Collectivist anarchism

| Part of a series on |

| Anarchism |

|---|

|

Collectivist anarchism,[1] also called anarchist collectivism[2] and anarcho-collectivism,[3] is an anarchist school of thought that advocates the abolition of both the state and private ownership of the means of production. In their place, it envisions both the collective ownership of the means of production and the entitlement of workers to the fruits of their own labour,[4] which would be ensured by a societal pact between individuals and collectives.[5] Collectivists considered trade unions to be the means through which to bring about collectivism through a social revolution, where they would form the nucleus for a post-capitalist society.[6]

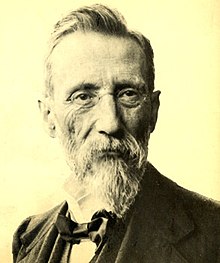

The tendency was initially conceived as a synthesis of social equality and liberty, by the Russian revolutionary socialist Mikhail Bakunin.[7] It is commonly associated with the anti-authoritarian sections of the International Workingmen's Association and the early Spanish anarchist movement, with whom it continued to hold a strong influence until the end of the 19th century. Eventually, it was supplanted as the dominant tendency of anarchism by anarcho-communism, which advocated for the abolition of wages and the distribution of resources "from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs".

History

[edit]

Collectivist anarchism was first formulated within the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), under the influence of Mikhail Bakunin.[8] Bakunin had been inspired by the traditional agrarian collectivism practiced by the Russian peasantry and wished to see its principles of mutual aid applied to industrial society, which he hoped to mobilise in favour of liberty and social equality.[9] According to Friedrich Engels, Bakunin's collectivism represented a synthesis of Karl Marx's communism and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon's mutualism.[10] Bakunin rejected the communist principle of "from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs", considering instead that resources would have to be distributed according to one's own labour. While Bakunin accepted Proudhon's organisational theory of federalism, he also rejected the mutualist centring of the independent artisan, instead considering the collective to be the base social unit for organising society.[11]

Bakunin's collectivism had widespread appeal in Spain, where industrial workers and rural peasants found inspiration in its precepts of decentralisation and direct action.[12] From the outset of anarchism's introduction to Spain in 1868,[13] Spanish anarchists largely subscribed to collectivism, inspired by Bakunin's anarchist doctrine,[14] while also drawing from the anti-authoritarianism and federalism espoused by Francesc Pi i Margall.[15] Pi's influence on the collectivists was most pronounced in the work of Juan Serrano Oteiza, an early convert to collectivist anarchism who envisaged a federal society that upheld the autonomy of the individual, trade union and municipality.[16] But Serrano's collectivism differed from Pi's federalism by rejecting reformist political parties and instead upholding the working class as the agents of revolutionary change.[17]

By the 1870s, the Spanish Regional Federation of the International Workingmen's Association (FRE-AIT) had widely disseminated the doctrine of collectivist anarchism, with its principles being widely adopted by workers' societies, many of which were not even anarchist themselves.[18] Following the collapse of the FRE-AIT, in 1881, the Barcelona branch reconstituted the organisation as the Federation of Workers of the Spanish Region (FTRE), which was established according to the principles of collectivist anarchism.[19]

Break with anarcho-communism

[edit]While anarchist theory in Spain remained stagnant, with collectivist positions staying largely unchanged, the international anarchist movement developed towards anarcho-communism and many anarchists began to adopt the theory of propaganda of the deed,[20] in a process spearheaded by the Italian anarchists. [21] Within the Jura Federation, collectivists led by Adhémar Schwitzguébel resisted the adoption of communism, but the transition from collectivism to communism went by largely without controversy. However, in Spain, where collectivist anarchists had been uniquely successful within the trade unionist movement, collectivism maintained its foothold for much longer than in other countries. It was only when their trade union activities began to be suppressed that the Spanish anarchists gravitated towards communism.[22]

The anarcho-communists criticized the collectivist model of workers' entitlement to the fruit of their labour, which they believed would disenfranchise non-producers and risk creating a new ruling class that determined wages. Instead, they advocate for the abolition of wage labour and its replacement with a system of solidarity, where all property was held in common.[23] This development of collectivism into communism had been preceded by the writings of James Guillaume, who outlined a post-capitalist system where resources would be distributed "from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs", while the collectivist system would be used during the transition out of capitalism.[24] In organizational terms, the communists opposed the trade unions advocated by the collectivists, viewing them as fundamentally reformist and bureaucratic, and thus as incompatible with anti-authoritarian models of organization.[25] Instead, the communists preferred small affinity groups that could carry out violent attacks against the economic order, upholding the theory of propaganda of the deed.[26]

In 1884, the Seville Congress of the FTRE resulted in many anarchists leaving the organisation, as they no longer believed it to be the best vehicle for organising the working class towards a social revolution. This preceded a complete break between Spanish collectivists and communists, which took place the following year.[27] Serrano attempted to defend the collectivism of the FTRE from the rise of communism, considering the two tendencies to be irreconcilably opposed to each other.[28] But Serrano's arguments were unsuccessful in rallying support, as the more moderate collectivism began to give way to the more radical communism.[29] Public debates on the merits of the two systems also lay the groundwork for the development of an intellectual tradition in Spanish anarchism.[30]

Decline of collectivism

[edit]The rise of communism, which challenged the collectivist principles of the FTRE, eventually resulted in the organisation's dissolution.[31] In 1888, the Catalan regional federation of the FTRE was reorganised into the Union and Solidarity Pact, which nominally retained a collectivist orientation, but accepted members from all tendencies.[32] The collectivist Ricardo Mella opposed the formation of the Pact, as he considered it to be a fundamentally communist organisation and worried it would undermine the FTRE.[33] The collapse of the FTRE marked the supplanting of collectivism as the dominant anarchist ideology in Spain, as the communists consolidated control over the movement.[34] Mella hoped to reconstitute the FTRE, refusing to even recognise its dissolution and proposing its reorganisation along more decentralised lines.[35] But his efforts were ultimately futile, as most Spanish collectivists supported the dissolution of the FTRE.[36]

In the years that followed, efforts were made in the libertarian press to reconcile the split.[37] In the pages of El Productor, the collectivist Cels Gomis i Mestre made appeals against dogmatism.[38] Anarchists that opposed the schism eventually went on to establish the tendency of "anarchism without adjectives", in order to overcome the ideological disputes between the two factions.[39] The collectivist-communist debate also inspired Errico Malatesta to develop towards a pluralist conception of anarchism.[40] Although he personally favoured anarcho-communism, he distinguished between his desired ends and the means by which the social revolution would take place, believing that the organisation of society should be left to spontaneous development.[41] He thus proposed a union between communists and collectivists, based on a common tactical line, arguing against dogmatism as an authoritarian instinct.[42] But in spite of his pluralist inclinations, Malatesta continued to argue against collectivism, considering it to be incompatible with anarchism.[43]

By the end of the 19th century, collectivism had been reduced to a minority tendency in Spain, subsumed by anarcho-communism.[44] This also gave way to the development of anarcho-syndicalism, which united community and labour organizing, overcoming both the localism of the collectivists and the conspiratorial nature of the communists.[45]

Later developments

[edit]Collectivist anarchism remained prominent in the rural areas of Andalusia, where local skilled workers were attracted to the promises of collective labour, with individual ownership over the fruits of that labour.[46] During the Spanish Revolution of 1936, many of the ideas proposed by collectivist anarchism were put into practice, as the advance of the confederal militias gave way to the widespread collectivization of agriculture (around 35-40%) throughout the Spanish Republic.[47]

Modern descendants of collectivist anarchism include participatory economics, as advocated by Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel, which takes up the collectivist model of remuneration.[48]

People

[edit]See also

[edit]- Anarchist Catalonia

- Anarchist schools of thought

- Anarcho-communism

- Anarcho-syndicalism

- Free association (Marxism and anarchism)

- Participatory economics

- Spanish Revolution of 1936

- Workers' council

- Workers' self-management

References

[edit]- ^ Avrich, Paul (1995) [2005]. Anarchist Voices: An Oral History of Anarchism in America. AK Press. p. 3. "All in all a wide range of views is represented: individualist anarchism, mutualist anarchism, collectivist anarchism, communist anarchism, and syndicalist anarchism, to mention only the most conspicuous." ISBN 978-1904859277.

- ^ Kropotkin, Peter. (1905) [1987]. Anarchism and Anarchist Communism. Freedom Press. p. 19.

- ^ Buckley, A. M. (2011). Anarchism. Essential Library. p. 97. "Collectivist anarchism, also called anarcho-collectivism, arose after mutualism." ISBN 978-1617147883.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 104–105; Martin 1990, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 104–105.

- ^ a b Esenwein 1989, p. 106.

- ^ Morris 1993, p. 115.

- ^ Turcato 2012, p. 51.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Morris 1993, p. 76.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 106; Martin 1990, p. 88.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 101–103.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Martin 1990, p. 95.

- ^ Martin 1990, p. 84.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 107; Turcato 2012, p. 51.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 108.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 109.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 113.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 115.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 118.

- ^ Bookchin 1978, p. 117; Esenwein 1989, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b Esenwein 1989, p. 120.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 122.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, p. 123.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 126–127.

- ^ a b Esenwein 1989, p. 127.

- ^ Ackelsberg 2005, pp. 62–63; Esenwein 1989, p. 99.

- ^ Turcato 2012, pp. 51–53.

- ^ Turcato 2012, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Turcato 2012, p. 53.

- ^ Turcato 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Ackelsberg 2005, p. 69; Martin 1990, p. 88.

- ^ Ackelsberg 2005, p. 69.

- ^ Ackelsberg 2005, p. 68.

- ^ Martin 1990, p. 393.

- ^ Shannon 2018, p. 101.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 101–107.

- ^ Esenwein 1989, pp. 99, 106.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ackelsberg, Martha A. (2005) [1991]. Free Women of Spain. AK Press. ISBN 978-1902593968.

- Bookchin, Murray (1978). The Spanish Anarchists. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-090607-3.

- Esenwein, George Richard (1989). Anarchist Ideology and the Working-class Movement in Spain, 1868-1898. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520063983.

- Martin, Benjamin (1990). The Agony of Modernization: Labor and Industrialization in Spain. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0875461656.

- Morris, Brian (January 1993). Bakunin: The Philosophy of Freedom. Black Rose Books. ISBN 978-1-895431-66-7.

- Shannon, Deric (2018). "Anti-Capitalism and Libertarian Political Economy". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 91–106. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_5. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 158841066.

- Turcato, Davide (2012). Making Sense of Anarchism: Errico Malatesta's Experiments with Revolution, 1889-1900. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230301795.

- Turcato, Davide (2018). "Anarchist Communism". In Adams, Matthew S.; Levy, Carl (eds.). The Palgrave Handbook of Anarchism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 237–247. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75620-2_13. ISBN 978-3319756196. S2CID 242094330.

Further reading

[edit]- Blonna, Alex (1977). Marxism and Anarchist Collectivism in the International Workingman's Association, 1864-1872 (Thesis). Chico: California State University. OCLC 6221011.

- Heywood, Andrew (16 February 2017). "Anarchism". Political Ideologies: An Introduction (6th ed.). Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 146.

- Maximoff, G. P. (1964) [1953]. The Political Philosophy of Bakunin. Macmillan Publishers.

External links

[edit]- "The Collectivist Wages System" entry at the Anarchy Archives. Anarcho-communist Peter Kropotkin's criticism of collectivist anarchism from The Conquest of Bread (1892).