General Government

General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region Generalgouvernement für die besetzten polnischen Gebiete (German) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939–1945 | |||||||||||||

The General Government in 1942 | |||||||||||||

| Status | Administratively autonomous component of Germany[1] | ||||||||||||

| Capital | Litzmannstadt (12 October – 4 November 1939) Krakau (4 November 1939 – 19 January 1945) | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | German (official) Polish, Ukrainian, Yiddish | ||||||||||||

| Government | Civil administration | ||||||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||||||

• 1939–1945 | Hans Frank | ||||||||||||

| Secretary for State | |||||||||||||

• 1939–1940 | Arthur Seyss-Inquart | ||||||||||||

• 1940–1945 | Josef Bühler | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Occupation of Poland in World War II | ||||||||||||

| 1 September 1939 | |||||||||||||

• Establishment | 26 October 1939 | ||||||||||||

• Galicia added | 1 August 1941 | ||||||||||||

| 22 July 1944 | |||||||||||||

| 17 January 1945 | |||||||||||||

• Disintegration | 19 January 1945 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Zloty Reichsmark | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Poland Ukraine | ||||||||||||

The General Government (German: Generalgouvernement; Polish: Generalne Gubernatorstwo; Ukrainian: Генеральна губернія), formally the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (German: Generalgouvernement für die besetzten polnischen Gebiete), was a German zone of occupation established after the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, Slovakia and the Soviet Union in 1939 at the onset of World War II. The newly occupied Second Polish Republic was split into three zones: the General Government in its centre, Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany in the west, and Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union in the east. The territory was expanded substantially in 1941, after the German Invasion of the Soviet Union, to include the new District of Galicia.[2] The area of the Generalgouvernement roughly corresponded with the Austrian part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth after the Third Partition of Poland in 1795.

The basis for the formation of the General Government was the "Annexation Decree on the Administration of the Occupied Polish Territories". Announced by Hitler on October 8, 1939, it claimed that the Polish government had totally collapsed. This rationale was utilized by the German Supreme Court to reassign the identity of all Polish nationals as stateless subjects, with the exception of the ethnic Germans of interwar Poland—who, disregarding international law, were named the only rightful citizens of Nazi Germany.[2]

The General Government was run by Germany as a separate administrative unit for logistical purposes. When the Wehrmacht forces invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941 (Operation Barbarossa), the area of the General Government was enlarged by the inclusion of the Polish regions previously annexed to the USSR.[3] Within days East Galicia was overrun and incorporated into the District of Galicia. Until 1945, the General Government comprised much of central, southern, and southeastern Poland within its prewar borders (and of modern-day Western Ukraine), including the major Polish cities of Warsaw, Kraków, Lwów (now Lviv, renamed Lemberg), Lublin (see Lublin Reservation), Tarnopol (see history of Tarnopol Ghetto), Stanisławów (now Ivano-Frankivsk, renamed Stanislau; see Stanisławów Ghetto), Drohobycz, and Sambor (see Drohobycz and Sambor Ghettos) and others. Geographical locations were renamed in German.[2]

The administration of the General Government was composed entirely of German officials, with the intent that the area was to be colonized by Germanic settlers who would reduce the local Polish population to the level of serfs before their eventual genocide.[4] The Nazi German rulers of the Generalgouvernement had no intention of sharing power with the locals throughout the war, regardless of their ethnicity and political orientation. The authorities rarely mentioned the name Poland in legal correspondence. The only exception to this was the General Government's Bank of Issue in Poland (Polish: Bank Emisyjny w Polsce, German: Emissionbank in Polen).[5][6]

Name

The full title of the regime in Germany until July 1940 was the Generalgouvernement für die besetzten polnischen Gebiete, a name that is usually translated as "General Government for the Occupied Polish Territories". Governor Hans Frank, on Hitler's authority, shortened the name on 31 July 1940 to just Generalgouvernement.[7]

An accurate English translation of Generalgouvernement, which is a borrowing from French, is 'General Governorate', cognate with the Dutch Generaliteitslanden. A more accurate English translation of the French term gouvernement in this context is not 'government', but "governorate", which is a type of a territory that is administered centrally. In the French and Dutch original, the 'General' in the name is a reference to the Estates-General, the central assembly which was given an authority to directly rule the territory.

The Nazi designation of Generalgouvernement also gave a nod to the once existing Generalgouvernement Warschau, a civil entity created in the invaded Russian Empire territory by the German Empire during World War I. This district existed from 1914 to 1918 together with an Austro-Hungarian-controlled Military Government of Lublin alongside the short-lived Kingdom of Poland of 1916–1918, a similar rump state formed out of the then-Russian-controlled parts of Poland.[8]

The General Government area was also known colloquially as the Restpolen ('Remainder of Poland').

History

After Germany's attack on Poland, all areas occupied by the German army including the Free City of Danzig initially came under military rule. This area extended from the 1939 eastern border of Germany proper and of East Prussia up to the Bug River where the German armies had halted their advance and linked up with the Soviet Red Army in accordance with their secret pact against Poland.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact signed on 23 August 1939 had promised the vast territory between the Vistula and Bug rivers to the Soviet "sphere of influence" in divided Poland, while the two powers would have jointly ruled Warsaw. To settle the deviation from the original agreement, the German and Soviet representatives met again on September 28 to delineate a permanent border between the two countries. Under this revised version of the pact the territory concerned was exchanged for the inclusion in the Soviet sphere of Lithuania, which had originally fallen within the ambit of Germany. With the new agreement the entire central part of Poland, including the core ethnic area of the Poles, came under exclusively German control.

Hitler decreed the direct annexation to the German Reich of large parts of the occupied Polish territory in the western half of the German zone, in order to increase the Reich's Lebensraum.[9] Germany organized most of these areas as two new Reichsgaue: Danzig-West Prussia and Wartheland. The remaining three regions, the so-called areas of Zichenau, Eastern Upper Silesia and the Suwałki triangle, became attached to adjacent Gaue of Germany. Draconian measures were introduced by both RKF and HTO,[a] to facilitate the immediate Germanization of the annexed territory, typically resulting in mass expulsions, especially in the Warthegau. The remaining parts of the former Poland were to become a German Nebenland (March, borderland) as a frontier post of German rule in the east. A Führer's decree of October 12, 1939 established the General Government; the decree came into force on October 26, 1939.[2]

Hans Frank was appointed as the governor-general of the General Government. German authorities made a sharp contrast between the new Reich territory and a supposedly occupied rump state that could serve as a bargaining chip with the Western powers. The Germans established a closed border between the two German zones to heighten the difficulty of cross-frontier communication between the different segments of the Polish population.

The official name chosen for the new entity was the Generalgouvernement für die besetzten polnischen Gebiete (General Government for the Occupied Polish Territories), then changed to the Generalgouvernement (General Government) by Frank's decree of July 31, 1940. However, this name did not imply anything about the actual nature of the administration. The German authorities never regarded these Polish lands (apart from the short period of military administration during the actual invasion of Poland) as an occupied territory.[10] The Nazis considered the Polish state to have effectively ceased to exist with its defeat in the September campaign.

Overall, 4 million of the 1939 population of the General Government area had lost their lives by the time the Soviet armed forces entered the area in late 1944. If the Polish underground killed a German, 50–100 Poles were executed by German police as a punishment and as a warning to other Poles.[11] Most of the Jews, perhaps as many as two million, had also been rounded up and murdered. Germans destroyed Warsaw after the Warsaw Uprising. As the Soviets advanced through Poland in late 1944 the General Government collapsed. American troops captured Hans Frank, who had governed the region, in May 1945; he became one of the defendants at the Nuremberg Trials. During his trial he resumed his childhood practice of Catholicism and expressed repentance. Frank surrendered forty volumes of his diaries to the Tribunal; much evidence against him and others was gathered from them. He was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity. On October 1, 1946, he was sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out on October 16.

German intentions regarding the region

The conversion of Warsaw into a "model city" was planned in 1940 and later, in similar ways like the conversion of Berlin was planned. In March 1941 Hans Frank informed his subordinates that Hitler had made the decision to "turn this region into a purely German area within 15–20 years". He explained: "Where 12 million Poles now live, is to be populated by 4 to 5 million Germans. The Generalgouvernement must become as German as the Rhineland."[5] By 1942 Hitler and Frank had agreed that the Kraków ("with its purely German capital") and Lublin districts would be the first areas for German colonists to re-populate.[12] Hitler stated: "When these two weak points have been strengthened, it should be possible to slowly drive back the Poles."[12] Peculiar about these statements is the circumstance that there were not enough German settlers to even make the Wartheland "as German as the Rhineland". According to notes from Martin Bormann German policy envisaged reducing lower-class Poles to the status of serfs, while deporting or otherwise eliminating the middle and upper classes and eventually replacing them with German colonists of the "master race".

The General Government is our work force reservoir for lowgrade work (brick plants, road building, etc.) ... Unconditionally, attention should be paid to the fact that there can be no "Polish masters"; where there are Polish masters, and I do not care how hard this sounds, they must be killed. (...) The Führer must emphasize once again that for Poles there is only one master and he is a German, there can be no two masters beside each other and there is no consent to such, hence all representatives of the Polish intelligentsia are to be killed ... The General Government is a Polish reservation, a great Polish labor camp. — Note of Martin Bormann from the meeting of Dr. Hans Frank with Adolf Hitler, Berlin, 2 October 1940.[13]

German bureaucrats drew up various plans regarding the future of the original population. One called for the deportation of about 20 million Poles to western Siberia, and the Germanisation of 4 to 5 million; although deportation in reality meant many Poles were to be put to death, a small number would be "Germanized", and young Poles of desirable qualities would be kidnapped and raised in Germany.[14] In the General Government, all secondary education was abolished and all Polish cultural institutions closed.[citation needed]

In 1943, the government selected the Zamojskie area for further Germanization on account of its fertile black soil, and German colonial settlements were planned. Zamość was initially renamed by the government to Himmlerstadt (Himmler City), which was later changed to Pflugstadt (Plough City), both names were not implemented. Most of the Polish population was expelled by the Nazi occupation authorities with documented brutality. Himmler intended the city of Lublin to have a German population of 20% to 25% by the beginning of 1944, and of 30% to 40% by the following year, at which time Lublin was to be declared a German city and given a German mayor.[15]

Territorial dissection

Nazi planners never definitively resolved the question of the exact territorial reorganization of the Polish provinces in the event of German victory in the east. Germany had already annexed large parts of western pre-war Poland (8 October 1939) before the establishment of the General Government (26 October 1939), and the remaining region was also intended to be directly incorporated into the German Reich at some future date. The Nazi leadership discussed numerous initiatives with this aim.

The earliest such proposal (October/November 1939) called for the establishment of a separate Reichsgau Beskidenland which would encompass several southern sections of the Polish territories conquered in 1939 (around 18,000 km2), stretching from the area to the west of Kraków to the San river in the east.[16][17] At this time Germany had not yet directly annexed the Łódź area, and Łódź (rather than Kraków) served as the capital of the General Government.

In November 1940, Gauleiter Arthur Greiser of Reichsgau Wartheland argued that the counties of Tomaschow Mazowiecki and Petrikau should be transferred from the General Government's Radom district to his Gau. Hitler agreed, but since Frank refused to surrender the counties, the resolution of the border question was postponed until after the final victory.[18]

Upon hearing of the German plans to create a "Gau of the Goths" (Gotengau) in the Crimea and the Southern Ukraine after the start (June 1941) of Operation Barbarossa, Frank himself expressed his intention to turn the district under his control into a German province called the Vandalengau (Gau of the Vandals) in a speech he gave on 16 December 1941.[19][20]

When Frank unsuccessfully attempted to resign his position on 24 August 1942, Nazi Party Secretary Martin Bormann tried to advance a project to dissolve the General Government altogether and to partition its territory into a number of Reichsgaue, arguing that only this method could guarantee the territory's Germanization, while also claiming that Germany could economically exploit the area more effectively, particularly as a source of food.[21] He suggested separating the "more restful" population of the formerly Austrian territories (because this part of Poland had been under German-Austrian rule for a long period of time it was deemed more racially acceptable) from the rest of the Poles, and cordoning off the city of Warsaw as the center of "criminality" and underground resistance activity.[21]

Ludwig Fischer (governor of Warsaw from 1939 to 1945) opposed the proposed administrative streamlining resulting from these discussions. Fischer prepared his own project in his Main Office for Spatial Ordering (Hauptamt für Raumordnung) located in Warsaw.[21] He suggested[when?] the establishment of the three provinces Beskiden, Weichselland ("Vistula Land"), and Galizien (Galicia and Chełm) by dividing the Radom and Lublin districts between them. Weichselland was to have a "Polish character", Galizien a "Ukrainian" one, and the Beskiden-province to provide a German "admixture" (i.e. colonial settlement).[21] Further territorial planning carried out by this Warsaw-based organization under Major Dr. Ernst Zvanetti in a May 1943 study to demarcate the eastern border of "Central Europe" (i.e. the Greater German Reich) with the "Eastern European landmass" proposed an eastern German border along the "line Memel-Odessa".[22]

In this context Zvanetti's study proposed a re-ordering of the "Eastern Gaue" into three geopolitical blocs:[22]

- a western group comprising the Gaue Danzig-Westpreußen, Wartheland, and Schlesien (Silesia)

- a central group with the Gaue Ostpreußen (East Prussia), Südpreußen (South Prussia), Litzmannstadt (Łódź), and Beskidenland

- the eastern group with the Gau Südostpreußen (South-East Prussia) and including Wolhynien (Volhynia and the Lublin district), Galizien, and Podolien (Podolia).

Administration

The General Government was administered by a General-Governor (German: Generalgouverneur) aided by the Office of the General-Governor (German: Amt des Generalgouverneurs; changed on December 9, 1940 to the Government of the General Government, German: Regierung des Generalgouvernements). For the entire period of the General Government's existence there was only one General-Governor: Dr. Hans Frank. The NSDAP structure in General Government was Arbeitsbereich Generalgouvernement led by Frank.

The Office was headed by Chief of the Government (German: Regierung, lit. 'government'), Josef Bühler, who was also the State Secretary (German: Staatssekretär). From October 1939 to May 1940, Arthur Seyss-Inquart was the Deputy General-Governor. After his departure, Bühler served as Frank's deputy through January 1945. Several other individuals had powers to issue legislative decrees in addition to the General-Governor, most notably the Higher SS and Police Leader of the General Government (SS-Obergruppenführer Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger; from October 1943: SS-Obergruppenführer Wilhelm Koppe).

No government protectorate is anticipated for Poland, but a complete German administration. (...) Leadership layer of the population in Poland should be as far as possible, disposed of. The other lower layers of the population will receive no special schools, but are to be oppressed in some form. — Excerpt from the minutes of the first conference of Heads of the main police officers and commanders of operational groups led by Heydrich's deputy, SS-Brigadefuhrer Dr. Werner Best, Berlin 7 September 1939[23]

The General Government had no international recognition. The territories it administered were never either in whole or part intended as any future Polish state within a German-dominated Europe. According to the Nazi government the Polish state had effectively ceased to exist, in spite of the existence of a Polish government-in-exile.[24] The General Government had the character of a type of colonial state. It was not a Polish puppet government, as there were no Polish representatives above the local administration.

The government seat of the General Government was located in Kraków (German: Krakau; English: Cracow) rather than in Warsaw for security reasons. The official state language was German, although Polish continued in use by local government. Useful institutions of the old Polish state were retained for ease of administration. The Polish police, with no high-ranking Polish officers (they were arrested or demoted), was reorganised as the Blue Police and became subordinated to the Ordnungspolizei. The Polish educational system was similarly retained, but most higher institutions were closed. The Polish local administration was kept, subordinated to new German bosses. The Polish fiscal system, including the zloty currency, remained in use but with revenues going to the German state. A new bank was created; it issued new banknotes.

The Germans sought to play Ukrainians and Poles off against each other. Within ethnic Ukrainian areas annexed by Germany, beginning in October 1939, Ukrainian Committees were established with the purpose of representing the Ukrainian community to the German authorities and assisting the approximately 30,000 Ukrainian refugees who fled from Soviet-controlled territories. These committees also undertook cultural and economic activities that had been banned by the previous Polish government. Schools, choirs, reading societies and theaters were opened, and twenty Ukrainian churches that had been closed by the Polish government reopened. By March 1941, there were 808 Ukrainian educational societies with 46,000 members.

A Ukrainian publishing house and periodical press was set up in Cracow,[25] which – despite having to struggle with German censors and paper shortages – succeeded in publishing school textbooks, classics of Ukrainian literature, and the works of dissident Ukrainian writers from the Soviet Union. Krakivs'ki Visti was headed by Frank until the end of World War II and had as editor Michael Chomiak. It was "the leading legal newspaper" of the General Government and "attracted more (and better) contributors among whom were the most prominent Ukrainian cultural figures of the (early) 20th century."[26]

Ukrainian organizations within the General Government were able to negotiate the release of 85,000 Ukrainian prisoners of war from the German-Polish conflict (although they were unable to help Soviet POWs of Ukrainian ethnicity).[27]

After the war, the Polish Supreme National Tribunal declared that the government of the General Government was a criminal institution.

Judicial system

Other than summary German military tribunals, no courts operated in Poland between the German invasion and early 1940. At that time, the Polish court system was reinstated and made decisions in cases not concerning German interests, for which a parallel German court-system was established. The German system was given priority in cases of overlapping jurisdiction.

New laws were passed, discriminating against ethnic Poles and, in particular, the Jews. In 1941 a new criminal law was introduced, introducing many new crimes, and making the death penalty very common. The death penalty was introduced for, among other things:

- on October 31, 1939, for any acts against the German government

- on January 21, 1940, for economic speculation

- on February 20, 1940, for spreading sexually-transmitted diseases

- on July 31, 1940, for any Polish officers who did not register immediately with the German administration (to be taken to prisoner of war camps)

- on November 10, 1941, for giving any assistance to Jews

- on July 11, 1942, for farmers who failed to provide requested crops

- on July 24, 1943, for not joining the forced labor battalions (Baudienst) when requested

- on October 2, 1943, for impeding the German Reconstruction Plan

Policing

The police in the General Government was divided into:

- Ordnungspolizei (OrPo) (native German)

- the Blue Police (Polish under German control)

- Sicherheitspolizei (native German) composed of:

- Kriminalpolizei (German)

- Gestapo (German)

The most numerous OrPo battalions focused on traditional security roles as an occupying force. Some of them were directly involved in the pacification operations.[28] In the immediate aftermath of World War II, this latter role was obscured both by the lack of court evidence and by deliberate obfuscation, while most of the focus was on the better-known Einsatzgruppen ("Operational groups") who reported to RSHA led by Reinhard Heydrich.[29] On 6 May 1940 Gauleiter Hans Frank, stationed in occupied Kraków, established the Sonderdienst, based on similar SS formations called Selbstschutz operating in the Warthegau district of German-annexed western part of Poland since 1939.[30] Sonderdienst were made up of ethnic German Volksdeutsche who lived in Poland before the attack and joined the invading force thereafter. However, after the 1941 Operation Barbarossa they included also the Soviet prisoners of war who volunteered for special training, such as the "Trawniki men" (German: Trawnikimänner) deployed at all major killing sites of the "Final Solution". A lot of those men did not know German and required translation by their native commanders.[31][32]: 366 Ukrainian Auxiliary Police was formed in Distrikt Galizien in 1941, many policemen deserted in 1943 joining UPA.

The former Polish policemen, with no high-ranking Polish officers (who were arrested or demoted), were drafted to the Blue Police and became subordinated to the local Ordnungspolizei.

Some 3,000 men served with the Sonderdienst in the General Government, formally assigned to the head of the civil administration.[31] The existence of Sonderdienst constituted a grave danger for the non-Jewish Poles who attempted to help ghettoised Jews in the cities, as in the Mińsk Mazowiecki Ghetto among numerous others, because Christian Poles were executed under the charge of aiding Jews.[30]

A Forest Protection Service also existed, responsible for policing wooded areas in the General Government.[33]

A Bahnpolizei policed railroads.

The Germans used pre-war Polish prisons and organised new ones, like in Jan Chrystian Schuch Avenue police quarter in Warsaw and Under the Clock torture centre in Lublin.

German administration constructed a terror system to control Polish people enforcing reports of any illegal activities, e.g. hiding Roma, POWs, guerilla fighters, Jews. Germans designated hostages, terrorised local leaders, applied collective responsibility. German police used sting operations to find and kill rescuers of the Germans' quarries.[34]

Military occupation forces

Through the occupation Germany diverted a significant number of its military forces to keep control over Polish territories.

| Time period | Wehrmacht army | Police and SS

(includes German forces only) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| October 1939 | 550,000 | 80,000 | 630,000 |

| April 1940 | 400,000 | 70,000 | 470,000 |

| June 1941 | 2,000,000 (high number due to imminent attack on Soviet positions) | 50,000 | 2,050,000 |

| February 1942 | 300,000 | 50,000 | 350,000 |

| April 1943 | 450,000 | 60,000 | 510,000 |

| November 1943 | 550,000 | 70,000 | 620,000 |

| April 1944 | 500,000 | 70,000 | 570,000 |

| September 1944 | 1,000,000 (A small percentage took part in the suppression of the Warsaw Uprising) | 80,000 | 1,080,000 |

Nazi propaganda

The propaganda was directed by the Fachabteilung für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (FAVuP), since Spring 1941 Hauptabteilung Propaganda (HAP). Prasą kierował Dienststelle der Pressechef der Regierung des Generalgouvernements, a w Berlinie Der Bevollmächtige des Generalgouverneurs in Berlin.

Anti-semitic propaganda

Thousands of anti-Semitic posters were distributed in Warsaw.[36][37]

Political propaganda

Germans wanted Poles to obey orders.[38]

Polish language newspapers

- Nowy Kurier Warszawski

- Kurier Częstochowski

- Goniec Krakowski

- Dziennik Radomski

- Goniec Codzienny

- Ilustrowany Kurier Polski

- Gazeta Lwowska

- Fala

Cinemas

Propaganda newsreels of Die Deutsche Wochenschau (The German Weekly Review) preceded feature-film showings. Some feature films likewise contained Nazi propaganda. The Polish underground discouraged Poles from attending movies, advising them, in the words of the rhymed couplet, "Tylko świnie / siedzą w kinie" ("Only swine go to the movies").[39]

In occupied Poland, there was no Polish film industry. However, a few Poles collaborated with the Germans in making films such as the 1941 anti-Polish propaganda film Heimkehr (Homecoming). In that film, casting for minor parts played by Jewish and Polish actors was done by Igo Sym, who during the filming was shot in his Warsaw apartment by the Polish Union of Armed Struggle resistance movement; after the war, the Polish performers were sentenced for collaboration in an anti-Polish propaganda undertaking, with punishments ranging from official reprimand to imprisonment.[40]

Theaters

All Polish theaters were disbanded. A German theater Theater der Stadt Warschau was formed in Warsaw together with a German controlled Polish one Teatr Miasta Warszawy. There existed also one comedy theater Teatr Komedia and 14 small ones. The Juliusz Słowacki Theatre in Cracow was used by Germans.

Audio propaganda

Poles were not allowed to use radio sets. Any set was to be handed over to local administration by 25 January 1940. Ethnic Germans were obliged to register their sets.[41]

German authorities installed megaphones for propaganda purposes, called by Poles szczekaczki (from pol. szczekać "to bark").[42]

Public executions

Germans killed thousands of Poles, many of them civilian hostages, in Warsaw streets and locations around Warsaw (Warsaw ring), to terrorize the population – they shot or hanged them.[43][44] The executions were ordered mainly by Austrian Nazi Franz Kutschera, SS and Police Leader, from September 1943 until January 1944.

Urban planning and transportation network

Warsaw was to be reconstructed according to Pabst Plan. The governmental quarter was situated around the Piłsudski Square.

The capital of GG Kraków was reconstructed according to Generalbebauungsplan von Krakau by Hubert Ritter. Hans Frank rebuild his residence Wawel Castle. <[45] Dębniki (Kraków) was the planned Nazi administrative quarter.[46][47] German-only residential area was constructed near Park Krakowski.[48]

Germans constructed railroad line Łódź-Radom (partially in GG) and engine house in Radom.[49]

Administrative districts

For administrative purposes the General Government was subdivided into four districts (Distrikte). These were the Distrikt Warschau, the Distrikt Lublin, the Distrikt Radom, and the Distrikt Krakau. After the Operation Barbarossa against the Soviets in June 1941, East Galicia (part of Poland, annexed by the Ukrainian SSR on the basis of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact), was incorporated into the General Government and became its fifth district: Distrikt Galizien. The new German administrative units were much larger than those organized by the Polish government, reflecting the German lack of sufficient administrative personnel to staff smaller units.[50]

The five districts were further sub-divided into urban counties (Stadtkreise) and rural counties (Kreishauptmannschaften). Following a decree on September 15, 1941, the names of most of the major cities (and their respective counties) were renamed based on historical German data or given germanified versions of their Polish and Soviet names if none existed. At times the previous names remained the same as well (i.e. Radom). The districts and counties were as follows:

| Distrikt Warschau | |

| Stadtkreise | Warschau (Warsaw) |

| Kreishauptmannschaften | Garwolin, Grojec (Grójec), Lowitsch (Lowicz), Minsk (Mińsk Mazowiecki), Ostrau (Ostrów Mazowiecka), Siedlce, Skierniewice2, Sochaczew, Sokolow-Wengrow (Sokołów Podlaski-Węgrów), Warschau-Land |

| Distrikt Krakau | |

| Stadtkreis/ kreisfreie Stadt (since 1940) |

Krakau (Kraków) |

| Kreishauptmannschaften | Dembitz (Dębica), Jaroslau (Jarosław), Jassel (Jaslo), Krakau-Land, Krosno1, Meekow (Miechów), Neumarkt (Nowy Targ), Neu-Sandez (Nowy Sącz), Przemyśl1, Reichshof (Rzeszow), Sanok, Tarnau (Tarnów) |

| Distrikt Lublin | |

| Stadtkreise | Lublin |

| Kreishauptmannschaften | Biala-Podlaska (Biała Podlaska), Bilgoraj, Cholm (Chelm), Grubeschow (Hrubieszow), Janow Lubelski, Krasnystaw, Lublin-Land, Pulawy, Rehden (Radzyn), Zamosch/Himmlerstadt/Pflugstadt (Zamość) |

| Distrikt Radom | |

| Stadtkreise | Kielce, Radom, Tschenstochau (Częstochowa) |

| Kreishauptmannschaften | Busko (Busko-Zdrój), Jedrzejow, Kielce-Land, Konskie (Końskie), Opatau (Opatów), Petrikau (Piotrków Trybunalski), Radom-Land, Radomsko, Starachowitz (Starachowice), Tomaschow Mazowiecki (Tomaszów Mazowiecki) |

| Distrikt Galizien | |

| Stadtkreise | Lemberg (Lviv/Lwów) |

| Kreishauptmannschaften | Breschan (Brzeżany), Tschortkau (Czortków), Drohobycz, Kamionka-Strumilowa (Kamianka-Buzka), Kolomea (Kolomyia), Lemberg-Land, Rawa-Ruska (Rava-Ruska), Stanislau (Ivano-Frankivsk), Sambor (Sambir) Stryj, Tarnopol, Solotschiw (Zolochiv), Kallusch (Kalush) |

| 1, added after 1941. 2, removed after 1941. |

A change in the administrative structure was desired by Finance Minister Lutz von Krosigk, who for financial reasons wanted to see the five existing districts (Warsaw, Kraków, Radom, Lublin, and Galicia) reduced to three.[21] In March 1943 he announced the merger of the Kraków and Galicia districts, and the split of the Warsaw district between the Radom district and the Lublin district.[21] (The latter acquired a special status of "Germandom district", Deutschtumsdistrikt, as a "test run" of the Germanization according to the Generalplan Ost.[51]) The restructuring further involved the changing of Warsaw and Kraków into separate city-districts (Stadtdistrikte), with Warsaw under the direct control of the General Government. This decree was to go into effect on 1 April 1943 and was nominally accepted by Heinrich Himmler, but Martin Bormann opposed the move, as he simply wanted to see the region turned into Reichsgaue (Germany proper). Wilhelm Frick and Friedrich-Wilhelm Krüger were also skeptic about the usefulness of this reorganization, resulting in its abolition after subsequent discussions between Himmler and Frank.[21]

Demographics

The General Government was inhabited by 11.4 million people in December 1939. A year later the population increased to 12.1 million. In December 1940, 83.3% of the population were Poles, 11.2% Jews, 4.4% Ukrainians and Belarusians, 0.9% Germans, and 0.2% others.[52] About 860,000 Poles and Jews were resettled into the General Government after they were expelled from the territories 'annexed' by Nazi Germany. Offsetting this was the German genocidal campaign of liquidation of the Polish intelligentsia and other elements considered likely to resist. From 1941 disease and hunger also began to reduce the population.

Poles were also deported in large numbers to work as forced labor in Germany: eventually about a million were deported, of whom many died in Germany. In 1940 the population was segregated into different groups. Each group had different rights, food rations, allowed strips in the cities, public transportation and restricted restaurants. They were divided from the most privileged, to the least.[citation needed]

| Nationality | Daily food energy intake |

|---|---|

| Germans | 2,310 Cal (9,700 kJ) |

| Foreigners | 1,790 Cal (7,500 kJ) |

| Ukrainians | 930 Cal (3,900 kJ) |

| Poles | 654 Cal (2,740 kJ) |

| Jews | 184 Cal (770 kJ) |

- Germans from Germany (Reichdeutsche),

- Germans from outside, active ethnic Germans, Volksliste category 1 and 2 (see Volksdeutsche).

- Germans from outside, passive Germans and members of families (this group also included some ethnic Poles), Volksliste category 3 and 4,

- Ukrainians,

- Highlanders (Goralenvolk) – an attempt to split the Polish nation by using local collaborators

- Poles (partially exterminated),[citation needed]

- Romani people (eventually largely exterminated as a category),

- Jews (eventually largely exterminated as a category).

Economics

After the invasion of Poland in 1939, Jews over the age of 12 and Poles over the age of 14 living in the General Government were subject to forced labor.[24] Many Poles from other regions of Poland conquered by Germany were expelled to the General Government and the area was used as a slave labour pool from which men and women taken by force to work as laborers in factories and farms in Germany.[5] In 1942, all non-Germans living in the General Government were subject to forced labor.[54]

Parts of Warsaw and several towns (Wieluń, Sulejów, Frampol) were destroyed during the Polish-German war in September 1939. Poles weren't able to buy any construction materials to reconstruct their houses or businesses. They lost their savings and GG currency, nicknamed "Młynarki", was managed by German-controlled Bank Emisyjny w Polsce.

Former Polish state property was confiscated by the General Government (or by Nazi Germany in the annexed territories). Notable property of Polish individuals (ex. factories and large land estates) was often confiscated as well and managed by German "trusts" (German: Treuhänder). Jewish population was deported to the Ghettos, their dwelling and businesses were confiscated by the Germans, small businesses were sometimes passed to the Poles.[55] Farmers were required to provide large food contingents for the Germans, and there were plans for nationalization of all but the smallest estates.

German administration implemented a system of exploitation of Jewish and Polish people, which included high taxes.[56]

Food supply

While scholars debate whether from September 1939 to June 1941 the mass-starvation of the Jewish people of Europe was an attempt to conduct mass murder, it is agreed upon that this starvation did kill a large amount of this population.[57] There was a shift in the amount of resources that were being used by the Generalgouvernement from 1939 to 1940. For example, in 1939, seven million tons of coal were used but in 1940 this was reduced to four million tons of coal used by the Generalgouvernement. This shift was emblematic of the shortages in supplies, depriving the Jews and Poles of their only heating source. Although before the war, Poland exported mass quantities of food, in 1940 the Generalgouvernement was unable to supply enough food for the country, nonetheless exporting food supplies.[58] In December 1939, the Polish and Jewish reception committees, as well as the native local officials, all within the Generalgouvernement, were responsible for providing food and shelter to the Poles and Jews that evacuated. In the expulsion process, the help provided to the evacuated Poles and Jews by the Generalgouvernement was considered a weak branch of the overall process.[59] Throughout 1939, the Reichsbahn was responsible for many of the other important tasks including the deportations of Poles and Jews to concentration camps as well as the delivery of food and raw materials to different places.[60] In December 1940, 87,833 Poles and Jews were deported which added stress to different administrations which were now responsible for these deportees. During the deportations, people were forced to reside on the trains for days until a place was found for them to stay. Between the cold and lack of food, masses of deportees died due to transport deaths caused by malnutrition, cold, and moreover unlivable transportation conditions.[59]

The prices for food outside of ghettos and concentration camps had to be set at a reasonable price in order for them to align with the black market; setting prices at a reasonable rate would ensure that farmers did not sell their crops illegally. If the prices were set too high in cities there was a concern that workers would not be able to afford the food and protest the prices. Due to the price inflation which was occurring in the Generalgouvernement, many places relied on the barter system (exchanging goods for other goods instead of money). "Introducing rationing in September 1940, Marshal Petain insisted that ‘everyone must assume their share of common hardship.’"[61] There was clearly food instability not only in the ghettos, but also in cities, which caused everyone to be conscious about food rationing, and caused conditions for Jewish people to worsen. While workers in Norway and France protested the new rationing of food, Germany and the UK, where the citizens supported war efforts were more supportive of the rationing therefore it was more effective. Cases, where a country was being occupied, caused the citizens to be more hesitant about the rationing of food and it was overall not as effective.[62] In December, 1941 it was recognized by the Generalgouvernement that starving the Jewish people to death was an inexpensive and expedient solution. In August 1942, the required food shipments from the General Government to the Reich were increased and decided that the 1.2 million Jews that were not completing jobs that were "important to Germany" would no longer be given food.[63] The Nazis knew the effects of depriving the Jewish people of food, yet it continued; the ultimate revolt against the Jewish race was mass murder due to starvation. The Food and Agriculture Ministry administered the rations of food in concentration camps.[64] Each camp's administration got food from the open market and depots of the Waffen-SS (Standartenführer Tschentscher). Once the food arrived at a camp, it was up to the administration how to distribute it. The diet for the Jews in these camps was "watery turnip soup drunk from pots; it was supplemented by an evening meal of sawdust bread with some margarine, ‘smelly marmalade,’ or ‘putrid sausage.’ Between the two meals inmates attempted to lap a few drops of polluted water from the faucet in a wash barracks."[65]

Black market

During this environment of food scarcity Jews turned to the black market for any source of sustenance. The black market was important both in and outside of the ghettos from 1940 to 1944. Outside of the ghettos, the black market existed because rations were not high enough for the citizens to remain healthy. In the ghettos of eastern Europe in August 1941 the Jewish population recognized that if they were forced to remain in these ghettos they would eventually die of hunger. Many people that were in ghettos made trades with the outside world in order to stay alive.[61] Jewish people were forced to reside in ghettos, where the economy was isolated and there were large food shortages, which caused them to be seen as a source for cheap labor; many were given food that was purchased on the Aryan side of the wall in exchange for their labor. The isolation of the people forced into ghettos caused there to be a disconnect between the buyer and seller, which added in another player: the black market middleman. The black market middleman would make a profit by creating connections between sellers and buyers. While supply and demand was inelastic in these ghettos, the selling of this food on the blackmarket was extremely competitive, and beyond the reach of most Jews in ghettos.[66]

Resistance

Resistance to the German occupation began almost at once, although there is little terrain in Poland suitable for guerrilla operations. Several small army troops supported by volunteers fought till Spring 1940, e.g. under major Henryk Dobrzański, after which they ceased due to German executions of civilians as reprisals.

The main resistance force was the Home Army (in Polish: Armia Krajowa or AK), loyal to the Polish government in exile in London. It was formed mainly of the surviving remnants of the pre-War Polish Army, together with many volunteers. Other forces existed side-by-side, such as the communist People's Army (Armia Ludowa or AL) parallel to the PPR, organized and controlled by the Soviet Union. The AK was estimated between 200,000 and 600,000 men, while the AL was estimated between 14,000 and 60,000.

German repressions in 1942-43 caused the Zamość uprising.

In April 1943 the Germans began deporting the remaining Jews from the Warsaw Ghetto, provoking the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, April 19 to May. 16 That was the first armed uprising against the Germans in Poland, and prefigured the larger and longer Warsaw Uprising of 1944.[citation needed]

In July 1944, as the Soviet armed forces approached Warsaw, the government in exile called for an uprising in the city, so that they could return to a liberated Warsaw and try to prevent a Communist take-over. The AK, led by Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, launched the Warsaw Rising on August 1 in response both to their government and to Soviet and Allied promises of help. However Soviet help was never forthcoming, despite the Soviet army being only 18 miles (30 km) away, and Soviet denial of their airbases to British and American planes prevented any effective resupply or air support of the insurgents by the Western allies. They used distant Italian bases in their Warsaw airlift instead. After 63 days of fighting the leaders of the rising agreed a conditional surrender with the Wehrmacht. The 15,000 remaining Home Army soldiers were granted POW status (prior to the agreement, captured rebels were shot), and the remaining civilian population of 180,000 expelled.

Education

All universities in GG were disbanded, many Kraków professors imprisoned during the Sonderaktion Krakau.

Culture of Poland

Germans plundered Polish museums. Many of the pieces of art perished.[67] Germans burned a number of Warsaw libraries, including the National Library of Poland, destroying about 3.6 million volumes.[68]

German sport

Hans Frank was an avid chess player, so he organized General Government chess tournaments. Only Germans were allowed to perform in sporting events. About 80 football clubs played in four district divisions.[69]

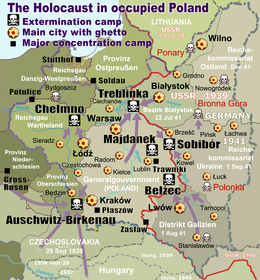

The Holocaust

During the Wannsee conference on January 20, 1942, the State Secretary of the General Government, SS-Brigadeführer Josef Bühler encouraged Heydrich to implement the "Final Solution". From his own point of view, as an administrative official, the problems in his district included an overdeveloped black market. He endorsed a remedy in solving the "Jewish question" as fast as possible. An additional point in favor of setting up the extermination facilities in his governorate was that there were no transportation problems there,[70] since all assets of the disbanded Polish State Railways (PKP) were being managed by Ostbahn, the Kraków-based Deutsche Reichsbahn branch of the Generaldirektion der Ostbahn ("General Directorate of Eastern Railways", Gedob). This made a network of death trains readily available to the SS-Totenkopfverbände.[71]

The newly drafted Operation Reinhard would be a major step in the systematic liquidation of the Jews in occupied Europe, beginning with those in the General Government. Within months, three top-secret camps were built and equipped with stationary gas chambers disguised as shower rooms, based on Action T4, solely to efficiently kill thousands of people each day. The Germans began the elimination of the Jewish population under the guise of "resettlement" in spring of 1942. The three Reinhard camps including Treblinka (the deadliest of them all) had transferable SS staff and almost identical design. The General Government was the location of four of the seven extermination camps of World War II in which the most extreme measures of the Holocaust were carried out, including closely located Majdanek concentration camp, Sobibor extermination camp and Belzec extermination camp. The genocide of undesired "races", chiefly millions of Jews from Poland and other countries, was carried out by gassing between 1942 and 1944.[72]

Punishments

- Hans Frank instituted a reign of terror against the civilian population[73] and became directly involved in the mass murder of Jews. At the Nuremberg trials, he was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity and was executed. His secretaries, Arthur Seyss-Inquart and Josef Bühler, were executed in Nuremberg and Poland, respectively.

- Ludwig Fischer was a governor of the Warsaw District. He was sentenced and hanged in Warsaw.

- Ernst Kundt was a governor of the Radom District. He was sentenced and hanged in Czechoslovakia.

Gallery

-

The wall of the Warsaw Ghetto being built under the orders of Dr. Ludwig

-

The Warsaw Ghetto (1940-1943)

-

Announcement by the Chief of SS and Police 5.09.1942—Death penalty for Poles offering any help to Jews

-

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, April 1943: Jews being held at gunpoint by SS troops (from a report written by Jürgen Stroop for Heinrich Himmler)

-

Warsaw Uprising: Polish soldiers in action, August 1, 1944

-

Polish civilians murdered by SS troops during the Warsaw Uprising, August 1944

-

Aerial view of the city of Warsaw, January 1945

-

Portrait of a Young Man by Raphael, stolen at the behest of Hans Frank in 1939 and never returned; one of over 40,000 works of art robbed from Polish collections

-

Polish hostages being blindfolded during preparations for their mass execution in Palmiry, 1940

-

A mass execution of Poles in Bochnia, December 18, 1939

-

The Warsaw Uprising, 1944

See also

- Areas annexed by Nazi Germany

- Chronicles of Terror

- Ernst Lerch

- German camps in occupied Poland during World War II

- Gestapo-NKVD Conferences

- Money transfers in the Generalgouvernement

- Postal communication in the General Government

- World War II evacuation and expulsion

- West Galicia

Notes

- a. ^ The RKF (also RKFDV) stands for the Reichskommissar für die Festigung des deutschen Volkstums, or the Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood, an office in Nazi Germany held by Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler. Meanwhile, the HTO stands for Haupttreuhandstelle Ost, or the Main Trustee Office for the East, a Nazi German predatory institution responsible for liquidating Polish and Jewish businesses across occupied Poland; and selling them off for profit mainly to the SS, or the German Volksdeutsche and war-profiteers if interested. The HTO was created and headed by Nazi potentate Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring.[74]

Citations

- ^ Diemut 2003, page 268. Archived 2023-03-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Diemut Majer (2003). "Non-Germans" Under the Third Reich: The Nazi Judicial and Administrative System in Germany and Occupied Eastern Europe with Special Regard to Occupied Poland, 1939–1945. JHU Press. pp. 236–246. ISBN 0801864933. Archived from the original on 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Piotr Eberhardt, Jan Owsinski (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis. M.E. Sharpe. p. 216. ISBN 9780765606655. Archived from the original on 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- ^ Ewelina Żebrowaka-Żolinas Polityka eksterminacyjna okupanta hitlerowskiego na Zamojszczyźnie Studia Iuridica Lublinensia 17, 213-229

- ^ a b c Keith Bullivant; Geoffrey J. Giles; Walter Pape (1999). Germany and Eastern Europe: Cultural Identities and Cultural Differences. Rodopi. p. 32.

- ^ Adam D. Rotfeld; Anatolij W. Torkunow (2010). White spots–black spots: difficult issues in Polish–Russian relations 1918–2008 [Białe plamy–czarne plamy: sprawy trudne w polsko-rosyjskich stosunkach 1918–2008] (in Polish). Polsko-Rosyjska Grupa do Spraw Trudnych, Polski Instytut Spraw Międzynarodowych. p. 378. ISBN 9788362453009. Archived from the original on 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2020-09-19..

- ^ Piotrowski, Stanisław (October 23, 1961). "Hans Frank's Diary". Państwowe Wydawn. Naukowe – via Google Books.

- ^ Liulevicius, Vejas G. (2000). War Land on the Eastern Front: Culture, Identity, and German Occupation in World War I. Cambridge University Press. p. 54. ISBN 9781139426640. Archived from the original on 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ "Erlaß des Führers und Reichskanzlers über die Gliederung und Verwaltung der Ostgebiete"

- ^ Majer (2003), p. 265.

- ^ Generalgouvernement Archived 2021-08-31 at the Wayback Machine Shoah Resource Center

- ^ a b Hitler, Adolf (2000). Bormann, Martin. ed. Hitler's Table Talk 1941-1944, 5 April 1942. trans. Cameron, Norman; Stevens, R.H. (3rd ed.). Enigma Books. ISBN 1-929631-05-7.

- ^ "Man to man...", Rada Ochrony Pamięci Walk i Męczeństwa, Warsaw 2011, p. 11. English version.

- ^ "Hitler's War; Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe". archive.ph. May 27, 2012. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2021.

- ^ Rich, Norman (1974). Hitler's War Aims: the Establishment of the New Order, p. 99. W. W. Norton & Company Inc., New York.

- ^ Burleigh, Michael (1988). "Germany Turns Eastwards: A Study of Ostforschung in the Third Reich". Cambridge University Press. p. 142. ISBN 9780521351201. Archived from the original on 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2022-03-14.

- ^ Madajczyk, Czesław (1988). Die okkupationspolitik Nazideutschlands in Polen 1939-1945, p. 31 (in German). Akademie-Verlag Berlin.

- ^ Catherine Epstein (2012), Model Nazi: Arthur Greiser and the Occupation of Western Poland, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0199646538, p. 139

- ^ Rich, p. 89.

- ^ NS-Archiv: Dokumente zum Nationalsozialismus. Diensttagebuch Hans Frank: 16.12.1941 - Regierungssitzung (in German). Retrieved 12 May 2011. [1] Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f g Madajczyk, pp. 102-103.

- ^ a b Wasser, Bruno (1993). Himmler's Raumplanung im Osten, pp. 82-83. Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel.

- ^ "Man to man...", Rada Ochrony Pamięci Walk i Męczeństwa, Warsaw 2011, English version

- ^ a b Majer (2003), p.302

- ^ Himka, John-Paul (1998). ""Krakivs'ki visti": An Overview". Harvard Ukrainian Studies. 22: 251–261. JSTOR 41036740. Archived from the original on 2022-05-29. Retrieved 2022-05-29.

- ^ Gyidel, Ernest (2019). "The Ukrainian Legal Press of the General Government: The Case of Krakivski Visti, 1940-1944". doi:10.7939/r3-7x8g-9w02.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Myroslav Yurkevich. (1986). Galician Ukrainians in German Military Formations and in the German Administration. In: Ukraine during World War II: history and its aftermath : a symposium (Yuri Boshyk, Roman Waschuk, Andriy Wynnyckyj, Eds.). Edmonton: University of Alberta, Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies Press pp. 73-74

- ^ Christopher R. Browning (1 May 2007). The Origins of the Final Solution. U of Nebraska Press. pp. 349, 361. ISBN 978-0803203921. Google eBook. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- ^ Hillberg, Raul, The Destruction of the European Jews, Holmes & Meir: NY, NY, 1985, pp 100–106.

- ^ a b The Erwin and Riva Baker Memorial Collection (2001). "Yad Vashem Studies". Yad Washem Studies on the European Jewish Catastrophe and Resistance. Wallstein Verlag: 57–58. ISSN 0084-3296. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ a b Browning, Christopher R. (1998) [1992]. "Arrival in Poland" (PDF file, direct download 7.91 MB complete). Ordinary Men: Reserve Police Battalion 101 and the Final Solution in Poland. Penguin Books. pp. 51, 98, 109, 124. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ^ David Bankir, ed. (2006). Police Auxiliaries for Operation Reinhard by Peter R. Black (Google Books). Enigma Books. pp. 331–348. ISBN 192963160X. Archived from the original on 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2013-06-02.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Benz, Wolfgang (1997). Enzyklopädie des Nationalsozialismus. Klett-Cotta. ISBN 3423330074.

- ^ Frydel, Tomasz (2018). "Judenjagd: Reassessing the Role of Ordinary Poles as Perpetrators in the Holocaust". In Williams, Timothy; Buckley-Zistel, Susanne (eds.). Perpetrators and Perpetration of Mass Violence: Action, Motivations and Dynamics. London: Routledge. pp. 187–203. Archived from the original on 2022-03-14. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ^ Czesław Madajczyk. Polityka III Rzeszy w okupowanej Polsce p.242 volume 1, Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa, 1970

- ^ "Defining Enemy, Holocaust Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 2018-05-24. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ "Grabowski, Antisemitic propaganda". Archived from the original on 2018-05-24. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ "Eksploatacja wsi 1939-1945 - fotogaleria - Fotogaleria - Martyrologia Wsi Polskich". Archived from the original on 2018-06-18. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ^ Marek Haltof. "Polish National Cinema". Archived from the original on 2018-05-24. Retrieved 2018-05-24.

- ^ Januszewski, Bartosz (13 September 2017). "Kino i teatr pod okupacją. Polskie środowisko filmowe i teatralne w czasie II wojny światowej" (PDF) (in Polish). Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ http://www.historiaradia.neostrada.pl/Okupacja%201939-44.html Archived 2018-08-03 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL]

- ^ http://www.polska1918-89.pl/pdf/gadzinowki-i-szczekaczki.-,5383.pdf Archived 2018-06-27 at the Wayback Machine [bare URL PDF]

- ^ "Execution Sites". Archived from the original on 2018-06-28. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- ^ "1944: Twenty-two or more Poles | Executed Today". February 11, 2009. Archived from the original on June 28, 2018.

- ^ "Hans Frank przebudowuje Wawel". 2019-04-17. Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ^ "Hitlerowskie wizje Krakowa". Archived from the original on 2019-05-14. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ "Wyborcza.pl". Archived from the original on 2019-05-14. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ "Niemieckie osiedle mieszkaniowe koło Parku Krakowskiego". 2017-04-13. Archived from the original on 2019-05-14. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- ^ "Poniemiecka parowozownia na sprzedaż. Jednak jeszcze nie teraz :: Radom24.pl :: Portal Radomia i regionu". Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2019-05-15.

- ^ Rich (1974), p. 86.

- ^ Frank Uekötter, "The Green and the Brown: A History of Conservation in Nazi Germany", 2006, ISBN 0521612772, pp. 158-159

- ^ Włodzimierz Bonusiak. Polska podczas II wojny światowej (Poland during II World War). Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Rzeszowskiego. 2003. p.68.

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, p.226, volume 2.

- ^ Majer (2003), p.303

- ^ "Treuhänder - Glossary - Virtual Shtetl". Archived from the original on 2016-08-06. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ^ Götz Aly, Hitler's Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State

- ^ Sinnreich, Helene Julia (May 2004). "The Supply and Distribution of Food to the Łódź Ghetto- A Case Study in Nazi Jewish Policy, 1939 -1945". ProQuest: 56. ProQuest 305208240.

- ^ Gross, Jan Tomasz (1979). Polish Society Under German Occupation: The Generalgouvernement: 1939-1944. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 92. ISBN 0691093814.

- ^ a b Rutherford, Phillip (2003). ""Absolute Organizational Deficiency": The 1.Nahplan of December 1939 (Logistics, Limitations, and Lessons)". Central European History. 36 (2): 254. doi:10.1163/156916103770866130. ISSN 0008-9389. JSTOR 4547300. S2CID 145343274.

- ^ Rutherford, Phillip (2003). ""Absolute Organizational Deficiency": The 1.Nahplan of December 1939 (Logistics, Limitations, and Lessons)". Central European History. 36 (2): 248. doi:10.1163/156916103770866130. JSTOR 4547300. S2CID 145343274.

- ^ a b Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe. London, UK: The Penguin Press. p. 279. ISBN 9780713996814.

- ^ Mazower, Mark (2008). Hitler's Empire: How the Nazis Ruled Europe. London, UK: The Penguin Press. pp. 277–279. ISBN 9780713996814.

- ^ Gross, Jan Tomasz (1979). Polish Society Under German Occupation: The Generalgouvernement: 1939-1944. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 102. ISBN 0691093814.

- ^ Sinnreich, Helene Julia (May 2004). "The Supply and Distribution of Food to the Łódź Ghetto- A Case Study in Nazi Jewish Policy, 1939 -1945". ProQuest: vii. ProQuest 305208240.

- ^ Hilberg, Raul (2003). The Destruction of the European Jews. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. pp. 581–582.

- ^ Gross, Jan Tomasz (1979). Polish Society Under German Occupation: The Generalgouvernement: 1939-1944. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 0691093814.

- ^ "22 Precious Works of Art That Vanished During World War II". Archived from the original on 2019-05-17. Retrieved 2019-05-17.

- ^ various authors; Tomasz Balcerzak; Lech Kaczyński (2004). Tomasz Balcerzak (ed.). Pro memoria: Warszawskie biblioteki naukowe w latach okupacji 1939-1945. transl. Philip Earl Steele. Warsaw: Biblioteka Narodowa. p. 4.

- ^ "Polsko-niemiecka historia piłki, czyli powrót do przeszłości". 2015-12-27. Archived from the original on 2018-05-25. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- ^ Adolf Eichmann. "The Wannsee Conference Protocol". Dan Rogers (translator). University of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ Jerzy Wasilewski (2014). "25 września. Wcielenie kolei polskich na Śląsku, w Wielkopolsce i na Pomorzu do niemieckich kolei państwowych Deutsche Reichsbahn". Polskie Koleje Państwowe PKP. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ Arad, Yitzhak (1999) [1987]. Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. p. 37. ISBN 0253213053. ASIN 0253213053 – via Internet Archive.

Belzec.

- ^ "Holocaust Encyclopedia: Hans Frank". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 7 May 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- ^ Mirosław Sikora (16 September 2009), "Aktion Saybusch" na Żywiecczyźnie. Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine Regional branch of the Institute of National Remembrance IPN Katowice. Reprint. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

References

- Kochanski, Halik. The Eagle Unbowed: Poland and the Poles in the Second World War (2012)

- Mędykowski, Witold Wojciech. Macht Arbeit Frei?: German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939-1943 (2018)

- Generalgouvernement on the Yad Vashem website

- Testimony of Frank at Nuremberg, examined by his defense attorney, Dr. Alfred Seidl, 4/18/1946.

- General Government NAZI occupied Poland, the CIH World War II Pages. Retrieved 24 August 2015.

- Collections of civilian testimonies from Nazi-occupied Poland in testimony database "Chronicles of Terror"

Further reading

- Mędykowski, Witold W. (2018). Macht Arbeit Frei?: German Economic Policy and Forced Labor of Jews in the General Government, 1939-1943. Jews of Poland. Boston: Academic Studies Press. ISBN 9781618119568. Archived from the original (pdf) on 2019-02-01. Retrieved 2019-02-01.

50°03′17″N 19°56′12″E / 50.05472°N 19.93667°E

Lua error in Module:Navbox at line 192: attempt to concatenate field 'argHash' (a nil value).

- General Government

- German occupation of Poland during World War II

- Nazi colonies in Eastern Europe

- World War II occupied territories

- Ukraine in World War II

- Jewish Polish history

- Jewish Ukrainian history

- The Holocaust in Poland

- Poland in World War II

- History of Ukraine (1918–1991)

- States and territories established in 1939

- States and territories disestablished in 1945

- 1939 establishments in Poland

- 1945 disestablishments in Poland

- 1939 establishments in Ukraine

- 1945 disestablishments in Ukraine

- People from wartime administrations in Poland (1939–1947)