Regino of Prüm

Regino of Prüm or of Prum (Latin: Regino Prumiensis, German: Regino von Prüm; died 915 AD) was a Benedictine monk, who served as abbot of Prüm (892–99) and later of Saint Martin's at Trier, and chronicler, whose Chronicon is an important source for late Carolingian history.

Biography

[edit]According to the statements of a later era, Regino was the son of noble parents and was born at the stronghold of Altrip on the Rhine near Speyer at an unknown date. From his election as abbot and from his writings, it is evident that he had entered the Benedictine Order, probably at Prüm itself, and that he had been a diligent student. The rich and celebrated Imperial Abbey of Prüm suffered greatly during the 9th century from the marauding incursions of the Norsemen. It had been twice seized and ravaged, in 882 AD and 892 AD. After its second devastation by the Danes, the abbot Farabert resigned his office and Regino was elected his successor in 892 AD. His labours for the restoration of the devastated abbey were hampered by the struggle between contending parties in Lorraine.

In 899 AD Regino was driven from his office by Richarius, later Bishop of Liège, the brother of Count Gerhard and count Mattfried of Hainaut. Richarius was made abbot; Regino had lost the position and relocated to Trier, where he was honourably received by Archbishop Ratbod and was appointed abbot of St Martin's, a house which he later reformed. He supported the archbishop in the latter's efforts to carry out ecclesiastical reforms in that troubled era, rebuilt the Abbey of St. Martin that had been laid waste by the Norsemen, accompanied the archbishop on visitations, and used his leisure for writing. Regino died at Trier in 915 AD and was buried in St. Maximin's Abbey, Trier, his tomb being discovered there in 1581.

Works

[edit]Regino's works are edited in volume 132 of Migne's Patrologia Latina.

De harmonica institutione and Tonarius

[edit]Regino's earliest work was Epistola de harmonica institutione, a treatise on music which he wrote in the form of a letter to Archbishop Radbod. Its primary objective was to improve the liturgical singing in the churches of the diocese and probably to ensure Radbod's support for this. He also wrote the Tonarius, a collection of chants.[1]

Chronicon

[edit]Regino's most influential work is his Chronicon, a universal history from the Incarnation of Jesus Christ to 906 AD. The Chronicon's focus is a history of the Carolingian empire that connected the rise and fall of the Carolingian dynasty with his own affairs.[2] The work's intended recipient is unknown, but may have been Louis the Child (r. 900–911), and was dedicated to Adalberon, bishop of Augsburg (†909), someone personally close to the child king.[citation needed] The Chronicon was later continued from 906 until 967 (known as the Continuatio Reginonis), and edited by a certain Adalbert, a monk at the Benedictine monastery of Saint Maximinus in Trier, possibly Adalbert, Archbishop of Magdeburg.[citation needed]

The first book contains broad narratives on the fortunes of various rulers and church men, which are organised against the regnal spans of Roman and Byzantine emperors, and ends in the year 741 with the death of Charles Martel. It consists of extracts taken from Bede, Paulus Diaconus, the Deeds of Dagobert, the Annals of Saint-Amand and the chronicle Liber Historiae Francorum. Of the second book (741–906), the first part is a long excerpt of the Royal Frankish Annals down to 813. From 814 onwards, however, the work is made up of eyewitness accounts, Paulus Diaconus and in relation to events in Lotharingia, the work of Adventius, Bishop of Metz.[3] In the later sections of book two, Regino discusses and deals with the various kings attempting to take power in Lotharingia, in particular criticising Zwentibald, the son of powerful magnate and later king Arnulf, Duke of Bavaria.[4] The chronological accuracy of the work has been questioned, however; Regino had adapted and changed Bede's Anno Mundi dating system to Anno Domini to reflect the works starting point of the Incarnation of Jesus.[5] The work is deemed important by modern scholars due to the fact it is the first chronicle to conventionally apply the AD dating system.[6]

Regino's chronicle is an important source on Bulgarian medieval history in that it is the only contemporary text hinting at the organisation of the Council of Preslav ("… [Boris I] gathered his entire empire and placed his younger son [Simeon I] as prince…").[citation needed]

Historians who made use of Regino's chronicle include Cosmas of Prague.[7]

The chronicle was first printed at Mainz in 1521.[citation needed]

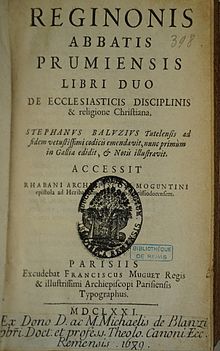

De ecclesiasticis disciplinis

[edit]

Regino also drew up, at the request of his friend and patron Radbod, Archbishop of Trier (d. 915), a collection of canons, Libri duo de synodalibus causis et disciplinis ecclesiasticis, dedicated to Hatto I, Archbishop of Mainz. It was a work on ecclesiastical discipline for use in ecclesiastical visitations. The work is divided into 434 sections. The title of the work in Migne's edition is Libellus DE ECCLESIASTICIS DISCIPLINIS ET RELIGIONE CHRISTIANA, COLLECTUS Ex jussu domini metropolitani Rathbodi Trevericae urbis episcopi, a Reginone quondam abbate Prumiensis monasterii, ex diversis sanctorum Patrum conciliis et decretis Romanorum pontificum. Substantial portions of this work were included in the Decretum Burchardi of 1012.

Section 364 (corresponding to Burchard 10.1) is the so-called Canon Episcopi (after its incipit Ut episcopi episcoporumque ministri omnibus viribus elaborare studeant) dealing with popular superstition.

Miscellaneous

[edit]Around 900, Regino lists four distinctive features of ethnicity: genus (origin, race), mores (customs, behavior), lingua (language), and leges (law). These categories would be considered key nominal qualifiers for ethnic identity from the Carolingian period onwards.[8]

References

[edit]- ^ ed. Edmond de Coussemaker, Scriptores de musica medii aevi, II (Paris, 1867), 1-73.

- ^ Stuart Airlie, "Sad stories of the death of kings": Narrative Patterns and Structures of Authority in Regino of Prum's Chronicle." in Narrative and History in the Early Medieval West, (eds) Elizabeth M. Tyler and Ross Balzaretti (Turnhout, 2006), p. 109.

- ^ West, Charles (2016). "Knowledge of the past and judgement of history in tenth century Trier: Regino of Prum and the lost manuscript of Bishop Adventius of Metz" (PDF). Early Medieval Europe. 24 (2): 143–147. doi:10.1111/emed.12138.

- ^ Maclean, Simon (2013). "Shadow Kingdom: Lotharingia and the Frankish World, c.850-c.1050". History Compass. 11 (6): 447–452. doi:10.1111/hic3.12049. hdl:10023/4176.

- ^ Simon Maclean, History and Politics in Late Carolingian and Ottonian Europe: the Chronicle of Regino of Prum and Adalbert of Magdeburg, (Manchester, 2009) pp. 20–22.

- ^ Maclean, Simon (2009). "Insinuation, Censorship and the Struggle for Late Carolingian Lotharingia in Regino of Prum's Chronicle". English Historical Review. 506: 6.

- ^ Marie Bláhová, "The Function of the Saints in Early Bohemian Historical Writing." In The Making of Christian Myths in the Periphery of Latin Christendom (ca 1000–1300), ed. Lars Boje Mortensen. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanums Forlag, 2006. p. 97.

- ^ Tor, D. G. (2017-10-20). The ʿAbbasid and Carolingian Empires: Comparative Studies in Civilizational Formation. BRILL. ISBN 9789004353046.

Sources

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Canon Law". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 193–203. (See p. 196.)

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Regino of Prüm". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Regino of Prüm". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.- Hubert Maximilian Ermisch, Die Chronik des Regino bis 813 (Göttingen, 1872)

- Paul Schulz, Die Glaubwürdigkeit des Abtes Regino van Prüm (Hamburg, 1894)

- Carl Josef Wawra, De Reginone Prumensis (Breslau, 1901)

- Auguste Molinier, Les Sources de l'histoire de France, Tome I (1901)

- Wilhelm Wattenbach, Deutschlands Geschichtsquellen, Band I (1904).

Editions and translations

[edit]- Chronicon:

- MacLean, Simon (ed. and tr.). History and politics in late Carolingian and Ottonian Europe. The chronicle of Regino of Prüm and Adalbert of Magdeburg. Manchester, 2009.

- Kurze, Friedrich (ed.). Reginonis abbatis Prumiensis Chronicon cum continuatione Treverensi. MGH SS rerum Germanicarum in usum scholarum separatim editi 50. Hanover, 1890. Available from the Digital MGH

- An earlier edition is in volume I of the Monumenta Germaniae historica Scriptores (1826).

- German translation (only 2.book): By Ernst Dümmler "Die Chronik des Abtes Regino von Prüm". Several editions, introduction dated twice, 1856 & 1889; 5. unveränderte Auflage (1939), at archive.org

- Tonarius

- Tonarius, ed. Edmond de Coussemaker, Scriptores de musica medii aevi. Vol. II. Paris, 1867. 1-73.

- De harmonica institutione, ed. Gerbert, Scriptores ecclesiastici de musica sacra. Vol. I. 1784.

- Libri duo de synodalibus causis et disciplines ecclesiasticis

- De synodalibus causis et disciplinis ecclesiasticis (in Latin). Paris: François Muguet. 1671.

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patrologia Latina, vol. 132, with analytical indexes

- Das Sendhandbuch des Regino von Prüm, ed. F. W. H. Wasserschleben and Wilfried Hartmann (Darmstad, 2004).

Further reading

[edit]- Airlie, Stuart (2006). "'Sad Stories of the death of kings': Narrative Patterns and Structures of Authority in Regino of Prum's Chronicle". In Tyler, Elizabeth M.; Balzaretti, Ross (eds.). Narrative and History in the Early Medieval West. Turnhout.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Maclean, Simon (February 2009). "Insinuation, Censorship and the Struggle for Late Carolingian Lotharingia in Regino of Prüm's Chronicle" (PDF). English Historical Review. 74.

- Maclean, Simon (2013). "Shadow Kingdom: Lotharingia and the Frankish World, c.850-c.1050". History Compass. 11 (6): 443–457. doi:10.1111/hic3.12049. hdl:10023/4176.

- West, Charles (2016). "Knowledge of the past and the judgement of history in tenth-century Trier: Regino of Prum and the lost manuscript of Bishop Adventius of Metz" (PDF). Early Medieval Europe. 24 (2): 137–159. doi:10.1111/emed.12138. Open access version

- “Ubaldo di Saint-Amand, Musica. Reginone di Prüm, Epistola de harmonica institutione”, Introduzione, traduzione e commento a cura di Alessandra Fiori, Firenze, Sismel - Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2011 (Società Internazionale per lo Studio del Medioevo Latino)

External links

[edit]- Reginon and music, musicologie.org (in French).

- Chartier, Yves. Reginon de Prüm: Epistola de Armonica Institutione. (in French). musicologie.org

- Hans Hubert Anton (1994). "Regino von Prüm". In Bautz, Traugott (ed.). Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German). Vol. 7. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 1483–1487. ISBN 3-88309-048-4.

- Digitized Edition of the Chronicon at E-codices.

- 9th-century births

- 915 deaths

- Chroniclers from the Holy Roman Empire

- 10th-century German historians

- German music theorists

- Tonaries

- Benedictine abbots

- Eifel in the Middle Ages

- 10th-century German writers

- 10th-century writers in Latin

- 10th-century jurists

- Canon law jurists

- 9th-century Christian abbots

- 10th-century Christian abbots