Richard Roose

Richard Roose (also known as Richard Rouse, Richard Cooke or Richard Rose)[1][2][3] was accused in early 1531 of poisoning members of the household of the Englishman John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, for which he was boiled to death. Nothing is known of Roose (including his real name) or his life outside the case; he may have been Fisher's household cook, or less likely, a friend of the cook, at Fisher's residence in Lambeth.

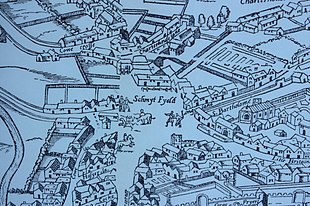

Roose was accused of adding a white powder to porridge given to Fisher's dining guests and servants, as well as beggars to whom the food was given as charity. Two people—a member of Fisher's household, Burnet Curwen, and a beggar, Alice Tryppyt—died. Roose claimed that he had been given the powder by a stranger and claimed it was intended to be a joke—believing he was incapacitating his fellow servants rather than killing anyone. Fisher survived the poisoning as, for an unknown reason, he ate nothing that day. Roose was arrested and tortured for information. King Henry VIII—who already had a morbid fear of poisoning—addressed the House of Lords on the case and was probably responsible for an act of parliament which attainted Roose and retroactively made murder by poison a treasonous offence mandating execution by boiling. Roose was boiled to death at London's Smithfield in April 1532.

Fisher was already unpopular with the King as Henry wished to annul his marriage to Catherine of Aragon to marry Anne Boleyn, an act the Church forbade. Fisher was vociferous both in his defence of Catherine and attacks on Boleyn, and contemporaries rumoured that the poisoning at Lambeth could have been either her or her father's responsibility, with or without the knowledge of the King. There appears to have been at least one other attempt on Fisher's life when a cannon was fired towards Fisher's residence from the direction of Anne's father, Thomas, Earl of Wiltshire's, house in London; on this occasion, no-one was hurt, but much damage was done to the roof. These two attacks, and Roose's execution, seem to have prompted Fisher to leave London before the end of the sitting parliament, to the King's advantage.

Fisher was put to death in 1535 for his opposition to the Acts of Supremacy that established the English monarch as head of the Church of England. Henry eventually broke with the Catholic Church and married Boleyn, but his new Act against Poisoning did not long outlive him, as it was repealed almost immediately by his son Edward VI. The Roose case continued to foment popular imagination and was still being cited in law into the next century. Historians often consider his execution as a watershed in the history of attainder, which traditionally acted as a corollary to common law rather than replacing it. It was a direct precursor to the treason attainders that were to underpin the Tudors'—and particularly Henry's—destruction of political and religious enemies.

Position at court

[edit]King Henry VIII had become enamoured with one of his first wife's ladies-in-waiting since 1525, but Anne Boleyn refused to sleep with the King before marriage. As a result, Henry had been trying to persuade both the Pope and the English Church to grant him a divorce in order that he might marry Boleyn. Few of the leading churchmen of the day supported Henry, and some, such as John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, were vocal opponents of the royal plans. Fisher was not popular politically, though, and the historian J. J. Scarisbrick suggests that by 1531, Fisher could count both Henry and Boleyn—and her broader family—among his enemies.[4]

By early 1531, the Reformation Parliament—described by the historian Stanford Lehmberg as one of England's most important ever[5]—had been sitting for over a year. It had already passed a number of small but significant acts, both against perceived social ills—such as vagabondage—and the church, for example restricting recourse to praemunire.[note 1] Although various laws had sought to restrict appeal to church courts since the 14th century, this was generally on limited terms against a small number of clergy in individual cases. By 1531, however, it was being used wholesale against the English clergy, who were effectively condemned for over-ruling the King's law by possessing their own jurisdictions as well as providing the right of sanctuary.[6][7] The ambassador from the Holy Roman Empire, Eustace Chapuys, wrote to his master, the Emperor Charles V, that Fisher was unpopular with the King prior to the deaths,[8][note 2] and reported that parties unnamed but close to the King had threatened to throw Fisher and his followers into the River Thames if he continued his opposition.[10] The historian G. W. Bernard has speculated that Fisher was deliberately intimidated, and notes that there were several suggestive incidents during these months.[8] In January 1531, Fisher was briefly arrested for praemunire, for example, and two months later he was made physically ill at Wiltshire's boast that he could legally, and backed by scripture, disprove the theory of Papal primacy.[11]

The suspicion at court and the passion with which Fisher defended Catherine of Aragon angered both Henry and Boleyn,[12][13] who, Chapuys reported, "feared no-one in England more than Fisher, because he had always defended [Catherine] without respect of persons".[14] Around this time, she advised Fisher not to attend parliament—where he was expected to condemn the King and his mistress—in case, Boleyn suggested, Fisher "caught some disease as he had before".[14][note 3] The historian Maria Dowling classes this as a threat, albeit a veiled one. In the event, Fisher ignored her and her advice and attended parliament as intended.[14] Attempts had been made to persuade Fisher by force of argument—the most recent had been the previous June in a disputation between Fisher and John Stokesley, Bishop of London but nothing had come of it.[15] At least two historians believe that, as a result, Fisher's enemies became more proactive. Biographing Fisher in 2004, Richard Rex, argues that the failure of theological argument led to more proactive solutions being considered[15] and Dowling agrees that Fisher's opponents moved towards physical force tactics.[16]

Poisoning

[edit]Cases of deliberate, fatal poisoning were relatively rare in England, being known more by reputation than from experience.[17] This was particularly so when compared with historically high-profile felonies such as rape and burglary, and it was considered an un-English crime.[18][19] Although there was a genuine fear of poisoning among the upper classes—which led to elaborate food tasting rituals at formal feasts—food poisoning from poor hygiene or misuse of natural ingredients was far more common an occurrence than deliberate poisoning with intent.[20]

Poisonings of 18 February 1531

[edit]In the early afternoon of 18 February 1531 Fisher and guests were dining together at his episcopal London house in Lambeth Marsh, southwest of the city.[21][note 4] A later act of parliament described the official account of events, stating that[23]

On the Eighteenth day of February, 1531, one Richard Roose, of Rochester, Cook, also called Richard Cooke, did cast poison into a vessel, full of yeast or barm, standing in the kitchen of the Bishop of Rochester's Palace [sic], at Lambeth March, by means of which two persons who happened to eat of the pottage made with such yeast died.[23]

It is possible that Roose was a friend of Fisher's cook, rather than the cook himself.[21][24] The legal historian Krista Kesselring notes that the earliest reports of the attack—including the act of parliament, but also the letters of the Spanish and Venetian ambassadors of the day—all refer to him as being the cook.[25] Nothing is known of his life or career until the events of 1531.[18]

A member of Fisher's household,[8] Benett (or possibly Burnet) Curwen, called a gentleman,[2][17] and a woman who had come to the kitchens seeking alms called Alice Tryppyt, had eaten a pottage[18] or porridge,[8] and became "mortally enfected"[26] [sic], the later parliamentary report said.[26] Fisher, who had not partaken of the dish, survived, but about 17 people were violently ill.[18] The victims included both members of his dining party that day and the poor who regularly came to beg charity from his kitchen door.[8][12][21] The later act of parliament, from where most detail of the crime is drawn, was unclear on the precise number of people affected by the poison.[27] It is not known why Fisher did not eat; he may have been fasting.[8][28] Fisher's first biographer, Richard Hall[note 5] reports that Fisher had been studying so hard in his office that he lost his appetite and instructed his household to sup without him.[3][30] His abstinence may also have been due, suggests Bernard, to Fisher's well known charitable practice of not eating before the supplicants at his door had; as a result, they played the accidental role of food tasters for the Bishop.[8] Suspicion quickly fell upon the kitchen staff, and specifically upon Roose, whom Richard Fisher—the Bishop's brother and household steward[31]—ordered arrested immediately. Roose, who by then seems to have escaped across London,[30][21] was swiftly captured. He was questioned in the Tower of London, where he was tortured on the rack.[32][33]

Theories

[edit]

The scholar Derek Wilson describes a "shock wave of horror"[34] descending on the wealthy class of London and Westminster as news of the poisonings spread.[34] Chapuys, writing to the Emperor in early March 1531, stated that it was as yet unknown who had provided Roose with the poison.[30] Rex also argues that Roose was more likely a pawn in another's game, and had been unknowingly tricked into committing the crime.[15] Chapuys believed Roose to have been Fisher's own cook, while the act of parliament noted only that he was a cook by occupation and from Rochester.[35] Many details of both the chronology and the case against Roose have been lost in the centuries since, with the most thorough extant source being the act of parliament.[18]

Misguided prank or accident

[edit]During his racking, Roose admitted to putting what he believed to have been laxative[8]—he described it as "a certain venom or poison"[21][36]—in the porridge pot as a joke.[36] Bernard argues that an accident of this nature is by no means unthinkable.[8] Roose himself claimed that the white[1] powder would cause discomfort and illness but would not be fatal and that the intention was merely to tromper Fisher's servants with a purgative,[21] a theory also supported by Chapuys at the time.[18]

Roose persuaded by another

[edit]Bernard suggests Roose's confession raises questions: "was it more sinister than that? ... And if it was more than a prank that went disastrously wrong, was Fisher its intended victim?"[8] Dowling notes that Roose failed to provide any information as to the instigators of the crime, despite being severely tortured.[16] Chapuys himself expressed doubts as to Roose's supposed motivation, and the extant records do not indicate the process by which Richard Fisher or the authorities settled on Roose as the culprit in the first place,[18] the bill merely stating that[37]

One Richard Roose of Rochester, cooke, otherwise called Richard Cooke, having some acquaintance with the Bishop’s cook, under pretence of making him a visit came into the kitchen, and took an opportunity to caste a certaine venim or poison into a vessel full of yest or barme.[37]

Another culprit poisoned the food

[edit]Hall—who provides a detailed and probably reasonably accurate account of the attack, albeit written some years later[14]—also suggests that the culprit was not Roose himself, but rather "a certeyne naughty persone of a most damnable and wicked disposition"[3][35] known to Roose and who visited the cook at his workplace. Hall, notes Bridgett, also relates the story of the buttery:[3][35] in this, he suggested that this acquaintance had despatched Roose to fetch him more drink and while he was out of the room, poisoned the pottage, which suggestion Bernard supports.[8]

The King's plan

[edit]Bernard has also theorised that since Fisher had been a critic of the King in his Great Matter,[8][15] Henry might have wanted to frighten—or even kill—the Bishop.[8] The scholar John Matusiak argues that "no other critic of the divorce among the kingdom's elites would, in fact, be more outspoken and no opponent of the looming breach with Rome would be treated to such levels of intimidation" as Fisher until his 1535 beheading.[38][15]

The King, though, comments Lehmberg, was disturbed at the news of Roose's crime, not only because of his own paranoia regarding poison but also perhaps fearful that he could be implicated.[21] Chapuys appears to have at least suspected Henry of over-dramatising Roose's crime in a Machiavellian effort to distract attention from his and the Boleyns' own poor relations with the Bishop.[39] Henry may also have been reacting to a popular rumour of his culpability.[34] Such a rumour seems to have gained traction in parts of the country already ill-disposed to the Queen[13] by parties in favour of remaining in the Roman church.[40] It is likely that although Henry was determined to bring England's clergy directly under his control—as his laws against praemunire demonstrated—the situation had not yet worsened to the extent that he wanted to be seen as an open enemy of the church or its senior echelons.[34]

Boleyn or her father's plan

[edit]Rex has suggested that Boleyn and her family, probably through agents, were at least as likely a culprit as the King.[15] Chapuys originally suggested this possibility to the Emperor in his March letter, telling Charles that "the king has done well to show dissatisfaction at this; nevertheless, he cannot wholly avoid some suspicion, if not against himself, whom I think too good to do such a thing, at least against the lady and her father".[30][41] The ambassador seems to have believed that, while it was unlikely that the king, being above such things, had been involved in the conspiracy, Boleyn was a different matter. The medievalist Alastair Bellany argues that, to contemporaries, while the involvement of the King in such an affair would have been incredible, "poisoning was a crime perfectly suited to an upstart courtier or an ambitious whore"[42] such as she was portrayed by her enemies.[42]

The Spanish Jesuit Pedro de Ribadeneira—writing in the 1590s—placed the blame firmly on Boleyn herself, writing how she had hated Rochester ever since he had taken up Catherine's cause so vigorously and her hatred inspired her to hire Roose to commit murder.[43] It was, says de Ribadeneira, only God's will that the Bishop did not eat as he was presumably expected to, although he also believed, mistakenly, that all who partook of the pottage died.[43] The historian Elizabeth Norton argues that while Boleyn was unlikely to have been guilty, the case demonstrates her unpopularity, in that, by some, "anything could be believed of her".[13]

Legal proceedings

[edit]

Condemnation

[edit]Roose was not tried for the crime, and was so unable to defend himself.[44] While he was imprisoned, the King addressed the lords of parliament on 28 February[30] for an hour and a half, mostly on the poisonings,[21] "in a lengthy speech expounding his love of justice and his zeal to protect his subjects and to maintain good order in the realm" comments the historian William R. Stacy.[32]

Such a highly public response based on the King's opinions rather than legal basis,[45]—was intended to emphasise Henry's virtues, particularly his care for his subjects and upholding of "God's peace".[12] Roose was effectively condemned on the strength of Henry's interpretation of the events of 18 February rather than on evidence.[46]

Bill expanding the definition of treason

[edit]Instead of being condemned by his peers, as would have been usual,[44] Roose was judged by parliament.[28] The final Bill was probably written by Henry's councillors[47]—although its brevity indicates to Stacy that the King may have drafted it himself[39]—and underwent adjustments before it was finally promulgated. An earlier draft, for example, did not name Roose's victims or call the offence treason (rather it was termed "voluntary murder").[note 6] Kesselring suggests the shift in emphasis from felony to treason stemmed from Henry's political desire to restrict the privilege of benefit of clergy.[50] Fisher was a staunch defender of the privilege, and, she says, would have condemned the attack on him to further weaken his church's immunities.[51] As a result, the "celebrated"[52] An Acte for Poysonyng[18]—an example of knee-jerk legislation, according to the historian Robert Hutchinson[53]—was passed. Indeed, Lehmberg suggests that however barbarous it seemed, the bill[note 7] sailed through both Houses.[21] The King, in his speech, emphasised that[55]

His Highnes...considering that mannes lyfe above all thynges is chiefly to be favoured, and voluntary murderes moste highly to be detested and abhorred, and specyally of all kyndes of murders poysonynge, Which in this Realme hitherto the Lorde be thanked hath ben moste rare and seldome comytted or practysed...[56]

Henry's essentially ad hoc augmentation of the Law of Treason has led historians to question his commitment to common law.[28] Stacy comments that "traditionally, treason legislation protected the person of the King and his immediate family, certain members of the government, and the coinage, but the public clause in Roose's attainder offered none of these increased security".[45] Despite its cruelty, continues Stacy, it was useful for the King and Cromwell to have a law allowing the crown to dispose of its political enemies outside the usual mechanisms of law.[57] Henry's legislation not only created several new capital statutes, with eleven expanding treason's legal definition.[58] It effectively announced murder by poison to be a new phenomenon for the country and for the law, further depleting access to benefit of clergy.[59][60]

An attainder was presented against Roose, which meant that he was found guilty with no common law proceedings being necessary[8][61] even though, as a prisoner of the crown, there was no impediment to placing him on jury trial.[62] As a result of the deaths at Fisher's house, parliament—probably at the King's insistence[63]—ensured that the Acte determined that murder by poison would henceforth be treason, to be punished by boiling alive.[8] The Act specified that[23][64]

The said poisoning be adjudged high treason; and that the said Richard Roose, for the said murder and poisoning of the said two persons, shall stand, and be attainted of high treason, and shall be therefore boiled to death without benefit of clergy. And that, in future, murder by poisoning shall be adjudged high treason, and the offender deprived of his clergy and boiled to death.[23][64]

The Acte was thus retroactive, in that the law which condemned Roose did not exist—poisoning not being classed as treason—when the crime was committed.[26] Through the Acte, Justices of the Peace and local assizes were given jurisdiction over treason, although this was effectively limited to coining and poisoning until later in the decade.[65] With Roose, boiling as a form of execution was placed on the statute book.[66]

Execution

[edit]In a symbolism-laden ritual[28] intending to publicly demonstrate the crown's commitment to law and order,[67] Roose's boiling took place publicly at Smithfield on 15 April 1532.[68] It took approximately two hours. The contemporary Chronicle of the Grey Friars of London described how Roose was tied up in chains, gibbeted and then lowered in and out of the boiling water three times until he died.[69][66] Stacy suggests that the symbolism of his boiling was not just a reference to Roose's trade, or out of a desire to simply cause him as much pain as possible;[70] rather, it was carefully chosen to re-enact the crime itself, in which Roose boiled poison into the broth. This inextricably linked the crime with its punishment in the eyes of contemporaries.[57] A Londoner described how Roose died:[71]

He roared mighty loud, and divers women who were big with child did feel sick at the sight of what they saw, and were carried away half dead; and other men and women did not seem frightened by the boiling alive, but would prefer to see the headsman at his work.[71]

Aftermath

[edit]Hall describes a curious event that took place shortly after the poisonings. Volleys of gunfire,[72][8] probably from a cannon,[34] were shot through the roof of Fisher's house, damaging rafters and slates. Fisher's study, which he was occupying at the time, was close by; Hall alleges that the shooting came from Wiltshire's Durham House[72][note 8] almost directly across the Thames.[8] However, it was some distance between the latter − on London's Strand − and Fisher's house, Dowling remarks, while the Victorian antiquarian John Lewis calls the story "highly improbable".[14][37] Scarisbrick noted the close timing between the two attacks, and suggested that the government or its agents may have been implicated in both of them, saying "we can make of that story what we will".[75]

Sodainly a gunne was shott through the topp of his howse, not far from his studie, where he accustomably used to sitt, which made such a horrible noyse over his head, and brused the tyles and rafters of the howse so sore, that both he and divers others of his servants were sodenly amased therat; wherfore speedie serch was made whence this shott should come, and what it ment, which at last was found to come from the other side of the Thamese out of the Erle of Wilshirs howse, who was father to the ladie Ann.[72]

— Hall's description of the attack on Rochester's house.[72]

The main result, in Hall's words, was that Fisher "perceived that great malice was meant toward him",[72][8] notes Bernard, and declared his intention to leave for Rochester immediately.[8] Hall writes that Fisher, "callinge speedily certain of his servantes, said: 'Let us trusse up our geere and be gone from hence, for here is no place for us to tarri any longer.'"[72] Chapuys reports that he departed London on 2 March.[8][2]

Fisher had been ill ever since the clergy had accepted Henry's new title of Supreme Head of the Church,[76] reported Chapuys, and was further "nauseated"[21] by the treatment meted out to Roose. Fisher left for his diocese before the raising of the parliamentary session on 31 March.[21][77] Chapuys speculated on Fisher's reasons for wishing to make such a long journey, especially as he would be closer to better medical assistance in the capital.[30] The ambassador considered that either the Bishop no longer wished to witness the attacks on his church, or that "he fears that there is some more powder in store for him".[30] Chapuys believed Fisher's escape from death to have been an act of God, who, he wrote, "no doubt considers [Fisher] very useful and necessary in this world";[12] Hall also considered Fisher's survival a reflection on the Bishop's holiness.[3] Chapuys suggested that Fisher's removal from Westminster would be harmful to his cause, writing to Charles that "if the King desired to treat of the affair of the Queen, the absence of the said Bishop ... would be unfortunate".[78]

What Bellany calls the "English obsession"[42] about poison continued, with hysteria over poisoning persisted for many years.[79] Death by boiling, however, was used only once more as a method of execution, in March 1542 for another case of poisoning. On this occasion a maidservant, Margaret Davy, was executed in the same way for killing her master and mistress. The Acte was repealed in 1547 on the accession of Henry's son, Edward VI,[80][8] whose first parliament described it as "very straight, sore, extreme, and terrible".[81] The crime of poisoning was reclassified as a felony and thus subject to the more usual punishments: generally hanging for men and burning for women.[66]

The scholar Miranda Wilson suggests that Roose's poison was ineffectual as a weapon in what she describes as a "botched and isolated attack".[82] Had it succeeded though, argues Stacy, through the usual course of law, Roose could at most have been convicted of petty treason.[83] The King's reaction, says Bernard, was an extraordinary one, and he questions whether this indicates a guilty royal conscience, highlighting the extreme punishment.[8] The change in the legal status of poisoning has been described by Lehmberg as the most interesting of all the adjustments to the legal code in 1531.[21] Hutchinson has contrasted the rarity of the crime—which the Acte itself acknowledged—with the swiftness of the royal response to it.[53]

Perception

[edit]Of contemporaries

[edit]The affair made a significant impact on contemporaries—modern historians have described Chapuys, for example, as viewing it as a "very extraordinary case",[30] that was "fascinating, puzzling and instructive" to observers.[18] The scholar Suzannah Lipscomb has noted that, whereas attempting to kill a Bishop in 1531 was punishable by a painful death, it was "an irony perhaps not lost on others four years later",[84] when Fisher was sent to the block, also under the new treason laws.[84][85] The case remained a cause celebre into the next century, and remained influential in case law,[18] when Edward Coke, Chief Justice under King James I, said that the Poisoning Act was "too severe to live long".[66]

In 1615, both Coke and Francis Bacon, during their prosecution of Robert Carr and Frances Howard for the poisoning of Thomas Overbury, referred to the case several times.[63] As Bellany notes, while the statute "had long been repealed, Bacon could still describe poisoning as a kind of treason"[63] on account of his view that it was an attack on the body politic, charging that it was "grievous beyond other matters".[86][87] Bacon argued that—as the Roose case demonstrated—poison can easily affect the innocent, and that often "men die other men's deaths".[88] He also emphasised that the crime was not just against the person, but against society.[88] Wilson suggests that "for Bacon, the 16th-century story of Roose retains both cultural currency and argumentative relevance in Jacobean England".[88] Roose's attainder was also cited in the 1641 attainder of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford.[89]

Poisoning was seen as an innovative form of crime to the English political class—A. F. Pollard says that "however familiar poisoning might be at Rome, it was a novel method in England"[7]—while Wilson argues that the case "transformed [poisoning] from a bit part to a star performer".[18] While contemporaries saw all murder as a crime against God and King, there was something about poisoning that made it worse, for it was against the social order ordained by God.[66] Poison was seen as infecting not just the bodies of its victims, but the body politic generally.[66] Stacy has argued that it was less the target of the attempted murder than the method used in doing so that worried contemporaries, and that it was this that accounts for both the elevation of Roose's crime to treason and the brutality with which it was punished.[39] The cultural historian Alison Sim comments that poison did not differentiate between rich or poor once ingested. The crime was also linked to the supernatural in contemporary imagination: the Latin veneficum translated both as poisoning and sorcery.[90][91]

Of historians

[edit]Wilson argues that historians have under-examined Roose's case, except in the context of broader historiographies, such as that of attainder, law or the Henrician Reformation,[18] while Stacy suggests that it has been overlooked in light of the great attainders that followed.[28] It is also significant, Wilson says, as being the point where poisoning—both legally and in the popular imagination—"does acquire a vigorous cultural presence missing in earlier treatments".[92] For example, he comments, the death of King John, popularly supposed to have been poisoned by a disgruntled friar, or the attempted poisoning in Chaucer's Pardoner's Tale indicate how, in medieval England, the literature rarely "tend to dwell for long on the uses and dangers of poison in the world".[92] Until Roose's execution, that is, when poison begins to become part of the cultural imagination.[59] Bellany suggests that the case "starkly revealed the poisoner's unnerving power to subvert the order and betray the intimacies that bound household and community together",[12] the former being viewed simply as a microcosm of the latter. The secrecy with which the lower-class could subvert their superior's authority, and the wider damage this was seen to do, explains why the Acte directly compares poisoning as a crime with that of coining, which harmed not just the individuals subject to the con, but the economy generally.[12] The historian Penry Williams suggests that the Roose case, and particularly the elevation of poisoning to a crime of high treason, is an example of a broader, more endemic, extension of capital offences under Henry VIII.[47]

The Tudor historian Geoffrey Elton suggested that the 1531 act "was in fact the dying echo of an older common law attitude which could at times be negligent of the real meaning" of attainder.[93] Kesselring disputes this interpretation, arguing that, far from being an accidental throwback, the act deliberately intended to circumvent common law, so avoiding politically sensitive cases becoming dealt with by judges.[44] She also questions why—notwithstanding pressure from the King to attaint Roose—parliament so easily agreed to his demand, or broadened the definition of treason as they did. It was not as if the change brought profit to Henry, as the act stipulated that forfeitures would go to the attainted man's lord, as was already the case with felony.[94] This, the legal scholar John Bellamy suggests, may have been Henry's means of persuading the Lords to support the measure, as in most cases they could expect to receive the goods and chattels of the convicted.[26] Bellamy considers, that although the act was an innovation in statute law, it still "managed to contain all the most obnoxious features of its varied predecessors".[26] Elton argues that, in spite of its perceived brutality, Cromwell—and therefore Henry—had a firm belief in the mechanisms and formalities of the common law",[95] except in "a few exceptional cases...where politics or [the King's] personal feelings played a major role".[95] If the Roose attainder had been the only example of its kind, argues Stacy, it may only be seen, with hindsight, as an abnormal legal curiosity.[96] But it was the first of several such circumventions of common law in Henry's reign, and calls into question, he says, whether the period should be seen as the age of legalism and due process, as Elton advocates.[96]

Stacy, arguing that the Roose case is the first example of an attainder intended to avoid dependency on common law,[61] states that although it has been overshadowed by subsequent higher profile individuals, it remained the legal precedent for those prosecutions.[97] Although attainder was already a common parliamentary weapon for late-medieval English Kings,[98] it was effectively a form of outlawry,[26] usually used to supplement a common law verdict with the confiscation of land and wealth as its intended result.[98] Lipscomb has argued though that not only were attainders increasingly used from the 1530s but that the decade shows the heaviest use of the mechanism in the whole of English history,[84] while Stacy suggests that Henrician ministers resorted to the parliamentary attainder as a matter of routine rather than last resort.[99] Attainders were popular with the King because they could take the place of common law rather than merely augment it, and thus avoided the necessity for evidential precision.[84] The Roose attainder laid the groundwork for the famous treason attainders—from supposed heretics such as Elizabeth Barton to the "great state offenders" such as Fisher, Thomas More, Cromwell, Surrey and two of Henry's own wives—that punctuated Henry's later reign.[100]

Cultural depiction

[edit]Shakespeare referenced Roose's execution in The Winter's Tale when the character of Paulina demands of King Leontes:[101]

What studied torments, tyrant, hast for me?

What wheels, racks, fires? What flaying? Boiling

In leads or oils? What old or newer torture

Must I receive...[102]

Poison, argues Bellany, was a popular motif among Shakespeare and his contemporaries as it tapped into a basic fear of the unknown, and poisoning stories were so often about more than merely the crime itself:[42]

Poisoning resonated or intersected with other transgressions: stories of poisoners were thus nearly always about more than just poison. Talk about poison crystallized profound (and growing) contemporary anxieties about order and identity, purity' and pollution, class and gender, self and other, the domestic and the foreign, politics and religion, appearance and reality, the natural and the supernatural, the knowable and the occult.[42]

Roose's attempt to poison Fisher is portrayed in the first episode of the second series of The Tudors, "Everything Is Beautiful", in 2008. Roose is played by Gary Murphy[103] in a "highly fictionalised" account of the case, in which the ultimate blame is placed on Wiltshire, played by Nick Dunning—who provides the poison—with Roose his catspaw.[104] The episode suggests that Roose is susceptible to bribery because he has three daughters for whom he wants good marriages. Having paid Roose to poison the soup, Wiltshire then threatens to exterminate the cook's family if he ever speaks of it again. Sir Thomas More takes the news of the poisoning to Henry, who becomes angry at the suggestion of Boleyn's involvement. Both Wiltshire and Cromwell witness what the critics Sue Parrill and William B. Robison have called the "particularly gruesome scene" where Roose is executed. Cromwell—despite having been shown the planner of the event—walks out halfway through.[105] Hilary Mantel includes the poisoning in her fictional life of Thomas Cromwell, Wolf Hall, from whose perspective events are related. Without naming Roose personally, Mantel covers the poisoning and its environs in some detail. She has Cromwell discover that the broth was poisoned and realise it was the only dish that the victims had had in common that night, which is then confirmed by the serving boys. Cromwell, while understanding that "there are poisons nature herself brews",[106] is in no doubt that a crime had been committed from the start. The cook, when captured, explains that "a man. A stranger who had said it would be a good joke" had given the cook the poison.[106]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Praemunire or praemunire facias (Ecclesiastical Latin: [prɛˈmuː.ni.rɛ ˈfaː.t͡ʃi.as]) was an offence in English law in which ecclesiastical bodies—which could range from Parish courts to those of the Pope—were deemed superior to those of the King.[6]

- ^ Chapuys' correspondence has been published as part of the Letters and Papers of the Reign of Henry VIII (HMSO, 1862–1932); the Roose episode is covered in volume five.[9]

- ^ Cited in Dowling 1999, p. 143.

- ^ The Bishops' of Rochester's house should not be confused with Lambeth Palace, the London seat of the Archbishops of Canterbury. Fisher's house stood on the old Lambeth Marsh Convent, adjacent to the Palace.[22]

- ^ Richard Hall, Life of Fisher, 1536.[29] Maria Dowling suggests that Hall received his information on the events of 1531 from a servant within Fisher's household at the time.[14]

- ^ The draft bill is held in the National Archives in Kew, classified as E 175/6/12.[48][49]

- ^ The act is 22 Hen. 8. c.9.[54]

- ^ Durham House occupied the spot where the Adelphi Buildings, built in the 18th century, now stands;[73] Wiltshire was living there from some time in 1529.[74]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Matusiak 2013, p. 72.

- ^ a b c Bridgett 1890, p. 215.

- ^ a b c d e Bayne 1921, p. 72.

- ^ Scarisbrick 1989, pp. 158–162.

- ^ Lehmberg 1970, p. vii.

- ^ a b Elton 1995, p. 339.

- ^ a b Pollard 1902, p. 220.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Bernard 2005, p. 110.

- ^ Reynolds 1955, p. 180 n. 1.

- ^ Bridgett 1890, p. 212.

- ^ Bernard 2005, p. 108.

- ^ a b c d e f Bellany 2016, p. 560.

- ^ a b c Norton 2008, p. 171.

- ^ a b c d e f Dowling 1999, p. 143.

- ^ a b c d e f Rex 2004.

- ^ a b Dowling 1999, p. 142.

- ^ a b Buckingham 2008, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Wilson, D. 2014, p. xvii.

- ^ Bellany 2016, p. 559.

- ^ Sim 2005, p. 78.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lehmberg 1970, p. 125.

- ^ Thompson 1989, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d Pettifer 1992, p. 163.

- ^ Stacy 1986a, p. 108.11.

- ^ Kesselring 2001, p. 895 n. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f Bellamy 2013, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Wilson, D. 2014, p. 1 n. 3.

- ^ a b c d e Stacy 1986b, p. 2.

- ^ Lehmberg 1970, p. 125 n. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Bridgett 1890, p. 213.

- ^ Reynolds 1955, p. 400.

- ^ a b Stacy 1986a, p. 88.

- ^ Bridgett 1890, p. 213 n.

- ^ a b c d e Wilson, D. 2014, p. 337.

- ^ a b c Bridgett 1890, p. 214.

- ^ a b Nichols 1852, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Lewis 1855, p. 73.

- ^ Matusiak 2019, p. 297.

- ^ a b c Stacy 1986b, p. 4.

- ^ Borman 2019, p. 123.

- ^ Wilson, D. 2014, p. l n. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Bellany 2016, p. 561.

- ^ a b Weinreich 2017, p. 209.

- ^ a b c Kesselring 2001, p. 894.

- ^ a b Stacy 1986a, p. 93.

- ^ Stacy 1986b, p. 14.

- ^ a b Williams 1979, p. 225.

- ^ Kesselring 2001, p. 898.

- ^ TNA 2019.

- ^ Kesselring 2001, pp. 896–897.

- ^ Kesselring 2001, p. 897.

- ^ Simpson 1965, p. 4.

- ^ a b Hutchinson 2005, p. 61.

- ^ Bridgett 1890, p. 214 n.

- ^ Wilson, D. 2014, pp. xvii–xviii.

- ^ Wilson, D. 2014.

- ^ a b Stacy 1986b, p. 5.

- ^ Kesselring 2000, p. 63.

- ^ a b Wilson, D. 2014, p. xxvii.

- ^ Cross 1917, p. 558.

- ^ a b Stacy 1986b, p. 1.

- ^ Stacy 1986b, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Bellany 2007, p. 144.

- ^ a b Walker 1980, p. 1076.

- ^ Bevan 1987, pp. 67–70.

- ^ a b c d e f Wilson, D. 2014, p. xviii.

- ^ Stacy 1986a, p. 87.

- ^ Andrews, William (13 July 1883), "The Many Modes of Execution", The Newcastle Weekly Courant

- ^ Dworkin 2002, p. 242.

- ^ Stacy 1986a, p. 91.

- ^ a b Burke 1872, p. 240.

- ^ a b c d e f Bayne 1921, p. 73.

- ^ Wheatley 2011, p. 542.

- ^ Wheeler 1937, p. 87.

- ^ Scarisbrick 1989, p. 166.

- ^ Scarisbrick 1956, p. 35.

- ^ HPO 2020.

- ^ Reynolds 1955, p. 180.

- ^ Buckingham 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Smith 1902, p. 419.

- ^ Kesselring 2003, p. 38.

- ^ Wilson, M. 2014, p. xvii.

- ^ Stacy 1986a, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d Lipscomb 2009, p. 194.

- ^ Williams 1979, p. 226.

- ^ Bellany 2004.

- ^ Wilson, D. 2014, pp. xxiv–xxv.

- ^ a b c Wilson, D. 2014, p. xxiv.

- ^ Stacy 1985, pp. 339–340.

- ^ Sim 2005, p. 326.

- ^ Stacy 1986b, p. 4 n. 19.

- ^ a b Wilson, D. 2014, p. xxvi.

- ^ Elton 1995, p. 60.

- ^ Kesselring 2001, p. 896.

- ^ a b Elton 1985, p. 399.

- ^ a b Stacy 1986b, p. 13.

- ^ Stacy 1986a, pp. 87, 106.

- ^ a b Bellamy 1970, pp. 181–205.

- ^ Stacy 1986b, p. 6.

- ^ Stacy 1986b, pp. 2, 7.

- ^ White 1911, p. 186.

- ^ Folger.

- ^ Robison 2016, p. 5.

- ^ Altazin 2016, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Parrill & Robison 2013, p. 260.

- ^ a b Mantel 2009.

Bibliography

[edit]- Altazin, K. (2016), "Fact, fiction and Fantasy: Conspiracy and Rebellion in The Tudors", in Robison, W. B. (ed.), History, Fiction, and The Tudors: Sex, Politics, Power, and Artistic License in the Showtime Television Series, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 223–235, ISBN 978-1-13743-881-2

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Bellamy, J. G. (1970), The Law of Treason in England in the Later Middle Ages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, OCLC 421828206

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Bellamy, J. G. (2013), The Tudor Law of Treason: An Introduction (repr. ed.), Oxford: Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-1-13467-216-5

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Bellany, A. (2004), "Carr [Kerr], Robert, Earl of Somerset (1585/6?–1645)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4754

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) - Bellany, A. (2007), The Politics of Court Scandal in Early Modern England: News Culture and the Overbury Affair, 1603–1660, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52103-543-9

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Bellany, A. (2016), Smuts, R. M. (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Age of Shakespeare, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 559–580, ISBN 978-0-19966-084-1

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Bernard, G. W. (2005), The King's Reformation: Henry VIII and the Remaking of the English Church, London: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-30012-271-8

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Bevan, A. S. (1987), "The Henrician Assizes and the Enforcement of the Reformation", in Eales, R.; Sullivan, D. (eds.), The Political Context of Law: Proceedings of the Seventh British Legal History Conference, Canterbury, 1985, London: Hambledon Press, pp. 61–76, ISBN 978-0-90762-884-2

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Borman, T. (2019), Henry VIII and the Men Who Made Him: The Secret History Behind the Tudor Throne, London: Hodder & Stoughton, ISBN 978-1-47364-991-0

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Bridgett, T. E. (1890), Life of Blessed John Fisher: Bishop of Rochester, Cardinal of the Holy Roman Church and Martyr under Henry VIII (2nd ed.), London: Burns & Oates, OCLC 635071290

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Buckingham, J. (2008), Bitter Nemesis: The Intimate History of Strychnine, London: CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-42005-316-6

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Burke, S. H. (1872), The Men and Women of the English Reformation, vol. 2, London: R. Washbourne, OCLC 676746646

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Cross, A. L. (1917), "The English Criminal Law and Benefit of Clergy during the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Century", The American Historical Review, 22 (3): 544–565, doi:10.2307/1842649, JSTOR 1842649, OCLC 1368063334

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Dowling, M. (1999), Fisher of Men: A Life of John Fisher, 1469–1535, London: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-23050-962-7

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Dworkin, Gerald (2002), "Patients and Prisoners: The Ethics of Lethal Injection", Analysis, 62 (2): 181–189, doi:10.1093/analys/62.2.181, OCLC 709962587

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Elton, G. R. (1985), Policy and Police: The Enforcement of the Reformation in the Age of Thomas Cromwell (2nd ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52131-309-4

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Elton, G. R. (1995), The Tudor Constitution: Documents and Commentary (3rd repr. ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-52128-757-9

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Hall, R. (1921) [1536], Bayne, R. (ed.), The Life of Fisher Transcribed from Ms. Harleian 6382, London: Early English Text Society, OCLC 2756917

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - HPO (2020), "The Reformation Parliament", History of Parliament Online, archived from the original on 19 April 2020, retrieved 19 April 2020

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Hutchinson, R. (2005), The Last Days of Henry VIII: Conspiracy, Treason and Heresy at the Court of the Dying Tyrant, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-29784-611-6

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Kesselring, K. J. (2000), To Pardon and To Punish: Mercy and Authority in Tudor England (PhD thesis), Queen's University Ontario, OCLC 1006900357

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Kesselring, K. J. (2001), "A Draft of the 1531 'Acte for Poysoning'", The English Historical Review, 116 (468): 894–899, doi:10.1093/ehr/CXVI.468.894, OCLC 1099048890

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Kesselring, K. J. (2003), Mercy and Authority in the Tudor State, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-13943-662-5

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Lehmberg, S. E. (1970), The Reformation Parliament 1529–1536, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-5210-7655-5

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Lewis, J. (1855), The Life of Dr. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, in the Reign of King Henry VIII., London: J. Lilly, OCLC 682392019

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Lipscomb, S. (2009), 1536: The Year that Changed Henry VIII, Oxford: Lion Books, ISBN 978-0-74595-332-8

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Mantel, H. (2009), Wolf Hall, London: Fourth Estate, ISBN 978-0-00729-241-7

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Matusiak, J. (2013), Henry VIII: The Life and Rule of England's Nero, Cheltenham: History Press, ISBN 978-0-75249-707-5

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Matusiak, J. (2019), Martyrs of Henry VIII: Repression, Defiance, Sacrifice, Cheltenham: History Press, ISBN 978-0-75099-354-8

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Nichols, J. G., ed. (1852), Chronicle of the Grey Friars of London, London: Camden Society, OCLC 906285546

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Norton, E. (2008), Anne Boleyn: Henry VIII's Obsession, Stroud: Amberley, ISBN 978-1-44560-663-7

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Parrill, S.; Robison, W. B. (2013), The Tudors on Film and Television, London: McFarland, ISBN 978-0-78645-891-2

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Pettifer, E. W. (1992), Punishments of Former Days, Winchester: Waterside Press, ISBN 978-1-87287-005-2

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Pollard, A. F. (1902), Henry VIII, London: Goupil, OCLC 1069581804

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Rex, R. (2004), "Fisher, John [St John Fisher] (c. 1469–1535)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9498

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) - Reynolds, E. E. (1955), St. John Fisher, London: Burns & Oates, OCLC 233703232

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Ribadeneyra, P. de (2017), Weinreich S. J. (ed.), Pedro de Ribadeneyra's 'Ecclesiastical History of the Schism of the Kingdom of England': A Spanish Jesuit's History of the English Reformation, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-9-00432-396-4

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Robison, W. B. (2016), "Introduction", in Robison, W.B. (ed.), History, Fiction, and The Tudors: Sex, Politics, Power, and Artistic License in the Showtime Television Series, New York City: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–26, ISBN 978-1-13743-881-2

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Scarisbrick, J. J. (1956), "The Pardon of the Clergy, 1531", The Cambridge Historical Journal, 12: 22–39, doi:10.1017/S1474691300000317, OCLC 72660714

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Scarisbrick, J. J. (1989), "Fisher, Henry VIII and the Reformation Crisis", in Bradshaw, B.; Duffy, E. (eds.), Humanism, Reform and the Reformation: The Career of Bishop John Fisher, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 155–168, ISBN 978-0-52134-034-2

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Shakespeare, W., The Winter's Tale 3.2/194–197, Folger Shakespeare Library

- Sim, A. (2005), Food & Feast in Tudor England, Stroud: Sutton, ISBN 978-0-75093-772-6

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Simpson, A. W. B. (1965), "The Equitable Doctrine of Consideration and the Law of Uses", University of Toronto Law Journal, 16 (1): 1–36, doi:10.2307/825093, JSTOR 825093, OCLC 54524962

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Smith, C. M. (1902), A Treatise on the Law of Master and Servant: Including Therein Masters and Workmen in Every Description of Trade and Occupation; with an Appendix of Statutes (5th ed.), London: Sweet & Maxwell, OCLC 2394906

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Stacy, W. R. (1985), "Matter of Fact, Matter of Law, and the Attainder of the Earl of Strafford", American Journal of Legal History, 29 (4): 323–348, doi:10.2307/845534, JSTOR 845534, OCLC 1124378837

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Stacy, W. R. (1986a), The Bill of Attainder in English History (PhD thesis), University of Wisconsin-Madison, OCLC 753814488

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Stacy, W. R. (1986b), "Richard Roose and the Use of Parliamentary Attainder in the Reign of Henry VIII", The Historical Journal, 29: 1–15, doi:10.1017/S0018246X00018598, OCLC 863011771, S2CID 159730930

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - TNA, "E 175/6 /12" (1531) [manuscript], Exchequer: King's Remembrancer and Treasury of the Receipt: Parliament and Council Proceedings, Series II, Series: E 175, p. Bill concerning poisoning, Kew: The National Archives

- Thompson, S. (1989), "The Bishop in his Diocese", in Bradshaw, B.; Duffy, E. (eds.), Humanism, Reform and the Reformation: The Career of Bishop John Fisher, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 67–80, ISBN 978-0-52134-034-2

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Walker, D. M. (1980), The Oxford Companion to Law, Oxford: Clarendon Press, ISBN 978-0-19866-110-8

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Wheatley, H. B. (2011), London Past and Present: Its History, Associations, and Traditions (repr. ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-10802-806-6

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Wheeler, E. W. (1937), The Parish of St. Martin-in-the-Fields: The Strand, London: London County Council, OCLC 276645776

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - White, E. J. (1911), Commentaries on the Law in Shakespeare, St. Louis: The F.H. Thomas Law Book Co., OCLC 249772177

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Williams, P. (1979), The Tudor Regime, Oxford: Clarendon Press, OCLC 905291838

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Wilson, Derek (2014), In The Lion's Court: Power, Ambition and Sudden Death in the Reign of Henry VIII, London: Random House, ISBN 978-0-75355-130-1

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link) - Wilson, Miranda (2014), Poison's Dark Works in Renaissance England, Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, ISBN 978-1-61148-539-4

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: overridden setting (link)

External links

[edit]- "Letters and Papers, Henry VIII", British History Online, archived from the original on 21 November 2019, retrieved 19 November 2019

- "The Statutes of the Realm: An Acte for Poysonyng", Haithi Trust, 1963, archived from the original on 22 November 2019, retrieved 22 November 2019