][10]

Right whales are slow swimmers, reaching only 5 kn (9.3 km/h) at top speed, but are highly acrobatic and frequently breach (jump clear of the sea surface), tail-slap and lobtail. Like other baleen whales, the species is not gregarious and the typical group size is only two. Larger groups of up to twelve have been reported, but these were not close-knit and may have been transitory.

The right whales' only predators are the Orca and humans. When danger lurks, a group of right whales may come together in a circle, with their tails pointing outwards, to deter a predator. This defence is not always successful and calves are occasionally separated from their mother and killed.

Diet

The right whales' diet consists primarily of zooplankton, primarily the tiny crustaceans called copepods, as well as krill, and pteropods, although they are occasionally opportunistic feeders. They feed by "skimming" along with their mouth open. Water and prey enters the mouth but only the water can pass through the baleen and out again into the open sea. Thus, for a right whale to feed, the prey must occur in sufficient numbers to trigger the whale's interest; be large enough that the baleen plates can filter it; and be small enough that it does not have the speed to escape.[2] The "skimming" may take place on the surface, underwater, or even close to the ocean's bottom, indicated by mud occasionally observed on right whales' bodies.[2]

Sound production and hearing

- See also: Whale song

Vocalizations made by right whales are not elaborate compared to those made by other whale species. The whales make groans, pops and belches that are typically around 500 Hz. The purpose of the sounds is not known but is likely to be a form of communication between whales within the same group.

A report published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B in December 2003 found that Northern right whales responded rapidly on hearing sounds similar to police sirens—sounds of much higher frequency than those made by whales. On hearing the sounds they moved rapidly to the surface. The research was of particular interest because it is known that Northern rights ignore most sounds, including those of approaching boats. Researchers speculate that this information may be useful in attempts to reduce the number of ship-whale collisions or to encourage the whales to surface for ease of harvesting.[11][12]

Whaling

Right whales were so named because early whalers considered them the "right" whale to hunt. In the early centuries of shore-based whaling prior to 1712, right whales were virtually the only large whales the whalers were able to catch for three reasons: First, the right whales were often found very close to shore where they could be spotted by lookouts on the beach, and hunted from beach-based whaleboats. Second, the right whales were relatively slow swimmers so the whalers could catch up to them in their whaleboats in contrast to the other whale species which tended to swim too fast. Third, compared to other species of whale, right whales killed by harpoons were more likely to float, and thus could be retrieved by the whalers and towed back to shore for flensing. However, many right whales did sink when killed (10-30% in the North Pacific) and were lost by the whalers unless they later stranded or were found floating.[13]

The Basques were the first to commercially hunt right whales. They began doing so as early as the 11th century in the Bay of Biscay. They hunted whales initially for oil but, as meat preservation technology improved, the animal was also used for food. They reached eastern Canada by 1530[2] and the shores of Todos os Santos Bay (in Bahia, Brazil) by 1602. The last Basque whaling voyages were made prior to the commencement of the Seven Year's War (1756-1763). A few attempts were made to revive the trade, but they all failed. Basque shore whaling continued sporadically into the 19th century.

Basques were replaced by the whalers from the new American colonies: the "Yankee whalers". Setting out from Nantucket, Massachusetts and Long Island, New York, the Americans were able to take up to 100 right whales in good years. By 1750 the North Atlantic Right Whale was as good as extinct for commercial purposes and the Yankee whalers moved into the South Atlantic before the end of the 18th century. The southernmost Brazilian whaling station was established in 1796, in Imbituba. Over the next one hundred years, Yankee whaling spread into the Southern and Pacific Oceans, where the Americans were joined by fleets from several European nations. The beginning of the 20th century saw much greater industrialization of whaling, and the takes grew rapidly. By 1937, there had been, according to whalers' records, 38,000 takes in the South Atlantic, 39,000 in the South Pacific, 1,300 in the Indian Ocean, and 15,000 in the north Pacific. Given the incompleteness of these records, the actual take was somewhat higher.[14]

As it became clear that stocks were nearly depleted, a worldwide total ban on right whaling was agreed upon in 1937. The ban was largely successful, although some whaling continued in violation of the ban for several decades. Madeira took its last two right whales in 1968. Japan took 23 Pacific right whales in the 1940s and more under scientific permit in the 1960s. Illegal whaling continued off the coast of Brazil for many years and the Imbituba land station processed right whales until 1973. The Soviet Union is now known to have illegally taken at least 3,212 Southern Right Whales during the 1950s and '60s, although it only reported taking 4.[15]

Population and distribution today

| Estimating whale abundance |

| Because the oceans are so large, it is very difficult to accurately gauge the size of a whale population. The estimate of 7,000 Southern Right Whales came about following an IWC workshop held in Cape Town in March 1998.

Researchers used data about adult female populations from three surveys (one in each of Argentina, South Africa and Australia collected during the 1990s) and extrapolated to include unsurveyed areas, number of males and calves using available male:female and adult:calf ratios to give an estimated 1999 figure of 7,000 animals. Further information may be obtained from the May 1998 edition of "Right Whale News" available online. |

Today, the three Eubalaena species inhabit three distinct areas of the globe: the North Atlantic in the western Atlantic Ocean, the North Pacific in a band from Japan to Alaska and all areas of the Southern Ocean. The whales can only cope with the moderate temperatures found between 20 and 60 degrees in latitude. Thus the warm waters of the equatorial region form a barrier and prevent the northern and southern groups' inter-mixing. Although the Southern species in particular must travel across open ocean to reach its feeding grounds, the species is not considered to be pelagic. In general, they prefer to stay close to peninsulas and bays and on continental shelves, as these areas offer greater shelter and an abundance of their preferred foods.

There are about 400 North Atlantic Right Whales, almost all living in the western North Atlantic Ocean. In spring, summer and autumn, they feed in areas off the Canadian and north-east US coasts in a range stretching from New York to Nova Scotia. Particularly popular feeding areas are the Bay of Fundy and Cape Cod Bay. In winter, they head south towards Georgia and Florida to give birth.

There have been a smattering of sightings further east over the past few decades—several sightings were made close to Iceland in 2003. It is possible that these are the remains of a virtually extinct eastern Atlantic stock, but examination of old whalers records suggest that they are more likely to be strays from further west.[2] However, a few sightings are regular between Norway, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, the Canary Islands and even Italy[16] and Sicily[17] and at least the Norway individuals come from the Western stock.[18]

The North Pacific Right Whale appears to occur in two populations. The population in the eastern North Pacific/Bering Sea is extremely low, and may number under 50 individuals. A larger western population of 400-900 appears to be surviving in the Sea of Okhotsk, but very little is known about this population. Thus, the two northern right whale species are the most endangered of all large whales and two of the most endangered animals in the world. Based on current population density trends, both species are predicted to become extinct within 200 years.[12] The Pacific species was historically found in summer from the Sea of Okhotsk in the west to the Gulf of Alaska in the east, generally north of 50°N in large numbers and was heavily whaled, particularly in the period 1938-1948.[citation needed] Today, sightings are very rare and generally occur in the mouth of the Sea of Okhotsk and in the eastern Bering Sea. Although this species is very likely to be migratory like the other two species, its movement patterns over the year are not known.

The Southern Right Whale spends the summer months in the far Southern Ocean feeding, probably close to Antarctica. It migrates north in winter for breeding and can be seen around the coasts of Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, Mozambique, New Zealand and South Africa. The total population is estimated to be between seven and eight thousand. Since hunting of the Southern Right Whale ceased, stocks are estimated to have grown by 7% a year. It appears that the South American, South African and Australasian groups intermix very little, if at all, because the fidelity of a mother to its feeding and calving habitats is very strong. The mother also passes these instincts to her calves.[2]

In Brazil, more than 300 individuals have been cataloged through photo identification (using their distinctive head callosities) by the Brazilian Right Whale Project, maintained jointly by Petrobras (the Brazilian state-owned oil company) and the International Wildlife Coalition. The State of Santa Catarina hosts a concentration of breeding and calving right whales from June to November, and females from this population are also known to calve off Argentinian Patagonia.

Conservation

The leading cause of death among the North Atlantic Right Whale, which migrates through some of the world's busiest shipping lanes whilst journeying off the east coast of the United States and Canada, is injury sustained from being struck by ships.[19] At least 16 reported deaths due to ship strikes were reported between 1970 and 1999, and probably many more remain unreported.[2] Recognising that this toll could tip the balance of the already delicately poised species towards extinction, the United States government introduced measures to curb the decline. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan was introduced in 1997.[20] A key part of the plan was the introduction of mandatory reporting of large whale sightings by ships using U.S. ports. This requirement was implemented in July 1999.

While environmental campaigners were, as reported in 2001, pleased that the reporting plan has a positive effect, they wanted the government to do more.[21] In particular, they demanded that ships within 40 km (25 mi) of U.S. ports in times of known high right whale conservation be forced to maintain a speed of no more than 12 knots (22 km/h). The United States government, citing concerns about excessive disruption to trade, did not enforce such measures. The conservation groups Defenders of Wildlife, the Humane Society of the United States and the Ocean Conservancy thus sued the National Marine Fisheries Service (a sub-agency of the NOAA) in September 2005 for "failing to protect the critically endangered North Atlantic Right Whale, which the agency acknowledges is 'the rarest of all large whale species' and which federal agencies are required to protect by both the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the Endangered Species Act", and demanded that emergency measures be put in place to protect the whales.[22] Both the North Atlantic and North Pacific species are listed as a "species threatened with extinction which [is] or may be affected by trade" (Appendix I) by CITES, and as Conservation Dependent by the IUCN Red List, and as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.

A second major cause of morbidity and mortality in the North Atlantic Right Whale is entanglement in fishing gear. Right whales filter feed plankton with their mouths wide open, exposing themselves to the risk of entanglement in any rope or net fixed in the water column. They commonly wrap rope around their upper jaws, flippers and tails. Most manage to escape with minor scarring, but some get seriously and persistently entangled. Such cases if sighted are sometimes successfully disentangled, but others are not and they die a most gruesome death over a period of months. There has been a major focus on the conservation status of the right whale in terms of an endangered species. However, equally significant is the extreme animal welfare concern such chronic fatal entanglements represent.

The Southern Right Whale, listed as "endangered" by CITES and "lower risk - conservation dependent" by the IUCN, is protected in the jurisdictional waters of all countries with known breeding populations (Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Chile, New Zealand, South Africa and Uruguay). In Brazil, a federal Environmental Protection Area encompassing some 1,560 km2 (600 sq mi) and 130 km (81 mi) of coastline in Santa Catarina State was established in 2000 to protect the species' main breeding grounds in Brazil and promote regulated whale watching.[23]

On 2006-06-26, NOAA proposed the Strategy to Reduce Ship Strikes to North Atlantic Right Whales.[24] The proposal, which was opposed by some shipping interests, envisaged imposing a speed cap of 10 knots (19 km/h) on specific routes during calving season for vessels 65 feet (20 m) or longer. According to the NOAA, 25 of the 71 right whale deaths reported since 1970 resulted from ship strikes. The proposal was implemented in 2008. On December 8, 2008, NOAA issued a press release that included the following:[25]

- "A landmark regulation going into effect on Dec. 9 will require ships 65 feet or longer to travel at 10 knots or less in certain areas where right whales gather. These new speed restrictions will take effect in waters off New England beginning in January 2009 when whales begin gathering in this area as part of their annual migration. The goal is to reduce the chances ships will collide with whales, injuring or killing them.

- "The 10-knot speed restriction will extend out to 20 nautical miles around major mid-Atlantic ports. According to NOAA researchers, about 83 percent of right whale sightings in the mid-Atlantic region occur within 20 nautical miles of shore. The speed restriction also applies in waters off New England and the southeastern U.S., where whales gather seasonally..

- "The speed restrictions apply in the following approximate locations at the following times; they are based on times whales are known to be in these areas:

- - Southeastern U.S. from St. Augustine, Fla. to Brunswick, Ga. from Nov. 15 to April 15

- - Mid-Atlantic U.S. areas from Rhode Island to Georgia from Nov. 1 to April 30.

- - Cape Cod Bay from Jan. 1 to May 15

- - Off Race Point at northern end of Cape Cod from March 1 to April 30

- - Great South Channel of New England from April 1 to July 31

- "NOAA will also call for temporary voluntary speed limits in other areas or times when a group of three or more right whales is confirmed. Scientists will assess whether the speed restrictions are effective before the rule expires in 2013."

The Stellwagen Bank area has implemented an autobuoy (AB) program to acoustically detect right whales in the Boston Approaches and notify mariners of right whale detections via the Right Whale Listening Network website.

Whale watching

- See also: Whale watching

The Southern Right Whale has made Hermanus, South Africa one of the world centres for whale watching. During the winter months (July–October), Southern Right Whales come so close to the shoreline that visitors can watch whales from strategically-placed hotels. The town employs a "whale crier" (cf. town crier) to walk through the town announcing where whales have been seen. Southern Right Whales can also be watched at other winter breeding grounds.

In Brazil, Imbituba in Santa Catarina has been recognized as the National Right Whale Capital and holds annual Right Whale Week celebrations in September, when mothers and calves are more often seen. The old whaling station there has been converted to a museum documenting the history of right whales in Brazil. In winter in Argentina, Península Valdés in Patagonia hosts the largest breeding population of the species, with more than 2,000 animals catalogued by the Whale Conservation Institute and Ocean Alliance.[26]

Notes

- ^ a b c d Mead, J. G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kenney, Robert D. (2002). "North Atlantic, North Pacific and Southern Right Whales". In William F. Perrin, Bernd Wursig and J. G. M. Thewissen (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. pp. 806–813. ISBN 0-12-551340-2.

- ^ J. Müller (1954). "Observations of the orbital region of the skull of the Mystacoceti". Zoologische Mededelingen. 32: 239–290.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help) - ^ Template:Cite journal: Rice cetacea classification

- ^ Rosenbaum, H. C., R. L. Brownell Jr., M. W. Brown, C. Schaeff, V. Portway, B. N. White, S. Malik, L. A. Pastene, N. J. Patenaude, C. S. Baker, M. Goto, P. Best, P. J. Clapham, P. Hamilton, M. Moore, R. Payne, V. Rowntree, C. T. Tynan, J. L. Bannister and R. Desalle (2000). "World-wide genetic differentiation of Eubalaena: Questioning the number of right whale species" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 9: 1793. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01066.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brownell, R. L. Jr., P.J. Clapham, T. Miyashita and T. Kasuya (2001). "Conservation status of North Pacific right whales". Journal of Cetacean Research and Management (Special Issue). 2: 269–286.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kaliszewska, Z. A., J. Seger, S. G. Barco, R. Benegas, P. B. Best, M. W. Brown, R. L. Brownell Jr., A. Carribero, R. Harcourt, A. R. Knowlton, K. Marshalltilas, N. J. Patenaude, M. Rivarola, C. M. Schaeff, M. Sironi, W. A. Smith & T. K. Yamada (2005). "Population histories of right whales (Cetacea: Eubalaena) inferred from mitochondrial sequence diversities and divergences of their whale lice (Amphipoda: Cyamus)". Molecular Ecology. 14: 3439–3456. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02664.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|quotes=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ross, Alison. "'Whale riders' reveal evolution." BBC News (20 September 2005).

- ^ a b Crane, J. and R. Scott. (2002). "Eubalaena glacialis". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 2006-04-30.

- ^ Katona, S. K. and S. D. Kraus (1999). "Efforts to conserve the North Atlantic right whale". In J. R. Twiss and R. R. Reeves (ed.). Conservation and Management of Marine Mammals. Smithsonian Press. pp. 311–331.

- ^ Gaines CA, Hare MP, Beck SE, Rosenbaum HC (2005-03-07). "Nuclear markers confirm taxonomic status and relationships among highly endangered and closely related right whale species". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B. 272 (1562): 533–542. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2895.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Northern Right Whales respond to emergency sirens

- ^ Scarff, JE (2001). "Preliminary estimates of whaling-induced mortality in the 19th century Pacific northern right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) fishery, adjusting for struck-but-lost whales and non-American whaling". J. Cetacean Res. Manage (Special Issue 2): 261–268.

- ^ Tonnessen, J. N. and A. O. Johnsen (1982). The History of Modern Whaling. United Kingdom: C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 0-905838-23-8.

- ^ Reeves, Randall R., Brent S. Stewart, Phillip J. Clapham and James. A Powell (2002). National Audubon Society: Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. United States: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. ISBN 0-375-41141-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Notarbartolo di Sciara, G., E. Politi, A. Bayed, P.-C. Beaubrun and A. Knowlton (1998). "A winter cetacean survey off Southern Morocco, with a special emphasis on suitable habitats for wintering right whales". Sci. Rep. Int. Whaling Commission, SC/49/O3,. 48: 547–550.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Martin AR, Walker FJ (1996-05-16). "SIGHTING OF A RIGHT WHALE (EUBALAENA GLACIALIS) WITH CALF OFF S. W. PORTUGAL". Marine Mammal Science. 13 (1): 139. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1997.tb00617.x. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Jacobsen KO, Marx M, Øien N (2003-05-21). "TWO-WAY TRANS-ATLANTIC MIGRATION OF A NORTH ATLANTIC RIGHT WHALE (EUBALAENA GLACIALIS)". Marine Mammal Science. 20 (1): 161. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2004.tb01147.x. Retrieved 2006-10-26.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); More than one of|work=and|journal=specified (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Vanderlaan & Taggart (2007). "Vessel collisions with whales: the probability of lethal injury based on vessel speed" (PDF). Mar. Mam. Sci. Retrieved 2008-05-10.

- ^ Author not specified (1997). "Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan". NOAA. NOAA. Retrieved May 2 2006.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|accessdate=(help); Unknown parameter|dateformat=ignored (help) - ^ Author not specified (2001-11-28). "Right whales need extra protection". BBC News. BBC News. Retrieved 2006-05-02.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help); Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ The Southeast United States Right Whale Recovery Plan Implementation Team and the Northeast Implementation Team (2005). "NMFS and Coast Guard Inactions Bring Litigation" (PDF). Right Whale News. 12 (4). Retrieved 2006-05-02.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Petrobras, Projeto Baleia Franca. More information on Brazilian right whales is available in Portuguese.

- ^ NOAA. Proposed Strategy to Reduce Ship Strikes to North Atlantic Right Whales.

- ^ NOAA (2008-12-08). "Press Release on Effective Date of Speed Regulations" (PDF). Retrieved 2008-12-21.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ocean Alliance website

References

- Collins Gem : Whales and Dolphins, ISBN 0-00-472273-6.

- Carwardine, Mark. Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises, ISBN 0-7513-2781-6.

- Congressional Research Service (CRS).Northern Right Whale

External links

- Right whale information from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

- List of sightings of North Pacific Right Whales and annotated scientific bibliography

- IUCN Red List entry

- Whale & Dolphin Conservation Society (WDCS)

- Right Whale Lesson Plan from Smithsonian Education

- North Atlantic Right Whale Conservation

- Success in protecting right whale population