STS-3xx

| Mission type | Crew rescue |

|---|---|

| Mission duration | 4 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft type | Space Shuttle |

| Crew | |

| Crew size | 4 |

| Members | None assigned |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | Flight Day 45 Relative to original mission |

| Launch site | Kennedy LC-39 |

| End of mission | |

| Landing date | Flight Day 49 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

| Inclination | 51.6 degrees |

| Docking with ISS | |

| Docking date | Flight Day 47 |

| Undocking date | Flight Day 48 |

| Time docked | < 1 day |

Space Shuttle missions designated STS-3xx (officially called Launch On Need (LON) missions) were rescue missions which would have been mounted to rescue the crew of a Space Shuttle if their vehicle was damaged and deemed unable to make a successful reentry. Such a mission would have been flown if Mission Control determined that the heat shielding tiles and reinforced carbon-carbon panels of a currently flying orbiter were damaged beyond the repair capabilities of the available on-orbit repair methods. These missions were also referred to as Launch on Demand (LOD) and Contingency Shuttle Crew Support. The program was initiated following loss of Space Shuttle Columbia in 2003. No mission of this type was launched during the Space Shuttle program.

Procedure

[edit]The orbiter and four of the crew which were due to fly the next planned mission would be retasked to the rescue mission. The planning and training processes for a rescue flight would allow NASA to launch the mission within a period of 40 days of its being called up. During that time the damaged (or disabled) shuttle's crew would have to take refuge on the International Space Station (ISS). The ISS is able to support both crews for around 80 days, with oxygen supply being the limiting factor.[1] Within NASA, this plan for maintaining the shuttle crew at the ISS is known as Contingency Shuttle Crew Support (CSCS) operations.[2] Up to STS-121 all rescue missions were to be designated STS-300.

In the case of an abort to orbit, where the shuttle could have been unable to reach the ISS orbit and the thermal protection system inspections suggested that the shuttle could not have returned to Earth safely, the ISS may have been capable of descending to meet the shuttle. Such a procedure was known as a joint underspeed recovery.[3]

| Flight | Rescue flight[2][4][5][6] |

|---|---|

| STS-114 (Discovery) | STS-300 (Atlantis) |

| STS-121 (Discovery) | STS-300 (Atlantis) |

| STS-115 (Atlantis) | STS-301 (Discovery) |

| STS-116 (Discovery) | STS-317 (Atlantis) |

| STS-117 (Atlantis) | STS-318 (Endeavour[citation needed]) |

| STS-118 (Endeavour) | STS-322 (Discovery) |

| STS-120 (Discovery) | STS-320 (Atlantis) |

| STS-122 (Atlantis) | STS-323 (Discovery*)[7] |

| STS-123 (Endeavour) | STS-324 (Discovery) |

| STS-124 (Discovery) | STS-326 (Endeavour) |

| STS-125 (Atlantis) | STS-400 (Endeavour) |

| STS-134 (Endeavour) | STS-335 (Atlantis) |

* – originally scheduled to be Endeavour, changed to Discovery for contamination issues.[7]

To save weight, and to allow the combined crews of both shuttles to return to Earth safely, many shortcuts would have to be made, and the risks of launching another orbiter without resolving the failure which caused the previous orbiter to become disabled would have to be faced.

Flight hardware

[edit]A number of pieces of Launch on Need flight hardware were built in preparation for a rescue mission including:

- An extra three recumbent seats to be located in the aft middeck (ditch area)

- Two handholds located on the starboard wall of the ditch area

- Individual Cooling Units mounting provisions

- Seat 5 modification to properly secure in a recumbent position

- Mounting provisions for four additional Sky Genie egress devices (see picture)

Training with a Sky Genie egress device - Escape Pole mounting provisions for three additional lanyards[8]

Remote Control Orbiter

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (February 2013) |

The Remote Control Orbiter (RCO), also known as the Autonomous Orbiter Rapid Prototype (AORP), was a term used by NASA to describe a shuttle that could perform entry and landing without a human crew on board via remote control. NASA developed the RCO in-flight maintenance (IFM) cable to extend existing auto-land capabilities of the shuttle to allow remaining tasks to be completed from the ground. The purpose of the RCO IFM cable was to provide an electrical signal connection between the Ground Command Interface Logic (GCIL) and the flight deck panel switches. The cable is approximately 28 feet (8.5 m) long, weighs over 5 lb (2.3 kg), and has 16 connectors.[9][10] With this system, signals could be sent from the Mission Control Center to the unmanned shuttle to control the following systems:

- Auxiliary Power Unit (APU) start and run

- Air Data Probe (ADP) deployment

- Main Landing Gear (MLG) arming and deployment

- Drag chute arming and deployment

- Fuel cell reactant valve closure

The RCO IFM cable first flew aboard STS-121 and was transferred to the ISS for storage during the mission. The cable remained aboard the ISS until the end of the Shuttle program. Prior to STS-121 the plan was for the damaged shuttle to be abandoned and allowed to burn up on reentry. The prime landing site for an RCO orbiter would be Vandenberg Air Force Base in California.[11] Edwards Air Force Base, a site already used to support shuttle landings, was the prime RCO landing site for the first missions carrying the equipment; however Vandenberg was later selected as the prime site as it is nearer the coast, and the shuttle can be ditched in the Pacific should a problem develop that would make landing dangerous. White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico is a likely alternate site.[12] A major consideration in determining the landing site would be the desire to perform a high-risk re-entry far away from populated areas. The flight resource book, and flight rules in force during STS-121 suggest that the damaged shuttle would reenter on a trajectory such that if it should break up, it would do so with debris landing in the South Pacific Ocean.[2]

The Soviet Buran shuttle was also remotely controlled during its entire maiden flight without a crew aboard. Landing was carried out by an onboard, automatic system.[13]

As of March 2011 the Boeing X-37 extended duration robotic spaceplane has demonstrated autonomous orbital flight, reentry and landing.[14][15] The X-37 was originally intended for launch from the Shuttle payload bay, but following the Columbia disaster, it was launched in a shrouded configuration on an Atlas V.

Sample timeline

[edit]Had a LON mission been required, a timeline would have been developed similar to the following:

- FD-10 A decision on the requirement for Contingency Shuttle Crew Support (CSCS) is expected by flight day 10 of a nominal mission.

- FD-10 Shortly after the need for CSCS operations a group C powerdown of the shuttle will take place.

- FD-11→21 During flight days 11–21 of the mission the shuttle will remain docked to the international space station (ISS) with the hatch open. Various items will be transferred between the shuttle and ISS.

- FD-21 Hatch closure will be conducted from the ISS side. The shuttle crew remains on the ISS, leaving the shuttle unmanned

- FD-21 Deorbit burn – burn occurs four hours after separation. Orbiter lands at Vandenberg Air Force Base under remote control from Houston. (Prior to STS-121, the payload bay doors would have been left open to promote vehicle breakup.)

- FD-45 Launch of rescue flight. 35 days from call-up to launch for the rescue flight is a best estimate of the minimum time it will take before a rescue flight is launched.[16]

- FD-45→47 The rescue flight catches up with the ISS, conducting heat shield inspections en route.

- FD-47 The rescue flight docks with the station, on day three of its mission.

- FD-48 Shuttle crew enters the rescue orbiter. Vehicle with a crew complement of 11 undocks from ISS.

- FD-49 Rescue orbiter re-enters atmosphere over Indian or Pacific Ocean for landing at either Kennedy Space Center or Edwards Air Force Base. A Russian Progress resupply spacecraft is launched at later date to resupply ISS crew. ISS precautionary de-crew preparations begin.

- FD-58 De-crew ISS due to ECLSS O2 exhaustion in event Progress unable to perform resupply function.

STS-125 rescue plan

[edit]| Mission type | Crew rescue |

|---|---|

| Mission duration | 7 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Space Shuttle Endeavour |

| Crew | |

| Crew size |

|

| Members | |

| Landing | |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric |

| Regime | Low Earth |

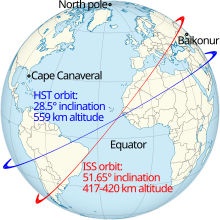

| Inclination | 28.5 degrees |

STS-400 was the Space Shuttle contingency support (Launch On Need) flight that would have been launched using Space Shuttle Endeavour if a major problem occurred on Space Shuttle Atlantis during STS-125, the final Hubble Space Telescope servicing mission (HST SM-4).[17][18][19][20]

Due to the much lower orbital inclination of the HST compared to the ISS, the shuttle crew would have been unable to use the International Space Station as a "safe haven", and NASA would not have been able to follow the usual plan of recovering the crew with another shuttle at a later date.[19] Instead, NASA developed a plan to conduct a shuttle-to-shuttle rescue mission, similar to proposed rescue missions for pre-ISS flights.[19][21][22] The rescue mission would have been launched only three days after call-up and as early as seven days after the launch of STS-125, since the crew of Atlantis would only have about three weeks of consumables after launch.[18]

The mission was first rolled out in September 2008 to Launch Complex 39B two weeks after the STS-125 shuttle was rolled out to Launch Complex 39A, creating a rare scenario in which two shuttles were on launch pads at the same time.[19] In October 2008, however, STS-125 was delayed and rolled back to the VAB.

Initially, STS-125 was retargeted for no earlier than February 2009. This changed the STS-400 vehicle from Endeavour to Discovery. The mission was redesignated STS-401 due to the swap from Endeavour to Discovery. STS-125 was then delayed further, allowing Discovery mission STS-119 to fly beforehand. This resulted in the rescue mission reverting to Endeavour, and the STS-400 designation being reinstated.[20] In January, 2009, it was announced that NASA was evaluating conducting both launches from Complex 39A in order to avoid further delays to Ares I-X, which, at the time, was scheduled for launch from LC-39B in the September 2009 timeframe.[20] It was planned that after the STS-125 mission in October 2008, Launch Complex 39B would undergo the conversion for use in Project Constellation for the Ares I-X rocket.[20] Several of the members on the NASA mission management team said at the time (2009) that single-pad operations were possible, but the decision was made to use both pads.[18][19]

Crew

[edit]The crew assigned to this mission was a subset of the STS-126 crew:[18][23]

| Position | Launching Astronaut | Landing Astronaut |

|---|---|---|

| Commander | Christopher Ferguson | |

| Pilot | Eric A. Boe | |

| Mission Specialist 1 | Robert S. Kimbrough | |

| Mission Specialist 2 | Stephen G. Bowen | |

| STS-125 Commander | None | Scott D. Altman |

| STS-125 Pilot | None | Gregory C. Johnson |

| STS-125 Mission Specialist 1 |

None | Michael T. Good |

| STS-125 Mission Specialist 2 |

None | Megan McArthur |

| STS-125 Mission Specialist 3 |

None | John M. Grunsfeld |

| STS-125 Mission Specialist 4 |

None | Michael J. Massimino |

| STS-125 Mission Specialist 5 |

None | Andrew J. Feustel |

Early mission plans

[edit]

Three different concept mission plans were evaluated: The first would be to use a shuttle-to-shuttle docking, where the rescue shuttle docks with the damaged shuttle, by flying upside down and backwards, relative to the damaged shuttle.[22] It was unclear whether this would be practical, as the forward structure of either orbiter could collide with the payload bay of the other, resulting in damage to both orbiters. The second option that was evaluated, would be for the rescue orbiter to rendezvous with the damaged orbiter, and perform station-keeping while using its Remote Manipulator System (RMS) to transfer crew from the damaged orbiter. This mission plan would result in heavy fuel consumption. The third concept would be for the damaged orbiter to grapple the rescue orbiter using its RMS, eliminating the need for station-keeping.[23] The rescue orbiter would then transfer crew using its RMS, as in the second option, and would be more fuel efficient than the station-keeping option.[22]

The concept that was eventually decided upon was a modified version of the third concept. The rescue orbiter would use its RMS to grapple the end of the damaged orbiter's RMS.[17][24]

Preparations

[edit]

After its most recent mission (STS-123), Endeavour was taken to the Orbiter Processing Facility for routine maintenance. Following the maintenance, Endeavour was on stand-by for STS-326 which would have been flown in the case that STS-124 would not have been able to return to Earth safely. Stacking of the solid rocket boosters (SRB) began on 11 July 2008. One month later, the external tank arrived at KSC and was mated with the SRBs on 29 August 2008. Endeavour joined the stack on 12 September 2008 and was rolled out to Pad 39B one week later.

Since STS-126 launched before STS-125, Atlantis was rolled back to the VAB on 20 October, and Endeavour rolled around to Launch Pad 39A on 23 October. When it was time to launch STS-125, Atlantis rolled out to pad 39A.[20]

Mission plan

[edit]The Mission would not have included the extended heatshield inspection normally performed on flight day two.[17][19] Instead, an inspection would have been performed after the crew was rescued.[17][19] On flight day two, Endeavour would have performed the rendezvous and grapple with Atlantis.[17][23] On flight day three, the first EVA would have been performed.[17][19][23] During the first EVA, Megan McArthur, Andrew Feustel and John Grunsfeld would have set up a tether between the airlocks.[18][19] They would have also transferred a large size Extravehicular Mobility Unit (EMU) and, after McArthur had repressurized, transferred McArthur's EMU back to Atlantis. Afterwards they would have repressurized on Endeavour, ending flight day two activities.[17]

The final two EVA were planned for flight day three.[17][19] During the first, Grunsfeld would have depressurized on Endeavour in order to assist Gregory Johnson and Michael Massimino in transferring an EMU to Atlantis. He and Johnson would then repressurize on Endeavour, and Massimino would have gone back to Atlantis.[17] He, along with Scott Altman and Michael Good would have taken the rest of the equipment and themselves to Endeavour during the final EVA. They would have been standing by in case the RMS system should malfunction.[24] The damaged orbiter would have been commanded by the ground to deorbit and go through landing procedures over the Pacific, with the impact area being north of Hawaii.[18][19] On flight day five, Endeavour would have had a full heat shield inspection, and land on flight day eight.[17][18][19]

This mission could have marked the end of the Space Shuttle program, as it is considered unlikely that the program would have been able to continue with just two remaining orbiters, Discovery and Endeavour.[25]

On Thursday, 21 May 2009, NASA officially released Endeavour from the rescue mission, freeing the orbiter to begin processing for STS-127. This also allowed NASA to continue processing LC-39B for the upcoming Ares I-X launch, as during the stand-down period, NASA installed a new lightning protection system, similar to those found on the Atlas V and Delta IV pads, to protect the newer, taller Ares I rocket from lightning strikes.[26][27]

STS-335

[edit]STS-134 was the last scheduled flight of the Shuttle program. Because no more were planned after this, a special mission was developed as STS-335 to act as the LON mission for this flight. This would have paired Atlantis with ET-122, which had been refurbished following damage by Hurricane Katrina.[28] Since there would be no next mission, STS-335 would also carry a Multi-Purpose Logistics Module filled with supplies to replenish the station.[29]

The Senate authorized STS-135 as a regular flight on 5 August 2010,[30] followed by the House on 29 September 2010,[31] and later signed by President Obama on 11 October 2010.[32] However funding for the mission remained dependent on a subsequent appropriations bill.

Nonetheless NASA converted STS-335, the final Launch On Need mission, into an operational mission (STS-135) on 20 January 2011.[33] On 13 February 2011, program managers told their workforce that STS-135 would fly "regardless" of the funding situation via a continuing resolution.[34] Finally the U.S. government budget approved in mid-April 2011 called for $5.5 billion for NASA's space operations division, including the Space Shuttle and space station programs. According to NASA, the budget running through 30 September 2011 ended all concerns about funding the STS-135 mission.[35]

With the successful completion of STS-134, STS-335 was rendered unnecessary and launch preparations for STS-135 continued as Atlantis neared LC-39A during its rollout as STS-134 landed at the nearby Shuttle Landing Facility.[36]

For STS-135, no shuttle was available for a rescue mission. A different rescue plan was devised, involving the four crew members remaining aboard the International Space Station, and returning aboard Soyuz spacecraft one at a time over the next year. That contingency was not required.

References

[edit]- ^ "Flight Readiness Review Briefing, Transcript of press briefing carried on NASA TV" (PDF). NASA. 17 June 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2006.

- ^ a b c "Contingency Shuttle Crew Support (CSCS)/Rescue Flight Resource Book" (PDF). NASA. 12 July 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 March 2016. Retrieved 31 July 2006.

- ^ Engineering for Complex Systems Knowledge Engineering for Safety and Success Project[dead link]

- ^ "STS-121 Nasa Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. May 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2006.

- ^ "NASA Launch Schedule" (PDF). NASA Via Hipstersunite.com. 2 November 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2007.

- ^ Nasa Assurance Technology Center News Article Archived 2 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Bergin, Chris (7 February 2008). "STS-122: Atlantis launches – Endeavour LON doubt". NASAspaceflight.com.

- ^ "STS-114 Flight Readiness Review Presentation" (PDF). NASA. 29 June 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2006.

- ^ Kestenbaum, David (29 June 2006). "Emergency Rescue Plans in Place for Astronauts". NPR. Retrieved 19 September 2006.

- ^ USA Master Template - Revised

- ^ Bergin, Chris (7 August 2006). "NASA enhancing unmanned orbiter capability". NASASpaceflight.com.

- ^ Malik, Tariq (29 June 2006). "Shuttle to Carry Tools for Repair and Remote-Control Landing". Space.com.

- ^ Karimov, A.G. (1997). "Control of Onboard Complex of Equipment". In Lozino-Lozinsky, G.E.; Bratukhin., A.G. (eds.). Aerospace Systems: Book of Technical Papers (ZIP MSWORD). Moscow: Publishing House of Moscow Aviation Institute. p. 206. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

The structure is built with allowance for three possible Orbiter's control modes: automatic, manual and under commands from the ground-based control complex (GBCC).

- ^ "X-37B Orbital Test Vehicle". Office of the Secretary of the Air Force (Public Affairs). Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ "X-37 Demonstrator to Test Future Launch Technologies in Orbit and Reentry Environments". NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. May 2003. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ^ Contingency Shuttle Crew Support (CSCS)/Rescue Flight Resource Book. 12 July 2005 Archived 1 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine p. 101

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j NASA Mission Operations Directorate (2 June 2008). "STS-400 Flight Plan" (PDF). NASA. Retrieved 19 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g NASA (5 May 2009). "STS-400: Ready and Waiting". NASA. Archived from the original on 17 September 2011. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Atkinson, Nancy (17 April 2009). "The STS-400 Shuttle Rescue Mission Scenario". Universe Today. Retrieved 18 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Bergin, Chris (19 January 2009). "STS-125/400 Single Pad option progress – aim to protect Ares I-X". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (9 May 2006). "Hubble Servicing Mission moves up". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- ^ a b c Copella, John (31 July 2007). "NASA Evaluates Rescue Options for Hubble Mission". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- ^ a b c d NASA (9 September 2008). "STS-125 Mission Overview Briefing Materials". NASA. Retrieved 17 May 2009.

- ^ a b Bergin, Chris (11 October 2007). "STS-400 – NASA draws up their Hubble rescue plans". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 16 October 2007.

- ^ Watson, Traci (22 March 2005). "The mission NASA hopes won't happen". USA Today. Retrieved 13 September 2006.

- ^ Harwood, William (21 May 2009). "Iffy weather forecast for Friday's shuttle landing". CBS News, Spaceflightnow.com. Retrieved 22 May 2009.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (22 May 2009). "Endeavour in STS-127 flow". NASA Spaceflight.com. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (26 April 2009). "Downstream processing and planning – preparing the fleet through to STS-135". NASASpaceflight.com. Retrieved 14 June 2009.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (13 October 2009). "NASA Evaluate STS-335/STS-133 Cross Country Farewell". NASASpaceflight.com.

- ^ Clark, Stephen (6 August 2010). "Senate approves bill adding extra space shuttle flight". Spaceflight Now Inc.

- ^ Abrams, Jim (30 September 2010). "NASA bill passed by Congress would allow for one additional shuttle flight in 2011". ABC Action News. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011.

- ^ Amos, Jonathan (11 October 2010). "Obama signs Nasa up to new future". BBC News.

- ^ "Dean, James "Atlantis officially named final shuttle mission" (23 January 2010) Florida Today". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ^ NASA managers insist STS-135 will fly – Payload options under assessment NASASpaceFlight.com

- ^ Clark, Stephen (21 April 2011). "Federal budget pays for summer shuttle flight". Spaceflight Now. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- ^ Endeavour arrives home one final time to conclude STS-134 | NASASpaceFlight.com

External links

[edit]- "CSCS Flight Rules" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2006. (34.2 KiB)