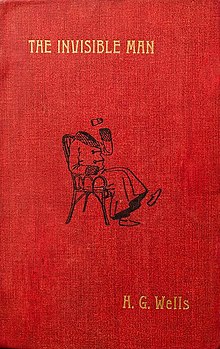

The Invisible Man

First edition cover (UK) | |

| Author | H. G. Wells |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction novel |

| Published | 1897 |

| Publisher | C. Arthur Pearson (UK) Edward Arnold (US) |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 149 |

| Text | The Invisible Man at Wikisource |

The Invisible Man is an 1897 science fiction novel by British writer H. G. Wells. Originally serialised in Pearson's Weekly in 1897, it was published as a novel the same year. The Invisible Man to whom the title refers is Griffin, a scientist who has devoted himself to research into optics and who invents a way to change a body's refractive index to that of air so that it neither absorbs nor reflects light. He carries out this procedure on himself and renders himself invisible, but fails in his attempt to reverse it. A practitioner of random and irresponsible violence, Griffin has become an iconic character in horror fiction.

While its predecessors, The Time Machine and The Island of Doctor Moreau, were written using first-person narrators, Wells adopts a third-person objective point of view in The Invisible Man. The novel is considered influential, and helped establish Wells as the "father of science fiction".[1]

Plot summary

[edit]A man named Griffin arrives at an inn owned by Mr. and Mrs. Hall of the English village of Iping, West Sussex, during a snowstorm. He wears a wide-brimmed hat, a long-sleeved, thick coat and gloves; his face is hidden entirely by bandages except for a prosthetic nose. He is reclusive, irascible, unfriendly, and introverted. He demands to be left alone and spends most of his time in his rooms working with chemicals and laboratory apparatus, only venturing out at night. He causes a lot of accidents, but when Mrs. Hall addresses this, Griffin demands that the cost of the damage be put on his bill. While he is staying at the inn, hundreds of glass bottles arrive. His odd behaviour becomes the talk of the village, with many theorizing as to his origins.

Meanwhile, a burglary occurs in the village, but no suspect is found. Running short of money, Griffin is unable to pay for his lodging and meals. When his landlady threatens to kick him out, he reveals his invisibility to her in a fit of anger. An attempt to apprehend him by the police is thwarted when he undresses to take advantage of his invisibility, fights off his would-be captors, and flees.

At the South Downs, Griffin coerces a tramp, Thomas Marvel, to become his assistant. With Marvel, he returns to the village to recover three notebooks that contain records of his experiments. Marvel attempts to betray Griffin, who threatens to kill him. Marvel escapes to the seaside town of Port Burdock, pursued to an inn by Griffin, who is shot by one of the bar patrons.

Griffin takes shelter in a nearby house that turns out to belong to Dr. Kemp, a former acquaintance from medical school. To Kemp, he reveals his true identity: an albino former medical student who left medicine to devote himself to the science of optics.

Griffin tells the story of how he invented chemicals capable of rendering bodies invisible, which he first tried on a cat, then himself, how he burned down the boarding house he was staying in to cover his tracks, found himself ill-equipped to survive in the open, stole clothes from a theatrical supply shop on Drury Lane, and then headed to Iping to attempt to reverse the invisibility. Having been driven unhinged by the procedure and his experiences, Griffin now imagines that he can make Kemp his secret confederate, describing a plan to use his invisibility to terrorise the nation.

Kemp has already denounced Griffin to the local authorities, led by Port Burdock's chief of police, Colonel Adye, and waits for help to arrive while listening to this wild proposal. When Adye and his men arrive, Griffin fights his way out and the next day leaves a note announcing that Kemp will be the first man to be killed in the "Reign of Terror". Kemp tries to organise a plan to use himself as bait to trap the invisible man, but a note that he sends is stolen from his servant by Griffin. During the chase, Griffin arms himself with an iron bar and kills a bystander.[2]

Griffin shoots Adye, then breaks into Kemp's house. Adye's constables fend him off and Kemp bolts for the town, where the locals come to his aid. Still obsessed with killing Kemp, Griffin nearly strangles him but is cornered, seized, and beaten by the enraged mob, his last words a cry for mercy. Kemp urges the mob to stand away and tries to save Griffin's life, though unsuccessfully. Griffin's battered body becomes visible as he dies. A policeman has someone cover Griffin's face with a sheet.

It is later revealed that Marvel has secretly kept Griffin's notes and—with the help of the stolen money— becomes a successful businessman, running the "Invisible Man Inn". However, when not running his inn, Marvel tries to decipher the notes, hoping of one day recreating Griffin's work. However, because pages were accidentally washed clean, and the remaining notes are coded in Greek and Latin, and Marvel has no comprehension of even the basic mathematical symbols he sees in the notes, this is unlikely.[2]

Background

[edit]According to John Sutherland, Wells and his contemporaries such as Arthur Conan Doyle, Robert Louis Stevenson and Rudyard Kipling "essentially wrote boy's books for grown-ups." Sutherland identifies The Invisible Man as one such book.[3] Wells said that his inspiration for the novella was "The Perils of Invisibility", one of the Bab Ballads by W. S. Gilbert, which includes the couplet "Old Peter vanished like a shot/but then – his suit of clothes did not."[4] Another influence on The Invisible Man was Plato's Republic, a book which had a significant effect on Wells when he read it as an adolescent. In the second book of the Republic, Glaucon recounts the legend of the Ring of Gyges, which posits that, if a man were made invisible and could act with impunity, he would "go about among men with the powers of a god."[5] Wells wrote the original version of the tale between March and June 1896. This version was a 25,000 word short story titled "The Man at the Coach and Horses" with which Wells was dissatisfied, so he extended it.[6]

Scientific accuracy

[edit]Russian writer Yakov I. Perelman pointed out in Physics Can Be Fun (1962) that from a scientific point of view, a man made invisible by Griffin's method should have been blind because a human eye works by absorbing incoming light, not letting it through completely. Wells seems to show some awareness of this problem in Chapter 20, where the eyes of an otherwise invisible cat retain visible retinas. Nonetheless, this would be insufficient because the retina would be flooded with light (from all directions) that ordinarily is blocked by the opaque sclera of the eyeball. Also, any image would be badly blurred if the eye had an invisible cornea and lens.

Legacy

[edit]The Invisible Man has been adapted for, and referred to in, film, television, audio drama, and comics. Allen Grove, professor of English at Alfred University states,

The Invisible Man has a wealth of progeny. The novel was adapted into comic book form by Classics Illustrated in the 1950s, and by Marvel Comics in 1976. Many writers and film-makers also created sequels to the story, something the novel’s ambiguous ending encourages. Over a dozen movies and television series are based on the novel, including a 1933 James Whale film and a 1984 series by the BBC. The novel has been adapted for radio numerous times, including a 2017 audio version starring John Hurt as the invisible man. It was adapted by playwright Arthur Yorinks in 2009 for WNYC's The Greene Space setting the multimedia play in a New York City homeless shelter. The cultural pervasiveness of The Invisible Man has led to everything from his cameo in an episode of Tom and Jerry to the Queen song "The Invisible Man".[7]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Westfahl, Gary, ed. (2009). The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination. Critical Explorations in Science Fiction and Fantasy. McFarland & Company. p. 41. ISBN 978-0786437221.

- ^ a b Wells, H. G. (1897). "Epilogue". The Invisible Man. London: C. Arthur Pearson Ltd.

The covers are weather-worn and tinged with an algal green--for once they sojourned in a ditch and some of the pages have been washed blank by dirty water.

- ^ Wells 1996, p. xv.

- ^ Wells 1996, p. xviii.

- ^ Wells 2017a, p. xvii.

- ^ Wells 1996, p. xxix.

- ^ Wells, H.G. (2017b). The Time Machine and The Invisible Man. Race Point Publishing. p. xvi.

Bibliography

[edit]- Wells, H. G. (1996), The Invisible Man, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-283195-X

- Wells, H. G. (2017a), The Invisible Man, Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-870267-2

External links

[edit]- The Invisible Man at Standard Ebooks

- The Invisible Man at Project Gutenberg

The Invisible Man public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Invisible Man public domain audiobook at LibriVox- 3 may 2006 guardian article about Milton and Nicorovici's invention

- Horror-Wood: Invisible Man films

- Complete copy of The Invisible Man by HG Wells in HTML, ASCII and WORD, archived from the original on 18 April 2021

- The Invisible Man

- 1897 British novels

- British horror novels

- British novellas

- British science fiction novels

- 1897 science fiction novels

- Novels by H. G. Wells

- Novels set in London

- Novels set in Sussex

- Fiction about invisibility

- Novels first published in serial form

- British novels adapted into plays

- British novels adapted into films

- Novels adapted into radio programs

- British novels adapted into television shows

- Novels adapted into comics

- Human experimentation in fiction

- Science fiction novels adapted into films

- 1890s fiction books