Republika Srpska (1992–1995)

Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992)Српска Република Босна и ХерцеговинаSrpska Republika Bosna i Hercegovina Republika Srpska (1992–1995) Република СрпскаRepublika Srpska | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992–1995 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: Боже правде Bože Pravde "God of Justice" | |||||||||||||||||||

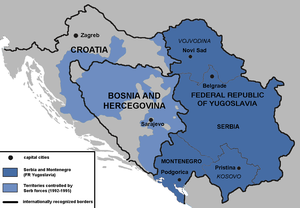

Approximate territory under the control of Republika Srpska at the time of Vance-Owen Plan in May 1993 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized client state of Yugoslavia/Serbia[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Pale | ||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Serbian | ||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Serbian Orthodox | ||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | ||||||||||||||||||

| President | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1992–1995 | Radovan Karadžić | ||||||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||||||||

• 1992–1993 | Branko Đerić | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1993–1994 | Vladimir Lukić | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1994–1995 | Dušan Kozić | ||||||||||||||||||

• 1995 | Rajko Kasagić | ||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | National Assembly | ||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Breakup of Yugoslavia | ||||||||||||||||||

| 9 January 1992 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 28 February 1992 | |||||||||||||||||||

• Renamed | 12 August 1992 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 6 April 1992 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 14 December 1995 | |||||||||||||||||||

| Currency |

| ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Bosnia and Herzegovina | ||||||||||||||||||

Republika Srpska (RS; Serbian Cyrillic: Република Српска, lit. 'Serbian Republic', pronounced [repǔblika sr̩̂pskaː] ⓘ) was a self-proclaimed proto-statelet in Southeastern Europe under the control of the Army of Republika Srpska during the Bosnian War. It claimed to be a sovereign state, though this claim was only partially recognized by the Bosnian government (whose territory the RS was recognized as nominally being a part of) in the Geneva agreement, the United Nations, and FR Yugoslavia. For the first six months of its existence, it was known as the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Serbian: Српска Република Босна и Херцеговина / Srpska Republika Bosna i Hercegovina).

After 1995, the Republika Srpska was recognized as one of the two political entities composing Bosnia and Herzegovina. The borders of the post-1995 RS are, with a few negotiated modifications, based on the front lines and situation on the ground at the time of the Dayton Agreement. As such, the entity is primarily a result of the Bosnian War without any direct historical precedent. Its territory encompasses a number of Bosnia and Herzegovina's numerous historical geographic regions, but (due to the above-mentioned nature of the inter-entity boundary line) it contains very few of them in entirety. Likewise, various political units existed within Republika Srpska's territory in the past but very few existed entirely within the region.

History

[edit]Creation

[edit]

Representatives of main political and national organizations and institutions of Serb people in Bosnia and Herzegovina met on 13 October 1990 in Banja Luka and created "Serbian National Council of Bosnia and Herzegovina" as a coordinative and representative political body.[2] The governing coalition of Bosnia and Herzegovina collapsed after the parliament of the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina in Sarajevo passed a 'memorandum on sovereignty' on 15 October 1991 that was opposed by Bosnian Serb members.[3] After the walkout of Bosnian Serb representatives, the memorandum was adopted. It declared the republic a sovereign and independent state and rejected "any constitutional solutions for a future Yugoslav community which would not include both Croatia and Serbia".[4] In response, on 24 October 1991 the Serb Democratic Party (SDS) formed the Assembly of the Serb People of Bosnia and Herzegovina as the representative body of Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina and declared that the Serb people wished to remain in Yugoslavia.[5] Bosnian Serbs claimed that this was a necessary step since the Constitution of Bosnia and Herzegovina, at that time, defined that no major changes were to be granted short of a unanimous agreement on all three sides. The Party of Democratic Action (SDA), led by Alija Izetbegović, was determined to pursue independence and was supported by Europe and the U.S.[6] The SDS made it clear that if independence was declared, Serbs would secede as it was their right to exercise self-determination.[6]

In the fall of 1991, the SDS organised the creation of "Serb Autonomous Regions" (SAOs) in Bosnia where Serbs formed the majority consisting of the SAO East and Old Herzegovina, SAO Bosnian Krajina, SAO Romanija and SAO North-Eastern Bosnia. They comprised nearly one-third of Bosnia's municipality and about 45% of its ethnic Serb population.[7] Similar steps were taken by the Bosnian Croats.[8] A Bosnian Serb referendum that asked citizens whether they wanted to remain within Yugoslavia was held on 9 and 10 November 1991, passing in favor of staying within Yugoslavia.[7] The parliamentary government of Bosnia and Herzegovina (with a clear Bosniak and Croat majority) asserted that this plebiscite was illegal, but the Bosnian Serb assembly acknowledged its results. On 21 November 1991, the Assembly proclaimed that all those municipalities, local communities, and populated places in which over 50% of the people of Serbian nationality had voted in favor of remaining in a joint Yugoslav state, would be territory of the federal Yugoslav state.[9]

On 9 January 1992, the Bosnian Serb assembly adopted a declaration on the Proclamation of the Republic of the Serb people of Bosnia and Herzegovina.[10] On 28 February 1992, the constitution of the Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Serbian: Srpska Republika Bosna i Hercegovina / Српска Република Босна и Херцеговина) was adopted and declared that the state's territory included Serb autonomous regions, municipalities, and other Serbian ethnic entities in Bosnia and Herzegovina (including regions described as "places in which the Serbian people remained in the minority due to the genocide conducted against them during World War II"), and it was declared to be a part of the federal Yugoslav state.[11]

From 29 February to 2 March 1992, Bosnia and Herzegovina held a referendum on independence that was boycotted by Bosnian Serbs, in which 99.7% voted in favor.[12] On 6 April 1992, the European Union formally recognized the independence of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The Serbian Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina declared its independence on 7 April 1992.[10] On 12 August 1992, the reference to Bosnia and Herzegovina was dropped from the name, and it became simply Republika Srpska.[13]

During the breakup of Yugoslavia, Srpska's President Radovan Karadžić declared that he did not want Srpska to be in a federation alongside Serbia in Yugoslavia, but that Srpska should be directly incorporated into Serbia.[14]

Bosnian War

[edit]

On 12 May 1992, at a session of the Bosnian Serb assembly, Radovan Karadžić announced the six "strategic objectives" of the Serb people in Bosnia and Herzegovina:[15]

- Establish state borders separating the Serb people from the other two ethnic communities.

- Set up a corridor between Semberija and Krajina.

- Establish a corridor in the Drina river valley, that is, eliminate the Drina as a border separating Serbian states.

- Establish a border on the Una and Neretva rivers.

- Divide the city of Sarajevo into Serb and Bosniak parts and establish effective state authorities in both parts.

- Ensure access to the sea for Republika Srpska.

At the same session, the Bosnian Serb assembly voted to create the Army of the Republika Srpska (VRS; Vojska Republike Srpske), and appointed Ratko Mladić, the commander of the Second Military District of the Yugoslav federal army, as commander of the VRS Main Staff. At the end of May 1992, after the withdrawal of Yugoslav forces from Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Second Military District was essentially transformed into the Main Staff of the VRS. The new army immediately set out to achieve by military means the six "strategic objectives" of the Serbian people in Bosnia and Herzegovina (the goals of which were reaffirmed by an operational directive issued by General Mladić on 19 November 1992).[15]

The VRS expanded and defended the borders[16] of Republika Srpska during the Bosnian War. By 1993 Republika Srpska controlled about 70% of the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina with final agreement (Dayton Agreement) in 1995 appropriating to Republika Srpska control over 49% of the territory.[17]

In 1993 and 1994, the authorities of Republika Srpska ventured to create the United Serb Republic.

War crimes

[edit]Since the beginning of the war, the VRS (Army of Republika Srpska) and the political leadership of Republika Srpska have been accused of war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, ethnic cleansing of the non-Serb population, creation and running of detention camps (variably also referred to as concentration camps and prisoner camps), and the destruction of the Bosnian-Herzegovinian cultural and historical heritage. The gravest of those offenses were the Srebrenica Genocide in 1995, where nearly 8,000 Bosniak men and boys were systematically executed by the VRS, and the long military siege of Sarajevo that resulted in 12,000 civilian casualties.

A highly classified report by the CIA which was leaked by the press claimed that Bosnian Serbs were the first to commit atrocities, carried out 90 percent of war crimes, and were the only party who systematically attempted to "eliminate all traces of other ethnic groups from their territory".[18][19][20] Ethnic cleansing dramatically changed the demographic picture of Republika Srpska and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Many Republika Srpska officials were also indicted for creation and running of detention camps, in particular Omarska, Manjaca, Keraterm, Uzamnica and Trnopolje where thousands of detainees were held. Duško Tadić, former SDS leader in Kozarac and a former member of the paramilitary forces supporting the attack on the district of Prijedor, was found guilty by the ICTY of crimes against humanity, grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions, and violations of the customs of war at Omarska, Trnopolje and Keraterm detention camps.[21] In Omarska region around 500 deaths have been confirmed associated with these detention facilities.

According to the findings of the State Commission for the Documentation of War Crimes on the Territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina, 68.67% or 789 congregational mosques were either destroyed or damaged during the Bosnian War by the VRS and other unidentified individuals from the Republika Srpska.[22] The majority of destroyed mosques had been classified as Bosnian-Herzegovinian national monuments; some, mostly built between the 15th and 17th centuries, were listed with UNESCO as world heritage monuments. Many Catholic churches in the same territory were also destroyed or damaged especially during 1995.

In addition to sacred monuments many secular monuments were also heavily damaged or destroyed by VRS forces such as the National Library in Sarajevo. The Library was set ablaze by shelling from VRS positions around Sarajevo during the siege in 1992.

While the individuals responsible for destruction of national heritage have not yet been found, or indicted, it has been widely reported by international human rights agencies that the "Bosnian Serb authorities issued orders or organized or condoned efforts to destroy Bosniak and Croatian cultural and religious institutions".[23] In other cases such as the Ferhadija Mosque case (Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Republika Srpska) it was found that: "Banja Luka authorities had actively engaged in, or had at least passively tolerated, discrimination against Muslims on the basis of their religious and ethnic origin." and that "[...] the Serb government [Republika Srpska], had failed to meet its obligation under the Human Rights Agreement to respect and secure the right to freedom of religion without discrimination."[24] A local magistrate ruled that the authorities of the Bosnian Serb controlled town Banja Luka must pay $42 million to its Islamic community for 16 local mosques destroyed during the 1992–1995 Bosnian war.[25]

The prosecution proved that genocide was committed in Srebrenica and that General Radislav Krstić, among others, was personally responsible for that.

In 1993, the United Nations Security Council created the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) at The Hague for the purpose of bringing to justice persons allegedly responsible for serious violations of international humanitarian law in the territory of the former Yugoslavia since 1991. On 24 July 1995, the Hague Tribunal indicted Radovan Karadžić[27] and Ratko Mladić[15] on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity; on 14 November 1995, both men were indicted again on charges specific to the Srebrenica massacre. On 2 August 2001, the Hague Tribunal found General-Major Radislav Krstić, the commander of the VRS Drina Corps at the time responsible for the Srebrenica massacre, guilty of genocide.[27] Many other political leaders of Republika Srpska and VRS officers, have been indicted, tried, and convicted by the Hague Tribunal for war crimes and crimes against humanity committed during the 1992–1995 war in Bosnia.

In 2006, a list of nearly 28,000 individuals who, according to the Republika Srpska authorities, were involved in Srebrenica massacre alone was released; 892 of those allegedly responsible still hold the positions in the local government of Republika Srpska.[28] The arrests and trials of all war crime suspects are ongoing and their trials are planned to be held at the newly established Bosnian Herzegovinian Tribunal for the War Crimes. The trials of all suspected war criminals are expected to last for years to come.

Two days after international judges in The Hague ruled that Bosnian Serb forces had committed genocide in the killing of nearly 8,000 Muslims in Srebrenica in 1995. "The government of the Republika Srpska expressed its deepest regret for the crimes committed against non-Serbs and condemned all persons who took part in these crimes during the civil war in Bosnia" the statement said.[29]

Controversy

[edit]

Between May 1992 to January 1993, Bosniak forces under the leadership of Naser Orić attacked and destroyed scores of Serbian villages in the areas around Srebrenica. Evidence indicated that Serbs had been tortured and mutilated and others were burned alive when their houses were torched.[30] While it is established that Serbs suffered a number of casualties, their exact nature and numbers have been a source of controversy. The ultra-nationalist Serbian Radical Party has used these casualties for political purposes and as a means of diminishing the July 1995 crime committed against Bosniaks.[31] In 2005, The ICTY Office of the Prosecutor (OTP) noted that the number of Serb deaths in the region between May 1992 and March 1995 alleged by the Serbian authorities had increased from 1,400 to 3,500, a figure the OTP stated "[does] not reflect the reality", particularly the labeling of all casualties as "victims".[32] Studies show a high number of military casualties compared to civilian. The Sarajevo-based Research and Documentation Centre, a non-partisan institution, found that Serb casualties in the Bratunac municipality amounted to 119 civilians and 424 soldiers.[33] Some Serb sources maintain that casualties and losses during the period prior to the creation of the safe area gave rise to Serb demands for revenge against the Bosniaks based in Srebrenica. The ARBiH raids are presented as a key motivating factor for the July 1995 genocide.[34][35]

Army

[edit]The Army of the Republika Srpska (VRS) was founded on 12 May 1992 from the remnants of the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia from which Bosnia and Herzegovina had seceded earlier in 1992. When the Bosnian War erupted, the JNA formally discharged 80,000 Bosnian Serb troops. These troops, who were allowed to keep their heavy weapons, formed the backbone of the newly formed Army of the Republika Srpska.[36] There was also volunteers from Christian Orthodox countries. According to the ICTY, volunteers from Russia, Greece, and Romania fighting for the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) numbered between at least 500 to more than 1,500. Other estimate vary depending on sources, with some estimate from 529 and 614, other claim that number is well over 1,000 volunteers from Orthodox countries.[37] The supreme commander of the VRS was General Ratko Mladić. The VRS was organized into six geographically based corps.[38]

Economy

[edit]During the first two years of the war, Republika Srpska issued its own unique currency, the Republika Srpska dinar.[39] This currency was pegged to the Yugoslav dinar.[40] The Serb, Croat and Bosniak authorities all issued their own dinar currencies in the territories they controlled, printing large excess of money to finance their operations which resulted in high inflation.[41] The electronic payment system of Republika Srpska was integrated with the system of the Republic of Yugoslavia and Republika Srpska's National Bank saw itself as a branch of the Central Yugoslav Bank in Belgrade. The inflation experienced in Yugoslavia thus transferred to Republika Srpska causing hyperinflation and eventual collapse of its currency in 1994.[40] The National Bank of Yugoslavia (CBCG) also cut the Republika Srpska off, preventing it from redeeming its currency there and refusing to send more due to the CBCG's lack of foreign exchange assets.[42] Afterwards, Republika Srpska did not form its own currency and continued to use the Yugoslav one. In 1999, it adopted the convertible mark.[41]

Unemployment was a major problem which the war exacerbated. Nearly a third of the workforce was in industry, mining and energy and the pre-war non-agricultural unemployment rate was at 27%. In 1996, UNESCO estimated that the unemployment rate in Republika Srpska was 90%.[43] Following the signing of the Dayton Accords, recovery in Republika Srpska was slower than in the Federation, as it received only 2-3% of the Western Aid to Bosnia. There was zero growth. Inflation was at 30%. Non-agricultural unemployment was at 60%, the average wage at 60 Deutsche Marks and pension at 33 DM. Government expenditures were also drastically higher than in the Federation.[44][45]

Education

[edit]In 1992-1993, the curriculum of Republika Srpska underwent changes to conform more towards Serbia. Adaptations were made in the subjects of history, social sciences, history and geography while religion became compulsory.[46] In 1996, education was 6.1% of the Republika Srpska budget.[47] There were 90 secondary schools and 54 vocational schools. The University Act of 23 July 1993 propelled the legal formation of post-secondary education in Republika Srpska, governing two Universities: The University of Banja Luka and University of East Sarajevo. UNESCO estimated there were more than 10,000 University students in 1996.[48]

Aftermath

[edit]

In November 1995 the Dayton Agreement was signed by presidents of Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia that ended the Bosnian war. The Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (FBiH) was defined as one of the two entities of Bosnia and Herzegovina and comprised 51% of the territory. The Republika Srpska (RS) comprised the other 49% with Banja Luka serving as its capital.[49]

Refugees

[edit]As a result of Operation Storm, nearly 200,000 Serbs fled from Croatia and a large portion of them found refuge in Bosnia, especially in Republika Srpska.

After the signing of the Dayton agreement, more than 60,000 Serbs left Sarajevo and other parts of Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina whether by choice or force, particularly after the territorial provisions were enforced to comply with the agreement.[50]

Reforms

[edit]After the war numerous laws were passed by the Republika Srpska authorities under the auspices of the international community acting through the Office of the High Representative (OHR). Many laws dealt with the issues and consequences of the war and served to repair some of the problems created such as annulments of ill-fate contracts that required non-Serbs to "voluntarily" turn over their properties to the Republika Srpska including real-estates and businesses taken during the war.

Many constitutional changes were also made to change the social character of the Republika Srpska from mono-ethnic to a multi-ethnic entity and thus including Bosniaks and Croats as constituent people of Republika Srpska. Some of the names of the cities that were changed during the war by the authorities of Republika Srpska were changed back. Most of the changes were done as to retract effects of ethnic cleansing and allow refugees to return, but also as a response to numerous reports of human rights abuses that were taking place in the entity.[51]

However, most of the changes had very little effect on a return of more than a million refugees. Intimidation of returnees were quite common and occasionally escalated into violent riots as in the case of Ferhadija mosque riots in Banja Luka in 2001.[52][53][54][55] Consequently, the views concerning Republika Srpska are different among various ethnic groups within the Bosnia and Herzegovina. For Serbs, the Republika Srpska is a guarantee for their survival and existence as a people within these territories. On the other hand, for some ethnic Bosniaks, who were ethnically cleansed from Republika Srpska, the creation, existence, name and insignia of this entity remains a matter of controversy.

Report on Srebrenica

[edit]In September 2002, the Republika Srpska Office of Relations with the ICTY issued the "Report about Case Srebrenica". The document, authored by Darko Trifunović, was endorsed by many leading Bosnian Serb politicians. It concluded that 1,800 Bosnian Muslim soldiers died during fighting and a further 100 more died as a result of exhaustion. "The number of Muslim soldiers killed by Bosnian Serbs out of personal revenge or lack of knowledge of international law is probably about 100...It is important to uncover the names of the perpetrators in order to accurately and unequivocally establish whether or not these were isolated instances."[56] The International Crisis Group and the United Nations condemned the manipulation of their statements in this report.[57]

In 2004, the international community's High Representative Paddy Ashdown had the Government of Republika Srpska form a committee to investigate the events. The committee released a report in October 2004 with 8,731 confirmed names of missing and dead persons from Srebrenica: 7,793 between 10 and 19 July 1995 and further 938 people afterwards.[58][59]

The findings of the committee remain generally disputed by Serb nationalists, who claim it was heavily pressured by the High Representative, given that an earlier RS government report which exonerated the Serbs was dismissed. Nevertheless, Dragan Čavić, the president of Republika Srpska, acknowledged in a televised address that Serb forces killed several thousand civilians in violation of the international law, and asserted that Srebrenica was a dark chapter in Serb history.[60]

On 10 November 2004, the government of Republika Srpska issued an official apology. The statement came after a government review of the Srebrenica committee's report. "The report makes it clear that enormous crimes were committed in the area of Srebrenica in July 1995. The Bosnian Serb Government shares the pain of the families of the Srebrenica victims, is truly sorry and apologises for the tragedy." the Bosnian Serb government said.[61]

In April 2010, a resolution condemning the crimes committed in Srebrenica was rejected by representatives of parties from Republika Srpska.[62]

In April 2010, Milorad Dodik, the prime minister of Republika Srpska, initiated a revision of the 2004 report saying that the numbers of killed were exaggerated and the report was manipulated by a former peace envoy.[63] The Office of the High Representative responded and stated that: "The Republika Srpska government should reconsider its conclusions and align itself with the facts and legal requirements and act accordingly, rather than inflicting emotional distress on the survivors, torture history and denigrate the public image of the country".[64]

References

[edit]- ^ Sara Darehshori, Human Rights Watch (Organization). Weighing the Evidence: Lessons from the Slobodan Milosevic Trial, Volume 18 (2006), Human Rights Watch, p. 19.

- ^ Daily Report: East Europe. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. 1990. pp. 58–59.

- ^ Egbert, Jahn (2008). Nationalism in Late and Post-Communist Europe: The Failed Nationalism of the Multinational and Partial National States, Volume 1. Nomos Verlag. p. 293. ISBN 9783832939687.

- ^ Trbovich 2008, pp. 220–221.

- ^ Trbovich 2008, p. 224.

- ^ a b Burg & Shoup 1999, p. 103.

- ^ a b Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990-1995, Volume 1. Central Intelligence Agency. 2002. p. 123. ISBN 9780160664724.

- ^ Burg & Shoup 1999, p. 74.

- ^ Troebst, Stefan; Daftary, Farimah, eds. (2004). Radical Ethnic Movements in Contemporary Europe. Berghahn Books. p. 123. ISBN 9781571816955.

- ^ a b Trbovich 2008, p. 228.

- ^ Lauterpacht, E.; Greenwood, C.J.; Oppenheimer, A. G., eds. (1998). International Law Reports, Volume 108. Cambridge University Press. p. 108. ISBN 9780521580700.

- ^ Pickering, Paula M. (2018). Peacebuilding in the Balkans: The View from the Ground Floor. Cornell University Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780801463464.

- ^ Dahlhoff, Guenther (2012). International Court of Justice, Digest of Judgments and Advisory Opinions, Canon and Case Law 1946 - 2012 (2 Vols.). Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 938. ISBN 9789004230637.

- ^ Daily report: East Europe, Issues 191–210. Front Cover United States. Foreign Broadcast Information Service. Pp. 38. (A recorded conversation between Branko Kostic and Srpska's President Radovan Karadzic, Kostic asks whether Karadzic wants Srpska to be an autonomous federal unit in federation with Serbia, Karadzic responds by saying that he wants complete unification of Srpska with Serbia as a unitary state similar to France.)

- ^ a b c "Prosecutor v. Ratko Mladic – Amended Indictment" (PDF). United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 2 August 2001.

- ^ Breakup of Yugoslavia and Yugoslav Wars, retrieved 3 December 2022

- ^ "NOTE ON THE MAIN ELEMENTS OF THE DAYTON AGREEMENT FOR BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA" (PDF). European Parliament. 28 September 2005.

- ^ Kressel, Neil Jeffrey (2002). Mass Hate: Global Rise to Genocide and Terror. Westview Press. p. 15. ISBN 0-8133-3951-0.

- ^ Cohen, Roger (9 March 1995). "C.I.A. Report on Bosnia Blames Serbs for 90% of the War Crimes". The New York Times.

- ^ Thomas Cushman, Thomas Cushman (1996). This Time We Knew: Western Responses to Genocide in Bosnia. New York University Press. p. 94. ISBN 0-8147-1535-4.

- ^ "Prosecutor v. Duško Tadić – Judgement" (PDF). International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 14 July 1997.

- ^ Riedlmayer, András J. "From the Ashes: The Past and Future of Bosnia's Cultural Heritage" (PDF). Harvard University.

- ^ "War Crimes in Bosnia-Hercegovina: U.N. Cease-Fire Won't Help Banja Luka". Human Rights Watch. 6 (8). June 1994.

- ^ Dakin, Brett (2002). "The Islamic Community in Bosnia and Herzegovina v. The Republika Srpska: Human Rights in a Multi-Ethnic Bosnia". Harvard Human Rights Journal. 15.

- ^ "Serbs ordered to pay for mosques". BBC News. 20 February 2009.

- ^ "Bridging the Gap in Srebrenica, Bosnia and Herzegovina". ICTY. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- ^ a b "Prosecutor v. Radovan Karadžić – Third Amended Indictment" (PDF). United Nations International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 27 February 2009.

- ^ "Srebrenica Suspects Revealed". Institute for War & Peace Reporting. 25 August 2006. Archived from the original on 16 April 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ Wood, Nicholas (1 March 2007). "Serbs Apologize To War Victims". The New York Times.

- ^ Mojzes, Paul (2011). Balkan Genocides: Holocaust and Ethnic Cleansing in the Twentieth Century. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-44220-665-6.

- ^ "Oric's Two Years". Human Rights Watch. 11 July 2006.

- ^ "ICTY Weekly Press Briefing, July 2005". United Nations. 5 March 2007. Archived from the original on 10 May 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- ^ "The Myth of Bratunac: A Blatant Numbers Game". idc.org. Research and Documentation Centre. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009.

- ^ Niksic, Sabina (9 October 2017). "Bosnian court acquits ex-Srebrenica commander of war crimes". Associated Press.

Serbs continue to claim the 1995 Srebrenica slaughter was an act of revenge by uncontrolled troops because they say that soldiers under Oric's command killed thousands of Serbs in the villages surrounding the eastern town

- ^ Serbs accuse world of ignoring their suffering, AKI, 13 July 2006

- ^ John Kifner (27 January 1994). "Yugoslav Army Reported Fighting In Bosnia to Help Serbian Forces". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ Halimović, Dženana (12 April 2017). "Ruski i grčki dobrovoljci u ratu u BiH". Radio Slobodna Evropa.

Haški tribunal procjenjuje kako je u redovima VRS bilo je između 529 i 614 ratnika iz Rusije, Grčke, Rumunije.

- ^ Balkan Battlegrounds: A Military History of the Yugoslav Conflict, 1990-1995, Volume 2. Central Intelligence Agency. 2002. pp. 266–268. ISBN 9780160664724.

- ^ Parker, Randall E.; Whaples, Robert M., eds. (2013). Routledge Handbook of Major Events in Economic History. Routledge. p. 374. ISBN 9781135080808.

- ^ a b Wilson, Paul (2019). Hostile Money: Currencies in Conflict. The History Press. ISBN 9780750991780.

- ^ a b Dobbins, James; Lesser, Ian O.; Chalk, Peter, eds. (2003). America's Role in Nation-Building: From Germany to Iraq. Rand Corporation. p. 104. ISBN 9780833034861.

- ^ Chami, Ralph; Espinoza, Rapahel; Dickinson, Fairleigh S.; Montiel, Peter J., eds. (2021). Macroeconomic Policy in Fragile States. Oxford University Press. pp. 357–358. ISBN 9780198853091.

- ^ Churchill et al. 1997, p. 1.

- ^ Bosnia and Herzegovina: From Recovery to Sustainable Growth. World Bank. 1997. pp. 8, 13–16. ISBN 9780821339220.

- ^ Bideleux, Robert; Jeffries, Ian, eds. (2007). The Balkans: A Post-Communist History. Routledge. pp. 393–394. ISBN 9781134583287.

- ^ Churchill et al. 1997, p. 4.

- ^ Churchill et al. 1997, p. 3.

- ^ Churchill et al. 1997, p. 6.

- ^ Lukac, Dusko (2008). Key Success Factors for Foreign Direct Investment (FDI): The Case of FDI in Western Balkan. Diplomica Verlag. p. 34. ISBN 9783836661690.

- ^ Bollens, Scott A. (2007). Cities, Nationalism and Democratization. Routledge. p. 97. ISBN 9781134111831.

- ^ "Violence against minorities in Republika Srpska must stop". Amnesty International. 11 October 2001.

- ^ McMahon, Robert (9 May 2001). "UN: Officials Alarmed By Mob Violence in Bosnia". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- ^ Strauss, Julius (8 May 2001). "Serb mob attacks Muslims". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ "UN condemns Serb 'sickness'". BBC. 8 May 2001.

- ^ "Bosnian Serb Crowd Beats Muslims at Mosque Rebuilding". The New York Times. 8 May 2001. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- ^ Report about Case Srebrenica – Banja Luka, 2002

- ^ Imaginary Massacres?, TIME Magazine, 11 September 2002

- ^ "DECISION ON ADMISSIBILITY AND MERITS – The Srebrenica Cases (49 applications) against The Republika Srpska" (PDF). Human Rights Chamber for Bosnia and Herzegovina. 7 March 2003. p. 50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Alic, Anes (20 October 2003). "Pulling Rotten Teeth". Transitions Online. Retrieved 2 May 2017.

- ^ Topić, Tanja (1 July 2004). "Otvaranje najmračnije stranice" (in Serbian). Vreme.

- ^ "Bosnian Serbs issue apology for massacre". Associated Press. 11 November 2004. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ^ "Bosnia Lawmakers Reject Srebrenica Resolution". Balkan Investigative Reporting Network. 8 April 2010.

- ^ "Envoy slams Bosnia Serbs for questioning Srebrenica". Reuters. 21 April 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

- ^ "RS Government Special Session A Distasteful Attempt to Question Genocide". OHR. 21 April 2010. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 21 April 2010.

Sources

[edit]- Churchill, Stacy; Chang, Gwang-Chol; Dyankov, Alexander; Kolouh-Westin, Lidija; Uvalic-Trumbic, Stamenka (1997). "Review of the education system in the Republika Srpska, Bosnia and Herzegovina". unesco.org. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

- Burg, Steven L.; Shoup, Paul S. (1999). The War in Bosnia-Herzegovina: Ethnic Conflict and International Intervention (2nd ed.). M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 978-0-7656-3189-3.

- Trbovich, Ana S. (2008). A Legal Geography of Yugoslavia's Disintegration. Oxford University Press, US. ISBN 978-0-19-533343-5.

Further reading

[edit]- "A precarious peace", The Economist, 22 January 1998

External links

[edit] Media related to Republika Srpska (1992-1995) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Republika Srpska (1992-1995) at Wikimedia Commons

- History of Republika Srpska

- Former unrecognized countries

- Former republics in Europe

- History of the Serbs of Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Serbian nationalism in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- 1992 establishments in Europe

- 1995 disestablishments in Europe

- Politics of Yugoslavia

- Administrative divisions of Yugoslavia

- Former subdivisions of Bosnia and Herzegovina