Colombia

Republic of Colombia República de Colombia (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Libertad y Orden" (Spanish) "Freedom and Order" | |

| Anthem: Himno Nacional de la República de Colombia (Spanish) "National Anthem of the Republic of Colombia" | |

Location of Colombia (dark green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Bogotá 4°35′N 74°4′W / 4.583°N 74.067°W |

| Official languages | Spanish |

| Recognized regional languages | Creole English (in San Andrés and Providencia)[1] 64 other languages[a] |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Religion (2022)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Colombian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Gustavo Petro | |

| Francia Márquez | |

| Legislature | Congress |

| Senate | |

| Chamber of Representatives | |

| Independence from Spain | |

• Declared | 20 July 1810 |

• Recognized | 7 August 1819 |

• Last unitisation | 5 August 1886 |

• Secession of Panama | 6 November 1903 |

| 4 July 1991 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,141,748 km2 (440,831 sq mi) (25th) |

• Water (%) | 2.1 (as of 2015)[5] |

| Population | |

• 2024 estimate | |

• Density | 46.15/km2 (119.5/sq mi) (174th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | high inequality |

| HDI (2022) | high (91st) |

| Currency | Colombian peso (COP) |

| Time zone | UTC−5[b] (COT) |

| Date format | DMY |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | +57 |

| ISO 3166 code | CO |

| Internet TLD | .co |

| |

Colombia,[b] officially the Republic of Colombia,[c] is a country primarily located in South America with insular regions in North America. The Colombian mainland is bordered by the Caribbean Sea to the north, Venezuela to the east and northeast, Brazil to the southeast, Ecuador and Peru to the south and southwest, the Pacific Ocean to the west, and Panama to the northwest. Colombia is divided into 32 departments. The Capital District of Bogotá is also the country's largest city hosting the main financial and cultural hub. Other major urban areas include Medellín, Cali, Barranquilla, Cartagena, Santa Marta, Cúcuta, Ibagué, Villavicencio and Bucaramanga. It covers an area of 1,141,748 square kilometers (440,831 sq mi) and has a population of around 52 million. Its rich cultural heritage[15]—including language, religion, cuisine, and art—reflects its history as a colony, fusing cultural elements brought by immigration from Europe[16][17][18][19] and the Middle East,[20][21][22] with those brought by the African diaspora,[23] as well as with those of the various Indigenous civilizations that predate colonization.[24] Spanish is the official language, although Creole, English and 64 other languages are recognized regionally.

Colombia has been home to many indigenous peoples and cultures since at least 12,000 BCE. The Spanish first landed in La Guajira in 1499, and by the mid-16th century, they had colonized much of present-day Colombia, and established the New Kingdom of Granada, with Santa Fé de Bogotá as its capital. Independence from the Spanish Empire was achieved in 1819, with what is now Colombia emerging as the United Provinces of New Granada. The new polity experimented with federalism as the Granadine Confederation (1858) and then the United States of Colombia (1863), before becoming a republic—the current Republic of Colombia—in 1886. With the backing of the United States and France, Panama seceded from Colombia in 1903, resulting in Colombia's present borders. Beginning in the 1960s, the country has suffered from an asymmetric low-intensity armed conflict and political violence, both of which escalated in the 1990s. Since 2005, there has been significant improvement in security, stability, and rule of law, as well as unprecedented economic growth and development.[25][26] Colombia is recognized for its healthcare system, being the best healthcare in Latin America according to the World Health Organization and 22nd in the world.[27][28] Its diversified economy is the third-largest in South America, with macroeconomic stability and favorable long-term growth prospects.[29][30]

Colombia is one of the world's seventeen megadiverse countries; it has the highest level of biodiversity per square mile in the world and the second-highest level overall.[31] Its territory encompasses Amazon rainforest, highlands, grasslands and deserts. It is the only country in South America with coastlines (and islands) along both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Colombia is a key member of major global and regional organizations including the UN, the WTO, the OECD, the OAS, the Pacific Alliance and the Andean Community; it is also a NATO Global Partner[32] and a major non-NATO ally of the United States.[33]

Etymology

The name "Colombia" is derived from the last name of the Italian navigator Christopher Columbus (Latin: Christophorus Columbus, Italian: Cristoforo Colombo, Spanish: Cristóbal Colón). It was conceived as a reference to all of the New World.[34] The name was later adopted by the Republic of Colombia of 1819, formed from the territories of the old Viceroyalty of New Granada (modern-day Colombia, Panama, Venezuela, Ecuador, and northwest Brazil).[35]

When Venezuela, Ecuador, and Cundinamarca came to exist as independent states, the former Department of Cundinamarca adopted the name "Republic of New Granada". New Granada officially changed its name in 1858 to the Granadine Confederation. In 1863 the name was again changed, this time to United States of Colombia, before finally adopting its present name – the Republic of Colombia – in 1886.[35]

To refer to this country, the Colombian government uses the terms Colombia and República de Colombia.[36]

History

Pre-Columbian era

Owing to its location, the present territory of Colombia was a corridor of early human civilization from Mesoamerica and the Caribbean to the Andes and Amazon basin. The oldest archaeological finds are from the Pubenza and El Totumo sites in the Magdalena Valley 100 kilometers (62 mi) southwest of Bogotá.[37] These sites date from the Paleoindian period (18,000–8000 BCE). At Puerto Hormiga and other sites, traces from the Archaic Period (~8000–2000 BCE) have been found. Vestiges indicate that there was also early occupation in the regions of El Abra and Tequendama in Cundinamarca. The oldest pottery discovered in the Americas, found in San Jacinto, dates to 5000–4000 BCE.[38]

Indigenous people inhabited the territory that is now Colombia by 12,500 BCE. Nomadic hunter-gatherer tribes at the El Abra, Tibitó and Tequendama sites near present-day Bogotá traded with one another and with other cultures from the Magdalena River Valley.[39] A site including eight miles (13 km) of pictographs that is under study at Serranía de la Lindosa was revealed in November 2020.[40] Their age is suggested as being 12,500 years old (c. 10,480 B.C.) by the anthropologists working on the site, because of extinct fauna depicted. It was during the earliest known human occupation of the area.

Between 5000 and 1000 BCE, hunter-gatherer tribes transitioned to agrarian societies; fixed settlements were established, and pottery appeared. Beginning in the 1st millennium BCE, groups of Amerindians including the Muisca, Zenú, Quimbaya, and Tairona developed the political system of cacicazgos with a pyramidal structure of power headed by caciques. The Muisca inhabited mainly the area of what is now the Departments of Boyacá and Cundinamarca high plateau (Altiplano Cundiboyacense) where they formed the Muisca Confederation. They farmed maize, potato, quinoa, and cotton, and traded gold, emeralds, blankets, ceramic handicrafts, coca and especially rock salt with neighboring nations. The Tairona inhabited northern Colombia in the isolated mountain range of Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta.[41] The Quimbaya inhabited regions of the Cauca River Valley between the Western and Central Ranges of the Colombian Andes.[42] Most of the Amerindians practiced agriculture and the social structure of each indigenous community was different. Some groups of indigenous people such as the Caribs lived in a state of permanent war, but others had less bellicose attitudes.[43] During the 1200s, Malayo-Polynesians and Native Americans in Colombia made contact, thereby spreading Native American genetics from Precolonial Colombia to some Pacific Ocean islands.[44][45]

Colonial period

Alonso de Ojeda (who had sailed with Columbus) reached the Guajira Peninsula in 1499.[46][47] Spanish explorers, led by Rodrigo de Bastidas, made the first exploration of the Caribbean coast in 1500.[48] Christopher Columbus navigated near the Caribbean in 1502.[49] In 1508, Vasco Núñez de Balboa accompanied an expedition to the territory through the region of Gulf of Urabá and they founded the town of Santa María la Antigua del Darién in 1510, the first stable settlement on the continent. [d][50] Santa Marta was founded in 1525,[51] and Cartagena in 1533.[52] Spanish conquistador Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada led an expedition to the interior in April 1536, and christened the districts through which he passed "New Kingdom of Granada". In August 1538, he provisionally founded its capital near the Muisca cacicazgo of Muyquytá, and named it "Santa Fe". The name soon acquired a suffix and was called Santa Fe de Bogotá.[53][54] Two other notable journeys by early conquistadors to the interior took place in the same period. Sebastián de Belalcázar, conqueror of Quito, traveled north and founded Cali, in 1536, and Popayán, in 1537;[55] from 1536 to 1539, German conquistador Nikolaus Federmann crossed the Llanos Orientales and went over the Cordillera Oriental in a search for El Dorado, the "city of gold".[56][57] The legend and the gold would play a pivotal role in luring the Spanish and other Europeans to New Granada during the 16th and 17th centuries.[58]

The conquistadors made frequent alliances with the enemies of different indigenous communities. Indigenous allies were crucial to conquest, as well as to creating and maintaining empire.[59] Indigenous peoples in Colombia experienced a decline in population due to conquest as well as Eurasian diseases, such as smallpox, to which they had no immunity.[60][61] Regarding the land as deserted, the Spanish Crown sold properties to all persons interested in colonized territories, creating large farms and possession of mines.[62][63][64] In the 16th century, the nautical science in Spain reached a great development thanks to numerous scientific figures of the Casa de Contratación and nautical science was an essential pillar of the Iberian expansion.[65] In 1542, the region of New Granada, along with all other Spanish possessions in South America, became part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, with its capital in Lima.[66] In 1547, New Granada became a separate captaincy-general within the viceroyalty, with its capital at Santa Fe de Bogota.[67] In 1549, the Royal Audiencia was created by a royal decree, and New Granada was ruled by the Royal Audience of Santa Fe de Bogotá, which at that time comprised the provinces of Santa Marta, Rio de San Juan, Popayán, Guayana and Cartagena.[68] But important decisions were taken from the colony to Spain by the Council of the Indies.[69][70]

In the 16th century, European slave traders had begun to bring enslaved Africans to the Americas. Spain was the only European power that did not establish factories in Africa to purchase slaves; the Spanish Empire instead relied on the asiento system, awarding merchants from other European nations the license to trade enslaved peoples to their overseas territories.[72][73] This system brought Africans to Colombia, although many spoke out against the institution.[e][f] The indigenous peoples could not be enslaved because they were legally subjects of the Spanish Crown.[78] To protect the indigenous peoples, several forms of land ownership and regulation were established by the Spanish colonial authorities: resguardos, encomiendas and haciendas.[62][63][64]

However, secret anti-Spanish discontentment was already brewing for Colombians since Spain prohibited direct trade between the Viceroyalty of Peru, which included Colombia, and the Viceroyalty of New Spain, which included the Philippines, the source of Asian products like silk and porcelain which was in demand in the Americas. Illegal trade between Peruvians, Filipinos, and Mexicans continued in secret, as smuggled Asian goods ended up in Córdoba, Colombia, the distribution center for illegal Asian imports, due to the collusion between these peoples against the authorities in Spain. They settled and traded with each other while disobeying the forced Spanish monopoly.[79]

The Viceroyalty of New Granada was established in 1717, then temporarily removed, and then re-established in 1739. Its capital was Santa Fé de Bogotá. This Viceroyalty included some other provinces of northwestern South America that had previously been under the jurisdiction of the Viceroyalties of New Spain or Peru and correspond mainly to today's Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama. Bogotá became one of the principal administrative centers of the Spanish possessions in the New World, along with Lima and Mexico City, though it remained less developed compared to those two cities in several economic and logistical ways.[80][81]

Great Britain declared war on Spain in 1739, and the city of Cartagena quickly became a top target for the British. A massive British expeditionary force was dispatched to capture the city, but, after achieving initial inroads, devastating outbreaks of disease crippled their numbers, and the British were forced to withdraw. The battle became one of Spain's most decisive victories in the conflict, and secured Spanish dominance in the Caribbean until the Seven Years' War.[71][82] The 18th-century priest, botanist, and mathematician José Celestino Mutis was delegated by Viceroy Antonio Caballero y Góngora to conduct an inventory of the nature of New Granada. Started in 1783, this became known as the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Granada. It classified plants and wildlife, and founded the first astronomical observatory in the city of Santa Fe de Bogotá.[83] In July 1801 the Prussian scientist Alexander von Humboldt reached Santa Fe de Bogotá where he met with Mutis. In addition, historical figures in the process of independence in New Granada emerged from the expedition as the astronomer Francisco José de Caldas, the scientist Francisco Antonio Zea, the zoologist Jorge Tadeo Lozano and the painter Salvador Rizo.[84][85]

Independence

The accessibility of this section is in question. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. (November 2024) |

Rebellions against Spanish rule had occurred in the empire since the advent of conquest and colonization, but most were either crushed or remained too weak to change the overall situation. The last one that sought outright independence from Spain sprang up around 1810 and culminated in the Colombian Declaration of Independence, issued on 20 July 1810, the day that is now celebrated as the nation's Independence Day.[86] This movement followed the independence of Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) in 1804, which provided some support to an eventual leader of this rebellion: Simón Bolívar. Francisco de Paula Santander also would play a decisive role.[87][88][89]

A movement was initiated by Antonio Nariño, who opposed Spanish centralism and led the opposition against the Viceroyalty.[90] Cartagena became independent in November 1811.[91] In 1811, the United Provinces of New Granada were proclaimed, headed by Camilo Torres Tenorio.[92][93] The emergence of two distinct ideological currents among the patriots (federalism and centralism) gave rise to a period of instability called the Patria Boba.[94] Shortly after the Napoleonic Wars ended, Ferdinand VII, recently restored to the throne in Spain, unexpectedly decided to send military forces to retake most of northern South America. The viceroyalty was restored under the command of Juan de Sámano, whose regime punished those who participated in the patriotic movements, ignoring the political nuances of the juntas.[95] The retribution stoked renewed rebellion, which, combined with a weakened Spain, made possible a successful rebellion led by the Venezuelan-born Simón Bolívar, who finally proclaimed independence in 1819.[96][97] The pro-Spanish resistance was defeated in 1822 in the present territory of Colombia and in 1823 in Venezuela.[98][99][100] During the Independence War, between 250 and 400 thousand people (12–20% of the pre-war population) died.[101][102][103]

The territory of the Viceroyalty of New Granada became the Republic of Colombia, organized as a union of the current territories of Colombia, Panama, Ecuador, Venezuela, parts of Guyana and Brazil and north of Marañón River.[104] The Congress of Cúcuta in 1821 adopted a constitution for the new Republic.[105][106] Simón Bolívar became the first President of Colombia, and Francisco de Paula Santander was made Vice President.[107] However, the new republic was unstable and the Gran Colombia ultimately collapsed.

Modern Colombia comes from one of the countries that emerged after the dissolution of Gran Colombia, the other two being Ecuador and Venezuela.[108][109][110] Colombia was the first constitutional government in South America,[111] and the Liberal and Conservative parties, founded in 1848 and 1849, respectively, are two of the oldest surviving political parties in the Americas.[112] Slavery was abolished in the country in 1851.[113][114]

Internal political and territorial divisions led to the dissolution of Gran Colombia in 1830.[108][109] The so-called "Department of Cundinamarca" adopted the name "New Granada", which it kept until 1858 when it became the "Confederación Granadina" (Granadine Confederation). After a two-year civil war in 1863, the United States of Colombia was created, which became known as the Republic of Colombia in 1886.[111][115] Internal divisions remained between the bipartisan political forces, occasionally igniting very bloody civil wars, the most significant being the Thousand Days' War (1899–1902), in which between 100 and 180 thousand Colombians lost their lives when the Liberal Party, supported by Venezuela, Ecuador, Nicaragua, and Guatemala rebelled against the Nationalist government and took control of Santander, ultimately being defeated in 1902 by nationalist forces.[116]

20th century

The United States of America's intentions to influence the area (especially the Panama Canal construction and control)[117] led to the separation of the Department of Panama in 1903 and the establishment of it as a nation.[118] The United States paid Colombia $25,000,000 in 1921, seven years after completion of the canal, for redress of President Roosevelt's role in the creation of Panama, and Colombia recognized Panama under the terms of the Thomson–Urrutia Treaty.[119] Colombia and Peru went to war because of territory disputes far in the Amazon basin. The war ended with a peace deal brokered by the League of Nations. The League finally awarded the disputed area to Colombia in June 1934.[120]

Soon after, Colombia achieved some degree of political stability, which was interrupted by a bloody conflict that took place between the late 1940s and the early 1950s, a period known as La Violencia ("The Violence"). Its cause was mainly mounting tensions between the two leading political parties, which subsequently ignited after the assassination of the Liberal presidential candidate Jorge Eliécer Gaitán on 9 April 1948.[121][122] The ensuing riots in Bogotá, known as El Bogotazo, spread throughout the country and claimed the lives of at least 180,000 Colombians.[123]

Colombia entered the Korean War when Laureano Gómez was elected president. It was the only Latin American country to join the war in a direct military role as an ally of the United States. Particularly important was the resistance of the Colombian troops at Old Baldy.[124]

The violence between the two political parties decreased first when Gustavo Rojas deposed the President of Colombia in a coup d'état and negotiated with the guerrillas, and then under the military junta of General Gabriel París.[125][126]

After Rojas' deposition, the Colombian Conservative Party and the Colombian Liberal Party agreed to create the National Front, a coalition that would jointly govern the country. Under the deal, the presidency would alternate between conservatives and liberals every 4 years for 16 years; the two parties would have parity in all other elective offices.[127] The National Front ended "La Violencia", and National Front administrations attempted to institute far-reaching social and economic reforms in cooperation with the Alliance for Progress.[128][129] Despite the progress in certain sectors, many social and political problems continued, and guerrilla groups were formally created such as the FARC, the ELN and the M-19 to fight the government and political apparatus.[130]

Since the 1960s, the country has suffered from an asymmetric low-intensity armed conflict between government forces, leftist guerrilla groups and right wing paramilitaries.[131] The conflict escalated in the 1990s,[132] mainly in remote rural areas.[133] Since the beginning of the armed conflict, human rights defenders have fought for the respect for human rights, despite staggering opposition.[g][h] Several guerrillas' organizations decided to demobilize after peace negotiations in 1989–1994.[25]

The United States has been heavily involved in the conflict since its beginnings, when in the early 1960s the U.S. government encouraged the Colombian military to attack leftist militias in rural Colombia. This was part of the U.S. fight against communism. Mercenaries and multinational corporations such as Chiquita Brands International are some of the international actors that have contributed to the violence of the conflict.[131][25][137]

Beginning in the mid-1970s Colombian drug cartels became major producers, processors and exporters of illegal drugs, primarily marijuana and cocaine.[138]

On 4 July 1991, a new Constitution was promulgated. The changes generated by the new constitution are viewed as positive by Colombian society.[139][140]

21st century

The administration of President Álvaro Uribe (2002–2010) adopted the democratic security policy which included an integrated counter-terrorism and counter-insurgency campaign.[141] The government economic plan also promoted confidence in investors.[142] As part of a controversial peace process, the AUC (right-wing paramilitaries) had ceased to function formally as an organization .[143] In February 2008, millions of Colombians demonstrated against FARC and other outlawed groups.[144]

After peace negotiations in Cuba, the Colombian government of President Juan Manuel Santos and the guerrillas of the FARC-EP announced a final agreement to end the conflict.[145] However, a referendum to ratify the deal was unsuccessful.[146][147] Afterward, the Colombian government and the FARC signed a revised peace deal in November 2016,[148] which the Colombian congress approved.[149] In 2016, President Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.[150] The Government began a process of attention and comprehensive reparation for victims of conflict.[151][152] Colombia shows modest progress in the struggle to defend human rights, as expressed by HRW.[153] A Special Jurisdiction of Peace has been created to investigate, clarify, prosecute and punish serious human rights violations and grave breaches of international humanitarian law which occurred during the armed conflict and to satisfy victims' right to justice.[154] During his visit to Colombia, Pope Francis paid tribute to the victims of the conflict.[155]

In June 2018, Iván Duque, the candidate of the right-wing Democratic Center party, won the presidential election.[156] On 7 August 2018, he was sworn in as the new President of Colombia to succeed Juan Manuel Santos.[157] Colombia's relations with Venezuela have fluctuated due to ideological differences between the two governments.[158] Colombia has offered humanitarian support with food and medicines to mitigate the shortage of supplies in Venezuela.[159] Colombia's Foreign Ministry said that all efforts to resolve Venezuela's crisis should be peaceful.[160] Colombia proposed the idea of the Sustainable Development Goals and a final document was adopted by the United Nations.[161] In February 2019, Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro cut off diplomatic relations with Colombia after Colombian President Ivan Duque had helped Venezuelan opposition politicians deliver humanitarian aid to their country. Colombia recognized Venezuelan opposition leader Juan Guaidó as the country's legitimate president. In January 2020, Colombia rejected Maduro's proposal that the two countries restore diplomatic relations.[162]

Protests started on 28 April 2021 when the government proposed a tax bill that would greatly expand the range of the 19 percent value-added tax.[163] The 19 June 2022 election run-off vote ended in a win for former guerrilla, Gustavo Petro, taking 50.47% of the vote compared to 47.27% for independent candidate Rodolfo Hernández. The single-term limit for the country's presidency prevented President Iván Duque from seeking re-election. On 7 August 2022, Petro was sworn in, becoming the country's first leftist president.[164][165]

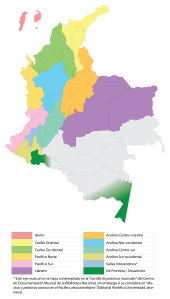

Geography

The geography of Colombia is characterized by its six main natural regions that present their unique characteristics, from the Andes mountain range region; the Pacific Coastal region; the Caribbean coastal region; the Llanos (plains); the Amazon rainforest region; to the insular area, comprising islands in both the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.[166] It shares its maritime limits with Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Jamaica, Haiti, and the Dominican Republic.[167]

Colombia is bordered to the northwest by Panama, to the east by Venezuela and Brazil, and to the south by Ecuador and Peru;[168] it established its maritime boundaries with neighboring countries through seven agreements on the Caribbean Sea and three on the Pacific Ocean.[167] It lies between latitudes 12°N and 4°S and between longitudes 67° and 79°W.

East of the Andes lies the savanna of the Llanos, part of the Orinoco River basin, and in the far southeast, the jungle of the Amazon rainforest. Together these lowlands make up over half Colombia's territory, but they contain less than 6% of the population. To the north the Caribbean coast, home to 21.9% of the population and the location of the major port cities of Barranquilla and Cartagena, generally consists of low-lying plains, but it also contains the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta mountain range, which includes the country's tallest peaks (Pico Cristóbal Colón and Pico Simón Bolívar), and the La Guajira Desert. By contrast the narrow and discontinuous Pacific coastal lowlands, backed by the Serranía de Baudó mountains, are sparsely populated and covered in dense vegetation. The principal Pacific port is Buenaventura.[166][169][170]

Part of the Ring of Fire, a region of the world subject to earthquakes and volcanic eruptions,[171] in the interior of Colombia the Andes are the prevailing geographical feature. Most of Colombia's population centers are located in these interior highlands. Beyond the Colombian Massif (in the southwestern departments of Cauca and Nariño), these are divided into three branches known as cordilleras (mountain ranges): the Cordillera Occidental, running adjacent to the Pacific coast and including the city of Cali; the Cordillera Central, running between the Cauca and Magdalena River valleys (to the west and east, respectively) and including the cities of Medellín, Manizales, Pereira, and Armenia; and the Cordillera Oriental, extending northeast to the Guajira Peninsula and including Bogotá, Bucaramanga, and Cúcuta.[166][169][170] Peaks in the Cordillera Occidental exceed 4,700 m (15,420 ft), and in the Cordillera Central and Cordillera Oriental they reach 5,000 m (16,404 ft). At 2,600 m (8,530 ft), Bogotá is the highest city of its size in the world.[166]

The main rivers of Colombia are Magdalena, Cauca, Guaviare, Atrato, Meta, Putumayo and Caquetá. Colombia has four main drainage systems: the Pacific drain, the Caribbean drain, the Orinoco Basin and the Amazon Basin. The Orinoco and Amazon Rivers mark limits with Colombia to Venezuela and Peru respectively.[172]

Climate

The climate of Colombia is characterized for being tropical presenting variations within six natural regions and depending on the altitude, temperature, humidity, winds and rainfall.[173] Colombia has a diverse range of climate zones, including tropical rainforests, savannas, steppes, deserts and mountain climates.

Mountain climate is one of the unique features of the Andes and other high altitude reliefs where climate is determined by elevation. Below 1,000 meters (3,281 ft) in elevation is the warm altitudinal zone, where temperatures are above 24 °C (75.2 °F). About 82.5% of the country's total area lies in the warm altitudinal zone. The temperate climate altitudinal zone located between 1,001 and 2,000 meters (3,284 and 6,562 ft) is characterized for presenting an average temperature ranging between 17 and 24 °C (62.6 and 75.2 °F). The cold climate is present between 2,001 and 3,000 meters (6,565 and 9,843 ft) and the temperatures vary between 12 and 17 °C (53.6 and 62.6 °F). Beyond lies the alpine conditions of the forested zone and then the treeless grasslands of the páramos. Above 4,000 meters (13,123 ft), where temperatures are below freezing, the climate is glacial, a zone of permanent snow and ice.[173]

Biodiversity and conservation

Colombia is one of the megadiverse countries in biodiversity,[174] ranking first in bird species.[175] Colombia is the country with the planet's highest biodiversity, having the highest rate of species by area as well as the largest number of endemisms (species that are not found naturally anywhere else) of any country. About 10% of the species of the Earth live in Colombia, including over 1,900 species of bird, more than in Europe and North America combined. Colombia has 10% of the world's mammals species, 14% of the amphibian species and 18% of the bird species of the world.[176]

As for plants, the country has between 40,000 and 45,000 plant species, equivalent to 10 or 20% of total global species, which is even more remarkable given that Colombia is considered a country of intermediate size.[178] Colombia is the second most biodiverse country in the world, lagging only after Brazil which is approximately 7 times bigger.[31]

Colombia has about 2,000 species of marine fish and is the second most diverse country in freshwater fish. It is also the country with the most endemic species of butterflies, is first in orchid species, and has approximately 7,000 species of beetles. Colombia is second in the number of amphibian species and is the third most diverse country in reptiles and palms. There are about 1,900 species of mollusks and according to estimates there are about 300,000 species of invertebrates in the country. In Colombia there are 32 terrestrial biomes and 314 types of ecosystems.[179][180]

Protected areas and the "National Park System" cover an area of about 14,268,224 hectares (142,682.24 km2) and account for 12.77% of the Colombian territory.[181] Compared to neighboring countries, rates of deforestation in Colombia are still relatively low.[182] Colombia had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 8.26/10, ranking it 25th globally out of 172 countries.[183] Colombia is the sixth country in the world by magnitude of total renewable freshwater supply, and still has large reserves of freshwater.[184]

Government and politics

The government of Colombia takes place within the framework of a presidential participatory democratic republic as established in the Constitution of 1991.[140] In accordance with the principle of separation of powers, government is divided into three branches: the executive branch, the legislative branch and the judicial branch.[185]

As the head of the executive branch, the President of Colombia serves as both head of state and head of government, followed by the Vice President and the Council of Ministers. The president is elected by popular vote to serve a single four-year term (In 2015, Colombia's Congress approved the repeal of a 2004 constitutional amendment that changed the one-term limit for presidents to a two-term limit).[186] At the provincial level executive power is vested in department governors, municipal mayors and local administrators for smaller administrative subdivisions, such as corregimientos or comunas.[187] All regional elections are held one year and five months after the presidential election.[188][189]

The legislative branch of government is represented nationally by the Congress, a bicameral institution comprising a 166-seat Chamber of Representatives and a 102-seat Senate.[190][191] The Senate is elected nationally and the Chamber of Representatives is elected in electoral districts.[192] Members of both houses are elected to serve four-year terms two months before the president, also by popular vote.[193]

The judicial branch is headed by four high courts,[194] consisting of the Supreme Court which deals with penal and civil matters, the Council of State, which has special responsibility for administrative law and also provides legal advice to the executive, the Constitutional Court, responsible for assuring the integrity of the Colombian constitution, and the Superior Council of Judicature, responsible for auditing the judicial branch.[195] Colombia operates a system of civil law, which since 1991 has been applied through an adversarial system.[196]

Despite a number of controversies, the democratic security policy has ensured that former President Álvaro Uribe remained popular among Colombian people, with his approval rating peaking at 76%, according to a poll in 2009.[197] However, having served two terms, he was constitutionally barred from seeking re-election in 2010.[198] In the run-off elections on 20 June 2010 the former Minister of Defense Juan Manuel Santos won with 69% of the vote against the second most popular candidate, Antanas Mockus. A second round was required since no candidate received over the 50% winning threshold of votes.[199] Santos won re-election with nearly 51% of the vote in second-round elections on 15 June 2014, beating right-wing rival Óscar Iván Zuluaga, who won 45%.[200] In 2018, Iván Duque won in the second round of the election with 54% of the vote, against 42% for his left-wing rival, Gustavo Petro. His term as Colombia's president ran for four years, beginning on 7 August 2018.[201] In 2022, Colombia elected Gustavo Petro, who became its first leftist leader,[202] and Francia Marquez, who was the first black person elected as vice president.[203]

Foreign affairs

The foreign affairs of Colombia are headed by the President, as head of state, and managed by the Minister of Foreign Affairs.[204] Colombia has diplomatic missions in all continents.[205]

Colombia was one of the four founding members of the Pacific Alliance, which is a political, economic and co-operative integration mechanism that promotes the free circulation of goods, services, capital and persons between the members, as well as a common stock exchange and joint embassies in several countries.[206] Colombia is also a member of the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the Organization of American States, the Organization of Ibero-American States, and the Andean Community of Nations.[207][208][209][210][211]

Colombia is a global partner of NATO[212] and a major non-NATO ally of the United States.[33]

Military

The executive branch of government is responsible for managing the defense of Colombia, with the President commander-in-chief of the armed forces. The Ministry of Defence exercises day-to-day control of the military and the Colombian National Police. Colombia has 455,461 active military personnel.[213] In 2016, 3.4% of the country's GDP went towards military expenditure, placing it 24th in the world. Colombia's armed forces are the largest in Latin America, and it is the second largest spender on its military after Brazil.[214][215] In 2018, Colombia signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[216]

The Colombian military is divided into three branches: the National Army of Colombia; the Colombian Aerospace Force; and the Colombian Navy. The National Police functions as a gendarmerie, operating independently from the military as the law enforcement agency for the entire country. Each of these operates with their own intelligence apparatus separate from the National Intelligence Directorate (DNI, in Spanish).[217]

The National Army is formed by divisions, brigades, special brigades, and special units,[218] the Colombian Navy by the Naval Infantry, the Naval Force of the Caribbean, the Naval Force of the Pacific, the Naval Force of the South, the Naval Force of the East, Colombia Coast Guards, Naval Aviation, and the Specific Command of San Andres y Providencia[219] and the Aerospace Force by 15 air units.[220]

Administrative divisions

Colombia is divided into 32 departments and one capital district, which is treated as a department (Bogotá also serves as the capital of the department of Cundinamarca). Departments are subdivided into municipalities, each of which is assigned a municipal seat, and municipalities are in turn subdivided into corregimientos in rural areas and into comunas in urban areas. Each department has a local government with a governor and assembly directly elected to four-year terms, and each municipality is headed by a mayor and council. There is a popularly elected local administrative board in each of the corregimientos or comunas.[221][222][223][224]

In addition to the capital, four other cities have been designated districts (in effect special municipalities), on the basis of special distinguishing features. These are Barranquilla, Cartagena, Santa Marta and Buenaventura. Some departments have local administrative subdivisions, where towns have a large concentration of population and municipalities are near each other (for example, in Antioquia and Cundinamarca). Where departments have a low population (for example Amazonas, Vaupés and Vichada), special administrative divisions are employed, such as "department corregimientos", which are a hybrid of a municipality and a corregimiento.[221][222]

Click on a department on the map below to go to its article.

|

|

Economy

Historically an agrarian economy, Colombia urbanized rapidly in the 20th century, by the end of which just 15.8% of the workforce were employed in agriculture, generating just 6.6% of GDP; 20% of the workforce were employed in industry and 65% in services, responsible for 33% and 60% of GDP respectively.[225][226] The country's economic production is dominated by its strong domestic demand. Consumption expenditure by households is the largest component of GDP.[227][29][228]

Colombia's market economy grew steadily in the latter part of the 20th century, with gross domestic product (GDP) increasing at an average rate of over 4% per year between 1970 and 1998. The country suffered a recession in 1999 (the first full year of negative growth since the Great Depression), and the recovery was long and painful. However, growth reaching 7% in 2007, one of the highest in Latin America.[26] According to International Monetary Fund estimates, in 2023, Colombia's GDP (PPP) was US$1 trillion, 32nd in the world and third in South America, after Brazil and Argentina.

Total government expenditures account for 28% of the domestic economy. External debt equals 40% of gross domestic product. A strong fiscal climate was reaffirmed by a boost in bond ratings.[229][230][231] Annual inflation closed 2017 at 4.09% YoY (vs. 5.75% YoY in 2016).[232] The average national unemployment rate in 2017 was 9.4%,[233] although the informality is the biggest problem facing the labour market (the income of formal workers climbed 24.8% in 5 years while labor incomes of informal workers rose only 9%).[234] Colombia has free-trade zones (FTZ),[235] such as Zona Franca del Pacifico, located in the Valle del Cauca, one of the most striking areas for foreign investment.[236]

The financial sector has grown favorably due to good liquidity in the economy, the growth of credit and the positive performance of the Colombian economy.[30][237][238] The Colombian Stock Exchange through the Latin American Integrated Market (MILA) offers a regional market to trade equities.[239][240] Colombia is now one of only three economies with a perfect score on the strength of legal rights index, according to the World Bank.[241]

Colombia is rich in natural resources, and it is heavily dependent on energy and mining exports.[242] Colombia's main exports include mineral fuels, oils, distillation products, fruit and other agricultural products, sugars and sugar confectionery, food products, plastics, precious stones, metals, forest products, chemical goods, pharmaceuticals, vehicles, electronic products, electrical equipment, perfumery and cosmetics, machinery, manufactured articles, textile and fabrics, clothing and footwear, glass and glassware, furniture, prefabricated buildings, military products, home and office material, construction equipment, software, among others.[243] Principal trading partners are the United States, China, the European Union and some Latin American countries.[244][245]

Non-traditional exports have boosted the growth of Colombian foreign sales as well as the diversification of destinations of export thanks to new free trade agreements.[246] Recent economic growth has led to a considerable increase of new millionaires, including the new entrepreneurs, Colombians with a net worth exceeding US$1 billion.[247][248]

In 2017, however, the National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) reported that 26.9% of the population were living below the poverty line, of which 7.4% were in "extreme poverty". The multidimensional poverty rate stands at 17.0 percent of the population.[249] The Government has also been developing a process of financial inclusion within the country's most vulnerable population.[250]

The contribution of tourism to GDP was US$5,880.3bn (2.0% of total GDP) in 2016. Tourism generated 556,135 jobs (2.5% of total employment) in 2016.[251] Foreign tourist visits were predicted to have risen from 0.6 million in 2007 to 4 million in 2017.[252][253]

Agriculture and natural resources

In agriculture, Colombia is one of the five largest producers in the world of coffee, avocado and palm oil, and one of the 10 largest producers in the world of sugarcane, banana, pineapple and cocoa. The country also has considerable production of rice, potato and cassava. Although it is not the largest coffee producer in the world (Brazil claims that title), the country has been able to carry out, for decades, a global marketing campaign to add value to the country's product. Colombian palm oil production is one of the most sustainable on the planet, compared to the largest existing producers. Colombia is also among the 20 largest producers in the world of beef and chicken meat.[254][255][256] Colombia is also the 2nd largest flower exporter in the world, after the Netherlands.[257] Colombian agriculture emits 55% of Colombia's greenhouse gas emissions, mostly from deforestation, over-extensive cattle ranching, land grabbing, and illegal agriculture.[258]

Colombia is an important exporter of coal and petroleum – in 2020, more than 40% of the country's exports were based on these two products.[259] In 2018 it was the 5th largest coal exporter in the world.[260] In 2019, Colombia was the 20th largest petroleum producer in the world, with 791 thousand barrels/day, exporting a good part of its production – the country was the 19th largest oil exporter in the world in 2020.[261] In mining, Colombia is the world's largest producer of emerald,[262] and in the production of gold, between 2006 and 2017, the country produced 15 tons per year until 2007, when its production increased significantly, beating the record of 66.1 tons extracted in 2012. In 2017, it extracted 52.2 tons. Currently, the country is among the 25 largest gold producers in the world.[263]

Energy and transportation

The electricity production in Colombia comes mainly from Renewable energy sources. 69.93% is obtained from the hydroelectric generation.[264] Colombia's commitment to renewable energy was recognized in the 2014 Global Green Economy Index (GGEI), ranking among the top 10 nations in the world in terms of greening efficiency sectors.[265]

Transportation in Colombia is regulated within the functions of the Ministry of Transport[266] and entities such as the National Roads Institute (INVÍAS) responsible for the Highways in Colombia,[267] the Aerocivil, responsible for civil aviation and airports,[268] the National Infrastructure Agency, in charge of concessions through public–private partnerships, for the design, construction, maintenance, operation, and administration of the transport infrastructure,[269] the General Maritime Directorate (Dimar) has the responsibility of coordinating maritime traffic control along with the Colombian Navy,[270] among others, and under the supervision of the Superintendency of Ports and Transport.[271]

In 2021, Colombia had 204,389 km (127,001 mi) of roads, 32,280 km (20,058 mi) of which were paved. At the end of 2017, the country had around 2,100 km (1,305 mi) of duplicated highways.[272][273][274] Rail transportation in Colombia is dedicated almost entirely to freight shipments and the railway network has a length of 1,700 km of potentially active rails.[274] Colombia has 3,960 kilometers of gas pipelines, 4,900 kilometers of oil pipelines, and 2,990 kilometers of refined-products pipelines.[274]

The Colombian government aimed to build 7,000 km of roads between 2016 and 2020, which would reduce travel times by an estimated 30 per cent, and transport costs by an estimated 20 per cent. A toll road concession programme will comprise 40 projects, and is part of a larger strategic goal to invest nearly $50 bn in transport infrastructure, including railway systems, making the Magdalena River navigable again, improving port facilities, and an expansion of El Dorado International Airport.[275][needs update] Colombia is a middle-income country.[276]

Science and technology

Colombia has more than 3,950 research groups in science and technology.[277] iNNpulsa, a government body that promotes entrepreneurship and innovation in the country, provides grants to startups, in addition to other services it and institutions provide. Colombia was ranked 61st in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[278] Co-working spaces have arisen to serve as communities for startups large and small.[279][280] Organizations such as the Corporation for Biological Research (CIB) for the support of young people interested in scientific work has been successfully developed in Colombia.[281] The International Center for Tropical Agriculture based in Colombia investigates the increasing challenge of global warming and food security.[282]

Important inventions related to medicine have been made in Colombia, such as the first external artificial pacemaker with internal electrodes, invented by the electrical engineer Jorge Reynolds Pombo, an invention of great importance for those who suffer from heart failure. Also invented in Colombia were the microkeratome and keratomileusis technique, which form the fundamental basis of what now is known as LASIK (one of the most important techniques for the correction of refractive errors of vision) and the Hakim valve for the treatment of hydrocephalus.[283] Colombia has begun to innovate in military technology for its army and other armies of the world; especially in the design and creation of personal ballistic protection products, military hardware, military robots, bombs, simulators and radar.[284][285]

Some leading Colombian scientists are Joseph M. Tohme, researcher recognized for his work on the genetic diversity of food, Manuel Elkin Patarroyo who is known for his groundbreaking work on synthetic vaccines for malaria, Francisco Lopera who discovered the "Paisa Mutation" or a type of early-onset Alzheimer's,[286] Rodolfo Llinás known for his study of the intrinsic neurons properties and the theory of a syndrome that had changed the way of understanding the functioning of the brain, Jairo Quiroga Puello recognized for his studies on the characterization of synthetic substances which can be used to fight fungus, tumors, tuberculosis and even some viruses and Ángela Restrepo who established accurate diagnoses and treatments to combat the effects of a disease caused by Paracoccidioides brasiliensis.[287][288][289]

Demographics

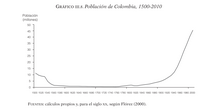

With an estimated 50 million people in 2020, Colombia is the third-most populous country in Latin America, after Brazil and Mexico.[290] At the beginning of the 20th century, Colombia's population was approximately 4 million.[291] Since the early 1970s Colombia has experienced steady declines in its fertility, mortality, and population growth rates. The population growth rate for 2016 is estimated to be 0.9%.[292] About 26.8% of the population were 15 years old or younger, 65.7% were between 15 and 64 years old, and 7.4% were over 65 years old. The proportion of older persons in the total population has begun to increase substantially.[293] Colombia is projected to have a population of 55.3 million by 2050.[294]

Estimates for the population of the area that is now Colombia range between 2.5 and 12 million people in 1500; estimates between the extremes include figures of 6[54] and 7 million. With the Spanish conquest, the region's population had collapsed to around 1.2 million people in 1600, for an estimated decrease of 52–90%. By the end of the colonial period, it had declined further to around 800,000; it began rising in the early 19th century to around 1.4 million, where it would drop again in the Colombian War of Independence to between 1 and 1.2 million. The country's population did not recover to pre-conquest levels until the 1940s, nearly 450 years after its 16th-century peak.[295]

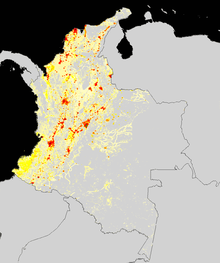

The population is concentrated in the Andean highlands and along the Caribbean coast, also the population densities are generally higher in the Andean region. The nine eastern lowland departments, comprising about 54% of Colombia's area, have less than 6% of the population.[169][170] Traditionally a rural society, movement to urban areas was very heavy in the mid-20th century, and Colombia is now one of the most urbanized countries in Latin America. The urban population increased from 31% of the total in 1938 to nearly 60% in 1973, and by 2014 the figure stood at 76%.[296][297] The population of Bogotá alone has increased from just over 300,000 in 1938 to approximately 8 million today.[298] In total seventy-two cities now have populations of 100,000 or more (2015). As of 2012[update] Colombia has the world's largest populations of internally displaced persons (IDPs), estimated to be up to 4.9 million people.[299]

The life expectancy was 74.8 years in 2015, and infant mortality was 13.1 per thousand in 2016.[300][301] In 2015, 94.58% of adults and 98.66% of youth are literate and the government spends about 4.49% of its GDP on education.[302]

Languages

Around 99.2% of Colombians speak Spanish, also called Castilian; 65 Amerindian languages, two Creole languages, the Romani language and Colombian Sign Language are also used in the country. English has official status in the archipelago of San Andrés, Providencia and Santa Catalina.[11][303][304][305]

Including Spanish, a total of 101 languages are listed for Colombia in the Ethnologue database. The specific number of spoken languages varies slightly since some authors consider as different languages what others consider to be varieties or dialects of the same language. Best estimates recorded 71 languages that are spoken in-country today – most of which belong to the Chibchan, Tucanoan, Bora–Witoto, Guajiboan, Arawakan, Cariban, Barbacoan, and Saliban language families. There are currently more than 850,000 speakers of native languages.[306][307]

Ethnic groups

Ethnic groups in Colombia - 2018 Census[2]

Colombia is ethnically diverse, its people descending from the original Native inhabitants, Spanish conquistadors, Africans originally brought to the country as slaves, and 20th-century immigrants from Europe and the Middle East, all contributing to a diverse cultural heritage.[308] The demographic distribution reflects a pattern that is influenced by colonial history.[309] Whites live all throughout the country, mainly in urban centers and the burgeoning highland and coastal cities. The populations of the major cities also include mestizos. Mestizo campesinos (people living in rural areas) also live in the Andean highlands where some Spanish conquerors mixed with the women of Amerindian chiefdoms. Mestizos include artisans and small tradesmen that have played a major part in the urban expansion of recent decades.[310][2] In a study by the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, Colombians have an average ancestry of 47% Amerindian DNA, 42% European DNA, and 11% African DNA.[311]

The 2018 census reported that the "non-ethnic population", consisting of whites and mestizos (those of mixed European and Amerindian ancestry), constituted 87.6% of the national population. 6.7% is of African ancestry. Indigenous Amerindians constitute 4.3% of the population. Raizal people constitute 0.06% of the population. Palenquero people constitute 0.02% of the population. 0.01% of the population are Roma. A study by Latinobarómetro in 2023 estimates that 50.3% of the population are Mestizo, 26.4% are White, 9.5% are Indigenous, 9.0% are Black, 4.4% are Mulatto, and 0.4% are Asian, these estimates would equate to around 26 million people being Mestizo, 14 million being White, 5 million being Indigenous, 5 million being Black, 2 million being Mulatto, and 200k being Asian.[312]

The Federal Research Division estimated that the 86% of the population that did not consider themselves part of one of the ethnic groups indicated by the 2006 census, white Colombians are mainly of Spanish lineage, but there is also a large population of Middle East descent; in some areas there is a considerable input of German and Italian ancestry.[313][2]

Many of the Indigenous peoples experienced a reduction in population during the Spanish rule[314] and many others were absorbed into the mestizo population, but the remainder currently represents over eighty distinct cultures. Reserves (resguardos) established for indigenous peoples occupy 30,571,640 hectares (305,716.4 km2) (27% of the country's total) and are inhabited by more than 800,000 people.[315] Some of the largest indigenous groups are the Wayuu,[316] the Paez, the Pastos, the Emberá and the Zenú.[317] The departments of La Guajira, Cauca, Nariño, Córdoba and Sucre have the largest indigenous populations.[2]

The Organización Nacional Indígena de Colombia (ONIC), founded at the first National Indigenous Congress in 1982, is an organization representing the indigenous peoples of Colombia. In 1991, Colombia signed and ratified the current international law concerning indigenous peoples, Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989.[318]

Sub-Saharan Africans were brought as slaves, mostly to the coastal lowlands, beginning early in the 16th century and continuing into the 19th century. Large Afro-Colombian communities are found today on the Pacific Coast.[319] Numerous Jamaicans migrated mainly to the islands of San Andres and Providencia. A number of other Europeans and North Americans migrated to the country in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including people from the former USSR during and after the Second World War.[320][321]

Many immigrant communities have settled on the Caribbean coast, in particular recent immigrants from the Middle East and Europe. Barranquilla (the largest city of the Colombian Caribbean) and other Caribbean cities have the largest populations of Lebanese, Palestinian, and other Levantines.[322][323] There are also important communities of Romanis and Jews.[308] There is a major migration trend of Venezuelans, due to the political and economic situation in Venezuela.[324] In August 2019, Colombia offered citizenship to more than 24,000 children of Venezuelan refugees who were born in Colombia.[325]

Religion

The National Administrative Department of Statistics (DANE) does not collect religious statistics, and accurate reports are difficult to obtain. However, based on various studies and a survey, about 90% of the population adheres to Christianity, the majority of which (70.9%–79%) are Roman Catholic, while a significant minority (16.7%) adhere to Protestantism (primarily Evangelicalism). Some 4.7% of the population is atheist or agnostic, while 3.5% claim to believe in God but do not follow a specific religion. 1.8% of Colombians adhere to Jehovah's Witnesses and Adventism and less than 1% adhere to other religions, such as the Baháʼí Faith, Islam, Judaism, Buddhism, Mormonism, Hinduism, Indigenous religions, Hare Krishna movement, Rastafari movement, Eastern Orthodox Church, and spiritual studies. The remaining people either did not respond or replied that they did not know. In addition to the above statistics, 35.9% of Colombians reported that they did not practice their faith actively.[326][327][328] 1,519,562 people in Colombia, or around 3% of the population reported following an Indigenous religion.

While Colombia remains a mostly Roman Catholic country by baptism numbers, the 1991 Colombian constitution guarantees freedom of religion and all religious faiths and churches are equally free before the law.[329]

Health

The overall life expectancy in Colombia at birth is 79.3 years (76.7 years for males and 81.9 years for females).[300] Healthcare reforms have led to massive improvements in the healthcare systems of the country, with health standards in Colombia improving very much since the 1980s. The new system has widened population coverage by the social and health security system from 21% (pre-1993) to 96% in 2012.[331] In 2017, the government declared a cancer research and treatment center as a Project of National Strategic Interest.[332]

A 2016 study conducted by América Economía magazine ranked 21 Colombian health care institutions among the top 44 in Latin America, amounting to 48 percent of the total.[330] In 2022, 26 Colombian hospitals were among the 61 best in Latin America (42% total).[333] Also in 2023, two Colombian hospitals were among the top 75 of the world.[334][335]

Education

The educational experience of many Colombian children begins with attendance at a preschool academy until age five (Educación preescolar). Basic education (Educación básica) is compulsory by law.[336] It has two stages: Primary basic education (Educación básica primaria) which goes from first to fifth grade – children from six to ten years old, and Secondary basic education (Educación básica secundaria), which goes from sixth to ninth grade. Basic education is followed by Middle vocational education (Educación media vocacional) that comprises the tenth and eleventh grades. It may have different vocational training modalities or specialties (academic, technical, business, and so on.) according to the curriculum adopted by each school.[337]

After the successful completion of all the basic and middle education years, a high-school diploma is awarded. The high-school graduate is known as a bachiller, because secondary basic school and middle education are traditionally considered together as a unit called bachillerato (sixth to eleventh grade). Students in their final year of middle education take the ICFES test (now renamed Saber 11) to gain access to higher education (Educación superior). This higher education includes undergraduate professional studies, technical, technological and intermediate professional education, and post-graduate studies. Technical professional institutions of Higher Education are also opened to students holder of a qualification in Arts and Business. This qualification is usually awarded by the SENA after a two years curriculum.[338]

Bachilleres (high-school graduates) may enter into a professional undergraduate career program offered by a university; these programs last up to five years (or less for technical, technological and intermediate professional education, and post-graduate studies), even as much to six to seven years for some careers, such as medicine. In Colombia, there is not an institution such as college; students go directly into a career program at a university or any other educational institution to obtain a professional, technical or technological title. Once graduated from the university, people are granted a (professional, technical or technological) diploma and licensed (if required) to practice the career they have chosen. For some professional career programs, students are required to take the Saber-Pro test, in their final year of undergraduate academic education.[337]

Public spending on education as a proportion of gross domestic product in 2015 was 4.49%. This represented 15.05% of total government expenditure. The primary and secondary gross enrolment ratios stood at 113.56% and 98.09% respectively. School-life expectancy was 14.42 years. A total of 94.58% of the population aged 15 and older were recorded as literate, including 98.66% of those aged 15–24.[302]

Crime

Colombia has a high crime rate due to being a center for the cultivation and trafficking of cocaine. The Colombian conflict began in the mid-1960s and is a low-intensity conflict between Colombian governments, paramilitary groups, crime syndicates, and left-wing guerrillas such as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), and the National Liberation Army (ELN), fighting each other to increase their influence in Colombian territory. Two of the most important international actors that have contributed to the Colombian conflict are multinational companies and the United States.[339][340][341]

Elements of all the armed groups have been involved in drug trafficking. In a country where state capacity has been weak in some regions, the result has been a grinding war on multiple fronts, with the civilian population caught in between and often deliberately targeted for "collaborating". Human rights advocates blame paramilitaries for massacres, "disappearances", and cases of torture and forced displacement. Rebel groups are behind assassinations, kidnapping and extortion.[342]

In 2011, President Juan Manuel Santos launched the "Borders for Prosperity" plan[343] to fight poverty and combat violence from illegal armed groups along Colombia's borders through social and economic development.[344] The plan received praise from the International Crisis Group.[345] Colombia registered a homicide rate of 24.4 per 100,000 in 2016, the lowest since 1974. The 40-year low in murders came the same year the government signed a peace agreement with the FARC.[346] The murder rate further decreased to 22.6 in 2020, though still among the highest in the world, it decreased 73% from 84 in 1991. In the 1980s and 1990s it regularly ranked as number one.

Since the beginning of the crisis in Venezuela and the mass emigration of Venezuelans during the Venezuelan refugee crisis, desperate Venezuelans have been recruited into gangs in order to survive by other Venezuelan gang members.[347] Venezuelan women have also resorted to prostitution in order to make a living in Colombia.[347] Also, many Venezuelan prisoners were released from Venezuelan prisons by Maduro. Gang groups from Venezuela have also migrated to Colombia and other countries.Urbanization

Colombia is a highly urbanized country with 77.1% of the population living in urban areas. The largest cities in the country are Bogotá, with 7,387,400 inhabitants, Medellín, with 2,382,399 inhabitants, Cali, with 2,172,527 inhabitants, and Barranquilla, with 1,205,284 inhabitants.[348]

| Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | Rank | Name | Department | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Bogotá  Medellín |

1 | Bogotá | Distrito Capital | 7,387,400 | 11 | Ibagué | Tolima | 492,554 |  Cali |

| 2 | Medellín | Antioquia | 2,382,399 | 12 | Villavicencio | Meta | 492,052 | ||

| 3 | Cali | Valle del Cauca | 2,172,527 | 13 | Santa Marta | Magdalena | 455,299 | ||

| 4 | Barranquilla | Atlántico | 1,205,284 | 14 | Valledupar | Cesar | 431,794 | ||

| 5 | Cartagena | Bolívar | 876,885 | 15 | Manizales | Caldas | 405,234 | ||

| 6 | Cúcuta | Norte de Santander | 685,445 | 16 | Montería | Córdoba | 388,499 | ||

| 7 | Soacha | Cundinamarca | 655,025 | 17 | Pereira | Risaralda | 385,838 | ||

| 8 | Soledad | Atlántico | 602,644 | 18 | Neiva | Huila | 335,994 | ||

| 9 | Bucaramanga | Santander | 570,752 | 19 | Pasto | Nariño | 308,095 | ||

| 10 | Bello | Antioquia | 495,483 | 20 | Armenia | Quindío | 287,245 | ||

Culture

Colombia lies at the crossroads of Latin America and the broader American continent, and as such has been hit by a wide range of cultural influences. Native American, Spanish and other European, African, American, Caribbean, and Middle Eastern influences, as well as other Latin American cultural influences, are all present in Colombia's modern culture. Urban migration, industrialization, globalization, and other political, social and economic changes have also left an impression.[citation needed]

Many national symbols, both objects and themes, have arisen from Colombia's diverse cultural traditions and aim to represent what Colombia, and the Colombian people, have in common. Cultural expressions in Colombia are promoted by the government through the Ministry of Culture.[350]

Literature

Colombian literature dates back to pre-Columbian era; a notable example of the period is the epic poem known as the Legend of Yurupary.[352] In Spanish colonial times, notable writers include Juan de Castellanos (Elegías de varones ilustres de Indias), Hernando Domínguez Camargo and his epic poem to San Ignacio de Loyola, Pedro Simón and Juan Rodríguez Freyle.[353]

Post-independence literature linked to Romanticism highlighted Antonio Nariño, José Fernández Madrid, Camilo Torres Tenorio and Francisco Antonio Zea.[354][355] In the second half of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century the literary genre known as costumbrismo became popular; great writers of this period were Tomás Carrasquilla, Jorge Isaacs and Rafael Pombo (the latter of whom wrote notable works of children's literature).[356][357] Within that period, authors such as José Asunción Silva, José Eustasio Rivera, León de Greiff, Porfirio Barba-Jacob and José María Vargas Vila developed the modernist movement.[358][359][360] In 1872, Colombia established the Colombian Academy of Language, the first Spanish language academy in the Americas.[361] Candelario Obeso wrote the groundbreaking Cantos Populares de mi Tierra (1877), the first book of poetry by an Afro-Colombian author.[362][363]

Between 1939 and 1940 seven books of poetry were published under the name Stone and Sky in the city of Bogotá that significantly influenced the country; they were edited by the poet Jorge Rojas.[364] In the following decade, Gonzalo Arango founded the movement of "nothingness" in response to the violence of the time;[365] he was influenced by nihilism, existentialism, and the thought of another great Colombian writer: Fernando González Ochoa.[366] During the boom in Latin American literature, successful writers emerged, led by Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez and his magnum opus, One Hundred Years of Solitude, Eduardo Caballero Calderón, Manuel Mejía Vallejo, and Álvaro Mutis, a writer who was awarded the Cervantes Prize and the Prince of Asturias Award for Letters.[367][368]

Visual arts

Colombian art has over 3,000 years of history. Colombian artists have captured the country's changing political and cultural backdrop using a range of styles and mediums. There is archeological evidence of ceramics being produced earlier in Colombia than anywhere else in the Americas, dating as early as 3,000 BCE.[371][372]

The earliest examples of gold craftsmanship have been attributed to the Tumaco people[373] of the Pacific coast and date to around 325 BCE. Roughly between 200 BCE and 800 CE, the San Agustín culture, masters of stonecutting, entered its "classical period". They erected raised ceremonial centers, sarcophagi, and large stone monoliths depicting anthropomorphic and zoomorphic forms out of stone.[372][374]

Colombian art has followed the trends of the time, so during the 16th to 18th centuries, Spanish Catholicism had a huge influence on Colombian art, and the popular baroque style was replaced with rococo when the Bourbons ascended to the Spanish crown.[375][376] During this era, in the Spanish colony, the most important Neogranadine (Colombian) painters were Gregorio Vásquez de Arce y Ceballos, Gaspar de Figueroa, Baltasar Vargas de Figueroa, Baltasar de Figueroa (the Elder), Antonio Acero de la Cruz and Joaquín Gutiérrez, of which their works are preserved. Also important was Alonso de Narváez who, although born in the Province of Seville, spent most of his life in colonial Colombia, also the Italian Angelino Medoro, lived in Colombia and Peru, and left works of art preserved in several churches in Tunja city.

During the mid-19th century, one of the most remarkable painters was Ramón Torres Méndez, who produced a series of good quality paintings depicting the people and their customs of different Colombian regions. Also noteworthy in the 19th century were Andrés de Santa María, Pedro José Figueroa, Epifanio Garay, Mercedes Delgado Mallarino, José María Espinosa, Ricardo Acevedo Bernal, between many others.

More recently, Colombian artists Pedro Nel Gómez and Santiago Martínez Delgado started the Colombian Murial Movement in the 1940s, featuring the neoclassical features of Art Deco.[371][372][377][378] Since the 1950s, the Colombian art started to have a distinctive point of view, reinventing traditional elements under the concepts of the 20th century. Examples of this are the Greiff portraits by Ignacio Gómez Jaramillo, showing what the Colombian art could do with the new techniques applied to typical Colombian themes. Carlos Correa, with his paradigmatic "Naturaleza muerta en silencio" (silent dead nature), combines geometrical abstraction and cubism. Alejandro Obregón is often considered as the father of modern Colombian painting, and one of the most influential artist in this period, due to his originality, the painting of Colombian landscapes with symbolic and expressionist use of animals, (specially the Andean condor).[372][379][380] Fernando Botero, Omar Rayo, Enrique Grau, Édgar Negret, David Manzur, Rodrigo Arenas Betancourt, Oscar Murillo, Doris Salcedo and Oscar Muñoz are some of the Colombian artists featured at the international level.[371][381][382][383]

The Colombian sculpture from the sixteenth to 18th centuries was mostly devoted to religious depictions of ecclesiastic art, strongly influenced by the Spanish schools of sacred sculpture. During the early period of the Colombian republic, the national artists were focused in the production of sculptural portraits of politicians and public figures, in a plain neoclassicist trend.[384] During the 20th century, the Colombian sculpture began to develop a bold and innovative work with the aim of reaching a better understanding of national sensitivity.[372][385]

Colombian photography was marked by the arrival of the daguerreotype. Jean-Baptiste Louis Gros was who brought the daguerreotype process to Colombia in 1841. The Piloto public library has Latin America's largest archive of negatives, containing 1.7 million antique photographs covering Colombia 1848 until 2005.[386][387]

The Colombian press has promoted the work of the cartoonists. In recent decades, fanzines, internet and independent publishers have been fundamental to the growth of the comic in Colombia.[388][389][390]

Architecture

Throughout the times, there have been a variety of architectural styles, from those of indigenous peoples to contemporary ones, passing through colonial (military and religious), Republican, transition and modern styles.[391]

Ancient habitation areas, longhouses, crop terraces, roads as the Inca road system, cemeteries, hypogeums and necropolises are all part of the architectural heritage of indigenous peoples.[392] Some prominent indigenous structures are the preceramic and ceramic archaeological site of Tequendama,[393] Tierradentro (a park that contains the largest concentration of pre-Columbian monumental shaft tombs with side chambers),[394] the largest collection of religious monuments and megalithic sculptures in South America, located in San Agustín, Huila,[374][395] Lost city (an archaeological site with a series of terraces carved into the mountainside, a net of tiled roads, and several circular plazas), and the large villages mainly built with stone, wood, cane, and mud.[396] Architecture during the period of conquest and colonization is mainly derived of adapting European styles to local conditions, and Spanish influence, especially Andalusian and Extremaduran, can be easily seen.[397] When Europeans founded cities two things were making simultaneously: the dimensioning of geometrical space (town square, street), and the location of a tangible point of orientation.[398] The construction of forts was common throughout the Caribbean and in some cities of the interior, because of the dangers posed to Spanish colonial settlements from English, French and Dutch pirates and hostile indigenous groups.[399] Churches, chapels, schools, and hospitals belonging to religious orders have a great urban influence.[400] Baroque architecture is used in military buildings and public spaces.[401] Marcelino Arroyo, Francisco José de Caldas and Domingo de Petrés were great representatives of neo-classical architecture.[400]

The National Capitol is a great representative of romanticism.[402] Wood was extensively used in doors, windows, railings, and ceilings during the colonization of Antioquia. The Caribbean architecture acquires a strong Arabic influence.[403] The Teatro Colón in Bogotá is a lavish example of architecture from the 19th century.[404] The quintas houses with innovations in the volumetric conception are some of the best examples of the Republican architecture; the Republican action in the city focused on the design of three types of spaces: parks with forests, small urban parks and avenues and the Gothic style was most commonly used for the design of churches.[405]

Deco style, modern neoclassicism, eclecticism folklorist and art deco ornamental resources significantly influenced the architecture of Colombia, especially during the transition period.[406] Modernism contributed with new construction technologies and new materials (steel, reinforced concrete, glass and synthetic materials) and the topology architecture and lightened slabs system also have a great influence.[407] The most influential architects of the modern movement were Rogelio Salmona and Fernando Martínez Sanabria.[408]

The contemporary architecture of Colombia is designed to give greater importance to the materials, this architecture takes into account the specific natural and artificial geographies and is also an architecture that appeals to the senses.[409] The conservation of the architectural and urban heritage of Colombia has been promoted in recent years.[410]

Music

Colombia has a vibrant collage of talent that touches a full spectrum of rhythms. It is known as the land of a thousand rhythms, at around 1,024 folk rhythms. Musicians, composers, music producers and singers from Colombia are recognized internationally such as Shakira, Juanes, Carlos Vives and others.[411] Colombian music blends European-influenced guitar and song structure with large gaita flutes and percussion instruments from the indigenous population, while its percussion structure and dance forms come from Africa. Colombia has a diverse and dynamic musical environment.[412]

Guillermo Uribe Holguín, an important cultural figure in the National Symphony Orchestra of Colombia, Luis Antonio Calvo and Blas Emilio Atehortúa are some of the greatest exponents of the art music.[413] The Bogotá Philharmonic Orchestra is one of the most active orchestras in Colombia.[414]

Caribbean music has many vibrant rhythms, such as cumbia (it is played by the maracas, the drums, the gaitas and guacharaca), porro (it is a monotonous but joyful rhythm), mapalé (with its fast rhythm and constant clapping) and the "vallenato", which originated in the northern part of the Caribbean coast (the rhythm is mainly played by the caja, the guacharaca, and accordion).[415][416][417][418][419]

The music from the Pacific coast, such as the currulao, is characterized by its strong use of drums (instruments such as the native marimba, the conunos, the bass drum, the side drum, and the cuatro guasas or tubular rattle). An important rhythm of the south region of the Pacific coast is the contradanza (it is used in dance shows due to the striking colours of the costumes).[415][420][421] Marimba music, traditional chants and dances from the Colombia South Pacific region are on UNESCO's Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.[422][423][424]